Naming Places—On and Around Kangaroo Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reserves of the Dudley Peninsula Fire Management Plan 2020

Reserves of the Dudley Peninsula Fire Management Plan 2020 Incorporating: Baudin, Cape Willoughby, Dudley, Lashmar, Lesueur, Pelican Lagoon, & Simpson Conservation Parks For further information please contact: Department for Environment and Water Phone Information Line (08) 8204 1910, or see SA White Pages for your local Department for Environment and Water office. This Fire Management Plan is also available from: https://www.environment.sa.gov.au/topics/fire- management/bushfire-risk-and-recovery Front Cover: KI Narrow-leaved Mallee (Eucalyptus cneorifolia) Woodland by Anne Mclean Disclaimer The Department for Environment and Water and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The Department for Environment and Water and its employees expressly disclaims all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. Permissive Licence This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reference to any company, product or service in this publication should not be taken as a Departmental endorsement of the company, product or service. © Crown in right of the State of South Australia, through the Department for Environment and Water 2020 Preferred way to cite this publication -

01.01.2020 - 21.12.2020

Development Register for Period 01.01.2020 - 21.12.2020 Application No: 520/001/20 Full Development Approval Approved 31/01/2020 Applicants Name Christina McPherson Planning Approval Exempt 15/01/2020 Building Approval Approved 30/01/2020 Applicants Address 7 Chapman Terrace KINGSCOTE SA 5223 Land Division Approval Not Applicable Application Date 09/01/2020 Development Commenced Application Received 15/01/2020 Development Completed Development Description Demolition of house verandah & carport Concurrence Required Relevant Authority Kangaroo Island Council - Delegated to Officer Date Appeal Lodged Appeal Decision House No 7 Lot No 2 Planning Conditions 0 Section No Building Conditions 0 Plan ID FP156436 Land Division Conditions 0 Property Street Chapman Terrace Private Certifier Conditions 0 Property Suburb KINGSCOTE DAC Conditions Title CT5283/117 Hundred of MENZIES NOTE: Conditions assigned to the Development are availabe on request Fees Amount Due Amount Distributed Referred to Schedule 1A Application Fee $55.00 $2.75 Minimum Fee Building Works & Demolition $73.00 $4.65 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 Development Register for Period 01.01.2020 - 21.12.2020 Application No: 520/002/20 Full Development Approval Approved 04/03/2020 Applicants Name Adam Mark Mays Planning Approval Approved 06/02/2020 Building Approval Approved 03/03/2020 Applicants Address PO Box 159 PARNDANA SA 5220 Land Division Approval Not Applicable Application Date 20/01/2020 Development Commenced Application Received 20/01/2020 -

South Australian Geographical Journal

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of South Australia (Inc) (Formerly the Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society (SA Branch)) ISSN: 1030-0481 Vol. 107 2008 Research papers Contents Williams, M.A.J. and Adamson, A biophysical model for the formation of late Pleistocene (107) 1 D.A. valley-fills in the arid Flinders Ranges of South Australia Clark, I.D. and Ryan, E. Aboriginal spatial organization in far northwest Victoria— (107) 15 a reconstruction Bonham, J. Shutting down choice? Freeways, corridors and the politics (107) 49 of micro-spaces Harvey, N., Rudd, D. The 'Sea Change' phenomenon in South Australia (107) 69 and Clarke, B. Wanner, T. Leaving green footprints: South Australia's Strategic Plan (107) 86 and ecological footprint Corcoran, P. Spatial information in Aboriginal and Torres Strait (107) 103 Islander lands and waters management: assisting reconciliation and collaborative development Classics of South Australian Geography Grenfell Price, A. Geographical problems in the founding of South Australia (107) 117 Society Matters One Hundred Years Ago (107) 122 Program of Meetings for 2008 (107) 127 Officers of the Society 2008 (107) 128 Society's publications and price list (107) 129 ISSN: 1030-0481 Vol. 106 2007 Research papers Contents Fornasiero, J., West-Sooby, J., The Brock Lecture.Old Quarrels and new approaches: (106) 1 and Monteath, P. Matthew Flinders and Nicolas Baudin Bourman, R.P. The Geomorphic evolution of Crozier Hill, Fleurieu (106) 16 Peninsula, South Australia: is it ancient glacial landform? Other papers Lothian, A. Landsacpe quality assessment studies in South Australia (106) 27 Lectures Porter, J.R. -

