HOLLYWOOD REPRESENTATIONS of IRISH JOURNALISM: a Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autor/Director Título 51 O Bufón De El Rey DVD 52 Cándido Pazo DVD 53

Hoja1 Número Tipo de Autor/Director Título Observacións Rexistro material 51 Manuel Guede Oliva O Bufón de El Rey DVD 52 Cándido Pazo Nau de amores DVD 53 Antón Reixa El lápiz del carpintero DVD Maiores de 13 anos 54 Autores Varios Lorenzo Varela, un poeta … DVD 55 Autores Varios Manuel Lugrís Freire DVD 56 José Luis Cuerda A lingua das bolboretas DVD 57 José Luis Cuerda La lengua de las mariposas DVD 58 Mareas vivas DVD 59 Chano Piñeiro Sempre Xonxa DVD 60 Ángel de la Cruz/M. Gómez El bosque animado DVD 61 Orson Welles Ciudadano Kane DVD 62 Autores Varios Animales al límite 1: temperatura extrema DVD 64 Keüchi Hara Shinchan- En busca de las bolas perdidas DVD 65 Xoán Cejudo A burla do galo DVD 88 Jorge Coira Entre bateas DVD Maiores de 18 anos 89 Autores Varios As leis de Celavella DVD 90 Keith Goudier Astérix, el golpe de menhir DVD 91 Marcos Nine Pensando en Soledad DVD 92 Gerardo Herrero Heroína DVD Maiores de 13 anos 93 Adolfo Aristarain Martín Hache DVD Maiores de 18 anos 94 Iciar Bollain Te doy mis ojos DVD 95 Alejandro Amenábar Mar adentro DVD 96 Fernando Colomo Al sur de Granada DVD 97 Fabián Bielinsky Nueve reinas DVD 98 Enrique Urbizu La caja 507 DVD 99 Juan José Campanella El hijo de la novia DVD Página 1 Hoja1 100 Alfonso Cuarón Y tu mamá también DVD 101 Javier Fesser La gran aventura de Mortadelo y Filemón DVD 102 Adolfo Aristarain Un lugar en el mundo DVD 103 Alex de la Iglesia Crimen ferpecto DVD Maiores de 18 anos 104 Guillermo del Toro El espinazo del diablo DVD Maiores de 13 anos 105 Juan José Campanella Luna de Avellaneda DVD 106 Montxo Armendáriz Historias del Kronen DVD Maiores de 18 anos 107 Alejandro González Iñárritu Amores perros DVD Maiores de 18 anos 108 Fernando Fernán Gómez El viaje a ninguna parte DVD 109 Adolfo Aristarain Roma DVD Maiores de 13 anos 110 Eduard Cortés La vida de nadie DVD Maiores de 13 anos 111 Tomás Gutierrez Alea/Juan C. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Network Review #37 Cannes 2021

Network Review #37 Cannes 2021 Statistical Yearbook 2020 Cinema Reopening in Europe Europa Cinemas Network Review President: Nico Simon. General Director: Claude-Eric Poiroux Head of International Relations—Network Review. Editor: Fatima Djoumer [email protected]. Press: Charles McDonald [email protected]. Deputy Editors: Nicolas Edmery, Sonia Ragone. Contributors to this Issue: Pavel Sladky, Melanie Goodfellow, Birgit Heidsiek, Ste- fano Radice, Gunnar Rehlin, Anna Tatarska, Elisabet Cabeza, Kaleem Aftab, Jesus Silva Vilas. English Proofreader: Tara Judah. Translation: Cinescript. Graphic Design: Change is good, Paris. Print: Intelligence Publishing. Cover: Bergman Island by Mia Hansen-Løve © DR CG Cinéma-Les Films du Losange. Founded in 1992, Europa Cinemas is the first international film theatre network for the circulation of European films. Europa Cinemas 54 rue Beaubourg 75003 Paris, France T + 33 1 42 71 53 70 [email protected] The French version of the Network Review is available online at https://www.europa-cinemas.org/publications 2 Contents 4 Editorial by Claude-Eric Poiroux 6 Interview with Lucia Recalde 8 2020: Films, Facts & Figures 10 Top 50 30 European movies by admissions Czech Republic in the Europa Cinemas Network Czech exhibitors try to keep positive attitude while cinemas reopen 12 Country Focus 2020 32 France 30 French Resistance Cinema Reopening in Europe 34 46 Germany The 27 Times Cinema initiative Cinema is going to have a triumphant return and the LUX Audience Award 36 Italy Reopening -

The Local and the Global in Anthony Minghella's Breaking and Entering

CULTURA , LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE , LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 · VOL . XI \ 2013, pp. 111-124 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I DOI : HTTP ://DX .DOI .ORG /10.6035/CLR .2013.11.7 Cosmopolitan (Dis)encounters: The Local and the Global in Anthony Minghella’s Breaking and Entering and Rachid Bouchareb’s London River CAROLINA SÁNCHEZ - PALENCIA UNIVERSIDAD DE SEVILLA AB STRA C T : Through the postcolonial reading of Breaking and Entering (Anthony Minghella, 2006) and London River (Rachid Bouchareb, 2009), I mean to analyse the multiethnic urban geography of London as the site where the legacies of Empire are confronted on its home ground. In the tradition of filmmakers like Stephen Frears, Ken Loach, Michael Winterbottom or Mike Leigh, who have faithfully documented the city’s transformation from an imperial capital to a global cosmopolis, Minghella and Bouchareb demonstrate how the dream of a white, pure, uncontaminated city is presently «out of focus», while simultaneously confirming that colonialism persists under different forms. In both films the city’s imperial icons are visually deconstructed and resignified by those on whom the metropolitan meanings were traditionally imposed and now reclaim their legitimate space in the new hybrid and polyglot London. Nevertheless, despite the overwhelming presence of the multicultural rhetoric in contemporary visual culture, their focus is not on the carnival of transcultural consumption where questions of class, power and authority conveniently seem to disappear, but on the troubled lives of its agents, who experience the materially local urban reality as inevitably conditioned by the global forces –international war on terror, media coverage, black market, immigration mafias, corporate business– that transcend the local. -

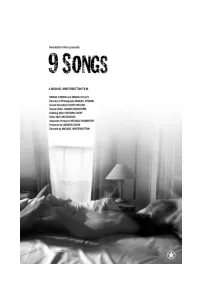

9 SONGS-B+W-TOR

9 SONGS AFILMBYMICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM One summer, two people, eight bands, 9 Songs. Featuring exclusive live footage of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club The Von Bondies Elbow Primal Scream The Dandy Warhols Super Furry Animals Franz Ferdinand Michael Nyman “9 Songs” takes place in London in the autumn of 2003. Lisa, an American student in London for a year, meets Matt at a Black Rebel Motorcycle Club concert in Brixton. They fall in love. Explicit and intimate, 9 SONGS follows the course of their intense, passionate, highly sexual affair, as they make love, talk, go to concerts. And then part forever, when Lisa leaves to return to America. CAST Margo STILLEY AS LISA Kieran O’BRIEN AS MATT CREW DIRECTOR Michael WINTERBOTTOM DP Marcel ZYSKIND SOUND Stuart WILSON EDITORS Mat WHITECROSS / Michael WINTERBOTTOM SOUND EDITOR Joakim SUNDSTROM PRODUCERS Andrew EATON / Michael WINTERBOTTOM EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Andrew EATON ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Melissa PARMENTER PRODUCTION REVOLUTION FILMS ABOUT THE PRODUCTION IDEAS AND INSPIRATION Michael Winterbottom was initially inspired by acclaimed and controversial French author Michel Houellebecq’s sexually explicit novel “Platform” – “It’s a great book, full of explicit sex, and again I was thinking, how come books can do this but film, which is far better disposed to it, can’t?” The film is told in flashback. Matt, who is fascinated by Antarctica, is visiting the white continent and recalling his love affair with Lisa. In voice-over, he compares being in Antarctica to being ‘two people in a bed - claustrophobia and agoraphobia in the same place’. Images of ice and the never-ending Antarctic landscape are effectively cut in to shots of the crowded concerts. -

Tact Thegoodsoup

Administrative Offices 161 Sixth Avenue, 14th Fl 8 TheACTORS COMPANY THEATRE New York, NY 10013 Winter Newsletter 212 645-TACT(8228) 2003/2004 212 255-2053(fax) COMPANY NEWS continued from page 6 www.TACTnyc.org [email protected] tact books: Mostly Harmless and So Long and Thanks anything ... just throwing a 3 year old’s birthday will air in January. He spent the holidays with 2 for All the Fish. party, Hanukkah dinner for the whole family, parents, 2 siblings, their mates, 2 nieces, 2 TACTICS is published TheACTORS COMPANYtactics THEATRE NEWSLETTER twice yearly Larry Keith is currently playing in Tony AND Christmas Eve and Christmas day also for dogs...in his parents 2 bedroom condo on Ft. Vol. 11 No.2 Winter 2003/04 Kushner’s Caroline, or Change at The Public the whole family.” Go home and kiss your Myers Beach. All they were missing was the par- Theater directed by George C. Wolfe. Industry Moms, folks! tridge in the pear tree! scuttlebutt has it that the production may be James Murtaugh and his wife, Alice, graciously Jonathan Smith continues to play the Broadway tact Coming in January! moving to Broadway. Before it does, join the hosted TACT’s annual Holiday Shindig. A good hit, Thoroughly Modern Millie. TheACTORS COMPANY THEATRE There is only one th TACT Theatre Party on January 29 and see time was had by all! James recently shot an David Staller played Higgins again in My Fair Scott Alan Evans, Cynthia Harris & Simon Jones Co-Artistic Directors the show and speak with the cast while it’s still episode of Hope and Faith on ABC starring Kelly Lady which broke box office records at The TACT. -

Katya Thomas - CV

Katya Thomas - CV CELEBRITIES adam sandler josh hartnett adrien brody julia stiles al pacino julianne moore alan rickman justin theroux alicia silverstone katherine heigl amanda peet kathleen kennedy amber heard katie holmes andie macdowell keanu reeves andy garcia keira knightley anna friel keither sunderland anthony hopkins kenneth branagh antonio banderas kevin kline ashton kutcher kit harrington berenice marlohe kylie minogue bill pullman laura linney bridget fonda leonardo dicaprio brittany murphy leslie mann cameron diaz liam neeson catherine zeta jones liev schreiber celia imrie liv tyler chad michael murray liz hurley channing tatum lynn collins chris hemsworth madeleine stowe christina ricci marc forster clint eastwood matt bomer colin firth matt damon cuba gooding jnr matthew mcconaughey daisy ridley meg ryan dame judi dench mia wasikowska daniel craig michael douglas daniel day lewis mike myers daniel denise miranda richardson deborah ann woll morgan freeman ed harris naomi watts edward burns oliver stone edward norton orlando bloom edward zwick owen wilson emily browning patrick swayze emily mortimer paul giamatti emily watson rachel griffiths eric bana rachel weisz eva mendes ralph fiennes ewan mcgregor rebel wilson famke janssen richard gere geena davis rita watson george clooney robbie williams george lucas robert carlyle goldie hawn robert de niro gwyneth paltrow robert downey junior harrison ford robin williams heath ledger roger michell heather graham rooney mara helena bonham carter rumer willis hugh grant russell crowe -

NN Sept 2011.Indd

NOUVELLES THE O HIO S TATE U NIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 2011 AND D IRECTORY NOUVELLES CENTER FOR M EDIEVAL & R ENAISSANCE S TUDIES CALENDAR FALL 2011 28 September 2011 Medieval and Renaissance Graduate Student Association (MRGSA) Meet-and-Greet 308 Dulles Hall 30 September 2011 MRGSA Welcome Party Time and Location TBA 4 October 2011 CMRS Film Series: Merlin, Part I (1998) Directed by Steve Barron, with Sam Neill, Helena Bonham Carter, and John Gielgud 7:30 PM, 056 University Hall 14 October 2011 CMRS Lecture Series: Richard Kagan, Johns Hopkins University Policia and the Plaza: Utopia and Dystopia in the Colonial City 2:30 PM, 090 Science and Engineering Library 18 October 2011 CMRS Film Series: Merlin, Part II (1998) 7:30 PM, 056 University Hall 28 October 2011 CMRS Lecture Series, Music in the Carolingian World Conference Plenary: Michel Huglo, University of Maryland Musica ex numeris 2:30 PM,M, 11 th Floor of Thompsonps Libraryry 1 NovemberNo ve mb er 2201101 1 CMRS Film Series: Mists of Avalon, Part I (2001) Directed by Uli Edel, with Anjelica Huston, Julianna Margulies, and Joan Allen 7:30 PM, 056 University Hall 4 November 2011 MRGSA Colloquium Hays Cape Room, Ohio Union 15 November 2011 CMRS Film Series: Mists of Avalon, Part II (2001) 7:30 PM, 056 University HallHa ll 2 DecemberDe ce mb er 2201101 1 CMRS Lecture Series, Francis Lee Utley Lecture in Folklore Studies: Emily Lethbridge, University of Cambridge The Saga-Steads of Iceland: A 21 st -Century Pilgrimage 2:30 PM, 090 Science and Engineering Library 5 December 2011 Arts and Humanities Centers Holiday Party Time and Location TBA CONTENTS NOUVELLES NOUVELLES SEPTEMBER 2011 AND D IRECTORY CENTER FOR MEDIEVAL AND R ENAISSANCE S TUDIES DIRECTOR Richard Firth Green ASSOCIATE D IRECTOR Sarah-Grace Heller ADMINISTRATIVE C OORDINATOR Nicholas Spitulski GRADUATE A SSOCIATES Michele Fuchs Sarah Kernan Nouvelles Nouvelles is published twice quarterly by the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. -

Unknown Soldier

THE UNKNOWN SOLDIER Produced and Directed by Michael Verhoeven 97 Minutes, Color & B/W, Video, 2006, Germany Dolby SR, 4:3/1:1.85, Dolby Stereo In German with English Subtitles FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building 630 Ninth Avenue, Suite 1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600/Fax (212) 989-7649 www.firstrunfeatures.com [email protected] The Unknown Soldier What Did You Do in the War, Dad? THE FILM ABOUT THE EXHIBITION THAT SHOOK GERMANY The Wehrmacht-Exhibition, shown in eleven major German cities between 1999 and 2004, challenged the people of Germany to rethink what their fathers and grandfathers did during WWII. Most believed that the cold-blooded murder of civilians had been a crime of Adolf Hitler’s Waffen-SS exclusively. But for the first time, German citizens could access photos and films of Wehrmacht soldiers tormenting and executing civilians on the Eastern front. This powerful documentation of seemingly ordinary people committing extraordinary crimes shook Germany, inciting violent protests from those who claimed that the evidence was manufactured. In the wake of this explosive exhibition, director Michael Verhoeven ( The Nasty Girl ) interviews historians and experts, including those who deny the crimes, about the accuracy of these allegations. Filming in the killing fields of Ukraine and Belarus and incorporating archival footage unearthed in the exhibition, Verhoeven weaves a portrait of a nation as it confronts its past. “My father acted on orders…. I am proud of my father.” VISITOR OF THE EXHIBITION 1997 “Berlin rightists mount protest of war exhibition... the sins of the grandfathers.” THE NEW YORK TIMES “The Wehrmacht-Exhibition splits up Germany…the armed forces lost honor.“ LE MONDE “Street battles errupt as neo-Nazis back Hitler‘s army over atrocities.” THE OBSERVER “An Exhibition that has changed the memory of Germany forever“ JAN PHILIPP REEMTSMA “ .. -

Hollywood Representations of Irish Journalism: a Case Study of Veronica Guerin

Irish Communication Review Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 8 January 2009 Hollywood Representations of Irish Journalism: a Case Study of Veronica Guerin Pat Brereton Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons Recommended Citation Brereton, Pat (2009) "Hollywood Representations of Irish Journalism: a Case Study of Veronica Guerin," Irish Communication Review: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 8. doi:10.21427/D78X34 Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol11/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Current Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Communication Review by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License HOLLYWOOD REPRESENTATIONS OF IRISH JOURNALISM : A Case Study of Veronica Guerin Pat Brereton THIS PAPER EMANATES FROM an interest in how the journalist profession is repre - sented on film. This discussion is framed, broadly, by an effort to gauge the perfor - mative nature of journalists, from ‘hard-boiled’ press hacks to egomaniacal TV reporters, while situating the vocation within conventional media studies, which priv - ileges political and ethical indicators like ‘the Fourth Estate’ or as ‘Public Watchdog’. Most recently in the Guardian , Stephen Armstrong presented an overview of how journalists are portrayed on film ( May ), while focusing on an ITV series Midnight Man , where the journalist starring James Nesbitt ends up literally on a rub - bish heap looking for a story. -

