Raf Maintenance Personnel - Producers and Supervisors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps AFJROTC

Air Force Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps AFJROTC Arlington Independent School District Developing citizens of character dedicated to serving their community and nation. 1 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 TX-031 AFJROTC WING Texas 31st Air Force Junior ROTC Wing was established in Arlington Independent School District in 1968 by an agreement between the Arlington Independent School District and the United States Air Force. The Senior Aerospace Science Instructor (SASI) is a retired Air Force officer. Aerospace Science Instructors (ASIs) are retired senior non-commissioned officers. These instructors have an extensive background in leadership, management, instruction and mentorship. The students who enroll in Air Force Junior ROTC are referred to as “Cadets”. The entire group of cadets is referred to as a Wing. The Cadet Wing is “owned”, managed and operated by students referred to as Cadet Officers and Cadet Non-commissioned Officers. Using this cadet organization structure, allows cadets to learn leadership skills through direct activities. The attached cadet handbook contains policy guidance, requirements and rules of conduct for AFJROTC cadets. Each cadet will study this handbook and be held responsible for knowing its contents. The handbook also describes cadet operations, cadet rank and chain of command, job descriptions, procedures for promotions, awards, grooming standards, and uniform wear. It supplements AFJROTC and Air Force directives. This guide establishes the standards that ensure the entire Cadet Wing works together towards a common goal of proficiency that will lead to pride in achievement for our unit. Your knowledge of Aerospace Science, development as a leader, and contributions to your High School and community depends upon the spirit in which you abide by the provisions of this handbook. -

PDF File, 139.89 KB

Armed Forces Equivalent Ranks Order Men Women Royal New Zealand New Zealand Army Royal New Zealand New Zealand Naval New Zealand Royal New Zealand Navy: Women’s Air Force: Forces Army Air Force Royal New Zealand New Zealand Royal Women’s Auxilliary Naval Service Women’s Royal New Zealand Air Force Army Corps Nursing Corps Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Officers Vice-Admiral Lieutenant-General Air Marshal No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent Rear-Admiral Major-General Air Vice-Marshal No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent Commodore, 1st and Brigadier Air Commodore No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent 2nd Class Captain Colonel Group Captain Superintendent Colonel Matron-in-Chief Group Officer Commander Lieutenant-Colonel Wing Commander Chief Officer Lieutenant-Colonel Principal Matron Wing Officer Lieutentant- Major Squadron Leader First Officer Major Matron Squadron Officer Commander Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant Second Officer Captain Charge Sister Flight Officer Sub-Lieutenant Lieutenant Flying Officer Third Officer Lieutenant Sister Section Officer Senior Commis- sioned Officer Lieutenant Flying Officer Third Officer Lieutenant Sister Section Officer (Branch List) { { Pilot Officer Acting Pilot Officer Probationary Assistant Section Acting Sub-Lieuten- 2nd Lieutenant but junior to Third Officer 2nd Lieutenant No equivalent Officer ant Navy and Army { ranks) Commissioned Officer No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No equivalent No -

UC Santa Barbara Recent Work

UC Santa Barbara Recent Work Title The Effects of Including Gay and Lesbian Soldiers in the British Armed Forces: Appraising the Evidence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/433055x9 Authors Belkin, Aaron Evans, R.L. Publication Date 2000-11-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE EFFECTS OF INCLUDING GAY AND LESBIAN SOLDIERS IN THE BRITISH ARMED FORCES: APPRAISING THE EVIDENCE Aaron Belkin* and R.L. Evans** November, 2000 The Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military University of Californ ia at Santa Barbara (805) 893 -5664 [email protected] *Director, Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military, University of California, Santa Barbara ** Doctoral candidate, Department of Sociology, University of California, Berkeley I. EXECUTIVE SUMMAR Y Like the U.S. military, the British Services is an all -volunteer force comprised of army, air force and navy contingents. Until January, 2000, when Britain lifted its gay ban following a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights , gay and lesbian soldiers were prohibited from serving in the British Armed Forces. The first ten months of the new policy have been an unqualified success. The military’s own classified, internal assessment at six months found that the new policy has “been hailed as a solid achievement” (Ministry of Defense, 2000e, p. 2). There have been no indications of negative effects on recruiting levels. No mass resignations have occurred. There have been no major reported cases of gay -bashing or harassment of sexual minorities. There have been no major reported cases of harassment or inappropriate behavior by gay or lesbian soldiers. -

