Streaming Live from the Playroom! Media Identity, Design and Trojan Horses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playstation®4 Launches Across the United States

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PLAYSTATION®4 LAUNCHES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA With the PS4™system, Sony Computer Entertainment Welcomes Gamers to a New Era of Rich, Immersive Gameplay Experiences TOKYO, November 15, 2013 – Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (SCEI) today launched PlayStation®4 (PS4™), a system built for gamers and inspired by developers. The PS4 system is now available in the United States and Canada at a suggested retail price of USD $399 and CAD $399, arriving with a lineup of over 20 first- and third-party games, including exclusive titles like Knack™ and Killzone: Shadow Fall™. In total, the PS4 system will have a library of over 30 games by the end of the year. *1 “Today’s launch of PS4 represents a milestone for all of us at PlayStation, our partners in the industry, and, most importantly, all of the PlayStation fans who live and breathe gaming every day,” said Andrew House, President and Group CEO, Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. “With unprecedented power, deep social capabilities, and unique second screen features, PS4 demonstrates our unwavering commitment to delivering phenomenal play experiences that will shape the world of games for years to come.” The PS4 system enables game developers to realize their creative vision on a platform specifically tuned to their needs, making it easier to build huge, interactive worlds in smooth 1080p HD resolution.*2 Its supercharged PC architecture – including an enhanced Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) and 8GB of GDDR5 unified system memory – is designed to ease game creation and deliver a dramatic increase in the richness of content available on the platform. -

Twitch and Professional Gaming: Playing Video Games As a Career?

Twitch and professional gaming: Playing video games as a career? Teo Ottelin Bachelor’s Thesis May 2015 Degree Programme in Music and Media Management Business and Services Management Description Author(s) Type of publication Date Ottelin, Teo Joonas Bachelor´s Thesis 08052015 Pages Language 41 English Permission for web publication ( X ) Title Twitch and professional gaming: Playing video games as a career? Degree Programme Degree Programme in Music and Media Management Tutor(s) Hyvärinen, Aimo Assigned by Suomen Elektronisen Urheilun Liitto, SEUL Abstract Streaming is a new trend in the world of video gaming that can make the dream of many video gamer become reality: making money by playing games. Streaming makes it possible to broadcast gameplay in real-time for everyone to see and comment on. Twitch.tv is the largest video game streaming service in the world and the service has over 20 million monthly visitors. In 2011, Twitch launched Twitch Partner Program that gives the popular streamers a chance to earn salary from the service. This research described the world and history of video game streaming and what it takes to become part of Twitch Partner Program. All the steps from creating, maintaining and evolving a Twitch channel were carefully explored in the two-month-long practical research process. For this practical research, a Twitch channel was created from the beginning and the author recorded all the results. A case study approach was chosen to demonstrate all the challenges that the new streamers would face and how much work must be done before applying for Twitch Partner Program becomes a possibility. -

Ps4 Download Destiny 2 in Rest Mode How to Update Disney Plus App on PS4

ps4 download destiny 2 in rest mode How To Update Disney Plus App On PS4. With Disney Plus doing so well across the globe, one question that a few folks have is ‘ how to update Disney Plus app on PS4 ‘? Well, we’ve got just the answer to that query right here. Without further ado! How To Update Disney Plus App On PS4. Keeping your Disney Plus PS4 app up to date is essential as it allows you to be sure that you’ve got the latest version of the app. This means that in addition to any bug fixes or quality of life changes that Disney may make to the app, you’ll also benefit from any extra features that they add too. So this is how to update Disney Plus app on PS4. Updating the Disney Plus app on PS4 costs absolutely nothing and it’s super simple to do if you follow the steps below: Updating Disney Plus App On PS4. Turn on your PS4 or awaken it from Rest Mode Log in with your chosen PlayStation profile Highlight the Disney Plus App Press the Options button on your DualShock 4 controller A menu should appear on the right side of the screen Scroll down and highlight ‘Check for Update’ Press the X button on the DualShock 4 controller The PS4 will then check the PlayStation Network to see if a new version of the Disney Plus PS4 app exists If it does it will begin downloading it and will inform you once the download has been complete If there are no new updates, you’ll see the text “the installed application is the latest version” One really handy feature is being able to see what fixes, tweaks and new features have been added in the latest version of the Disney Plus PS4 app. -

Weigel Colostate 0053N 16148.Pdf (853.6Kb)