The Meeting of Matthew Flinders and Nicolas Baudin

A Cordial Encounter? 53 A Cordial Encounter? The Meeting of Matthew Flinders and Nicolas Baudin (8-9 April, 1802) Jean Fornasiero and John West-Sooby1 The famous encounter between Nicolas Baudin and Matthew Flinders in the waters off Australia’s previously uncharted south coast has now entered the nation’s folklore. At a time when their respective countries were locked in conflict at home and competing for strategic advantage on the world stage, the two captains were able to set aside national rivalries and personal disappointments in order to greet one another with courtesy and mutual respect. Their meeting is thus portrayed as symbolic of the triumph of international co-operation over the troubled geopolitics of the day. What united the two expeditions—the quest for knowledge in the spirit of the Enlightenment—proved to be stronger than what divided them. This enduring—and endearing—image of the encounter between Baudin and Flinders is certainly well supported by the facts as we know them. The two captains did indeed conduct themselves on that occasion in an exemplary manner, readily exchanging information about their respective discoveries and advising one another about the navigational hazards they should avoid or about safe anchorages where water and other supplies could be obtained. Furthermore, the civility of their meeting points to a strong degree of mutual respect, and perhaps also to a recognition of their shared experience as navigators whom fate had thrown together on the lonely and treacherous shores of the “unknown coast” of Australia. And yet, as appealing as it may be, this increasingly idealized image of the encounter runs the risk of masking some of its subtleties and complexities. -

The Kangaroo Island Tammar Wallaby

The Kangaroo Island Tammar Wallaby Assessing ecologically sustainable commercial harvesting A report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation by Margaret Wright and Phillip Stott University of Adelaide March 1999 RIRDC Publication No 98/114 RIRDC Project No. UA-40A © 1999 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 0 642 57879 6 ISSN 1440-6845 "The Kangaroo Island Tammar Wallaby - Assessing ecologically sustainable commercial harvesting " Publication No: 98/114 Project No: UA-40A The views expressed and the conclusions reached in this publication are those of the author and not necessarily those of persons consulted. RIRDC shall not be responsible in any way whatsoever to any person who relies in whole or in part on the contents of this report. This publication is copyright. However, RIRDC encourages wide dissemination of its research, providing the Corporation is clearly acknowledged. For any other enquiries concerning reproduction, contact the Publications Manager on phone 02 6272 3186. Researcher Contact Details Margaret Wright & Philip Stott Department of Environmental Science and Management University of Adelaide ROSEWORTHY SA 5371 Phone: 08 8303 7838 Fax: 08 8303 7956 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: http://www.roseworthy.adelaide.edu.au/ESM/ RIRDC Contact Details Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation Level 1, AMA House 42 Macquarie Street BARTON ACT 2600 PO Box 4776 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Phone: 02 6272 4539 Fax: 02 6272 5877 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.rirdc.gov.au Published in March 1999 Printed on environmentally friendly paper by Canprint ii Foreword The Tammar Wallaby on Kangaroo Island, South Australia, is currently managed as a vertebrate pest. -