The Visiting Forces (Relative Ranks) Regulations 1983

44 1983/6 THE VISITING FORCES (RELATIVE RANKS) REGULATIONS 1983 DAVID BEATfIE, Governor-General ORDER IN COUNCIL At the Government Buildings at Wellington this 7th day of February 1983 Present: THE RIGHT HON. D. MAcINTYRE PRESIDING IN COUNCIL PCRSCA:\"T to section 6 (5) of the Visiting Forces Act 1939, His Excellency the Governor-General, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, hereby makes the following regulations. REGULATIONS 1. Title and conunencement-(l) These regulations may be cited as the Visiting Forces (Relative Ranks) Regulations 1983. (2) These regulations shall come into force on the day after the date of their notification in the Ga;:.ette. 2. Declaration of relative ranks-For the purposes of section 6 of the Visiting Forces Act 1939, the relative ranks of members of the home forces and of the naval, military, and air forces of the United Kingdom, the Commonwealth of Australia, and Tonga respectively shall be those specified in the Schedule to' these regulations. 3. Revocation-The Visiting Forces (Relative Ranks) Regulations 1971* are hereby revoked. ·S.R. 1971/223 1983/6 Visiting Forces (Relative Ranks) Regulations 45 1983 SCHEDULE Reg.2 *TABLE OF RELATIVE RA"KS Ranks in the Home Forces Royal C\'ew Zealand C\'avy New Zealand Army Royal New Zealand Air Force 1. 2. 3. Vice-Admiral Lieutenant-General Air Marshal 4. Rear-Admiral Major-General Air Vice-Marshal 5. Commodore Brigadier Air Commodore 6. Captain Colonel Group Captain Matron-in-Chief 7. Commander Lieutenant-Colonel Wing Commander Principal Matron B. Lieutenant-Commander Major Squadron Leader Matron 9. -

Revised Tri Ser Pen Code 11 12 for Printing

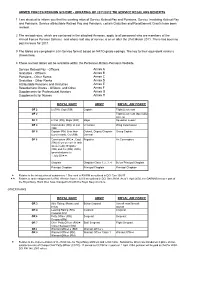

ARMED FORCES PENSION SCHEME - UPRATING OF 2011/2012 TRI SERVICE REGULARS BENEFITS 1 I am directed to inform you that the existing rates of Service Retired Pay and Pensions, Service Invaliding Retired Pay and Pensions, Service attributable Retired Pay and Pensions, certain Gratuities and Resettlement Grants have been revised. 2 The revised rates, which are contained in the attached Annexes, apply to all personnel who are members of the Armed Forces Pension Scheme and whose last day of service is on or after the 31st March 2011. There has been no pay increase for 2011. 3 The tables are compiled in a tri-Service format based on NATO grade codings. The key to their equivalent ranks is shown here. 4 These revised tables will be available within the Personnel-Miltary-Pensions Website. Service Retired Pay - Officers Annex A Gratuities - Officers Annex B Pensions - Other Ranks Annex C Gratuities - Other Ranks Annex D Attributable Pensions and Gratuities Annex E Resettlement Grants - Officers, and Other Annex F Supplements for Professional Aviators Annex G Supplements for Nurses Annex H ROYAL NAVY ARMY ROYAL AIR FORCE OF 2 Lt (RN), Capt (RM) Captain Flight Lieutenant OF 2 Flight Lieutenant (Specialist Aircrew) OF 3 Lt Cdr (RN), Major (RM) Major Squadron Leader OF 4 Commander (RN), Lt Col Lt Colonel Wing Commander (RM), OF 5 Captain (RN) (less than Colonel, Deputy Chaplain Group Captain 6 yrs in rank), Col (RM) General OF 6 Commodore (RN)«, Capt Brigadier Air Commodore (RN) (6 yrs or more in rank (preserved)); Brigadier (RM) and Col (RM) (OF6) (promoted prior to 1 July 00)«« Chaplain Chaplain Class 1, 2, 3, 4 Below Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain « Relates to the introduction of substantive 1 Star rank in RN/RM as outlined in DCI Gen 136/97 «« Relates to rank realignment for RM, effective from 1 Jul 00 as outlined in DCI Gen 39/99. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, Ist January 1972 5