THESIS ONLINE SPACES: TECHNOLOGICAL, INSTITUTIONAL, AND SOCIAL PRACTICES THAT FOSTER CONNECTIONS THROUGH INSTAGRAM AND TWITCH Submitted by Taylor Weigel Department of Communication Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2020 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Evan Elkins Greg Dickinson Rosa Martey Copyright by Taylor Laureen Weigel All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ONLINE SPACES: TECHNOLOGICAL, INSTITUTIONAL, AND SOCIAL PRACTICES THAT FOSTER CONNECTIONS THROUGH INSTAGRAM AND TWITCH We are living in an increasingly digital world.1 In the past, critical scholars have focused on the inequality of access and unequal relationships between the elite, who controlled the media, and the masses, whose limited agency only allowed for alternate meanings of dominant discourse and media.2 With the rise of social networking services (SNSs) and user-generated content (UGC), critical work has shifted from relationships between the elite and the masses to questions of infrastructure, online governance, technological affordances, and cultural values and practices instilled in computer mediated communication (CMC).3 This thesis focuses specifically on technological and institutional practices of Instagram and Twitch and the social practices of users in these online spaces, using two case studies to explore the production of connection- oriented spaces through Instagram Stories and Twitch streams, which I argue are phenomenologically live media texts. In the following chapters, I answer two research questions. First, I explore the question, “Are Instagram Stories and Twitch streams fostering connections between users through institutional and technological practices of phenomenologically live texts?” and second, “If they 1 “We” in this case refers to privileged individuals from successful post-industrial societies. -

Universidad Nacional De Rosario Facultad De Humanidades Y Artes Escuela De Música

Universidad Nacional de Rosario Facultad de Humanidades y Artes Escuela de Música “El sonido y la música en los videojuegos de la década de 2010” Informe final de Seminario de Investigación Trabajo final de Licenciatura Autores: Ignacio Terré y Giuliano Zampa Profesor / Tutor: Federico Buján 2020 1 ÍNDICE Introducción……………………………………………………...……….3 I- Breve reseña acerca de la relación música-videojuegos y su desarrollo histórico………………………………………………..7 II- Los nuevos Paradigmas de la Música Diegética y Extradiegética en el ámbito de los videojuegos…….……..22 III- La dinámica rítmica en los videojuegos…...………..…….….33 IV- Simulación musical………………………….…………………..42 V- Blind Legend: una aventura sonora.…………………...…......62 Conclusiones……………………………………………………………75 Bibliografía………………………………………………………………78 Webgrafía………………………………………………………………..80 Ludografía……………………………………………………………….82 2 Introducción “Mike Pummel lo resume brevemente: el juego no sabe dónde está la música y la música no sabe dónde está el juego” (Belinkie, 1999) En el siguiente trabajo indagaremos acerca del que para nosotros es uno de los campos contemporáneos más prolíficos en la utilización de la música y el sonido: el videojuego. Es indudable que la música juega un rol importante en los diversos medios audiovisuales como multimediales, y los videojuegos han pasado de ser una actividad de nicho en sus orígenes a ser fenómenos de gran alcance social (como el Pokémon Go en 2016). Un importante reconocimiento a la música de videojuegos ocurrió en el festejo número 55 de los Grammys en 2012. La obra ganadora de la categoría Best score soundtrack of visual media fue el soundtrack de Journey, sacado al mercado ese mismo año. Compuesto por Austin Wintory, compositor de los otros videojuegos como Flow y Flower, con tan solo 28 años estuvo compartiendo la nominación con reconocidos compositores tales como Hans Zimmer para The Dark Knight Rises y John Williams con Adventures of Tintin. -

Playstation App for Mac

Playstation App For Mac 1 / 4 Playstation App For Mac 2 / 4 You can also stream a wide range of PlayStation games with a PS Now subscription on a PC.. Download Playstation App For MacPlaystation Remote App For MacPlaystation App For MacPlaystation App For MacQuick NavigationThe Remote Play app for PC and Mac lets you stream games from your PS4 to your laptop or desktop computer.. Even if you don’t have your PS4’s control, you can use a phone or a tablet as a controller. 1. playstation store 2. playstation 4 3. playstation support Please Note: PS Now does not support Macintosh computers at this time Download the PS Now app, connect a controller and start streaming hundreds of games on demand.. If any of these is your requirement, you should get the PS4 Second Screen right away.. 4 FAQsThis is the tutorial to download PS4 Second Screen PC on Windows 10 and macOS-powered computers.. I wish they release it soon, I don't really like switching to bootcamp for an hour just to play the games. playstation store playstation store, playstation 4, playstation 5, playstation network, playstation, playstation support, playstation 2, playstation login, playstation 1, playstation now, playstation 3 Asian Riddles Free Download PS4 Second Screen also allows adding text or writing in any text area using the connected device. Avervision Cp135 Software download free software Episode 6.5 User Guide For Mac playstation 4 Pengolahan Limbah Stream the entire PS Now game collection to your Windows PC – more than 700 games, on.. My brand new Macbook Pro with 8GB of RAM was running the fan like crazy and couldn't even keep websites loaded. -

Twitchtv Strategic Analysis

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Spring 2021 TwitchTV Strategic Analysis Carter Matt University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Other Education Commons Matt, Carter, "TwitchTV Strategic Analysis" (2021). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 297. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/297 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TwitchTV Strategic Analysis An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln By Carter Matt Bachelor of Science in Business Administration Marketing College of Business April 18, 2021 Faculty Mentor: Marijane England, Ph.D., Management ABSTRACT TwitchTV is a livestreaming platform that exists within the livestream community industry. It connects content creators known as streamers with viewers that can engage with the streamer and community via chat. This report seeks to provide an analysis of TwitchTV’s current position within this industry and provide recommendations for further developing its platform. It also seeks to analyze trends in the industry and environment that may affect TwitchTV in the short and long term. Specific tools utilized to analyze these trends and growth opportunities include a Porter’s Five Forces analysis, PESTEL analysis, and SWOT analysis. -

Plantas Vs Zombies

OPINION EN MODO HARDCORE AGOSTO 2014 TodoEl presenteJuegos de Chile en el desarrollo de videojuegos Especial: La historia de Shin Megami Tensei The Last of Us salta a la nueva generación GuerraPLANTAS VS ZOMBIES en tu jardín |UNA REALIZACION DE PLAYADICTOS| 03 TodoJuegos Destacados THE LAST OF US El salto a PlayStation 4 del mejor 4 juego de la generación anterior. ZONA RETRO Un vistazo a la Atari 2600, 22 la primera gran consola. ULTIMATE TEAM 14 HOMOSEXUALIDAD Un tema controvertido que no ha 26 estado ajeno a los videojuegos. TERROR SERIE B Revisa cómo los desarrolladores 32 indie rescataron el survival horror. GARDEN WARFARE Uno de los éxitos del año en la 36 Xbox One llega a PlayStation. DEBATE ¿Vale la pena saltar ahora a la 44 nueva generación de consolas? KING OF FIGHTERS 46 SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI Un viaje hacia el universo de esta 52 oscura saga con sello japonés. HECHO EN CHILE El presidente de VG Chile hace 60 un balance de la industria criolla. TOP TEN Los diez mejores personajes 68 femeninos en los videojuegos. LOGROS Y TROFEOS ¿Un mal necesario? Un repaso a J-STARS VICTORY VS 70 78 los orígenes de estos incentivos. CROWDFUNDING El financiamiento colectivo 94 se abre camino en la industria. CÓDIGO MUERTO El eterno debate sobre la forma 100 en que clasificamos a los juegos. NOVEDADES Metro Redux, Diablo III y 104 Tales of Xillia 2 destacan este mes. FESTIGAME SHIGERU MIYAMOTO 86 La feria chilena de videojuegos 114 se alista para una nueva edición. 02 TodoJuegos Es la número 4.. -

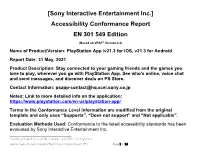

Accessibility Conformance Report Playstation

[Sony Interactive Entertainment Inc.] Accessibility Conformance Report EN 301 549 Edition (Based on VPAT® Version 2.4) Name of Product/Version: PlayStation App /v21.3 for iOS, v21.3 for Android Report Date: 31 May, 2021 Product Description: Stay connected to your gaming friends and the games you love to play, wherever you go with PlayStation App. See who's online, voice chat and send messages, and discover deals on PS Store. Contact Information: [email protected] Notes: Link to more detailed info on the application: https://www.playstation.com/en-us/playstation-app/ Terms in the Conformance Level information are modified from the original template and only uses “Supports”, “Does not support” and “Not applicable”. Evaluation Methods Used: Conformance to the listed accessibility standards has been evaluated by Sony Interactive Entertainment Inc. __________________________________ “Voluntary Product Accessibility Template” and “VPAT” are registered service marks of the Information Technology Industry Council (ITI) Page 1 of 24 Applicable Standards/Guidelines This report covers the degree of conformance for the following accessibility standard/guidelines: Standard/Guideline Included In Report Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 Level A (Yes) Level AA (Yes) Level AAA (No) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 Level A (Yes) Level AA (Yes) Level AAA (No) EN 301 549 Accessibility requirements suitable for public procurement of ICT (Yes) products and services in Europe, - V3.1.1 (2019-11) Terms The terms used in the Conformance Level information are defined as follows: Supports: All assessed screens have successfully passed the assessment and are compliant with the criterion. -

