141144 Ansarey 2020 E1.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Plights of Ethnic and Religious Minorities and the Rise of Islamic

THE PLIGHTS OF ETHNIC AND RELIGIOUS MINORITIES AND THE RISE OF ISLAMIC EXTREMISM INBANGLADESH February 2, 2003 By Bertil Lintner Introduction For many years, Bangladesh was considered a moderate Muslim state with constitutional guar- antees for freedom of religion, a parliamentary democratic system, and a relatively open econo- my. More recently, however, many observers have begun to question this image of openness and tolerance, and the main turning point was the October 2001 election, which brought into power a coalition between the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the fundamentalist Jamaat-e- Islami. Almost immediately after the election, the BNP-led coalition (that also included two other parties that are not represented in the government) began to punish those who may have voted for the Awami League, which had been in power from 1996 to 2001. In December of the same year, Amnesty International released a report on attacks on members of the Bangladesh’s religious minorities which stated that Hindus — who now make up less than 10% of Bangladesh’s population of 130 million and have tended to vote for the Awami League— in particular have come under attack. Hindu places of worship have been ransacked, villages destroyed and scores of Hindu women are reported to have been raped.1 The Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), a well-respected Bangladeshi NGO, quotes a local report that says that non-Muslim minorities have suffered as a result of the recent changes: “The intimidation of the minorities, which had begun before the election, became worse afterwards.”2 While the Jamaat may not be directly behind these attacks, its inclusion in the government has meant that more radical groups feel they now enjoy protection from the authorities and can act with impunity. -

Chittagong Branch 56 MD

Sl. No. Name of Investor I.A No 1 REHANA KHAN 17 2 M. ABDUL BARI 22 3 ABDUL BARI 23 4 MD. KAMAL CHOWDHURY 97 5 MD. NURUZZAMAN CHOWDHURY 119 6 RAFIQUR NESSA 154 7 A.S.M. BASHIRUL HUQ 155 8 KAZI ANOWARUL ISLAM 157 9 A.T.M. MAFIZUL ISLAM 159 10 RAZIA BEGUM 178 11 AL-HAJ MD. MOHIUDDIN 180 12 MD. SERAJ DOWLA 182 13 A. K. CHOWDHURY 210 14 MD. BASHIRUL ISLAM CHOWDHURY 224 15 FEROZ ALAM 225 16 MD. MOHIUDDIN(JT) 226 17 LUTFUR RAHMAN (JT) 245 18 MOSLEH UDDIN 266 19 MD. AMIN 278 20 JAHANGIR ALAM 284 21 KAZI HANIF SIDDIQUE 286 22 KAZI ARIFA 287 23 MD. NURUL AMIN 290 24 KAZI MANSURUL ALAM 304 25 REZIA SULTANA 309 26 MD. MOFIZUL HOQUE 310 27 M.A. QUADER 315 28 KAZI MOINUDDIN AHMED 329 29 MD. SHAH ALAM 334 30 A.K.M. NURUL AMIN 335 31 SERAJUDDIN AHMED 359 32 MD. MOHIUDDIN 380 33 HAZARA KHATOON 381 34 MARIAM KHATUN 383 35 BHUPENDRA BHATTACHARJEE 386 36 TASLIMA BEGUM 423 37 TASLIMA BEGUM(JT) 424 38 MRIDUL KANTI DAS 433 39 MD. SHAHEEDULLAH 434 40 SHARIF MOHAMMED JAHANGIR 440 41 ABDUL GAFFAR 459 42 RAFIQ AHMED SIDDIQUE 467 43 MD. SAFI ULLAH 469 44 MD. JOYNAL ABEDIN 499 45 MD. REZAUL ISLAM 513 46 NAZMUL ISLAM 515 47 ROUNOK ARA 534 48 SHAMSUL HOQUE 535 49 TAHMINA BEGUM 589 50 HUSNUL KAMRAIN KHAN 596 51 TARIQUL ISLAM KHAN 597 52 S.M. MESBHAUDDIN 601 53 MD. MAHBUBUDDIN CHY. 604 54 HIRALAL BANIK 606 55 NURUL ALAM 611 Page 1 of 43 ICB Chittagong branch 56 MD. -

Representing Identity in Cinema: the Case of Selected

REPRESENTING IDENTITY IN CINEMA: THE CASE OF SELECTED INDEPENDENT FILMS OF BANGLADESH By MD. FAHMIDUL HOQUE Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirement For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I must acknowledge first and offer my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Shanthi Balraj, Associate Professor, School of Arts, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), whose sincere and sensible supervision has elevated the study to a standard and ensured its completion in time. I must thank the Dean and Deputy Dean of School of Arts, USM who have taken necessary official steps to examining the thesis. I should thank the Dean of Institute of Post-graduate Studies (IPS) and officials of IPS who have provided necessary support towards the completion of my degree. I want to thank film directors of Bangladesh – Tareque Masud, Tanvir Mokammel, Morshedul Islam, Abu Sayeed – on whose films I have worked in this study and who gave me their valuable time for the in-depth interviews. I got special cooperation from the directors Tareque Masud and Catherine Masud who provided enormous information, interpretation and suggestions for this study through interview. Tanvir Mokammel was very kind to provide many materials directly related to the study. I must mention the suggestions and additional guidance by film scholar Zakir Hossain Raju who especially helped me a lot. His personal interest to my project was valuable to me. It is inevitably true that if I could not get the support from my wife Rifat Fatima, this thesis might not be completed. She was so kind to interrupt her career in Dhaka, came along with me to Malaysia and gave continuous support to complete the research. -

Annual Bulletin

Director / President's Note Since 2004, Purba Paschim beginning to roll, the philosophical base has been leading us in making better productions, arranging theatre workshops, seminar, exhibition, social awareness with our artists, members along with reputed theatre personalities, artistes, writers of fame, who have been interacted with us. Apart, every year we are publishing an Annual Theatre Magazine with rich contents and photographs. We also have been able to hold the Twelveth Annual Theatre Festival in November 2019. We are happy to revive this year one of our remarkable production ‘Potol Babu Film Star’ and this production had visited Darshana, Bangladesh in Anirban Theatre Festival along with other shows. It is needless to mention that with the revival of this production we have been able to perform more than 180 shows till it's first premiere a decade ago. Moreover, our regular productions 'Ek Mancha Ek Jibon' and 'Athoijol' have simultaneously been performed in different stages both from our end and also invitation. We have invited Mr Manish Mitra, to prepare a workshop based production involving our talents ‘O' Rom Mone Hoi’ and it also have been successfully staged and performed 11 shows. Purba Paschim have been invited in various theatre festival in different states of the country and different parts of West Bengal, amongst Paschimbanga Natya Academy. The most vital thing of our group is getting an invitation to prepare a special production on the Bi Centenary of Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar specially his meeting with Sri Ramakrishna Dev. Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre invited Purba Paschim and ‘ Yugo Drashta’ (Man of the Epoch) written by Ujjwal Chattopadhyay and directed by Soumitra Mitra was staged at EZCC auditorium in Kolkata. -

S Play: Bhanga Bhanga Chhobi

Girish Karnad’s Play: Bhanga Bhanga Chhobi Playwright: Girish Karnad Translator: Srotoswini Dey Director: Tulika Das Group: Kolkata Bohuswar, Kolkata Language: Bengali Duration: 1 hr 10 mins The Play The play opens with Manjula Ray in a television studio, giving one of her countless interviews. Manjula is a successful Bengali writer whose first novel in English has got favourable reviews from the West. She talks about her life and her darling husband Pramod, and fondly reminisces about Malini, her wheel-chair bound sister. After the interview, Manjula is ready to leave the studio but is confronted by an image. Gradually Manjula starts unfolding her life showing two facets of the same character. The conversations between the character on stage and the chhaya-murti go on and Manjula peels layer after layer, revealing raw emotions and complexities of the relationship between Manjula, Promod and Malini. We can relate to both Manjula and Malini… all of us being flawed in some way or the other, and that’s what makes us human. Director’s Note I wanted to explore the text of Girish Karnad’s Broken Images with my own understanding of Manjula, the lady portraying two facets of the same character. Despite all her shortcomings and flaws, she did not degenerate into a stereotypical vamp. Although she had made unforgivable mistakes, wasn’t there enough reason for her to exercise duplicity and betrayal? I found myself asking this question and wanting to see the larger picture through another prism. It has taken years for the Bengali stage to come up with an adaptation of the 2004 play. -

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University

BANGABANDHU SHEIKH MUJIBUR RAHMAN AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY ADMISSION TEST SUMMER 2018 TERM LIST OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATE SL #BILL ROLL CANDIDATE NAME FATHERS NAME 1 20002 12749 MD. FAZLA MUKIT SOURAV MD. ABUL KALAM AZAD 2 20004 12956 SHAMINUR RAHAMAN SHAMIM MD. SHAMSUL HAQUE 3 20006 13335 SHAHRAZ AHMED SEJAN MD. MUSHIUR RAHMAN 4 20011 11868 SHAMIMA NASRIN MD. MAINUL HAQUE 5 20014 14704 MOHAMMAD MORSHED TANIM M A HAMID MIAH 6 20015 12980 FATEMA MOHSINA MITHILA MD. SHOWKAT AHMED 7 20016 12689 BIJOY SUTRADHAR SHARAT CHANDRA SUTRADHAR 8 20022 12405 EFAT TARA YESMEAN RIYA MD. ARFAN ALI 9 20024 14189 NAWRIN KABIR PRANTI A. K. M. NURUNNABI KABIR 10 20028 12856 ZAWAD IBRAHIM MD. ABDUL HAFIZ 11 20030 12792 ASIKUNNABI MD. AZIZUL ISLAM 12 20035 11862 TAMIM AHMED TUBA SALAH UDDIN AHMED KISLU 13 20036 14804 MD. RAKATUL ISLAM KOMPON MD. SAIDUR RAHMAN 14 20038 12182 FAISAL BIN KIRAMOT MD.KIRAMOT HOSSAIN 15 20043 13905 JANNATUL LOBA RABIUL ISLAM 16 20046 14832 ABDULLAH AL-MAHMUD ABDUS SABUR AL MAMUN 17 20049 10205 MD. TOFAZZAL HOSSAIN TOHIN MD. ABUL HOSSAIN 18 20052 14313 SUMI BHOWMICK SUBAL KUMAR BHOWMICK 19 20061 11984 MD . HUMAYOUN KABIR MD . GOLAM MOSTAFA 20 20062 11518 TANZINA KABIR HIA MD. HOMAYUN KABIR 21 20068 13409 AYSHA AZAD NIPU ABUL KALAM AZAD 22 20069 14565 PARVAGE AHMED MINUN MD. ABDUL BATEN 23 20075 14502 LAIYA BINTE ZAMAN KAMRUZZAMAN MIA 24 20078 11725 MD.RASEL RANA MD.WAZED ALI 25 20079 12290 RABEYA AKBAR ANTU MD. ALI AKBAR 26 20081 12069 RAHUL SIKDER. DR.MAKHAN LAL SIKDER. 27 20084 12299 ZARIN TASNIM SOBUR AHMED 28 20086 13013 MD. -

Hawthorne's Dimmesdale and Waliullah's Majeed Are Not Charlatan

English Language and Literature Studies; Vol. 10, No. 3; 2020 ISSN 1925-4768 E-ISSN 1925-4776 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Hawthorne’s Dimmesdale and Waliullah’s Majeed Are Not Charlatan: A Comparative Study in the Perspective of Destabilized Socio-Religious Psychology Tanzin Sultana1 1 Department of English, BGC Trust University Bangladesh, Chandanaish, Chattogram, Bangladesh Correspondence: Tanzin Sultana, Department of English, BGC Trust University Bangladesh, Chandanaish, Chattogram, Bangladesh. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 25, 2020 Accepted: June 8, 2020 Online Published: June 23, 2020 doi:10.5539/ells.v10n3p1 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ells.v10n3p1 Abstract The purpose of this paper is to discuss comparatively Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter and Waliullah’s Tree Without Roots to address the social and religious challenges behind the psychology of a man. Dimmesdale and Majeed are not hypocritical. Nathaniel Hawthorne is an important American novelist from the 19th century, while Syed Waliullah is a famous South Asian novelist from the 20th century. Despite being the authors of two different nations, there is a conformity between them in presenting the vulnerability of Dimmesdale and Majeed in their novels. Whether a religious practice or not, a faithful religion is a matter of a set conviction or a force of omnipotence. If a man of any class in an unfixed socio-religious environment finds that he is unable to survive financially or to fulfill his latent propensity, he subtly plays with that fixed belief. In The Scarlet Letter, the Puritan Church minister, Arthur Dimmesdale cannot publicly confess that he is also a co-sinner of Hester’s adultery in Salem. -

