The News Belongs to Us!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

G by Don Mueller

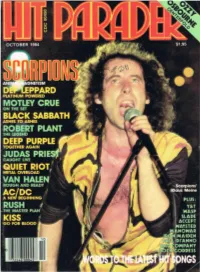

Grace Under Pressure Proves Canadian Trio Remain Masters Of Eclectic Metal. by Don Mueller Geddy Lee sat quietly in Rush's backstage dressing room transfixed by the tiny images on the screen beiore him. "Hey, it's almost time to go on stage:' guitarist Alex Lifeson said, trying to rouse Geddy from his TV obsession. "Not now, not now," Lee shot back in annoyance. "It's the bottom of the ninth, and the Expos are down by one - do you really expect me to leave at a time like this?" Few things can draw the members of Rush away from playing their music, but in the case of Lee, a good baseball game is one of them . "We're so conservative it's sickening," said the hawk-nosed bassist/vocalist. "Most rock and roll bands are into drugs and groupies - we're into sports. There's something about a good baseball game that's very special. Baseball is a lot like the music we play. There's an entertainment value to it, but underneath everything there's a great deal of thought and planning that goes into what's going on. On stage we're like a team, we each have our positions and our specific responsibilities - I guess you could think of us as the Rush All-Stars." With the success of their latest album, Grace Under Pressure, Lee, Weson and drummer Neil Peart have again displayed their league-leading musical skills that over the last decade, have continually made them candidates for the titl rock's Most Valuable Players. -

Cinema of the Dark Side Atrocity and the Ethics of Film Spectatorship

Cinema of the Dark Side Atrocity and the Ethics of Film Spectatorship Shohini Chaudhuri CHAUDHURI 9780748642632 PRINT.indd 1 26/09/2014 16:33 © Shohini Chaudhuri, 2014 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in Monotype Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 4263 2 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 0042 8 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9461 7 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0043 5 (epub) The right of Shohini Chaudhuri to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). CHAUDHURI 9780748642632 PRINT.indd 2 26/09/2014 16:33 Contents Acknowledgements iv List of Figures viii Introduction 1 1 Documenting the Dark Side: Fictional and Documentary Treatments of Torture and the ‘War On Terror’ 22 2 History Lessons: What Audiences (Could) Learn about Genocide from Historical Dramas 50 3 The Art of Disappearance: Remembering Political Violence in Argentina and Chile 84 4 Uninvited Visitors: Immigration, Detention and Deportation in Science Fiction 115 5 Architectures of Enmity: the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict through a Cinematic Lens 146 Conclusion 178 Bibliography 184 Index 197 CHAUDHURI 9780748642632 PRINT.indd 3 26/09/2014 16:33 Introduction n the science fiction film Children of Men (2006), set in a future dystopian IBritain, a propaganda film plays on a TV screen on a train. -

Cambridge Companion Shakespeare on Film

This page intentionally left blank Film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays are increasingly popular and now figure prominently in the study of his work and its reception. This lively Companion is a collection of critical and historical essays on the films adapted from, and inspired by, Shakespeare’s plays. An international team of leading scholars discuss Shakespearean films from a variety of perspectives:as works of art in their own right; as products of the international movie industry; in terms of cinematic and theatrical genres; and as the work of particular directors from Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles to Franco Zeffirelli and Kenneth Branagh. They also consider specific issues such as the portrayal of Shakespeare’s women and the supernatural. The emphasis is on feature films for cinema, rather than television, with strong cov- erage of Hamlet, Richard III, Macbeth, King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. A guide to further reading and a useful filmography are also provided. Russell Jackson is Reader in Shakespeare Studies and Deputy Director of the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. He has worked as a textual adviser on several feature films including Shakespeare in Love and Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet and Love’s Labour’s Lost. He is co-editor of Shakespeare: An Illustrated Stage History (1996) and two volumes in the Players of Shakespeare series. He has also edited Oscar Wilde’s plays. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO SHAKESPEARE ON FILM CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Old English The Cambridge Companion to William Literature Faulkner edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Philip M. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/222 - Total : 8629 Vinyls Au 05/10/2021 Collection "Artistes Divers Toutes Catã©Gorie