Download Ps4 Game from Phone How to Download Games to PS4 from Your Smartphone OR PC

download ps4 game from phone How to Download Games to PS4 from your Smartphone OR PC. Let’s have a look at a method to Download Games to PS4 from Your Smartphone or PC using the app and converting the downloaded games to one that will run in PS4. So have a look at complete guide discussed below to proceed. [dropcap]G[/dropcap]ames are the best aspects of the digital life, half of the world is indulged in the gaming sections. PS4 is the well-known gaming console which is greatly popular among the people and they love to enjoy several games available for it. Every time the new game is launched for the PS4 the people find the easiest way to grab it, they tend to resist the only option for buying the game disc for the console. Actually, there is a number of ways to get the games to PS4, these could be easily downloaded to PS4 from phone or PC. This is what most of the users would be confused about, certainly, this is easy to do and even many of the games could be grasped for the PS4 right using this method. The issue is that the method is not clearly known to the users for downloading the games to PS4 from phone or PC. We have written almost everything to introduce you and make the clear view about the topic of this post, now we are to share you with the exact method of downloading the games to the PS4 right from phone or PC. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College An

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF TWITCH STREAMERS: NEGOTIATING PROFESSIONALISM IN NEW MEDIA CONTENT CREATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CHRISTOPHER M. BINGHAM Norman, Oklahoma 2017 AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF TWITCH STREAMERS: NEGOTIATING PROFESSIONALISM IN NEW MEDIA CONTENT CREATION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION BY _______________________________ Dr. Eric Kramer, Chair _______________________________ Dr. Ralph Beliveau _______________________________ Dr. Ioana Cionea _______________________________ Dr. Lindsey Meeks _______________________________ Dr. Sean O’Neill Copyright by CHRISTOPHER M. BINGHAM 2017 All Rights Reserved. Dedication For Gram and JJ Acknowledgements There are many people I would like to acknowledge for their help and support in finishing my educational journey. I certainly could not have completed this research without the greater Twitch community and its welcoming and open atmosphere. More than anyone else I would like to thank the professional streamers who took time out of their schedules to be interviewed for this dissertation, specifically Trainsy, FuturemanGaming, Wyvern_Slayr, Smokaloke, MrLlamaSC, BouseFeenux, Mogee, Spooleo, HeavensLast. and SnarfyBobo. I sincerely appreciate your time, and am eternally envious of your enthusiasm and energy. Furthermore I would like to acknowledge Ezekiel_III, whose channel demonstrated for me the importance of this type of research to semiotic theory, as well as CohhCarnage and ItmeJP, whose show Dropped Frames, allowed further insight into the social milieu of professional Twitch streaming. I thank Drew Harry, PhD, Twitch’s Director of Science for responding to my enquiries. Finally, I thank all the streamers and fans who attended TwitchCon in 2015 and 2016, for the wonderful experience. -

Daniela Rangel Granja Indústria Dos Jogos Eletrônicos: a Evolução Do Valor Da Informação E a Mais-Valia

DANIELA RANGEL GRANJA INDÚSTRIA DOS JOGOS ELETRÔNICOS: A EVOLUÇÃO DO VALOR DA INFORMAÇÃO E A MAIS-VALIA 2.0 Dissertação de mestrado Setembro de 2015 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE INFORMAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIA DA INFORMAÇÃO DANIELA RANGEL GRANJA INDÚSTRIA DOS JOGOS ELETRÔNICOS: A EVOLUÇÃO DO VALOR DA INFORMAÇÃO E A MAIS-VALIA 2.0 Rio de Janeiro 2015 DANIELA RANGEL GRANJA INDÚSTRIA DOS JOGOS ELETRÔNICOS: A EVOLUÇÃO DO VALOR DA INFORMAÇÃO E A MAIS-VALIA 2.0 Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação, Convênio entre o Instituto Brasileiro de Informação em Ciência e Tecnologia e a Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/Escola de Comunicação, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciência da Informação. Orientador: Marcos Dantas Loureiro Rio de Janeiro 2015 CIP - Catalogação na Publicação Granja, Daniela Rangel G759 i Indústria dos jogos eletrônicos: a evolução do valor da informação e a mais-valia 2.0 / Daniela Rangel Granja. -- Rio de Janeiro, 2015. 149 f. Orientador: Marcos Dantas Loureiro. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Escola da Comunicação, Instituto Brasileiro de Informação em Ciência e Tecnologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação, 2015. 1. Jogos eletrônicos-Indústria. 2. Valor da Informação. 3. Capital-Informação. 4. Mais-valia 2.0. 5. Jardins murados. I. Loureiro, Marcos Dantas, orient. II. Título. Elaborado pelo Sistema de Geração Automática da UFRJ com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a). DANIELA RANGEL GRANJA INDÚSTRIA DOS JOGOS ELETRÔNICOS: A EVOLUÇÃO DO VALOR DA INFORMAÇÃO E A MAIS-VALIA 2.0 Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação, Convênio Instituto Brasileiro de Informação em Ciência e Tecnologia e Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/Escola de Comunicação, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciência da Informação.