The Survey of Bath and District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial Inscriptions Bathwick LHS D-426

St Mary the Virgin, Bathwick – Smallcombe Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions Bathwick LHS Row P Names Inscriptions Notes D.P.25 Dorothy Harrison East: Bullock (1836-1914) In Loving Memory Edward Bullock of (1799-) DOROTHY HARRISON BULLOCK 2ND DAUGHTER OF Georgiana Sarah EDWARD BULLOCK ESQRE Bullock (1837-1922) SOME YEARS COMMON SERJEANT OF THE CITY OF LONDON FELL ASLEEP JANUARY 11TH 1914 Cross on 3 plinths. ―•― “HE GIVETH HIS BELOVED SLEEP.” In the 1851 census at 40 Woburn Square, Bloomsbury, London: Edward South: Bullock, aged 51 widower, Common Sergt of London, born at Spanish Also of Town, Jamaica, children: Catherine Elizth, aged 18, born at GEORGIANA Bloomsbury, Dorothy H, aged 14, born at Bloomsbury, and Georgiana, SARAH BULLOCK aged 13, born at Bloomsbury, a governess and three servants. YOUNGER DAUGHTER OF EDWARD BULLOCK ESQRE From The Edinburgh Gazette of Tue 27 Dec 1853 (No. 6346 p1033) FELL ASLEEP APRIL 16TH 1922. WHITEHALL, December 1, 1853. ― The Queen has been pleased to issue a new Commission of “O LORD IN THEE I HAVE TRUSTED.” Lieutenancy for the City of London, constituting and appointing the several persons under-mentioned to be Her Majesty’s Commissioners for that purpose, viz ... Edward Bullock, Esquire, Common Serjeant of Our City of London, and the Common Serjeant of Our said city for the time being; ... In Cambridge University Calendar for the Year 1857 in an advertisement for the English and Irish Church and University Assurance Society, 4, Trafalgar Square, Charing Cross, London on p 40 one of the trustees is: Edward Bullock, Esq., M.A., (Christ Church, Oxford), late Common Serjeant of London. -

Monumental Inscription Information in the Bath Record Office

Monumental Inscription Information in the Bath Record Office Bath Record Office holds transcriptions of memorial inscriptions on tombstones and monuments in some of Bath’s churches and churchyards. Bath Abbey parish Abbey Inscriptions on the Flat Grave Stones in the Bath Abbey Church copied by Charles P Russell (Parish Clerk) at the time of the Restoration of the Church in 1872. Map with handwritten transcripts with some hand-drawn coats of arms. Memorial Inscriptions of Bath Abbey, Transcribed by J Dunn 1912-1914. Typed volume. Arranged in 27 sections according to location with a surname index. Bath Abbey – Burial Register Name & Memorial Indexes. Widcombe Association 2013. Contains name, floor memorial and wall memorial indexes, the memorial indexes based on the preceding documentation of floor and wall memorials. Abbey Cemetery Bath Abbey Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions, Widcombe Association, 2009. A comprehensive documentation of the memorials with images, maps and inscriptions and name and location indexes for those buried in the cemetery. (CD) Abbey & St James’ Poor Cemetery No MIs exists, the site on Lyncombe Hill having been built on. Bathwick Old St Mary’s & St John’s Bathwick Memorial Inscriptions - St Mary’s and St John’s Churches and (Old) Churchyards, The Bathwick Local History Society (2011) (bound volume). Typewritten transcription of inscriptions and maps but no images. St Mary’s Churchyard St Mary’s Churchyard, Bathwick – Memorial Inscriptions, Bathwick Local History Society, 2011. A comprehensive documentation of the memorials with images, inscriptions and name and location indexes for those buried in the cemetery. (Bound volumes.) Smallcombe Vale Cemetery Smallcombe Vale Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions, Bathwick Local History Society, 2011. -

Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE

Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE From the Database of The Commonwealth War Graves Commission Casualties of the AUXILIARY TERRITORIAL SERVICE. From the Database of The Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Austria KLAGENFURT WAR CEMETERY Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 DIXON, Lance Corporal, RUBY EDITH, W/242531. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 4th October 1945. Age 22. Daughter of James and Edith Annie Dixon, of Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. 6. A. 6. TOLMIE, Subaltern, CATHERINE, W/338420. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 14th November 1947. Age 32. Daughter of Alexander and Mary Tolmie, of Drumnadrochit, Inverness-shire. 8. C. 10. Belgium BRUGGE GENERAL CEMETERY - Brugge, West-Vlaanderen Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 MATHER, Lance Serjeant, DORIS, W/39228. Auxiliary Territorial Service attd. Royal Corps of Sig- nals. 24th August 1945. Age 23. Daughter of George L. and Edith Mather, of Hull. Plot 63. Row 5. Grave 1 3. BRUSSELS TOWN CEMETERY - Evere, Vlaams-Brabant Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 EASTON, Private, ELIZABETH PEARSON, W/49689. 1st Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Ser- vice. 25th December 1944. Age 22. X. 27. 19. MORGAN, Private, ELSIE, W/264085. 2nd Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 30th Au- gust 1945. Age 26. Daughter of Alfred Henry and Jane Midgley Morgan, of Newcastle-on-Tyne. X. 32. 14. SMITH, Private, BEATRICE MARY, W/225214. 'E' Coy., 1st Continental Group. Auxiliary Territorial Service. 14th November 1944. Age 25. X. 26. 12. GENT CITY CEMETERY - Gent, Oost-Vlaanderen Commonwealth War Dead 1939-1945 FELLOWS, Private, DORIS MARY, W/76624. Auxiliary Territorial Service attd. 137 H.A.A. Regt. Royal Artillery. 23rd May 1945. Age 21. -

The Survey of Bath and District

The Survey of Bath and District The Magazine of the Survey of Old Bath and Its Associates No.11, June 1999 Editors: Mike Chapman Elizabeth Holland “When did Bath acquire modern trams?” (See inside - Marek Lewcun on the Empire Hotel) Right (Back Cover): Left (Back Cover): 4. Arms of Immanuel Hobbs. 1. Arms of Honor Skrine. HOBBS, impaling Chapman, SKRINE, impaling Hungerford. with the crest of Hobbs. North transept. Ledger-stone in the Choir. _____________ Also included in this issue; • Sources of the Bath Hot Springs: Dr.Kellaway’s report • History of the Bath Mayor’s Honorary Guides • Recollections of Prior Park Road • Beckford’s Tower - its history and the latest developments • Protecting the Architectural Heritage of Bath - a summary of Robin Lambert’s thesis NEWS FROM THE SURVEY 0 The Survey completed its study of the Sawclose area as described in the last issue, and on 27 May 1999 a walk was conducted round the area (see under News from the Friends). It is proposed to make a similar study of the Bimbury area this summer for the Spa Project Team. We have received the grant we applied for from B&NES to publish a booklet on Bimbury. We are now working on our booklet on the Guildhall, in conjunction with Stephen Clews of the Roman Baths Museum. This will concentrate on the Guildhall itself rather than the general area. Elizabeth has been engaged in cataloguing and indexing. A note on her re-arrangement of the Bryant Calendar appears under City News. Under Projects there is a reference to the Survey’s collection of cuttings which we have begun to hand over to the Record Office. -

Church Memorials

SALTFORD MEMORIAL INSCRIPTIONS 2017 Saltford – Memorial Inscriptions Author: P J Bendall Date: 15-Mar-2017 Status: Issue 1 Issue 1 2 Saltford – Memorial Inscriptions Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 2 Graveyard ........................................................................................................................... 6 Old Section ................................................................................................................... 6 New Section ................................................................................................................ 50 Row A ................................................................................................................. 53 Row B ................................................................................................................. 62 Row C ................................................................................................................. 81 Row D ................................................................................................................. 97 Row E ................................................................................................................ 105 Row F ................................................................................................................ 115 Row G ............................................................................................................... -

