Trademark Rights V. Freedom of Expression and Competition in Canada Daniel R. Bereskin, QC Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE TELEVISED SOUTH: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DOMINANT READINGS OF SELECT PRIME-TIME PROGRAMS FROM THE REGION By COLIN PATRICK KEARNEY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Colin P. Kearney To my family ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A Doctor of Philosophy signals another rite of passage in a career of educational learning. With that thought in mind, I must first thank the individuals who made this rite possible. Over the past 23 years, I have been most fortunate to be a student of the following teachers: Lori Hocker, Linda Franke, Dandridge Penick, Vickie Hickman, Amy Henson, Karen Hull, Sonya Cauley, Eileen Head, Anice Machado, Teresa Torrence, Rosemary Powell, Becky Hill, Nellie Reynolds, Mike Gibson, Jane Mortenson, Nancy Badertscher, Susan Harvey, Julie Lipscomb, Linda Wood, Kim Pollock, Elizabeth Hellmuth, Vicki Black, Jeff Melton, Daniel DeVier, Rusty Ford, Bryan Tolley, Jennifer Hall, Casey Wineman, Elaine Shanks, Paulette Morant, Cat Tobin, Brian Freeland, Cindy Jones, Lee McLaughlin, Phyllis Parker, Sue Seaman, Amanda Evans, David Smith, Greer Stene, Davina Copsy, Brian Baker, Laura Shull, Elizabeth Ramsey, Joann Blouin, Linda Fort, Judah Brownstein, Beth Lollis, Dennis Moore, Nathan Unroe, Bob Csongei, Troy Bogino, Christine Haynes, Rebecca Scales, Robert Sims, Ian Ward, Emily Watson-Adams, Marek Sojka, Paula Nadler, Marlene Cohen, Sheryl Friedley, James Gardner, Peter Becker, Rebecca Ericsson, -

Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature

Brown, Noel. " An Interview with Steve Segal." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 197–214. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-013>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 03:24 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 97 Chapter 13 A N INTERVIEW WITH STEVE SEGAL N o e l B r o w n Production histories of Toy Story tend to focus on ‘big names’ such as John Lasseter and Pete Docter. In this book, we also want to convey a sense of the animator’s place in the making of the fi lm and their perspective on what hap- pened, along with their professional journey leading up to that point. Steve Segal was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1949. He made his fi rst animated fi lms as a high school student before studying Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he continued to produce award- winning, independent ani- mated shorts. Aft er graduating, Segal opened a traditional animation studio in Richmond, making commercials and educational fi lms for ten years. Aft er completing the cult animated fi lm Futuropolis (1984), which he co- directed with Phil Trumbo, Segal moved to Hollywood and became interested in com- puter animation. -

Wonka Script V3

!1 Prologue: Wonka’s Factory (The actor playing Wonka enters the stage, he peers at the audience. CANDY KIDS carry high powered flash lights and illuminate WONKA as he invites the audience to enter a world of pure imagination. SONG: PURE IMAGAINATION !2 !3 SCENE 1: OUTSIDE THE BUCKET SHACK (WONKA narrates as children gather anticipating the arrival of the CANDY MAN) WONKA See these Kids? They meet outside Charlie’s house every day after lunch, with a shiny nickel apiece to buy a Wonka bar from the local Candy man. The only kid with no nickel is Charlie. ALL THE KIDS It’s the Candy Man! MATILDA What are you going to get? JAMEY (slurping a lollypop) Hey Charlie, help me pick something out. I got a nickel. MATILDA You’ve already got a lollipop. Shouldn’t you finish it first? JAMEY I can’t help it. I love candy! All candy! CHARLIE Stop it! You’re making my mouth water! SONG: THE CANDY MAN !4 !5 !6 !7 !8 !9 SCENE 2: THE BUCKET SHACK (Charlie’s grandparents are set on stage) MRS. BUCKET Charlie, come….eat. CHARLIE Here’s the paper, Dad. MR.BUCKET (looks at the front page) Well, I’ll be a chocolate crispy! Will you look at this? “Wonka factory to be opened to a lucky few.” GRANDMA JOSEPHINE Do you mean people are actually going to be allowed inside the factory? MRS. BUCKET Read what it says! GRANDMA GEORGINA “Mr. Willy Wonka has decided to allow five children to visit his factory. The lucky five will tour the factory and receive a lifetime supply of Wonka Chocolate.” GRANDPA JOE Tour the factory? CHARLIE A lifetime supply of chocolate? EVERYONE EXCEPT CHARLIE Read on! GRANDMA GEORGINA “Five golden tickets have been hidden among five million ordinary candy bars. -

Speech Sounds Vowels HOPE

This is the Cochlear™ promise to you. As the global leader in hearing solutions, Cochlear is dedicated to bringing the gift of sound to people all over the world. With our hearing solutions, Cochlear has reconnected over 250,000 cochlear implant and Baha® users to their families, friends and communities in more than 100 countries. Along with the industry’s largest investment in research and development, we continue to partner with leading international Speech Sounds:Vowels researchers and hearing professionals, ensuring that we are at the forefront in the science of hearing. A Guide for Parents and Professionals For the person with hearing loss receiving any one of the Cochlear hearing solutions, our commitment is that for the rest of your life in English and Spanish we will be here to support you Hear now. And always Ideas compiled by CASTLE staff, Department of Otolaryngology As your partner in hearing for life, Cochlear believes it is important that you understand University of North Carolina — Chapel Hill not only the benefits, but also the potential risks associated with any cochlear implant. You should talk to your hearing healthcare provider about who is a candidate for cochlear implantation. Before any cochlear implant surgery, it is important to talk to your doctor about CDC guidelines for pre-surgical vaccinations. Cochlear implants are contraindicated for patients with lesions of the auditory nerve, active ear infections or active disease of the middle ear. Cochlear implantation is a surgical procedure, and carries with it the risks typical for surgery. You may lose residual hearing in the implanted ear. -

How the Motion Picture Industry Miscalculates Box Office Receipts

How the motion picture industry miscalculates box office receipts S. Eric Anderson, Loma Linda University Stewart Albertson, Loma Linda University David Shavlik, Loma Linda University INTRODUCTION when movie grosses are adjusted for inflation, the Sound of Music was a more popular movie Box office grosses, once of interest only to than Titanic even though the box office gross movie industry executives, are now widely was over $400 million less. So why is it then publicized and immediately reported by movie that box office grosses are often the only industry tracking companies. The numbers reported, when the numbers have instantaneous tracking and reporting hurts little meaning? The motion picture industry, movies with weak openings, but helps movies aware that inflation helps movies grow bigger, with big openings become even bigger as has little interest in reporting highest grossing people flock to see what all the fuss is about. box office numbers with inflation-adjusted Due to inflation, the highest grossing movies dollars that will show the motion picture tend to be the more recent releases, which the industry is stagnant at best. They are able to motion picture industry is taking full get away with it since most don’t know how advantage of when promoting new movies. to handle those inflation-adjusting As a result, the motion picture industry has calculations. developed “highest grossing “ movie lists from almost every angle imaginable - opening Inflation-adjusted gross calculations are day, opening weekend, opening day non- inaccurate weekend, opening day during the fall, winter and spring, opening day Memorial weekend, Some tracking companies have begun second weekend of release, fewest screens, reporting box office grosses with the less etc. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

2019-BENNY-AND-JOON.Pdf

CREATIVE TEAM KIRSTEN GUENTHER (Book) is the recipient of a Richard Rodgers Award, Rockefeller Grant, Dramatists Guild Fellowship, and a Lincoln Center Honorarium. Current projects include Universal’s Heart and Souls, Measure of Success (Amanda Lipitz Productions), Mrs. Sharp (Richard Rodgers Award workshop; Playwrights Horizons, starring Jane Krakowski, dir. Michael Greif), and writing a new book to Paramount’s Roman Holiday. She wrote the book and lyrics for Little Miss Fix-it (as seen on NBC), among others. Previously, Kirsten lived in Paris, where she worked as a Paris correspondent (usatoday.com). MFA, NYU Graduate Musical Theatre Writing Program. ASCAP and Dramatists Guild. For my brother, Travis. NOLAN GASSER (Music) is a critically acclaimed composer, pianist, and musicologist—notably, the architect of Pandora Radio’s Music Genome Project. He holds a PhD in Musicology from Stanford University. His original compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, among others. Theatrical projects include the musicals Benny & Joon and Start Me Up and the opera The Secret Garden. His book, Why You Like It: The Science and Culture of Musical Taste (Macmillan), will be released on April 30, 2019, followed by his rock/world CD Border Crossing in June 2019. His TEDx Talk, “Empowering Your Musical Taste,” is available on YouTube. MINDI DICKSTEIN (Lyrics) wrote the lyrics for the Broadway musical Little Women (MTI; Ghostlight/Sh-k-boom). Benny & Joon, based on the MGM film, was a NAMT selection (2016) and had its world premiere at The Old Globe (2017). Mindi’s work has been commissioned, produced, and developed widely, including by Disney (Toy Story: The Musical), Second Stage (Snow in August), Playwrights Horizons (Steinberg Commission), ASCAP Workshop, and Lincoln Center (“Hear and Now: Contemporary Lyricists”). -

