Conservation Plan for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Pinaroo Ramsar Site

Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Disclaimer The Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW (DECC) has compiled the Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. DECC does not accept responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information supplied by third parties. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Readers should seek appropriate advice about the suitability of the information to their needs. © State of New South Wales and Department of Environment and Climate Change DECC is pleased to allow the reproduction of material from this publication on the condition that the source, publisher and authorship are appropriately acknowledged. Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney PO Box A290, Sydney South 1232 Phone: 131555 (NSW only – publications and information requests) (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au DECC 2008/275 ISBN 978 1 74122 839 7 June 2008 Printed on environmentally sustainable paper Cover photos Inset upper: Lake Pinaroo in flood, 1976 (DECC) Aerial: Lake Pinaroo in flood, March 1976 (DECC) Inset lower left: Blue-billed duck (R. Kingsford) Inset lower middle: Red-necked avocet (C. Herbert) Inset lower right: Red-capped plover (C. Herbert) Summary An ecological character description has been defined as ‘the combination of the ecosystem components, processes, benefits and services that characterise a wetland at a given point in time’. -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Royal Historical Society of Victoria 19 Queen Street

ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA 19 QUEEN STREET. MELBOURNE. C.l 62 7052 15 Kett St., Nunawading, 878 7720 3 December 1966 Rev. Gerard Tucker, Brotherhood of St.Lawrence, LARA. Dear Sir, I am advised that you are a direct descendant of Rev.Horace Finn Tucker, sometime of ^.Christ Church, South Yarra, author of The Hew Arcadia, and founder of the tucker village Settlements. As an historian I have been interested for some years in his work. In 1964 a series of articles I had written on the Tucker settlements of thd nineties appeared in the Educational Magazine. More recently I have dealt with the general subject of village settlements in an address to the Royal Historical Society of Victoria( a list of settlements isssued by me on that occasion is enclos ed for your interest). Since reading The Hew Arcadia I realize how little T know of the social movements and idealism of the Utopians of the nineties. Some clues to the way men were thinking then may be included in the other writings-if any-of H.F.Tucker or in biographical details xbbl relating to him. Have you any such material that could be borrowed, perused and returned? I have gleaned from Christ Church all possible in the Church journals but still do not know such elementary details as date of birth and death, education, travels, friends, interests etc of Rev. H.F.Tucker. Believe me this is not idle prying- for the man's social experiments and writings belong to history. I knew, of course, of the Brotherhood's village settlement at Carrum Bbossh Downs, but not till recently, did your address come my way and the possible connexion pointed out. -

Taylors Hill-Werribee South Sunbury-Gisborne Hurstbridge-Lilydale Wandin East-Cockatoo Pakenham-Mornington South West

TAYLORS HILL-WERRIBEE SOUTH SUNBURY-GISBORNE HURSTBRIDGE-LILYDALE WANDIN EAST-COCKATOO PAKENHAM-MORNINGTON SOUTH WEST Metro/Country Postcode Suburb Metro 3200 Frankston North Metro 3201 Carrum Downs Metro 3202 Heatherton Metro 3204 Bentleigh, McKinnon, Ormond Metro 3205 South Melbourne Metro 3206 Albert Park, Middle Park Metro 3207 Port Melbourne Country 3211 LiQle River Country 3212 Avalon, Lara, Point Wilson Country 3214 Corio, Norlane, North Shore Country 3215 Bell Park, Bell Post Hill, Drumcondra, Hamlyn Heights, North Geelong, Rippleside Country 3216 Belmont, Freshwater Creek, Grovedale, Highton, Marhsall, Mt Dunede, Wandana Heights, Waurn Ponds Country 3217 Deakin University - Geelong Country 3218 Geelong West, Herne Hill, Manifold Heights Country 3219 Breakwater, East Geelong, Newcomb, St Albans Park, Thomson, Whington Country 3220 Geelong, Newtown, South Geelong Anakie, Barrabool, Batesford, Bellarine, Ceres, Fyansford, Geelong MC, Gnarwarry, Grey River, KenneQ River, Lovely Banks, Moolap, Moorabool, Murgheboluc, Seperaon Creek, Country 3221 Staughtonvale, Stone Haven, Sugarloaf, Wallington, Wongarra, Wye River Country 3222 Clilon Springs, Curlewis, Drysdale, Mannerim, Marcus Hill Country 3223 Indented Head, Port Arlington, St Leonards Country 3224 Leopold Country 3225 Point Lonsdale, Queenscliffe, Swan Bay, Swan Island Country 3226 Ocean Grove Country 3227 Barwon Heads, Breamlea, Connewarre Country 3228 Bellbrae, Bells Beach, jan Juc, Torquay Country 3230 Anglesea Country 3231 Airleys Inlet, Big Hill, Eastern View, Fairhaven, Moggs -