Memorial Inscriptions Widcombe Association Issue 1

Bath Abbey Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions Widcombe Association Section 4 The top of Row C – Autumn 2007 View northwards towards Widcombe Manor and Crowe Hall. View from main carriageway January 2008 Autumn 2007 The top of Row C – June 2008 View from main carriageway May 2008 From the south-eastern corner. Issue 1 4-1 Bath Abbey Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions Widcombe Association Issue 1 4-2 Bath Abbey Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions Widcombe Association Issue 1 4-3 4 - 4 Widcombe Association Widcombe g (Kent): E 2’6” Blandford. registered was 1856/Q1 The Stuart Churchill birth of The birth of Beatrice Boughton. Golan Hamilton was registered 1864/Q1 Gt In at census thethe Birlin Vicarage, 1891 Stuart Churchill, aged 35, vicar of Birling, born at Stickland (Dorset), wife A[m]elia Georgina, aged 30, born in Ireland, a daughter and four Notes N W G R B S a o a a v a n t C e s c v o r h a i n s n W r t r o c k H F C S S H B T A C S a a h h h r n l e h m u o s l i o a s n i l c t l a w t t i t r b r k t o e e n t y h n l i n y a n r a e b n s u d c k D P P N C S T F E H S W B B C C S B C B B N N L M Q B R B R K a r r i h i e h a v o u e F u o h h a u r o o m h e e o e e u i i e n i i i t t n o a l s e m l c l m l u e e r t w w i i w e b i l l c c a l l a v e s l l d d i p t i a b g m n k s t e a r n n s h h l d i r e b r e e h s o m p e , n c s i m i t s r n r m s n a a t e e r a r r e y n h h o t s t s a s t b t g , r r s y r s r o o s r i n d d l n a i h l n n e n a e s k m 43 39 38 36 35 34 31 30 28 26 25 24 22 20 19 18 16 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 6' 1950 TH BEATRICE WIDOWOF FEB 5 FEB EV EV STUART CHURCHILL IN LOVING OFMEMORY R MY GOD SHALL SUPPLY ALL YOUR NEEDS Inscriptions - 1950) - Memorial Inscriptions Memorial – Names Galan Beatrice (1864 Churchill Stuart (1856 Churchill ) 4A1 Plot Issue 1 Issue Bath Abbey Bath Cemetery Row 4A Bath Abbey Cemetery – Memorial Inscriptions Widcombe Association Plot Names Inscriptions Notes servants. -

Barbara Rotundo Photograph Collection Finding

Special Collections and University Archives UMass Amherst Libraries Barbara Rotundo Photograph Collection Digital ca.1970-2004 4 boxes (3 linear ft.) Call no.: PH 050 About SCUA SCUA home Credo digital Scope Inventory Series 1. Slides Series 2. Photographic prints Series 3. Research Notes Admin info Download xml version print version (pdf) Read collection overview A long-time member of the English Department at the University of Albany, Barbara Rotundo was a 1942 graduate in economics at Mount Holyoke College. After the death of her husband, Joseph in 1953, Rotundo became one of the first female faculty members at Union College, and after earning a master's degree in English at Cornell University and a doctorate in American Literature from Syracuse University, she served as an associate professor of English at the University of Albany, where she founded one of the first university writing programs in the United States. Avocationally, she was a stalwart member of the Association for Gravestone Studies, helping to broaden its scope beyond its the Colonial period to include the Victorian era. Her research included the rural cemetery movement, Mount Auburn Cemetery, white bronze (zinc) markers, and ethnic folk gravestones. Her research in these fields was presented on dozens of occasions to annual meetings of AGS, the American Culture Association, and The Pioneer America Society. In 1989, after residing in Schenectady for forty-six years, she retired to Belmont, NH, where she died in December 2004. Consisting primarily of thousands of color slides (most digitized) and related research notebooks, the Rotundo collection is a major visual record of Victorian grave markers in the United States. -

Full Property Address Primary Liable Party Name Contact Address Rateable Value Description Opp 46, Bath Hill, Keynsham, Bristol