BIOLOGICAL SURVEY of KANGAROO ISLAND SOUTH AUSTRALIA in NOVEMBER 1989 and 1990

A BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF KANGAROO ISLAND SOUTH AUSTRALIA IN NOVEMBER 1989 and 1990 Editors A. C. Robinson D. M. Armstrong Biological Survey and Research Section Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs, South Australia 1999 i Kangaroo Island Biological Survey The Biological Survey of Kangaroo Island, South Australia was carried out with the assistance of funds made available by, the Commonwealth of Australia under the 1989-90 National Estate Grants Programs and the State Government of South Australia. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Australian Heritage Commission or the State Government of South Australia. The report may be cited as: Robinson, A. C. & Armstrong, D. M. (eds) (1999) A Biological Survey of Kangaroo Island, South Australia, 1989 & 1990. (Heritage and Biodiversity Section, Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs, South Australia). Copies of the report may be accessed in the library: Environment Australia Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs GPO Box 636 or 1st Floor, Roma Mitchell House CANBERRA ACT 2601 136 North Terrace, ADELAIDE SA 5000 EDITORS A.C. Robinson, D.M. Armstrong, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage &Biodiversity Section, Department for Environment Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs PO Box 1047 ADELAIDE 5001 AUTHORS D M Armstrong, P.J.Lang, A C Robinson, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage &Biodiversity Section, Department for Environment, Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs PO Box 1047 ADELAIDE 5001 N Draper, Australian Cultural Heritage Management Pty Ltd, 53 Hackney Rd. HACKNEY, SA 5069 G Carpenter, Biodiversity Monitoring and Evaluation, Heritage &Biodiversity Section, Department for Environment Heritage and Aboriginal Affairs. -

Native Vegetation Council 81 -95 Waymouth St, ADELAIDE SA 5000 | GPO Box 1047, ADELAIDE SA 5001 Ph| 08 8303 9777; Email| [email protected]

Native Vegetation Council 81 -95 Waymouth St, ADELAIDE SA 5000 | GPO Box 1047, ADELAIDE SA 5001 Ph| 08 8303 9777; email| [email protected] DECISION NOTIFICATION Native Vegetation Regulations 2017 Application Number: 2021/3023/520 To: Attention: Tim Kildea Date Received: 21/12/2020 A/Manager Environment, Land & Heritage Expertise Date Registered: 02/02/2021 SA Water 250 Victoria Square ADELAIDE SA 5000 Email: [email protected] Ph: 08 7424 3620 Mob: 0418 212 680 Applicant SA Water Landholder Commissioner of Highways (Department for Infrastructure and Transport) Purpose of application Clearance required to construct a pipeline to augment the security and distribution of water supply on Kangaroo Island. Description of native 1.56 ha native vegetation on roadsides, including the following plant vegetation under application associations: Allocasuarina muelleriana shrubland Eucalyptus cneorifolia mallee Melaleuca halmaturorum shrubland Eucalyptus cosmophylla mallee Eucalyptus diversifolia mallee Eucalyptus rugose mallee Myoporum insulare coastal shrubland Leucopogon parviflorus coastal shrubland Location of the application Local Government Area: Kangaroo Island Council Parcel ID/Title ID: n/a - road reserve. Hundred of Dudley The pipeline is planned in two stages. Stage 1 extends from the Middle River water main on Playford Highway near Kangaroo Island Airport along Arranmore Road and Hog Bay Road to Pelican Lagoon. Stage 2 extends from Pelican Lagoon along Hog Bay Road to reach the desalination plant water storage at Charing Cross Road, Kangaroo Head. Decision The Native Vegetation Council has considered your application in accordance with the requirements of Regulation 12, Schedule 1; Clause 34 of the Native Vegetation Regulations 2017. In respect of the application, you are informed that the Native Vegetation Council: - 2 - 1. -