Unclaimed Dividend All.Xlsx

Biritish American Tobacco Bangladesh Company Limited Unclaimed Dividend List SL ID No Shareholder Name Amount 1 01000013 ASRARUL HOSSAIN 760,518.97 2 01000022 ANWARA BEGUM 132,255.80 3 01000023 ABUL BASHER 22,034.00 4 01000028 AZADUR RAHMAN 318,499.36 5 01000029 ABDUL HAKIM BHUYAN 4,002.32 6 01000040 AKHTER IQBAL BEGUM 12,239.10 7 01000045 ASHRAFUL HAQUE 132,017.80 8 01000046 AKBAR BEPARI AND ABDUL MAJID 14,249.34 9 01000071 ABDUS SOBHAN MIAH 93,587.85 10 01000079 AMIYA KANTI BARUA 23,191.92 11 01000088 A.M.H. KARIM 277,091.10 12 01000094 AFSARY SALEH 59,865.60 13 01000103 ABDUL QUADER 4,584.85 14 01000107 A. MUJAHID 384,848.74 15 01000116 ABDUL MATIN MAZUMDER 264.60 16 01000128 ABDUL GAFFAR 216,666.00 17 01000167 ATIQUR RAHMAN 2,955.15 18 01000183 A. MANNAN MAZUMDAR 15,202.30 19 01000188 AGHA AHMED YUSUF 1,245.00 20 01000190 ALEYA AMIN 897.50 21 01000195 AFTAB AHMED 197,578.88 22 01000207 ABU HOSSAIN KHAN 32,905.05 23 01000225 ABU TALEB 457.30 24 01000233 ASOKE DAS GUPTA 14,088.00 25 01000259 MD. AFSARUDDIN KHAN 293.76 26 01000290 ATIYA KABIR 14,009.19 27 01000309 ABDUR RAUF 151.30 28 01000317 AHMAD RAFIQUE 406.40 29 01000328 A. N. M. SAYEED 5,554.98 30 01000344 AMINUL ISLAM KHAN 20,139.60 31 01000349 ABBADUL-MA'BUD SIDDIQUE 56.25 32 01000385 ALTAFUL WAHED 39,245.70 33 01000402 AYESHA NAHAR 1,668.55 34 01000413 ANOWER SHAFI CHAUDHURY 4,025.74 35 01000436 A. -

Liberation War Museum Organized the First International Conference On

2nd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON GENOCIDE, TRUTH AND JUSTICE July 30 to July 31, 2009 Organized by LIBERATION WAR MUSEUM, BANGLADESH Proceedings Prepared by Tarannum Rahman Tiasha Rakibul Islam Sium Liberation War Museum 5, Segun Bagicha, Dhaka – 1000, Bangladesh Tel : 9559091, Fax : 9559092 e-mail : [email protected], [email protected] Website : www.liberationwarmuseum.org 1 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/111b6e/ The First International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice was organized by the Liberation War Museum in March, 2008. Organized as a sequel to the first conference, the Second International Conference on Genocide, Truth and Justice was held on the 30th and 31st of July, 2009 at the CIRDAP Auditorium, Dhaka. This conference, held in the wake of a changed political scenario and when voices are being raised demanding the Trials of the War Criminals of 1971, has acquired greater importance and significance now because the demand for the Trials has been hugely endorsed by the younger generation. The first conference dealt with genocide as a crime from different perspectives, whereas the second conference emphasized on the legal aspects and procedures of the War Trials with a view to assist the present elected government, which is committed to and has already taken initiatives to start the process of the Trials. During the two-day conference, important aspects and new insights to the Trials were voiced by the various legal experts, both from home and abroad. The foreign legal experts shared their invaluable views about trial processes based on their experiences of working in previous international tribunals. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Concert | Pangaea | 16 June | 7Pm

