The Beginning of IBMA (1985-1986)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songwriter Mike O'reilly

Interviews with: Melissa Sherman Lynn Russwurm Mike O’Reilly, Are You A Bluegrass Songwriter? Volume 8 Issue 3 July 2014 www.bluegrasscanada.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS BMAC EXECUTIVE President’s Message 1 President Denis 705-776-7754 Chadbourn Editor’s Message 2 Vice Dave Porter 613-721-0535 Canadian Songwriters/US Bands 3 President Interview with Lynn Russworm 13 Secretary Leann Music on the East Coast by Jerry Murphy 16 Chadbourn Ode To Bill Monroe 17 Treasurer Rolly Aucoin 905-635-1818 Open Mike 18 Interview with Mike O’Reilly 19 Interview with Melissa Sherman 21 Songwriting Rant 24 Music “Biz” by Gary Hubbard 25 DIRECTORS Political Correctness Rant - Bob Cherry 26 R.I.P. John Renne 27 Elaine Bouchard (MOBS) Organizational Member Listing 29 Gord Devries 519-668-0418 Advertising Rates 30 Murray Hale 705-472-2217 Mike Kirley 519-613-4975 Sue Malcom 604-215-276 Wilson Moore 902-667-9629 Jerry Murphy 902-883-7189 Advertising Manager: BMAC has an immediate requirement for a volunteer to help us to contact and present advertising op- portunities to potential clients. The job would entail approximately 5 hours per month and would consist of compiling a list of potential clients from among the bluegrass community, such as event-producers, bluegrass businesses, music stores, radio stations, bluegrass bands, music manufacturers and other interested parties. You would then set up a systematic and organized methodology for making contact and presenting the BMAC program. Please contact Mike Kirley or Gord Devries if you are interested in becoming part of the team. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Call us or visit our website Martha white brand is due to the www.bluegrassmusic.ca. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Exploring the Bluegrass Nation As an Imagined Community

NOTIONS OF NATION: EXPLORING THE BLUEGRASS NATION AS AN IMAGINED COMMUNITY A Thesis by JORDAN L. LANEY Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2013 Department of Appalachian Studies NOTIONS OF NATIONS: EXPLORING THE BLUEGRASS NATION AS AN IMAGINED COMMUNITY A Thesis by JORDAN LANEY May 2013 APPROVED BY: Nancy S. Love Chairperson, Thesis Committee David Haney Member, Thesis Committee Fred Hay Member, Thesis Committee Patricia D. Beaver Director, Center for Appalachian Studies Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Cratis Williams Graduate School Copyright by Jordan L. Laney 2013 All Rights Reserved Abstract NOTIONS OF NATIONS: EXPLORING THE BLUEGRASS NATION AS AN IMAGINED COMMUNITY Jordan L. Laney B.F.A., Goddard College M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Nancy S. Love While bluegrass music has been a topic of conversation within the discipline of Appalachian Studies, research concerning the emergence of the community in cyberspace is relatively rare. Appalachian music’s role as a transnational facilitator is groundbreaking in areas of social networking, and as a member of the bluegrass community, I am fascinated by the communication that results now that members of that community can connect to friends in Europe, Japan, and France as easily as to next door neighbors. Noting that music is what brings these individuals together, this study addresses ways in which the bluegrass community embodies an imagined community and uses political language to gather in cyberspace. The study is not meant to discredit the direct ties the music has to Appalachia, but rather to applaud and understand the work of enthusiasts in the field who have found ways to mobilize the music through the Internet. -

A Biography of Doc Watson by Dan Miller Edited by Steve Carr

A Biography of Doc Watson by Dan Miller Edited by Steve Carr Introduction Over the past fifty years the guitar has had a very powerful influence on American music. Predominantly a rhythm instrument at the turn of the century, the guitar began to step out of the rhythm section in the 1930’s and 40’s and has maintained a dominant presence in every form of music from rock, to folk, to country, bluegrass, blues, and old- time. While Elvis, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, and other pop icons of the 50’s and 60’s certainly played a large role in bolstering the guitar’s popularity, the man who has had the deepest, most enduring, and most profound influence on the way the acoustic flat top guitar is played as a lead instrument in folk, old-time, and bluegrass music today is Arthel "Doc" Watson. To those of us who have spent hundreds of hours slowing down Doc Watson records in order to learn the tastefully selected notes that he plays and emulate the clear, crisp tone he pulls out of his instrument, Doc is a legend. However, Doc’s influence extends far beyond the small niche of guitar players who try to faithfully reproduce his guitar breaks because Doc Watson is not just a guitar player and singer - he is an American hero. To be recognized as a "national treasure" by President Jimmy Carter, honored with the National Medal of the Arts by President Bill Clinton, and given an honorary doctorate degree from the University of North Carolina calls for being more than a fine musician and entertainer. -

Jim Shumate and the Development of Bluegrass Fiddling

JIM SHUMATE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF BLUEGRASS FIDDLING A Thesis by NATALYA WEINSTEIN MILLER Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2018 Center for Appalachian Studies JIM SHUMATE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF BLUEGRASS FIDDLING A Thesis by NATALYA WEINSTEIN MILLER May 2018 APPROVED BY: Sandra L. Ballard Chairperson, Thesis Committee Gary R. Boye Member, Thesis Committee David H. Wood Member, Thesis Committee William R. Schumann Director, Center for Appalachian Studies Max C. Poole, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies Copyright by Natalya Weinstein Miller 2018 All Rights Reserved Abstract JIM SHUMATE AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF BLUEGRASS FIDDLING Natalya Weinstein Miller, B.A., University of Massachusetts M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Sandra L. Ballard Born and raised on Chestnut Mountain in Wilkes County, North Carolina, James “Jim” Shumate (1921-2013) was a pioneering bluegrass fiddler. His position at the inception of bluegrass places him as a significant yet understudied musician. Shumate was a stylistic co-creator of bluegrass fiddling, synthesizing a variety of existing styles into the developing genre during his time performing with some of the top names in bluegrass in the 1940s, including Bill Monroe in 1945 and Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs in 1948. While the "big bang" of bluegrass is considered to be in 1946, many elements of the bluegrass fiddle style were present in Bill Monroe's Blue Grass Boys prior to 1945. Jim Shumate’s innovative playing demonstrated characteristics of this emerging style, such as sliding double-stops (fingering notes on two strings at once) and syncopated, bluesy runs. -

The World Before Scruggs

THE WORLD BEFORE SCRUGGS "Try to imagine the world before Earl Scruggs -- it's unbelievable!" This exclamation by Rick was how our May, 1985 talks began, and it offers a keynote for his music and his thinking. To hear this makes you realize there's a lot more to Rick Shubb than "the guy who makes those capos." Still, one little invention has made Rick's name a musical household word: the ingenious and beauti- ful guitar (and banjo) capo known, simply, as the Shubb capo. Actually, Rick's other products include the innovative Shubb banjo fifth-string sliding capo, the Shubb compensated banjo bridge, the Shubb- Pearse steel (a distinctive bar for Dobro and steel guitar), a pickup and amplifier designed specifically for the banjo (no longer on the market). Most recently, his aptitude for computer database develop- ment has led him to produce a line of computer software for musicians.The first in this line is SongMaster, which will keep track of your songs, followed by GigMaster, a booking tool for musi- cians. Both are easy and affordable, and now available. But the guitar capo in particular has really put his name on the map. A Profile of Rick Shubb By Sandy Rothman Yet, Rick's part in the history of bluegrass in college towns like Berkeley, riding the and became aware of the Ramblers, music in California and the Bay Area long crest of the folk revival. With the forma- eventually taking one banjo lesson from preceded his emergence as a businessman tion of the Redwood Canyon Ramblers, a Neil Rosenberg. -

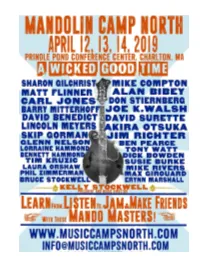

2019 Mandolin Camp North Program Guide

1 2 Table of Contents Page Welcome from Camp Director . 4 Camp's Mission Statement / Inviting Your Feedback . 5 Board of Directors / Volunteers. 5 Suggested Packing List . 6 Arrival at Camp: "I've just registered; Now What?" . 7 Camp Etiquette . 8 Audio / Video Recording of Classes and Concerts . .. 8 Did You Forget Something or Want to Stock Up on Snacks? . 8 Prindle Pond Conference Center . 9 Meals, Water, Coffee. 9 Emergency Contact Numbers. 9 Vendors . 10 Guests and Security . 10 Abbreviations and Skill Levels . 11 Jams . 12 Opportunities for Individual Attention . 12 ● “Find Your Level” . 12 ● Coaching Sessions . 12 Beginner Tracks . 13 Faculty Biographies . 13-17 Class Descriptions . 17-23 Other Events . 23 Prindle Pond Map . 24 The WiFi password is 0987654321 Prindle Pond Info/Emergency Info Prindle Pond’s office number is (508) 248-4737 Camp cell phone number is (203) 362-8807 3 Welcome Campers! 2019 is our 19th year at Music Camps North, our second camp as a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt nonprofit organization. Volunteers put this camp together, and we'll be relying on volunteers even more in the future. It's truly a labor of love. We view ourselves as a unique camp--our emphasis is on faculty's personal interaction with campers. You'll dine with faculty and find them available for advice throughout the weekend. Some faculty may even stay up late to jam with you. We've made some changes for the 2019 Camp: ● Me, the Music Director and President. In 2017 Phil Zimmerman let the Board of Directors know he wanted to lessen his Music Camps North duties. -