40 Great Short Walks

SHORT WALKS 40 GREAT Notes SOUTH AUSTRALIAN SHORT WALKS www.southaustraliantrails.com 51 www.southaustraliantrails.com www.southaustraliantrails.com NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Sturt River Stony Desert arburton W Tirari Desert Creek Lake Eyre Cooper Strzelecki Desert Lake Blanche WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN Outback Great Victoria Desert Lake Lake Flinders Frome ALES Torrens Ranges Nullarbor Plain NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Lake Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Gairdner Sturt 40 GREAT SOUTH AUSTRALIAN River Stony SHORT WALKS Head Desert NEW SOUTH W arburton of Bight W Trails Diary date completed Trails Diary date completed Tirari Desert Creek Lake Gawler Eyre Cooper Strzelecki ADELAIDE Desert FLINDERS RANGES AND OUTBACK 22 Wirrabara Forest Old Nursery Walk 1 First Falls Valley Walk Ranges QUEENSLAND A 2 First Falls Plateau Hike Lake 23 Alligator Gorge Hike Blanche 3 Botanic Garden Ramble 24 Yuluna Hike Great Victoria Desert 4 Hallett Cove Glacier Hike 25 Mount Ohlssen Bagge Hike Great Eyre Outback 5 Torrens Linear Park Walk 26 Mount Remarkable Hike 27 The Dutchmans Stern Hike WESTERN AUSTRALI WESTERN Australian Peninsula ADELAIDE HILLS 28 Blinman Pools 6 Waterfall Gully to Mt Lofty Hike Lake Bight Lake Frome ALES 7 Waterfall Hike Torrens KANGAROO ISLAND 0 50 100 Nullarbor Plain 29 8 Mount Lofty Botanic Garden 29 Snake Lagoon Hike Lake 25 30 Weirs Cove Gairdner 26 Head km BAROSSA NEW SOUTH W of Bight 9 Devils Nose Hike LIMESTONE COAST 28 Flinders -

The Kangaroo Island China Stone and Clay Company and Its Forerunners

The Kangaroo Island China Stone and Clay Company and its Forerunners ‘There’s more stuff at Chinatown – more tourmalines, more china clay, silica, and mica – than was ever taken out of it’. Harry Willson in 1938.1 Introduction In September 2016 a licence for mineral exploration over several hectares on Dudley Peninsula, Kangaroo Island expired. The licensed organisation had searched for ‘ornamental minerals’ and kaolin.2 Those commodities, tourmalines and china stone, were first mined at this site inland and west of Antechamber Bay some 113 years ago. From March 1905 to late 1910, following the close of tourmaline extraction over 1903-04, the Kangaroo Island China Stone and Clay Company mined on the same site south-east of Penneshaw, and operated brick kilns within that township. This paper outlines the origin and short history of that minor but once promising South Australian venture. Tin and tourmaline The extensive deposits inadvertently discovered during the later phase of tourmaline mining were of china (or Cornish) stone or clay (kaolin), feldspar (basically aluminium silicates with other minerals common in all rock types), orthoclase (a variant of feldspar), mica, quartz, and fire-clay. The semi-precious gem tourmaline had been chanced upon in a corner trench that remained from earlier fossicking for tin.3 The china stone and clay industry that was poised to supply Australia’s potteries with almost all their requisite materials and to stimulate ceramic production commonwealth-wide arose, therefore, from incidental mining in the one area.4 About 1900, a granite dyke sixteen kilometres south-east of Penneshaw was pegged out for the mining of allegedly promising tin deposits. -

Working Together

Working together Achievements 2014–2015 Contents Foreword 4 Leading natural resources management 5 Measuring performance 7 Managing water 9 Managing land condition 11 Managing island parks 13 Managing Seal Bay 15 Managing coasts and seas 17 Managing biodiversity 19 Managing fire 21 Managing threatened plants 23 2015© Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Managing glossy black-cockatoos 25 ISBNs Printed: 978-1-921595-19-6 On-line: 978-1-921595-20-2 Managing feral animals 27 This document may be reproduced in whole or part for the purpose of study or training, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and to its not being used for commercial purposes or sale. Managing koalas 29 Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires the prior written permission of the Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board. Managing weeds 31 All images within this document are credited to Natural Resources Kangaroo Island unless stated otherwise. Working with volunteers 33 Front cover image: Ivy Male helps Heiri Klein to plant glossy black-cockatoo habitat. Working with junior primary students 35 Back cover image: Green carpenter bee. Working with primary students 37 Work outlined in this document is funded by: Working with land managers 39 1 2 2 Foreword With the release of the State Government’s The board and Kangaroo Island Council top economic priorities, the Kangaroo Island are advocating for a feral cat free island. region has been placed firmly in the spotlight Eradication of feral cats will take considerable with Kangaroo Island Natural Resources government, private and community resources. -