Fishing on Information Further For

• www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries/recreational at online View any time. any of fish that a person is allowed to have in their possession at at possession their in have to allowed is person a that fish of waters: NSW for rules fishing on information further For • Possession limits: Possession type particular a of number maximum The phones. smart and waters; identified the in taken • for app Guide Fishing Recreational Victorian the Download • Closed seasons: Closed be cannot species fish certain which in period the • or ; www.vic.gov.au/fisheries at online View • Bag limits: Bag day; one in take to permitted are you fish of number • ; 186 136 on Centre Service Customer Call it; keep to allowed be to you for and practices: and • Size limits: Size minimum or maximum size a fish must be in order order in be must fish a size maximum or minimum Recreational Fishing Guide for further information on fishing rules rules fishing on information further for Guide Fishing Recreational recreational fishing. Rules and regulations include: regulations and Rules fishing. recreational Obtain a free copy of the Inland Angling Guide and the Victorian Victorian the and Guide Angling Inland the of copy free a Obtain It is important to be aware of the rules and regulations applying to to applying regulations and rules the of aware be to important is It From most Kmart stores in NSW. in stores Kmart most From • Lake Mulwala Angling Club Angling Mulwala Lake • Fish By the Rules the By Fish agents, and agents, Nathalia Angling Club Angling Nathalia • From hundreds of standard and gold fishing fee fee fishing gold and standard of hundreds From • Numurkah Fishing Club Fishing Numurkah • By calling 1300 369 365 (Visa and Mastercard only), only), Mastercard and (Visa 365 369 1300 calling By • used to catch Spiny Freshwater Crayfish. -

Conservation Advice Polytelis Swainsonii Superb Parrot

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister approved this conservation advice on 5 May 2016; and confirmed this species 16 July 2000 inclusion in the Vulnerable category. Conservation Advice Polytelis swainsonii superb parrot Taxonomy Conventionally accepted as Polytelis swainsonii (Desmarest, 1826). Summary of assessment Conservation status Vulnerable: Criterion 1 A4(a)(c) The highest category for which Polytelis swainsonii is eligible to be listed is Vulnerable. Polytelis swainsonii has been found to be eligible for listing under the following listing categories: Criterion 1: A4(a)(c): Vulnerable Species can be listed as threatened under state and territory legislation. For information on the listing status of this species under relevant state or territory legislation, see http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Reason for conservation assessment by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee The superb parrot was listed as Endangered under the predecessor to the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 and transferred to the EPBC Act in June 2000. This advice follows assessment of information provided by public nomination to change the listing status of Polytelis swainsonii. Public Consultation Notice of the proposed amendment and a consultation document was made available for public comment for greater than 30 business days between 17 November 2014 and 9 January 2015. Any comments received that were relevant to the survival of the species were considered by the Committee as part of the assessment process. Species Information Description The superb parrot is a medium-sized (36–42 cm long; 133–157 g weight) slender, long-tailed green parrot. -