SHAY CUNLIFFE Costume Designer

(4/19/21) SHAY CUNLIFFE Costume Designer FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES CAST “PEACEMAKER” James Gunn HBO Max John Cena (Series) The Safran Company Lochlyn Munro Warner Bros TV Robert Patrick “WESTWORLD” Jonathan Nolan HBO Evan Rachel Wood (Season 3) Amanda Marsalis, et al. Bad Robot Aaron Paul Winner: Costume Designers Guild (CDG) Award Thandie Newton Nomination: Emmy Award for Outstanding Fantasy/Sci-Fi Costumes “GONE BABY GONE” Phillip Noyce 20th Century Fox TV Peyton List (Pilot) Miramax Joseph Morgan “BOOK CLUB” Bill Holderman June Pictures Diane Keaton Jane Fonda Candice Bergen Mary Steenburgen “50 SHADES FREED” James Foley Universal Pictures Dakota Johnson Jamie Dornan “50 SHADES DARKER” James Foley Universal Pictures Dakota Johnson Jamie Dornan “A DOG’S PURPOSE” Lasse Hallström Amblin Entertainment Dennis Quaid Walden Media Britt Robertson Pariah “THE SECRET IN THEIR EYES” Billy Ray Gran Via Productions Nicole Kidman IM Global Julia Roberts Chiwetel Ejiofor “GET HARD” Etan Cohen Warner Brothers Will Ferrell Gary Sanchez Kevin Hart Alison Brie “SELF/LESS” Tarsem Singh Ram Bergman Prods. Ryan Reynolds Endgame Ent. Ben Kingsley “THE FIFTH ESTATE” Bill Condon DreamWorks Benedict Cumberbatch Participant Media Laura Linney “WE’RE THE MILLERS” Rawson Thurber New Line Cinema Jennifer Aniston Ed Helms Jason Sudeikis “THE BOURNE LEGACY” Tony Gilroy Universal Pictures Jeremy Renner Rachel Weisz Edward Norton “BIG MIRACLE” Ken Kwapis Universal Pictures Drew Barrymore Working Title Films John Krasinski Anonymous Content Kristen Bell “MONTE -

Veronica Guerin Presskit

Touchstone Pictures Presents was reporting on would make,” he continues. Veronica Guerin “That bravery and courage ultimately made an PRODUCTION INFORMATION enormous difference to her country—without her, it would be a different place.” In the mid-1990s, Dublin was nothing short One of Ireland’s top journalists during the of a war zone, with a few powerful drug lords 1990s, Guerin’s stories focused her nation’s battling for control. Their most fearsome opponent attention on the rising problem of heroin use in was not the police but the courageous journalist Dublin. Painting a vivid picture of a dangerous Veronica Guerin (CATE BLANCHETT), who covered world that perhaps many in the country had not the crime beat with unmatched intensity. As she yet focused upon, Guerin became the sworn investigated and exposed the “pushers,” enemy of the city’s underworld, ultimately balancing her home and family against her galvanizing the anti-drug forces and leading to responsibility to her readers and her country, she stronger drug laws in Ireland. “I like to tell stories became a national folk heroine to the people of about individuals who make a difference in the Ireland. Based on a true story, this powerful, world and are role models for future generations,” emotional film from producer Jerry Bruckheimer, Bruckheimer continues. “To me, that’s Veronica producer of “Pearl Harbor” and “Black Hawk Guerin. She is one of those people who changed Down,” and director Joel Schumacher (“Phone Ireland and the way people thought about drugs Booth,” “Bad Company,” “A Time to Kill,” and criminals.