Collection "Artistes divers toutes catégorie. TOUT FORMATS." de yvinyl Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage !!! !!! LP GSL39 Etats Unis Amerique 10cc Windows In The Jungle LP MERL 28 Royaume-Uni 10cc The Original Soundtrack LP 9102 500 France 10cc Ten Out Of 10 LP 6359 048 France 10cc Look Hear? LP 6310 507 Allemagne 10cc Live And Let Live 2LP 6641 698 Royaume-Uni 10cc How Dare You! LP 9102.501 France 10cc Deceptive Bends LP 9102 502 France 10cc Bloody Tourists LP 9102 503 France 12°5 12°5 LP BAL 13015 France 13th Floor Elevators The Psychedelic Sounds LP LIKP 003 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Live LP LIKP 002 Inconnu 13th Floor Elevators Easter Everywhere LP IA 5 Etats Unis Amerique 18 Karat Gold All-bumm LP UAS 29 559 1 Allemagne 20/20 20/20 LP 83898 Pays-Bas 20th Century Steel Band Yellow Bird Is Dead LP UAS 29980 France 3 Hur-el Hürel Arsivi LP 002 Inconnu 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys LP 64835 Pays-Bas 38 Special W.w. Rockin' Into The Night LP 64782 Pays-Bas 38 Special Tour De Force LP SP 4971 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Strength In Numbers LP SP 5115 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Special Forces LP 64888 Pays-Bas 38 Special Special Delivery LP SP-3165 Etats Unis Amerique 38 Special Rock & Roll Strategy LP SP 5218 Etats Unis Amerique 45s (the) 45s CD hag 009 Inconnu A Cid Symphony Ernie Fischbach And Charles Ew...3LP AK 090/3 Italie A Euphonius Wail A Euphonius Wail LP KS-3668 Etats Unis Amerique A Foot In Coldwater Or All Around Us LP 7E-1025 Etats Unis Amerique A's (the A's) The A's LP AB 4238 Etats Unis Amerique A.b. -

SPARKS ACROSS the GAP: ESSAYS by Megan E. Mericle, B.A

SPARKS ACROSS THE GAP: ESSAYS By Megan E. Mericle, B.A. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing University of Alaska Fairbanks May 2017 APPROVED: Daryl Farmer, Committee Chair Sarah Stanley, Committee Co-Chair Gerri Brightwell, Committee Member Eileen Harney, Committee Member Richard Carr, Chair Department of English Todd Sherman, Dean College o f Liberal Arts Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School Abstract Sparks Across the Gap is a collection of creative nonfiction essays that explores the humanity and artistry behind topics in the sciences, including black holes, microbes, and robotics. Each essay acts a bridge between the scientific and the personal. I examine my own scientific inheritance and the unconventional relationship I have with the field of science, searching for ways to incorporate research into my everyday life by looking at science and technology through the lens of my own memory. I critique issues that affect the culture of science, including female representation, the ongoing conflict with religion and the problem of separating individuality from collaboration. Sparks Across the Gap is my attempt to parse the confusion, hybridity and interconnectivity of living in science. iii iv Dedication This manuscript is dedicated to my mother and father, who taught me to always seek knowledge with compassion. v vi Table of Contents Page Title Page......................................................................................................................................................i -

Youth Uprising the Lettrist Alternative to Post-War Trauma

Please, return this text to box no. 403 available at museoreinasofia.es Youth Uprising The Lettrist Alternative to Post-War Trauma Lettrism was the first art movement after the Second World War to reintroduce the radicalism of the first avant-garde trends, particularly Dada and Surrealism, and became a communicating vessel for the Neo-avant- garde trends that followed. Lettrism is conceived as a total creative movement, a movement that doesn’t forsake any medium or field of action: poetry, music, film, visual arts or drama. Isou managed to place Lettrism ‘at the vanguard of the avant-garde,’ in contrast with the decline of Dada and Surrealism. During this period Lettrism acquired the true dimension of a group, although the first differences appeared almost at once, producing a split that some years later and in concurrence with other cells of rebe- llious creativity would give rise to the Si- tuationist International. By order of mem- bership, the individuals who joined the first Lettrism is one of the few avant-garde isms that still have a secret history. With the ex- Lettrist group included Gabriel Pomerand, ception of France, its native and almost exclusive soil (radiant Paris, to be more precise), François Dufrêne, Gil Joseph Wolman, the movement was only known superficially, remotely and partially. Ironically, Lettrism Jean-Louis Brau, Serge Berna, Marc’O, is often referred to as an episode prior to Situationism, given the mutual disdain and the Maurice Lemaître, Guy-Ernest Debord, ruthless insults the groups levelled at each other. Furthermore, it is a very complex move- Yolande du Luart and Poucette. -

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

Film Propaganda: Triumph of the Willas a Case Study

Film Propaganda: Triumph of the Will as a Case Study Author(s): Alan Sennett Source: Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, Vol. 55, No. 1 (2014), pp. 45-65 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.13110/framework.55.1.0045 . Accessed: 10/07/2014 11:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 68.191.205.73 on Thu, 10 Jul 2014 11:40:03 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Film Propaganda: Triumph of the Will as a Case Study Alan Sennett Until a reassessment by historians and film critics in the 1990s, Leni Riefenstahl’s cinematic “record” of the September 1934 Nazi party rally had generally been regarded as the quintessential example of the art of political film propaganda. Susan Sontag argued in a seminal article for the New York Review of Books that Riefenstahl’s “superb” films of the 1930s were powerful propaganda as well as important documentary art made by “a film-maker of genius.”1 She concluded that Triumph des Willens/Triumph of the Will (DE, 1935) was “a film whose very conception negates the possibility of the filmmaker’s having an aesthetic concep- tion independent of propaganda.”2 Although still an important source, Sontag’s assessment has been seriously challenged on a number of counts. -

A Study of the Work of Vladimir Nabokov in the Context of Contemporary American Fiction and Film