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, IST JANUARY 1972 5 Eric Wingfield MORRELL. Commander John de BEAUFORT-SUCHLICK, Leonard Charles MUNN. Royal Navy. Flying Officer John RAE, Royal Air Force. Acting Commander Philip Robert FLUCK, Miss Pamela SELBY-SMYTH. Royal Navy. Miss Irene Ellen TRY. Commander Joseph David John HAWKSLEY, Royal Navy. Commander Alan Gilbert KENNEDY, Royal CENTRAL CHANCERY OF Navy. THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD Commander Peter Richard David KIMM. ST. JAMES'S PALACE, LONDON s.w.i Royal Navy. Surgeon Commander Francis Michael KINS- 1st January 1972 MAN, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., Royal Navy. THE QUEEN has been graciously pleased to Instructor Commander Ronald Hugh award the Royal Victorian Medal (Silver) to the M^INTOSH, Royal Navy. undermentioned: Commander Gerald Maxwell Braddon SELOUS. V.R.D., Royal Naval Reserve. Royal Victorian Medal (Silver) Commander Kenneth Norman SIMMONDS. Lionel ALLIBONE. Royal Navy. TO958326 Warrant Officer Jesse BAKER, Commander George William Keeton WHIT- B.E M., Royal Air Force. TAKER, Royal Navy. Chief Petty Officer Steward Douglas Gordon CLEARY, P 817054. M.B.E. Victor William EYNON. To be Ordinary Members of the Military V1923391 Chief Technician Sydney Arthur Division of the said Most Excellent Order : FROST, Royal Air Force. Leading Seaman Ronald William GANDER, Fleet Chief Petty Officer Writer Thomas P/JX 898712 McDonald BARR, D/MX 876849. U1812019 Flight Sergeant Alexander Henry Lieutenant Commander Terence Gerard GRAHAM, Royal Air Force. BUTLER, Royal Navy. Frederick Owen HILDRETH. Engineer Lieutenant (AE) Geoffrey John Leslie Donald HILLIER. CARTER, Royal Navy. Alfred John HOLLOWAY. Captain Christopher John Rushall GOODE, Police Constable John McMITTY, Metropolitan Royal Marines. -

Australian Defence Force Ranks

Australian Defence Force ranks The Australian Defence Force's (ADF) ranks of officers and enlisted personnel in each of its three service branches of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), the Australian Army, and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) inherited their rank structures from their British counterparts. The insignia used to identify these ranks are also generally similar to those used in the British Armed Forces. The following tables show the "equivalent rank and classifications" for the three services, as defined in the ADF Pay and Conditions Manual.[1] "Equivalent rank" means the corresponding rank set out under Regulation 8 of the Defence Force Regulations 1952.[2] Contents Commissioned officer ranks Warrant officer ranks Non-commissioned officer ranks Other ranks Insignia Commissioned officers Enlisted See also Notes References External links Commissioned officer ranks NATO Aus/US Code Code Navy Army RAAF Flag/General/Air Officers[1][3] OF-10 O-11[a] Admiral of the fleet Field marshal Marshal of the RAAF OF-9 O-10[b] Admiral General Air chief marshal OF-8 O-9[c] Vice admiral Lieutenant general Air marshal OF-7 O-8 Rear admiral Major general Air vice marshal OF-6 O-7[d] — — Air commodore Senior officers OF-6 O-7[d] Commodore Brigadier — OF-5 O-6[d] Captain (RAN) Colonel Group captain OF-4 O-5[d] Commander Lieutenant colonel Wing commander OF-3 O-4[d] Lieutenant commander Major Squadron leader Junior officers OF-2 O-3[d] Lieutenant Captain (Army) Flight lieutenant OF-1 O-2 Sub lieutenant Lieutenant Flying officer OF-1 O-1 Acting -