Rateable Full Property Address Primary Liable party name Contact Address Value Description Opp 46, Bath Hill, Keynsham, Bristol, Nndr Dept, 32 Goldsworth Road, BS31 1HG Clear Channel Uk Ltd Woking, Surrey, GU21 6JT 600 Advertising right Junction Of Wellsway, Bath Hill, Nndr Dept, 32 Goldsworth Road, Keynsham, Bristol, BS31 1HG Clear Channel Uk Ltd Woking, Surrey, GU21 6JT 600 Advertising right Adj 2, High Street, Keynsham, Bristol, Nndr Dept, 32 Goldsworth Road, BS31 1DQ Clear Channel Uk Ltd Woking, Surrey, GU21 6JT 600 Advertising right Advertising Right, Corner Of High Rates Manager, Estates Street, Radstock Road, Midsomer Management, Summit House, 27 Norton, Bath, BA3 2AJ Jcdevaux Ltd Sale Place, London, , W2 1YR 1075 Advertising right Adj Bus Shelter, Wells Road, Radstock, Nndr Dept, 32 Goldsworth Road, Bath, BA3 3RS Clear Channel Uk Ltd Woking, Surrey, GU21 6JT 480 Advertising right Adj Bus Shelter, Wells Road, Radstock, Nndr Dept, 32 Goldsworth Road, Bath, BA3 3RS Clear Channel Uk Ltd Woking, Surrey, GU21 6JT 480 Advertising right Adv Right Opp 20, Argyle Terrace, Nndr Dept, 32 Goldsworth Road, Bath, BA2 3DF Clear Channel Uk Ltd Woking, Surrey, GU21 6JT 600 Advertising right Adv Right, Corner Of Newbridge Road Nndr Dept, 32 Goldsworth Road, And, Brassmill Lane, Bath, BA1 3JE Clear Channel Uk Ltd Woking, Surrey, GU21 6JT 600 Advertising right Adj 178, London Road West, Bath, BA1 Nndr Dept, 32 Goldsworth Road, 7QU Clear Channel Uk Ltd Woking, Surrey, GU21 6JT 600 Advertising right Adv Right Adj 1, Midford Road, Bath, Nndr Dept, 32 -

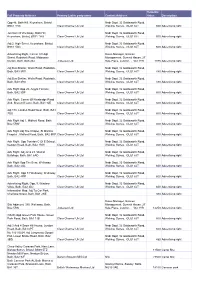

Paradise Preserved: Registered Cemeteries in Date Order with Notes on Principal Reasons for Designation and Designers and Architects

Paradise Preserved: Registered cemeteries in date order with notes on principal reasons for designation and designers and architects 1 Summary English Heritage’s Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest includes 108 cemeteries. There are many other cemeteries of local historic designed landscape interest. This leaflet provides a list of registered cemeteries in date order and names of designers and architects to help assess significance of other cemeteries. The leaflet is published as a supplement to English Heritage’s Paradise Preserved. An introduction to the assessment, evaluation, conservation and management of historic cemeteries published in 2007 and the updated list of registered cemeteries and register criteria (2011). The registered cemeteries span from 1665 to 1967. The majority of registered cemeteries date from 1883 to 1880 with 42 laid out between 1850-60. This correlates with the burst of cemetery development as a consequence of the Burial Acts and the setting up of the new public burial boards to address health and sanitary issues and lack of burial space in cites and towns. The registered cemeteries reflect the range of notable and local designers appointed by the Boards. There are landscape designers of national repute such as John Claudius Loudon, Joseph Paxton, William Gay, Edward Kemp, Edward White and the Milner firm, the Olmsted Brothers from the USA, and Richard Suddell, a President of the Landscape Institute. There are also notable architects Lucy and Littler and Thomas Denville Barry designed cemeteries in the Merseyside area. J P Pritchett, a York based architect, worked on new cemeteries from Boston to Newcastle, and J S Benest designed several cemetery buildings in Norwich. -

Lansdown Cemetery, Bath

LANSDOWN CEMETERY, BATH MEMORIAL INSCRIPTIONS 2012 Lansdown Cemetery Bath Preservation Trust Disclaimer: This volume contains transcriptions of memorial inscriptions from graves, some of which are in poor condition, as well as transcripts of hand-written burial register entries. Naturally, despite careful checking, there may be errors and, if in doubt, the originals should be consulted. Author: Philip J Bendall Date: 2012 Version: Draft Draft ii Lansdown Cemetery Bath Preservation Trust Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 1 History ......................................................................................................... 1 Layout .......................................................................................................... 6 Maintenance .................................................................................................. 7 Registers ....................................................................................................... 8 Notes ......................................................................................................... 10 Occupants ................................................................................................... 11 Individuals of Note ......................................................................................... 12 Known Issues ............................................................................................... -