A Study of the Work of Vladimir Nabokov in the Context of Contemporary American Fiction and Film Barbara Elisabeth Wyllie School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London For the degree of PhD 2 0 0 0 ProQuest Number: 10015007 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10015007 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Twentieth-century American culture has been dominated by a preoccupation with image. The supremacy of image has been promoted and refined by cinema which has sustained its place as America’s foremost cultural and artistic medium. Vision as a perceptual mode is also a compelling and dynamic aspect central to Nabokov’s creative imagination. Film was a fascination from childhood, but Nabokov’s interest in the medium extended beyond his experiences as an extra and his attempts to write for screen in Berlin in the 1920s and ’30s, or the declared cinematic novel of 1938, Laughter in the Dark and his screenplay for Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film version of Lolita. -

A Visionary Book: Charles Nodier's L'h Istoire Du Roi De Boheme Et De Ses Sept Chateaux

A Visionary Book: Charles Nodier's L'H istoire du Roi de Boheme et de ses sept chateaux Anne-Marie Christin ABSTRACT: Charles Nodier's Histoire du Roi de Boheme is original in several respects: it is the first French Romantic illustrated book; it introduces into writing a completely new typographic expressivity; and it represents an aside in the oeuvre of an author torn between "bibliomania" and the love of fantastic tales. The purpose of this article is to analyze the various functions of the image and the typography within L'Histoire du Roi de de Boheme, and to show that these visual representations of the written word, which give the effect of both spectacle and plastic utterance, mark the beginning of a quest that will find its completion many years later. It will also be seen that the author who is thus dispossessed of his control over narration is the very same who is fascinated by the "dispossession" of dreams; and that for him, a compelling necessity links this book to the oneiric inspiration peculiar to his tales. In January of 1830, when L'Histoire du Roi de Boheme et de ses sept chateaux was beginning to appear in bookstores, Charles Nodier wrote: "This is a work which does not strike a responsive chord in any mind, and which is not of this era."1 In point of fact, the book was a commercial fail ure, and it even bankrupted its publisher, Delangle, who fell victim to the considerable expense of its production. "To the loony bin with the King of Bohemia!" was the refrain with which, in a satire by Sci pion Marin two years later, several well-known literary figures attempted to drown out the litany of Nodier's onomatopoeias and quotations assaulting their ears.2 Champfleury, analyzing the principal illustrated books of the Romantic era- of which Nodier's was the first- confirms the book's misunderstood nature: "By its printing, by the accents of its vignettes, the Roi de de Boheme continues to be a most singular note in the world of the Romantic book"; but, he adds, "Nodier wished to be read ... -

The News Belongs to Us!

THE NEWS BELONGS TO US! Moderna galerija / Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana, and Koroška galerija likovnih umetnosti / Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Koroška, Slovenj Gradec 2017 1. MOVIES Andrej Šprah, THE UNCOMPROMISING RETURN OF NEWSREELS 11 Igor Bizjan, THE MOVIE POEMS 26 Thomas Waugh, MELTDOWNS, INTERTEXT, ANCESTORS, MARCHES, MIGRATIONS: NOTES ON NIKA AUTOR AND NEWSREEL FRONT 28 Bill Nichols, NOW. AND THEN… 40 Nika Autor, NEWSREEL SHREDS 44 Nicole Brenez, FILMIC INFORMATION, COUNTERINFORMATION, UR-INFORMATION 54 Darran Anderson, IMPRESSIONS 70 Ivan Velisavljević, SOCIALIST MODERNIZATION IS NOT THE REAL NEWS: YUGOSLAV DOCUMENTARIES OF THE 1960S AND EARLY 1970S 76 2. TRAINS Ciril Oberstar, TRAIN VIEWERS: ON FILMS AND TRAINS 87 Anja Golob, IT’S NOT THE TRAVELS 108 Svetlana Slapšak, ON THE TRAIN. UNDER THE TRAIN. A CHANGE IN ART AND RESPONSIBILITY 110 Matjaž Lunaček, THE READER 114 Anja Golob, THE BIBLE OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 118 Mirjana Dragosavljević, FROM SOLIDARITY TO SOCIALITY 120 Uroš Abram, US? 132 Jelka Zorn, NEWSREEL FRAGMENT, BELGRADE, RAILWAY STATION 138 Zdenka Badovinac, THE BROTHERHOOD AND UNITY HIGHWAY 140 3. PEOPLE Andreja Hribernik, THE LUCK OF THE DRAW AND THE PURSUIT OF (UN)HAPPINESS 147 LOTTERY TICKET 157 Anja Golob, WHAT IS HAPPINESS 158 Miklavž Komelj, SIX FRAGMENTS ON THE LOTTERY 160 Miklavž Komelj, THREE COLLAGES 169 Franco Berardi – Bifo, REELING TRUTH 172 Creative Agitation (Travis and Erin Wilkerson), 100-YEAR-OLD NEWSREEL 184 Sezgin Boynik, MEETING THE TRUTH: ON THE PRACTICE OF FILMING THE UPRISING PEOPLE 210 Igor Španjol and Vladimir Vidmar, WHERE IS THIS TRAIN GOING? SOME NON-BINDING REFLECTIONS ON ART, TOOLS AND MEANING 226 8 9 1.