Equivalent Ranks of the British Services and U.S. Air Force

EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT Commissioned Ranks Marshal of the Admiral of the Fleet Field Marshal Royal Air Force Command General of the Air Force Admiral Air Chief Marshal General General Vice Admiral Air Marshal Lieutenant General Lieutenant General Rear Admiral Air Vice Marshal Major General Major General Commodore Brigadier Air Commodore Brigadier General Colonel Captain Colonel Group Captain Commander Lieutenant Colonel Wing Commander Lieutenant Colonel Lieutenant Squadron Leader Commander Major Major Lieutenant Captain Flight Lieutenant Captain EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT First Lieutenant Sub Lieutenant Lieutenant Flying Officer Second Lieutenant Midshipman Second Lieutenant Pilot Officer Notes: 1. Five-Star Ranks have been phased out in the British Services. The Five-Star ranks in the U.S. Services are reserved for wartime only. 2. The rank of Midshipman in the Royal Navy is junior to the equivalent Army and RAF ranks. EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. AIR FORCE RoyalT Air RoyalT NavyT ArmyT T UST Air ForceT ForceT Non-commissioned Ranks Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Warrant Officer Class 1 (RSM) Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Warrant Officer Class 2b (RQSM) Chief Command Master Sergeant Warrant Officer Class 2a Chief Master Sergeant Chief Petty Officer Staff Sergeant Flight Sergeant First Senior Master Sergeant Chief Technician Senior Master Sergeant Petty Officer Sergeant Sergeant First Master Sergeant EQUIVALENT RANKS OF THE BRITISH SERVICES AND U.S. -

The London Gazette of FRIDAY, 3Ist JANUARY, 1958 B?

£umb. 41301 771 SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette OF FRIDAY, 3ist JANUARY, 1958 b? Registered as a Newspaper TUESDAY, 4 FEBRUARY, 1958 CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS 411401186 Sergeant Bruce KITCHENER, Royal Air Force. OF KNIGHTHOOD. 3079801 Corporal Harry ACOMB, Royal Air Force. 40846212 Corporal John CANNINGS, Royal Air Force. St. James's Palace, S.W.I. 1 4!I37 554 Junior Technician Raymond Edward ELLIS, 4th February, 1958. Royal Air Force. The QUEEN has been1 graciously pleased to 4134920 Junior Technician Stanley SNOWDON, Royal approve, as on 30th. August, 1957, tihe award of the Air Force. British Empire Medal (Military Division) to:— 41593131 Senior Aircraftman Allison' TAYLOR, Royal 61140212 Flight) Sergeant Donald Ross PHBMN, Royal Air Force. (Air Forces. 545304 Sergeant Patrick Joseph MULHOLLAND, Royal Air Force. Air Ministry, 4th February, 1958. 1338946 Sergeant John Herbert PACKER, Royal Air ROYAL AiIR FORCE. Force. GENERAL DUTIES BRANCH. Appointment to commission ^(permanent). Air Ministry, 4th February, 1958. As Flight Lieutenants (General List):— The QUEEN has 'been graciously pleased to 1st Oct. 1957. approve, as on 30th August, 1957, the following Peter BLAKE (3110014). awards in recognition' of gallant and! distinguished Donald Percy CAREY (583330). service in Malaya:— Joseph Arthur EDWARDS (4036288). Distinguished Flying Cross. John Deryck ROWELL (2324762). Flight (Lieutenant Graham George BAYLISS (71487), •Donald Robert SEALE (2519448). Royal New Zealand- Air Force. Eric SHARP (3509751). Flight Lieutenant Joseph DAVIDSON (200548), Royal James Henry Anthony WINSHIP (4048591). Air Force. George Thomson CANNON (3-124043). 2nd Dec. Flight Lieutenant Laurence John WrrnN-HAYDEN 1957. (56337), Royal- Air Force. As Flying Officers {General List) .— Flying Officer 'Neill "Owen LEARY 031139119), Royal 1st Oct. -

The Queen's Regulations for the Royal Air Force Fifth Edition 1999

UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED The Queen’s Regulations for the Royal Air Force Fifth Edition 1999 Amendment List No 30 QR(RAF AL30/Jun 12 UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED INTENTIONALLY BLANK QR(RAF AL30/Jun 12 UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED Contents CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................................................................1-1 CHAPTER 2 STRUCTURE OF THE SERVICES AND ORGANIZATION OF THE ROYAL AIR FORCE...........................................................2-1 CHAPTER 3 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR OFFICERS.......................................................................................................................................3-1 SECTION 1 - INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMMANDERS.................................................................................................................3-1 SECTION 2 - INSTRUCTIONS FOR OFFICERS GENERALLY...............................................................................................3-17 SECTION 3 - INSTRUCTIONS RELATING TO PARTICULAR BRANCHES OF THE SERVICE.....................................3-18 CHAPTER 4 COMMAND, CORRESPONDING RANK AND PRECEDENCE..........................................................................................................4-1 CHAPTER 5 CEREMONIAL............................................................................................................................................................................................5-1 -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 23Rd January 1968 887