Dukes of Hazzard 7

Dukes of hazzard 7 click here to download This is my Tribute to the greatest TV serie. The Dukes Of Hazzard with the amazing cast: Denver Pyle as Uncle. While driving through Osage, the most feared county around ruled by the mean Colonel Claiborne, Bo and. This is a list of episodes for the CBS action-adventure/comedy series The Dukes of Hazzard. The show ran for seven seasons and a total of episodes. Many of the episodes followed a similar structure: "out-of-town crooks pull a robbery, Duke boys blamed, spend the rest of the hour clearing their names, the Episodes · Season 2 (–80) · Season 3 (–81) · Season 4 (–82). Action · Bo and Luke are hired to haul what they think is a shipment of shock absorbers. Actually, they've been duped into driving a rolling casino. www.doorway.ru: The Dukes of Hazzard: Season 7: Paul R. Picard, Tom Wopat, John Schneider, Catherine Bach, Denver Pyle, Sonny Shroyer, Ben Jones, James Best, Sorrell Booke, Waylon Jennings: Movies & TV. Preview and download your favorite episodes of The Dukes of Hazzard, Season 7, or the entire season. Buy the season for $ Episodes start at $ The Dukes of Hazzard Season 7. Get ready for the action - Hazzard County style - as Luke and Bo Duke and their beautiful cousin Daisy Duke push the good fight just a little more than the law will allow. With a knack for getting into trouble there's racing cars, flying cars, tumbling cars and plenty of good old-fashioned country. The seventh and final season of Dukes of Hazzard finds the familiar cast back in harness, with the exception of Don Pedro Colley in the recurring role of Chickasaw County Sheriff Ed Little. -

Dodge Hemi Diecast Toys and Diecast Scale Model Cars

dodge hemi diecast toys and diecast scale model cars Toy Wonders diecast scale model cars Catalog of dodge hemi diecast for wholesalers and retailers only dodge hemi diecast Created on 8/23/2009 Products found: 13 ERTL JoyRide - The Dukes of Hazzard General Lee Dodge Charger (1969, 1:18, Orange) 32485 Item# 32485OR Greenlight Auction Block - Barrett Jackson Series 6 (1:64, Asstd.) 21645/48 Item# 21645/48 Greenlight Auction Block - Series 5 (1:64, Asstd.) 21635/48 Item# 21635/48 Greenlight Black Bandit Series 2 (1:64, Asstd.) 27620/48 Item# 27620/48 Greenlight Factory 2 Pack - Series 1 (1:64, Asstd.) 24610 Item# 24610 Greenlight Muscle Car Garage - Dodge Challenger Convertible (1970, 1:18, Orange) 50811 Item# 50811OR Greenlight Muscle Car Garage - Dodge Challenger Convertible (1970, 1:18, Plum Crazy) 50810 Item# 50810PR http://www.toywonders.com/productcart/pc/showsearchr...withStock=-1&resultCnt=25&keyword=dodge+hemi+diecast (1 of 2) [8/23/2009 7:57:57 AM] dodge hemi diecast toys and diecast scale model cars RC2 ERTL Authentics - Dodge Charger (1966, 1:18, Light Purple) 33933 Item# 33933PR RC2 ERTL Authentics Chase Car - Dodge Charger Super Bee Hard Top (1971, 1:18, Red) CC39498 Item# CC39498 RC2 ERTL Elite - Plymouth Superbird Hard Top (1970, 1:18, Blue) 39399 Item# 39399BU RC2 ERTL Elite Chase Car - Dodge Charger R/T Hard Top (1970, 1:18, Orange) CC39314 Item# CC39314 RC2 ERTL JoyRide - The Dukes of Hazzard Dodge Charger Hard Top (1969, 1:25, Orange) 7967DO Item# 7967DO RC2 ERTL Mopar - Dodge Daytona Race Car #3 Don White (1969, 1:18, -