Bluegrass Unlimited Review

Bluegrass Unlimited review Deaton and Dream are a major amazement and ought to be in the running for discovery of the year. She has a rich, soulful voice with a very broad range — the kind of voice that could bring fresh air to Nashville, if that place had the sense to come calling and not try to bland her into pop diva-dom. Her vocals combine power and expressiveness, and she’s so gifted and experienced that she doesn’t succumb to the temptation to oversing anywhere. While most of the disc is straight bluegrass, some of it the driving kind, her most affecting moments arise, for me, on the slower, country-flavored material, which glows with the subtle passion and color of her voice. Off the evidence of this disc, she could probably make almost any kind of music scintillating. The set begins with "Loose Talk," an old country hit, done here at a ripping bluegrass clip, followed by some bluesy ’grass on "Better Man." At this point, the verdict is "real promise," and then she launches into the aching original love song "In Your Dreams," and the promise becomes fulfillment. Next, "You’re The One" nails it down — a complex modern bluegrass arrangement with a bowed bass introduction, fine fiddling, lead guitar, and mandolin behind a tour de force vocal, displaying Deaton’s full capacities. When the song, in the middle, slows way down to a gorgeous few lines of pure Deaton soul, you know you’ve come to some place special. The ensuing number, a heartbreaker about divorce, with quiet piano, mandolin, and fiddle and a nice harmony turn by guest Russell Moore, is absolutely captivating. -

2018-Bluegrass-Program.Pdf

Festival Grounds G C F A B C D E K H J I A Tent Seating E Main Lodge – Ice Cream, “The Living Room”, H Shower Building B Information Tent Merchandise Counter, and Rec Room I Gate House C Vendor Areas F The Loose Caboose J Dump Station D Main Stage G Workshop Tent K Family Activities We ask that everyone exercise care and caution while inside the park, as there are many children at play and pedestrians on the roads throughout. Things to Know WATER FILL UP LOCATIONS Main Grove Camp Sites #9-10, Outside Beachfront Restrooms, Behind Soda Machines, Back of Main Lodge, Shower Building by Street Light HOT Inside Coin-Operated SHOWERS & LAUNDRY ROOM In the Main Grove Camping Area Shower Building HANDICAPPED FRIENDLY FACILITIES Main Grove Restroom/Shower Building INSIDE FLUSH TOILETS & OUTSIDE RINSE OFF SHOWERS Restrooms located by the Beachfront and across from the Playground PORT-A-POTTIES located throughout the Park grounds FIRST AID and INFORMATION and LOST & FOUND at the Information Tent and in the Caboose CHARGING STATION available in the Main Lodge “Living Room” Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday MAIN LODGE— Festival Merch, Ice Cream, Living Room, Rec Hall LOOSE CABOOSE — Hot Dogs, Firedogs, Soups, and Snacks ICE & WOOD available at the Gate and Loose Caboose EMERGENCY PHONE #’s Park Office 207-725-6009 Police 207-725-5521 Ambulance 207-725-5541 Trash bags are provided at the Gate upon arrival. Additional bags are available in the Main Lodge. PLEASE PLACE YOUR TRASH BAGS AT THE ROADSIDES FOR DAILY PICK-UP. -