Cleveland Baths Subscribers 1815 the Individuals Listed Below Are The

Cleveland Baths Subscribers 1815 The individuals listed below are the original subscribers to the Cleveland Baths when the Baths opened in 1815. The information has been collated thanks to the dedicated local history research volunteers who have contributed their time and skills. Austin Thomas. Born in Bath in 1801, the son of a military family, entered the Navy in 1813, and in 1815 had just returned from Quebec where his father had been in the campaign against the US. Was to explore the Arctic in 1824-5. Settled in Canada in 1835 with his wife and children and had a prominent role in the formative Canadian government. In later life became Admiral of Malta dockyard. Source – National Portrait Gallery archives and genealogical site Sir Horatio Thomas Austin 1880 NPG archive Barratt Joseph 1789 – 1824 Bookbinder Source – Much Binding in Bath website Possible burial: Joseph Barratt at Claverton in Apr 1824. Butcher Thomas Possibly Thomas Butcher (1774-1846) From Gye’s Bath Directory 1819: 1 Butcher, Messrs. grocers, and cheese and butter factors, Burton-street Butcher, Mr. T. 15, Kingsmead-terrace Thomas Butcher, aged 72, of Duke St, Bath, died on 30-Aug-1846 and was buried on 3-Sep-1846 at Bathampton (MI). Carpenter Robert. Accountant and auditor with premises on Upper Charles St, Bath. Source – Gye’s Bath Directory 1819 Robert Carpenter (1778-1821) Robert William Carpenter (1806-1883) From Gye’s Bath Directory 1819: Carpenter, R. accomptant and coal-merchant, 6, Trim-street Robert William Carpenter, aged 76, of 12 Prior Park Bldgs, died on 26-Jan- 1883 and was buried in Bath Abbey Cemetery (MI). -

Paradise Preserved an Introduction to the Assessment, Evaluation, Conservation and Management of Historic Cemeteries 9733 EH Paradise Pres 29/12/06 11:26 Page Cov2

9733_EH Paradise Pres 29/12/06 11:26 Page cov1 Paradise Preserved An introduction to the assessment, evaluation, conservation and management of historic cemeteries 9733_EH Paradise Pres 29/12/06 11:26 Page cov2 © English Heritage 2007 with advice and funding from English Nature (now part of Natural England) Text researched and prepared for English Heritage by Roger Bowdler, Seamus Hanna, and Jenifer White and for English Nature (now part of Natural England) by David Knight Edited by Jenifer White and Joan Hodsdon ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Alan Cathersides, Mathew Frith, Seamus Hanna, Ian Hussein, Bill Martin, Simon Mays, Jez Reeve, Julie Rugg and the Cemetery Research Group, Sarah Rutherford, Debbie Thiara, Kit Wedd, Clara Willett Photographs: English Heritage – Building Conservation Research Team (42, 43), Dave Hooley (26, 27), John Lochen (1), Pete Smith (28), Jenifer White (13, 17, 18, 19, 20, 30, 36, 37); Natural England – Stuart Ball/JNCC (45), Mike Hammett (34), Charron Pugsley-Hill (33), Peter Roworth (11), Peter Wakely (12, 44, 46) Photographs © English Heritage and English Heritage.NMR unless otherwise stated.We apologise in advance for any unintentional errors or omissions regarding copyright, which we would be pleased to correct in any subsequent edition. Brought to publication by Joan Hodsdon Chris Brooks’ 1989 book on Victorian and Edwardian cemeteries was the first volume to look at how these special places could be protected and conserved. English Heritage dedicates this publication in memory of his pioneering work. Front cover: The listed grade II* monument of Raja Rammouhun Roy Bahadoor at Arnos Vale Cemetery, Bristol. AA023589 Back cover: A monument in the Urmston Jewish Cemetery, Manchester for Ethel Raphael who died in 1923, aged three years.