Tv Pg 01-04-11.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, January 4, 2011 7 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening January 4, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC No Ordinary Family V Detroit 1-8-7 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS Live to Dance NCIS Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX Glee Million Dollar Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E The First 48 The First 48 The First 48 The First 48 Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC Demolition Man Demolition Man Crocodile Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather When Animals Strike When Animals Strike When Animals Strike When Animals Strike Animals Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET American Gangster The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show State 2 Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Matchmaker Matchmaker The Fashion Show Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local The Dukes of Hazzard The Dukes of Hazzard Canadian Bacon 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY 29 CNBC 57 Disney Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Daily Colbert Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Futurama Local 9 NBC-KUSA 37 USA 65 We DISC Local Local Dirty Jobs -

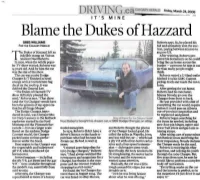

Blame the Dukes of Hazzard GREG WILLIAMS Roberts Says

DRIVING;Ca CALGARY HERALD Fnday. March 24,2006 IT'S MINE Blame the Dukes of Hazzard GREG WILLIAMS Roberts says. So, he placed his FOR THE CALGARY HERALD bid and ultimately won the auc- tion, paying between $12,000 to 'he Dukes of Hazzard left an $13,000 US. indelible stamp on Vulcan After winning, Roberts pre- Tresident Neel Roberts. pared his documents so he could In 1979, when the wildly popu- bring the car home across the lar TV show started, Roberts was border — a process he says is eas- 14 years old. And for him the car ier than many people might was the star of the show. think. The car was a 1969 Dodge Roberts rented a U-Haul trailer Charger R/T finished in hemi hitched it to his CMC Canyon orange with a Confederate flag pickup truck and made the run to decal on the rooftop. It was Iowa. dubbed the General Lee. After getting the car home, "The Dukes of Hazzard TV Roberts had his mechanic, show definitely planted the Manny Noualy, go over the seed," Roberts says. "That show Charger from front to back. (and the '69 Charger) would have He was provided with a list of been the genesis of my apprecia- everything the car would require tion for all things Mopar." before it could pass an Alberta The Dodge Charger, intro- out-of-province inspection and duced in 1966, was Chrysler Mo- be registered and plated. tor Corp.'s answer to the fastback Greg Williams for the Calgary Herald Roberts began searching for explosion started by the Ford Neel Roberts bought his dream car, a 1969 Dodge Charger, on eBay. -

Notice of Opposition Opposer Information Applicant Information

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA697851 Filing date: 09/23/2015 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation Granted to Date 09/23/2015 of previous ex- tension Address 10201 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 UNITED STATES Attorney informa- David M. Kelly tion Kelly IP, LLP 1919 M Street, N.W. Suite 610 Washington, DC 20036 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Applicant Information Application No 86325966 Publication date 05/26/2015 Opposition Filing 09/23/2015 Opposition Peri- 09/23/2015 Date od Ends International Re- NONE International Re- NONE gistration No. gistration Date Applicant Allied Domecq Spirits & Wine Limited 72 Chancellors Road London, W69RS UNITED KINGDOM Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 033. First Use: 0 First Use In Commerce: 0 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Alcoholic beverages except beers, namely, wines; spirits; liqueurs Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act section 2(d) Dilution Trademark Act section 43(c) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. Registration 4566718 Application Date 06/05/2013 No. Registration Date 07/15/2014 Foreign Priority NONE Date Word Mark DUFF Design Mark Description of NONE Mark Goods/Services Class 032. First use: First Use: 2013/06/01 First Use In Commerce: 2013/06/01 Beers U.S.