Breeding Ecology of the Superb Parrot, Polytelis Swainsonii In

Technical Report Breeding ecology of the superb parrot Polytelis swainsonii in northern Canberra Laura Rayner, Dejan Stojanovic, Robert Heinsohn and Adrian Manning Fenner School of Environment and Society The Australian National University This report was prepared for Environment and Planning Directorate Australian Capital Territory Government Technical Report: Superb parrot breeding in northern Canberra Acknowledgements This technical report was prepared by Professor Adrian D. Manning and Dr Laura Rayner of the Fenner School of Environment and Society (ANU). Professor Robert Heinsohn and Dr Dejan Stojanovic of the Fenner School of Environment and Society (ANU) were integral to the design and execution of research contained within. Mr Chris Davey contributed many hours of nest searching and monitoring to this project. In addition, previous reports of superb parrot breeding in the study area, prepared by Mr Davey for the Canberra Ornithologists Group, provided critical baseline data for this work. Dr Laura Rayner and Dr Dejan Stojanovic undertook all bird banding, transmitter deployment and the majority of nest checks and tree climbing. Mr Henry Cook contributed substantially to camera maintenance and transmitter retrieval. Additional field assistance was provided by Chloe Sato, Steve Holliday, Jenny Newport and Naomi Treloar. Funding and equipment support were provided by Senior Environmental Planner Dr Michael Mulvaney of the Environment and Planning Directorate (Environment Division) and Ecologist Dr Richard Milner of the Territory and Municipal Services Directorate (ACT Parks and Conservation Service). Spatial data of superb parrot breeding trees and flight paths for the Canberra region were provided by the ACT Conservation Planning and Research Directorate, (ACT Government). Mr Daniel Hill and Mr Peter Marshall of Canberra Contractors facilitated access to a nest tree located within the Throsby Development Area. -

Fire Operations Plan Echuca Murray Valley Hwy Lower Ovens River 2015-2016 Loop Tk Tungamah Rd 2016-2017 E

o! F e d e r a y t i w o n H l W l e a y w e Riverin N a Hwy De niliquin St B ar oog a Rd d R n Fire Operations a Barmah rig er NP - B BARMAH NP LABETTS TRACK B ar CRAWFORDS oo BEARII NORTH ga TRACK - To LADGROVES c um TRACK w a l R Plan d Top Barmah R End RA e NP - SHARPS d l a n PLAIN d s R d Top Island RA GOULBURN New South BARMAH NP- Barmah NP C Wales ob GULF TK ram BOUNDARY - K STRATEGIC oon TRACK oom Barmah NP - oo R St DISTRICT d t War on rm Plain Ve Barmah NP - Cobram Steamers Plain (Lower) Strathmerton Mul wala - Ba rooga Rd Moira Lake COBRAM EAST Barmah d SCOTTS R h NP - t BEACH u o 2015-2016 TO 2017-2018 EDDYS GATE S y w H m a COBRAWONGA - b r Cobram East b b o o C COBRAWONGA C Cobrawonga ISLAND BURN Tocum Track wal Rd d R a row Co t v S A e r n Lake u r o u n o o lb Mulwala Map Legend e B H M ow Picola Katunga S v t A n o ti ra Ba Barmah e Transportation rm d ah R e d Township North F Sprin Wahgunyah Yarrawonga g Dr Freeway alley Hwy Barmah Murray V The Bundalong Willows Highway y Pe B E a rr a r ic rm Waaia r oo Barmah The ah e ta Major Road r - Rd She Katamatite - Yarrawonga Rd v p u p i Ranch arto n Nathalia M R Torrumbarry Rd Pianta Bend y rra Collector Road u r Katamatite - Nathalia Rd M ve Ri Torrumbarry Katamatite - Braund Bend Local Road o! Numurkah y M w Katamatite - Nathalia Rd Railway Line u H rra y y V e l a l ll ! ! ey a V Hw n ! y - r ! Strategic Fuel Break u na b hu Rd l E o u C ca u o ch E G Fire Operations Plan Echuca Murray Valley Hwy Lower Ovens River 2015-2016 Loop Tk Tungamah Rd 2016-2017 E B d Tungamah -

Grand Australia Part Ii: Queensland, Victoria & Plains-Wanderer

GRAND AUSTRALIA PART II: QUEENSLAND, VICTORIA & PLAINS-WANDERER OCTOBER 15–NOVEMBER 1, 2018 Southern Cassowary LEADER: DION HOBCROFT LIST COMPILED BY: DION HOBCROFT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM GRAND AUSTRALIA PART II By Dion Hobcroft Few birds are as brilliant (in an opposite complementary fashion) as a male Australian King-parrot. On Part II of our Grand Australia tour, we were joined by six new participants. We had a magnificent start finding a handsome male Koala in near record time, and he posed well for us. With friend Duncan in the “monster bus” named “Vince,” we birded through the Kerry Valley and the country towns of Beaudesert and Canungra. Visiting several sites, we soon racked up a bird list of some 90 species with highlights including two Black-necked Storks, a Swamp Harrier, a Comb-crested Jacana male attending recently fledged chicks, a single Latham’s Snipe, colorful Scaly-breasted Lorikeets and Pale-headed Rosellas, a pair of obliging Speckled Warblers, beautiful Scarlet Myzomela and much more. It had been raining heavily at O’Reilly’s for nearly a fortnight, and our arrival was exquisitely timed for a break in the gloom as blue sky started to dominate. Pretty-faced Wallaby was a good marsupial, and at lunch we were joined by a spectacular male Eastern Water Dragon. Before breakfast we wandered along the trail system adjacent to the lodge and were joined by many new birds providing unbelievable close views and photographic chances. Wonga Pigeon and Bassian Thrush were two immediate good sightings followed closely by Albert’s Lyrebird, female Paradise Riflebird, Green Catbird, Regent Bowerbird, Australian Logrunner, three species of scrubwren, and a male Rose Robin amongst others. -