Working Together Our Achievements 2009 – 2016

Working together Our achievements 2009 – 2016 Photo and logos needed 1 2016© Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources ISBN: 978-1-921595-24-0 This document may be reproduced in whole or part for the purpose of study or training, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source and to its not being used for commercial purposes or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires the prior written permission of the Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board. All images within this document are credited to Natural Resources Kangaroo Island unless stated otherwise. Front cover image: Travis Bell and Grant Flanagan inspecting crop health as part of the AgKI Potential Project. Work outline in this document is funded by: 2 2 Message from the Presiding Member 4 Message from the Regional Director 5 Socio-economic Snapshot 6 Culture & Heritage Snapshot 8 Flora Snapshot 10 Fauna Snapshot 14 Marine & Coastal Snapshot 18 Freshwater Snapshot 22 Land Condition Snapshot 26 Biosecurity & Pests Snapshot 30 Climate Change Snapshot 34 Community Engagement & Capacity Building Snapshot 38 A New NRM Plan for KI 42 3 3 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDING MEMBER The inaugural Kangaroo Island Natural Resources 2009, fencing off native vegetation, installing creek crossings Management (NRM) Plan 2009–2019 was prepared when and liming acid soils. Kangaroo Island was declared one of eight South Australian However, some systems are out of balance, particularly where NRM regions under the Natural Resources Management Act human activities have tipped the scales, and many plant 2004, and while Kangaroo Island may be the smallest region and animal species continue to decline in numbers on the geographically, it is certainly one of the most precious! island, including top order predators such as the Rosenberg’s The Kangaroo Island community is deeply connected to goanna and osprey. -

Lsvbstigator Stratr

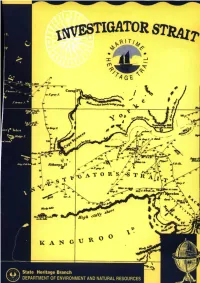

p lSVBSTIGATOR STRAtr Wtdftt l. rJ r—A* State Heritage Branch S DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Slate Heritage Branch Department of Environment and Natural Resources Text by Terry Arnott Design and illustrations by Design Publishing Unit Adelaide, 1996 ISBN 0 7308 4720 9 F1S 14983 0VBSTIGATOR STKajj, '/Tv • v CONTENTS page Introduction 1 Map showing Investigator Strait Shipwrecks 8 Table of Investigator Strait Shipwrecks 9 S.S .Clan Ranald 10 Ethel 14 S.S .Ferret 16 Hougomont 18 S.S. Marion 21 S.S. Pareora 24 S.S. Willy a ma 27 Yatala Reef 30 Althorpe Island Shipwrecks 32 References 34 Diver Services 35 NOTES 36 The steering quadrant is visible above water as a diver examines the Willyama's sternpost. INVESTIGATOR strait INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Investigator Strait Maritime Heritage Trail. An historical background nvestigator Strait is the extensive and navigable stretch of water which I lies between southern YorkejEeninsula"ancfeKangaroo Island. Captain Matthew Flinders gave it this-name'on. in honour of his ship, HMS Investigator. jm " \ South Australia has over 3OOOokilo'rrie fres of coastline, deeply indented by mwA! lij.i| two gulfs, Gulf St. Vincent andfeSpencer-sGulffaiiwhichSare Winked at their southern approacheh s bh y thtvSe waters'of Investigator Strait. From the middlHH.e of last century Investigator Strait\nas,played an important part'in the trade and Vl^x , — \/ communications network of\SouthvAustralia as a^natural route for shipping. j^ II The first ships to use the strait\oir?a$r,egular basis were engaged in early f _ A whaling and sealing ventures.