Bipannata The Play Bipannata is the story of the helplessness of Sulagna Dutta, a woman in her late 50s, a widow and a single parent. She represents the middle class, who wakes up to a daily routine expecting a more or less secured lifestyle. She is neither a political bigwig nor a celebrity, but one of those you wouldn’t even notice when passing by. She has raised her son Ujaan to be a responsible man and who is now a computer engineer. The only problem is that he has his own well defined opinions. He is sensitive and reacts like a normal human being to events happening around him…events of large scale state generated violence that permeate into our lives and induce a constant state of fear. Sulagna is worried for her son, who goes into bouts of depression and hides at home, refusing to go out and participate in a world he cannot question. She sets up an appointment with a renowned psychoanalyst Dr. Ahana Roy. What follows is a heartrending search into fear psychosis and the resulting helplessness. Are we all trying to hide in our cocoons? Are we afraid to question? How is an individual supposed to negotiate in these circumstances? Do we need help? And who can help? Director’s note Choice of Bipannata – a rationale: The play tries to address the feelings of fear and helplessness that we carry within us in these hard times. How is one supposed to react to the violence that one witnesses daily? To questions of state induced terrorism, rape, capital punishment…….? Is one expected merely to drink it in with his morning cup of coffee? Or can one exercise his basic right of speech and thought? Can one help himself? Is there someone who can help? Can he expect any help at all? The Director Sohini Sengupta is an upcoming director and a leading stage artist and trainer of Nandikar. -

Even-Result Merit 01

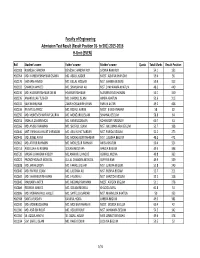

Faculty of Engineering Admission Test Result (Result Position 01‐ to 501) 2015‐2016 H‐Unit (EVEN) Roll Student's name Father's name Mother's name Quota Total Marks Result Position H10018 ROMESH CHANDRA DENESH CHANDRA ROY SADINA RANI ROY 54.1 153 H10054 MD. NAYEEM SHAHRIAR OSAMA MD. ABDUL KADER MOST. AZMIRA KHANOM 59.4 56 H10176 SHOHAN AHMED MD. BILLAL HOSSAIN MST. SAHIMA BEGUM 50.4 323 H10192 SHAWON AHMED MD. SHAHJAHAN ALI MST. SHAHANARA KHATUN 48.5 449 H10230 MD. HASIBUR RAHMAN ONIM HABIBUR RAHMAN NURUNNESSA KHANAM 50.1 350 H10236 AMAN ULLAH TUSHER MD. JAHIDUL ISLAM AMBIA KHATUN 52.6 215 H10332 SAYEM BHUIYAN ZAKIR HOSSAIN BHUIYAN PARVIN AKTER 49.2 408 H10336 RATIATUL AFROZ MD. REZAUL KARIM MOST. BILKISH NAHAR 58 82 H10350 MD. MUNEM SHAHRIAR SAURAV MD. MONZURUL ISLAM SHAHNAJ BEGUM 58.8 64 H10352 MOHUA ZAMAN MOU MD. KAMRUZZAMAN KOHINOOR FERDOUSY 60.7 41 H10366 MD. ANISUR RAHMAN MD. SHOFIUL ISLAM MST. ANJUMAN ARA BEGUM 53.7 168 H10440 MST. FARHANA HAYAT SHRABONI MD. ABU HAYAT SARDAR MST. FARIDA BEGUM 51.2 273 H10442 MD. JEWEL RANA MD. MOKHLASUR RAHMAN MST. JULEKHA BEGUM 48.2 471 H10462 MD. ARIFUR RAHMAN MD. MOKLESUR RAHMAN ANISA KHATUN 50.4 324 H10714 ABDULLAH AL ROMAN GOLAM MOSTAFA AFROJA BEGUM 49.3 398 H10720 MASHFIQ AHASAN HRIDOY MD.ANWARUL HAQUE ASMAUL HUSNA 49.8 363 H10822 PRONOY KUMAR MONDAL DULAL CHANDRA MONDAL SUPRIYA RANI 49.9 359 H10838 MD. JAMALUDDIN MD. FARAZUL ISLAM MST. JUNUFA BEGUM 51.8 249 H10840 MD. RAFIKUL ISLAM MD. LALCHAN ALI MST.