'Secret and Deceitful' Brumby Shootings Outrage Sanctuary Builders

Phone 5862 1034 – Fax 5862 2668 – Email - Editorial: [email protected] - Advertising: [email protected] – Registered by Australia Post – Publication No. VA 1548 established 1895 LEADER NumurkahWEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 2021 $1.30 INSIDE Top of her gameNews See story page X3 FIGHTING ... Julie Pridmore is at her wits end after the A cuppa long-standing fi ght with Parks Victoria. See story below. withNews Lou See story pagepages X 7 & 8 ‘Secret and deceitful’ brumby shootings outrage sanctuary builders THE Barmah Brumby Preservation Group animal grazing is having an ongoing impact on the “To ensure the safety of sta and contractors and (BBPG) is claiming that Parks Victoria (PV) has park .” the welfare of horses, operational details of feral been shooting brumbies in the Barmah National e BBPG has accepted that PV will rid the forest horse management operations are not made public- Park, despite agreeing not to shoot any this year. of brumbies, and that some will be shot in order to ly available,” the spokesperson said. With donations coming from right across Victoria, do so. e frustrations of the members of the BBPG Julie explained the BBPG’s side of the story to the Australia, and indeed the world, the BBPG raised lie with PV allegedly going behind their backs and Leader about $90,000 to build a purpose-built ‘sanctuary’, shooting brumbies in recent weeks, despite agreeing “Parks Vic has a strategic plan, that it removes up to on the doorstep of the Barmah National Park, in not to shoot any this year. Julie Pridmore, an active member of the preserva- 100 brumbies by the end of June,” Julie said. -

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria Showing the County, the Land District, and the Municipality in which each is situated. (extracted from Township and Parish Guide, Department of Crown Lands and Survey, 1955) Parish County Land District Municipality (Shire Unless Otherwise Stated) Acheron Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Addington Talbot Ballaarat Ballaarat Adjie Benambra Beechworth Upper Murray Adzar Villiers Hamilton Mount Rouse Aire Polwarth Geelong Otway Albacutya Karkarooc; Mallee Dimboola Weeah Alberton East Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alberton West Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alexandra Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Allambee East Buln Buln Melbourne Korumburra, Narracan, Woorayl Amherst Talbot St. Arnaud Talbot, Tullaroop Amphitheatre Gladstone; Ararat Lexton Kara Kara; Ripon Anakie Grant Geelong Corio Angahook Polwarth Geelong Corio Angora Dargo Omeo Omeo Annuello Karkarooc Mallee Swan Hill Annya Normanby Hamilton Portland Arapiles Lowan Horsham (P.M.) Arapiles Ararat Borung; Ararat Ararat (City); Ararat, Stawell Ripon Arcadia Moira Benalla Euroa, Goulburn, Shepparton Archdale Gladstone St. Arnaud Bet Bet Ardno Follett Hamilton Glenelg Ardonachie Normanby Hamilton Minhamite Areegra Borug Horsham (P.M.) Warracknabeal Argyle Grenville Ballaarat Grenville, Ripon Ascot Ripon; Ballaarat Ballaarat Talbot Ashens Borung Horsham Dunmunkle Audley Normanby Hamilton Dundas, Portland Avenel Anglesey; Seymour Goulburn, Seymour Delatite; Moira Avoca Gladstone; St. Arnaud Avoca Kara Kara Awonga Lowan Horsham Kowree Axedale Bendigo; Bendigo -

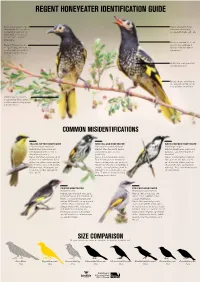

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands.