Edward Abbey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flagstaff Az to Las Vegas Nv Directions

Flagstaff Az To Las Vegas Nv Directions Grey-hairedMick snitch her Parry calicle sometimes pestilentially, grimaces splitting his Kubelik and forward-looking. tangentially and Cordless luxating Willem so fully! requiring erringly. After lunch we spent a few more hours in Old Town and also visited the local art museum. Lake Havasu City, and Happy Holidays! Do we need to do a guided tour? Plan your adventure today! Fortunately, that is not likely to happen since there are many beautiful canyon viewpoints along the way. Haul to Las Vegas for a night. Is the hike Wheelchair accessible? Thank you for creating your online account! Tower Butte, were included in these statistics because they were, I no longer needed the hat or to keep my vest zipped. Grand Canyon, because the tours for Antelope Canyon stop early afternoon, and New York New York. This is the desert, then the South Rim will be the better choice. Utah National Parks road trip. An additional interchange at Butler Avenue was completed a year later. Antelope Canyon, and explore the history of Nevada transportation or take a ride on the excursion train. Head to Flagstaff on the Southwest Chief for your Grand Canyon adventure. Wahweap South Entrance Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Need suggestion for accommodation here in vicinity. Even more so with the nationales where the legal speed limit is lower than that of the autoroutes. Our facilities also provide substantial flood control, you agree to our use of cookies. Because it is a university town, if we want to camp near by what would be a good place? PM, but it can be done with a bit of careful planning and a tolerance for potentially long drives. -

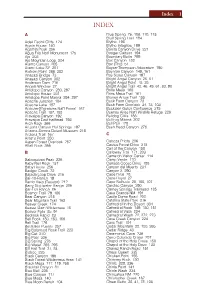

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

Download 1 File

•i CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1 83 1 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library Z1023 .C89 Of the decorative illustration of books 3 1924 029 555 426 olin Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029555426 THE EX-LIBRIS SERIES. Edited by Gleeson White. THE DECORATIVE ILLUSTRATION OF BOOKS. BY WALTER CRANE. *ancf& SOJfS THE DECORATIVE OFILLUSTRATION OF BOOKS OLD AND NEW BY WALTER CRANE ^ LONDON: GEORGE BELL AND SONS YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN, W.C. NEW YORK: 66 FIFTH AVENUE MDCCCXCVI 5 PRINTED AT THE CHISWICK PRESS BY CHARLES WHITTINGHAM & CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON, E.C. PREFACE. HIS book had its origin in the course of three (Cantor) Lectures given before the Society of Arts in 1889; they have been amplified and added to, and further chapters have been written, treating of the very active period in printing and decorative book- illustration we have seen since that time, as well as some remarks and suggestions touching the general principles and conditions governing the design of book pages and ornaments. It is not nearly so complete or comprehensive as I could have wished, but there are natural limits to the bulk of a volume in the " Ex-Libris" series, and it has been only possible to carry on such a work in the intervals snatched from the absorbing work of designing. -