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 23RD JANUARY 1968 887 Flight Lieutenant William Leithhead BERTIE Pilot Officer to Flying Officer : (539380), Royal Air Force. S. G. SHEPHERD, B.Sc. (609362). 15th Jan. Flight Lieutenant John Edward BUCHAN, D.F.M. 1968 (Seniority 15th Apr. 1966). (53436), Royal Air Force Regiment. Flight Lieutenant Michael Minshall CHARLES 21st Jan. 1968 (4231009), Royal Air Force. K. ALDRIDGE (4232850). Flight Lieutenant John Courrs (3045935), Royal J. T. ASHTON (4232786). Air Force. C. J. BILLINGS (4232854). Flight Lieutenant John GOODALL (573975), Royal P. C. BINGHAM (4232840). Air Force. P. A. BYRAM (4232874). Flight Lieutenant Paul Norman HODGETTS R. D. CALVERT (4232833). (4160518), Royal Air Force. B. J. CANFER (4232873). Flight Lieutenant David Anthony Zenthon JAMES A. J. CASSIDY (4232868). (608375), Royal Air Force. D. D. DONALDSON (4232853). Flight Lieutenant Colin Frederick Joseph JONES D. S. GALLANDERS (4232800). (507217), Royal Air Force. M. J. GAMBRELL (4232851). Flight Lieutenant Anthony Brett HUGHES-LEWIS A. K. HILL (4232863). (608405), Royal Air Force. G. HULLEY (4232832). Flight Lieutenant Alexander McMiLLAN (2506878), A. R. JOHNSON (4232838). Royal Air Force. G. C. KAY (4232834). Flight Lieutenant John Bartram MAIN (609235), C. J. KELLY (4232841). Royal Air Force. R. G. KEMP (4232872). Flight Lieutenant Scott Russell MARTIN, M.B., J. M. MCNAUGHTAN (4232856). Ch.B. (2620404), Royal Air Force. M. L. NAYLOR (4232844). Flight Lieutenant Douglas POOLE (517990), Royal C. W. NORRIS (4232842). Air Force. C. PIPER (4232788). Flight Lieutenant Joseph Gerald Romney PRAG, P. N. QUINN (4232884). B.E.M.-,(568308), Royal Air Force. D. S. RIGBY (4232835). Flight Lieutenant Kenneth Charles Harold D. -

Order of the British Empire Wing Commander David Laurence P (5203677C), Royal Air Force

THE LONDON GAZETTE SATURDAY 16 JUNE 2001 SUPPLEMENT No. 1 B7 C.B.E. Flight Sergeant Tony Roy McLure M (D2632843), Royal Auxiliary Air Force. To be Ordinary Commanders of the Military Division of Flight Lieutenant Kevin Anthony P (8181263H), the said Most Excellent Order: Royal Air Force. Group Captain Brian James J , Royal Air Force. Warrant Officer John R (G4278308), Royal Group Captain Peter Rennie O , Royal Air Force. Air Force. Air Commodore Peter William David R , Royal Squadron Leader Michael John S (8285997H), Air Force. Royal Air Force. ff O.B.E. Flight Lieutenant Andrew Geo rey S (0608666E), Royal Air Force Reserve. ffi To be Ordinary O cers of the Military Division of the Squadron Leader William Sidney T (5204918S), said Most Excellent Order: Royal Air Force. Wing Commander Alexander D (0609483S), Royal Squadron Leader Justin W (5207305P), Royal Air Force. Air Force. Wing Commander Mark Francis N (8150987A), Flight Sergeant Peter W (T8124289), Royal Air Royal Air Force. Force. Group Captain Ross P (5205172V), Royal Air Force. Wing Commander David RatcliffeP (5202265K), Royal Air Force. Order of the British Empire Wing Commander David Laurence P (5203677C), Royal Air Force. Wing Commander Wayne R (4335598M), Royal Air (Civil Division) Force. Wing Commander Ashley David S (8127986H), D.B.E. Royal Air Force. To be Ordinary Dames Commander of the Civil Division of the said Most Excellent Order: M.B.E. Professor Ingrid Victoria A (Mrs. Barnes To be Ordinary Members of the Military Division of the Thompson), C.B.E., D.L. For services to Medical said Most Excellent Order: Research.