Various Banjo Jamboree Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Banjo Jamboree mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Banjo Jamboree Country: UK Style: Bluegrass MP3 version RAR size: 1396 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1990 mb WMA version RAR size: 1343 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 422 Other Formats: FLAC DTS ADX MP2 AIFF VOC TTA Tracklist Hide Credits A1 –Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs With The Foggy Mountain Boys* Foggy Mountain Breakdown 2:38 A2 –The Stanley Brothers And The Clinch Mountain Boys Tragic Love 2:21 A3 –Carl Story And His Ramblin' Mountaineers* Fire On The Banjo 2:08 A4 –Denver Duke & Jeffery Null* Rock And Roll Blues 2:37 A5 –Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs With The Foggy Mountain Boys* My Cabin In Caroline 2:34 Salty Dog Blues B1 –Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs* 2:30 Vocals – Benny Sims B2 –The Stanley Brothers And The Clinch Mountain Boys Blue Moon Of Kentucky 2:17 B3 –Carl Story And His Ramblin' Mountaineers* Banjolina 1:58 B4 –Denver Duke & Jeffery Null* All Washed Up With You 2:05 B5 –Carl Story And His Ramblin' Mountaineers* Banjo On The Mountain 1:52 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Five String Banjo SRW 16299, Mercury Wing, SRW 16299, Various Jamboree (LP, US 1965 SRW-16299-W Mercury Wing SRW-16299-W Comp) Five String Banjo Mercury Wing, MGW 12299 Various Jamboree (LP, MGW 12299 US 1965 Wing Records Comp, Mono) Five String Banjo SRW 16299, Mercury Wing, SRW 16299, Various Jamboree (LP, US 1965 SRW-16299-W Mercury Wing SRW-16299-W Comp) Related Music albums to Banjo Jamboree by Various Folk, World, & Country -

Peter Wernick

PETER WERNICK. Born 1946 Transcript of OH 1489V This interview was recorded on December 20, 2007, for the Maria Rogers Oral History Program. The interviewer is Anne Dyni. The interview also is available in video format, filmed by Liz McCutcheon. The interview was transcribed by Dee Baron. NOTE: The interviewer’s questions and comments appear in parentheses. Added material appears in brackets. ABSTRACT: Banjo player Pete Wernick talks about his career as a musician, ranging from playing bluegrass in New York City during the 1960s to playing banjo with Earl Scruggs on the David Letterman Show in 2005, as well as the many professional successes he has had in between, most notably as a member of the bluegrass band Hot Rize, which played together for twelve years and has continued to play highly popular reunion shows. [A]. 00:00 (Today is December 20th, 2007. I’m interviewing Pete Wernick of 7930 Oxford Road in Niwot. Pete, when and where were you born?) New York City, February 25, 1946. (Do you have any brothers or sisters?) My one and only sister just passed away about a month ago. (Oh, I’m sorry.) She was my older sister. Her name was Sarah and she lived in Boston. (Was she a musician?) Not at all. No. She was a writer and collaborated on various books including medical books. (Were there any instruments in your family at all?) My dad always had an interest in music and from his childhood he played harmonica by ear, and that was the one instrument he would take out at gatherings and so on and played on a pretty rudimentary level. -

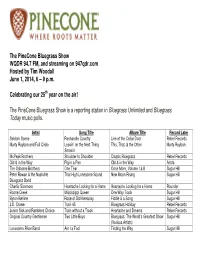

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Tim Woodall June 1, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Tim Woodall June 1, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Seldom Scene Panhandle Country Live at the Cellar Door Rebel Records Marty Raybon and Full Circle Leavin’ on the Next Thing This, That, & the Other Marty Raybon Smokin’ McPeak Brothers Shoulder to Shoulder Classic Bluegrass Rebel Records Old & in the Way Pig in a Pen Old & in the Way Arista The Osborne Brothers One Tear Once More, Volume I & II Sugar Hill Peter Rowan & the Nashville That High Lonesome Sound New Moon Rising Sugar Hill Bluegrass Band Charlie Sizemore Heartache Looking for a Home Heartache Looking for a Home Rounder Boone Creek Mississippi Queen One Way Track Sugar Hill Byron Berline Rose of Old Kentucky Fiddle & a Song Sugar Hill J.D. Crowe Train 45 Bluegrass Holiday Rebel Records Junior Sisk and Ramblers Choice Train without a Track Heartache and Dreams Rebel Records Original Country Gentlemen Two Little Boys Bluegrass: The World’s Greatest Show Sugar Hill (Various Artists) Lonesome River Band Am I a Fool Finding the Way Sugar Hill The Nashville Bluegrass Band The Ghost of Eli Renfrow The Boys are Back in Town Sugar Hill The Nashville Bluegrass Band Blackbirds and Crows Unleashed Sugar Hill James King Thirty Years of Farming Thirty Years of Farming Rounder Russell Johnson Waltz with Melissa A Picture from the Past New