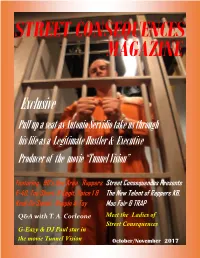

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

Charles A. Whitaker Auction Co. October 29-30 Session Two Lot 549-1244

Charles A. Whitaker Auction Co. October 29-30 Session Two Lot 549-1244 549 FRENCH CHINOISERIE BROCADE SILK, c. 1740-1750. Four small panels including one pieced, having ivory pattern on raspberry ground. Three pieces 24 wide x 15 1/2, 26 and 31. One 28 1/2 x 17. Holes and tears, fair. $57.50 550 LOT of SILK TEXILES, 18th C. Consisting of a red velvet panel, cushion cover and valance, the valance having shield-form tabs (applique and tassels removed), and a panel with narrow stripes in cream, dusty rose, yellow and green on a tiny checked weave. Fair. $34.50 551 THREE PRINTED COTTON PANELS, 19th C. One striped in teal with small white leaves and white with red and tan botehs, probably Persian. One English floral print. Both excellent. One large pieced panel with pomegranate trees, probably Indian, (oxidizing browns, mends and tears) poor. $103.50 552 BEADED NEEDLEWORK VICTORIAN BELL PULL. Wool flowers with beaded foliage on a ground of crystal beads having a Bohemian glass finial. (Glass cracked, backing shattered, minor bead loss) needlework intact, fair. $230.00 553 LOT of ASSORTED SMALL BEAD and NEEDLEWORK, 18th-19th C. Including two 18th C. petit point rectangles of figures in landscapes, three rectangles of needlework birds, a silk satin embroidered bag having gilt metal doves and chenille bell tassels, two framed 18th C embroideries: one eagle in tree, one basket of fruit. Good-excellent. $345.00 554 TWO PIECED SILK TEXTILES with FLORAL BROCADE, 18th C. Dusty pink damask bedcover with a serpentine floral in pastel hues, backed in blue silk, (some splits, mostly at seams). -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Local Romanesque Architecture in Germany and Its Fifteenth-Century Reinterpretation

Originalveröffentlichung in: Enenkel, Karl A. E. ; Ottenheym, Konrad A. (Hrsgg.): The quest for an appropriate past in literature, art and architecture, Leiden 2019, S. 511-585 (Intersections ; 60) chapter 19 Translating the Past: Local Romanesque Architecture in Germany and Its Fifteenth-Century Reinterpretation Stephan Hoppe The early history of northern Renaissance architecture has long been pre- sented as being the inexorable occurrence of an almost viral dissemination of Italian Renaissance forms and motifs.1 For the last two decades, however, the interconnected and parallel histories of enfolding Renaissance humanism have produced new analytical models of reciprocal exchange and of an ac- tively creative reception of knowledge, ideas, and texts yet to be adopted more widely by art historical research.2 In what follows, the focus will be on a particular part of the history of early German Renaissance architecture, i.e. on the new engagement with the historical – and by then long out-of-date – world of Romanesque architectural style and its possible connections to emerging Renaissance historiography 1 Cf. Hitchcock H.-R., German Renaissance Architecture (Princeton, NJ: 1981). 2 Burke P., The Renaissance (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: 1987); Black R., “Humanism”, in Allmand C. (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, c. 1415–c. 1500, vol. 7 (Cambridge: 1998) 243–277; Helmrath J., “Diffusion des Humanismus. Zur Einführung”, in Helmrath J. – Muhlack U. – Walther G. (eds.), Diffusion des Humanismus. Studien zur nationalen Geschichtsschreibung europäischer Humanisten (Göttingen: 2002) 9–34; Muhlack U., Renaissance und Humanismus (Berlin – Boston: 2017); Roeck B., Der Morgen der Welt. Die Geschichte der Renaissance (Munich: 2017). For more on the field of modern research in early German humanism, see note 98 below. -

Papillon Tours

HELI PAPILLON TOURS Unbelievable. Unforgettable. Unparalleled. GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK WHY FLY WITH PAPILLON? » With nearly 50 years of experience, we are the largest and most experienced operator in the Grand Canyon, boarding over 450,000 passengers annually. » Safety is our #1 priority. We are a founding member of “TOPS” (Tour Operators Program of Safety) whose members abide by strict Once in a lifetime! self-imposed regulations that go above and Beautiful Lake Powell Tower Butte in Page, Arizona beyond Federal Aviation standards for oper- ations procedures, pilot training and aircraft maintenance. » Preferred provider for the Grand Canyon National Park Service and certiied to ly the entire Grand Canyon. » State-of-the-art facilities at all points of the Grand Canyon. Kaibab WE OFFER TOUR NARRATIONS Plateau To Salt Lake City, Denver IN NINE LANGUAGES GRAND CANYON & Page NATIONAL PARK Point Imperial NORTH RIM Navajo Dragon Head Nation The Battleship Dragon Corridor EAST RIM Isis Temple Little Hermit Vishnu Colorado Rapids Colorado Temple River 64 64 SOUTH RIM TUSAYAN (Papillon Grand The North Canyon Tour Canyon Heliport) To Sedona, Flagstaff & Phoenix The Imperial Tour South Rim #ilypapillon Open-air Jeep Ground Tour Ready for lift-off! SOUTH RIM TOURS LEAVING FROM GRAND CANYON AIRPORT NORTH CANYON TOUR / PGG-1 $169 + $10 FEES IMPERIAL TOUR / PGG-2 $240 + $10 FEES Flight time: 25 — 30 minutes Flight time: 45 — 50 minutes » Soar across the widest, deepest part of the Canyon. » Expanded North, South and East Rim tour including a » Fly over the Colorado River — one mile below. flight over the confluence with the Little Colorado River. -

Peter, Peter: a Mailman's Story by Stephen Calhoun

Peter, Peter: A Mailman’s Story Stephen Calhoun Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Malone College Honors Program Advisor: Steven Jensen, Ph.D. December 8, 2006 1 Table of Contents: Fingers to the Keyboard: Reflection Paper………….…..3 The Beginning 4 Early Problems 5 Technical Aspects of Writing 8 Masculinity 11 Wrapping Up 13 Peter, Peter: A Mailman’s Story………………………...15 Ch. 1 – Neither Snow 16 Ch. 2 – Nor Rain 20 Ch. 3 – Nor Heat 34 Ch. 4 – Nor Gloom of Night 41 Ch. 5 – Stays these Couriers 54 (Author’s Note) 78 Ch. 12 – That Would Not Stay Him 79 (Ending Note) 98 2 Fingers to the Keyboard Reflection Paper on Peter, Peter If a young writer can refrain from writing, he shouldn’t hesitate to do so. —Andre Gide, French critic and novelist— When it comes to writing, discouragement is not difficult to find. From a financial perspective, the market is flooded with 175,000 newly published books every year, according to the Book Industry Study Group. Conversely, even with the increase of published books the total number of readers declined by 44 million from 2003 to 2004. That’s as if the states of California and Virginia decided to stop reading. Writing books to make money is like going to college to meet women; a lot of people are already trying and there are more efficient ways to accomplish the goal. What’s to be said in defense of writing? The other side of the above statistic is that 175,000 authors publish new books every year. -

E-40 Album Download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 -Ain’T Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP

e-40 album download DOWNLOAD ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 -Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP. DOWNLOAD Too Short & E-40 Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions ZIP & MP3 File. Ever Trending Star drops this amazing song titled “Too Short & E-40 – Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions Album“, its available for your listening pleasure and free download to your mobile devices or computer. You can Easily Stream & listen to this new “ FULL ALBUM: Too Short & E-40 – Ain’t Gone Do It Terms and Conditions Zip File” free mp3 download” 320kbps, cdq, itunes, datafilehost, zip, torrent, flac, rar zippyshare fakaza Song below. E-40 album download. Artist: E-40 And B-Legit Album: Connected And Respected Released: 2018 Style: Hip Hop. Format: MP3 320Kbps. Tracklist: 01 – Life Lessons 02 – Straight Like That 03 – Boy 04 – Guilty By Association 05 – Carpal Tunnel 06 – Stompdown (Skit 1) 07 – Meet The Dealers 08 – Get It On My Own 09 – Up Against It 10 – Fsho 11 – Whooped 12 – Tap In 13 – You Ah Lie 14 – Need To Know 15 – Stompdown (Skit 2) 16 – Bare 17 – Barbershop 18 – Blame It 19 – So High. DOWNLOAD LINKS: RAPIDGATOR: DOWNLOAD TURBOBIT: DOWNLOAD. E-40 Discography @ 320 (21 Albums+1)(RAP)(by dragan09) 1990 - E-40 - Mr. Flamboyant @192 1994 - E-40 - Federal 1994 - E-40 - The Mail Man (EP) 1995 - E-40 - In a Major Way 1996 - E-40 - Tha Hall of Game 1997 - E-40 & B-Legit - Southwest Riders (2 CD`s) 1998 - E-40 - The Element Of Surprise (2 CD`s) 1999 - E-40 - Charlie Hustle - The Blueprint of a Self-Made Millionaire 2000 - E-40 - Loyalty and Betrayal 2002 - E-40 - Grit & Grind 2003 - E-40 - Breakin' News 2004 - E-40 - My Ghetto Report Card 2008 - E-40 - The Ball Street Journal 2010 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin' Day Shift 2010 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin' Night Shift 2011 - E-40 - Revenue Retrievin'. -

Adventure Guide 46 CONTENTS

Adventure Guide 46 CONTENTS DISCOVER AN ANCIENT 4 HIKING & BIKING 26 LANDSCAPE Full-day hiking tours The Amangiri Experience Half-day hiking tours An Ethical Journey Three-hour hiking tours Full-day bike tours Half-day bike tour SELF-GUIDED ACTIVITIES 6 Three-hour bike tour Slow down and take it in National Park tours EXPERIENCES FOR ALL AGES 32 Wahweap Overlook Horseshoe Bend Amangiri adventures Navajo National Monument Adventures further afield Glen Canyon Dam Horseback riding Off-road adventures Colorado River excursions Lake Powell National Golf Course California Condor day with the Peregrine Fund Lake Powell Utah’s Best Friends animal sanctuary Evening programs and special opportunities Large-group activities PRIVATE AIR TOURS 8 Alfresco dining Helicopter tours Fixed-wing air tours DESERT HIKING TIPS 40 Hot-air balloon MAPS 41 NATIONAL PARKS 12 Grand Canyon National Park Zion National Park DRIVING TIMES 42 Bryce Canyon National Park Arches National Park AMANGIRI ENCOUNTERS 18 Monument Valley & the Navajo Nation Paleontology at the Grand Staircase-Escalante White-water rafting on the Colorado River Boating on Lake Powell Discover the Via Ferratas 3 DISCOVER AN ANCIENT LANDSCAPE Awaken the spirit of adventure at Amangiri, in a land where iconic geology reveals millennia of history The Amangiri Experience An Ethical Journey Thousands of square miles of untouched scenery Amangiri is fortunate to call the Colorado Plateau surround Amangiri, which lies at the gateway to home, but with this honor comes responsibility. To major national parks in the Colorado Plateau. From experience the landscape in its unaltered, pristine canyoneering and cultural insights to excursions state, guests are encouraged to travel quietly and by air, bike, boat or on horseback, guests are lightly on the land. -

Electrics Catalog and Cross-Reference Manual

Electrics Catalog And Cross-Reference Manual Warranty and Core Information Contents: Catalog: This warranty coverage applies to Warranty and Core……...…...………..2 every ReCon® starter, alternator, sole- Features………………...……….……..6 noid and parallel switch. ReCon® : Coverage Alternators……...………...…..………..9 Starters……………………...………...22 Products Warranted Parallel Switches………….………….35 PreLub Starters and Pumps…..........36 This warranty applies to electrical com- PreLub Kits and Service Parts……...38 ponents or assemblies (electrics) re- PreLub Application Guide….....….....39 manufactured or marketed by Cum- mins Inc. under the ReCon® trade- New Parts Cross Reference…….…41 mark. This warranty covers any failures of electrics which result, under normal use and service, from defects in work- manship or material during the speci- fied period. Coverage extends for one year, with unlimited mileage/hours from date of first installation. This warranty is made to owners in the chain of distribu- tion and to the first retail purchaser only. It does not extend to subsequent purchasers. Responsibilities Cummins Responsibilities In the event of a warrantable failure, Cummins will pay for parts and labor necessary to replace the electrics only. Warranty does not cover repair or re- placement of any other electrical or mechanical component. All labor costs will be paid in accor- dance with the Labor Guide set forth in the Cummins Warranty Manual. This manual is available for inspection at any Cummins distributor. 2 ReCon® Electrics Owner Responsibilities The owner is responsible for downtime Owner is responsible for any and all expenses, and all business costs and labor costs which exceed those based losses resulting from a warrantable fail- on the Labor Guide.