A Conceptual and Methodological Framework for Modelling and Analysis of Information Demand in an Enterprise Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autonomous Vehicles in Support of Naval Operations Committee on Autonomous Vehicles in Support of Naval Operations, National Research Council

Autonomous Vehicles in Support of Naval Operations Committee on Autonomous Vehicles in Support of Naval Operations, National Research Council ISBN: 0-309-55115-3, 256 pages, 6 x 9, (2005) This free PDF was downloaded from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11379.html Visit the National Academies Press online, the authoritative source for all books from the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council: • Download hundreds of free books in PDF • Read thousands of books online, free • Sign up to be notified when new books are published • Purchase printed books • Purchase PDFs • Explore with our innovative research tools Thank you for downloading this free PDF. If you have comments, questions or just want more information about the books published by the National Academies Press, you may contact our customer service department toll-free at 888-624-8373, visit us online, or send an email to [email protected]. This free book plus thousands more books are available at http://www.nap.edu. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. Permission is granted for this material to be shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this notice appears on the reproduced materials, the Web address of the online, full authoritative version is retained, and copies are not altered. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written permission from the National Academies Press. Autonomous Vehicles in Support of Naval Operations http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11379.html AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES IN SUPPORT OF NAVAL OPERATIONS Committee on Autonomous Vehicles in Support of Naval Operations Naval Studies Board Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. -

Optimalizácia Využívania Internetových Sietí V Regióne Košice

Article history: Received 20 November 2019 TRANSPORT & LOGISTICS: Accepted 31 December 2019 the International Journal Available online 09 January 2020 ISSN 2406-1069 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Article citation info: Pacaiova, H., Galtz, J., Darvaši, P., Habala, I. The requirements on machinery safety and their influence on OHS effectiveness. Transport & Logistics: the International Journal, 2019; Volume 19, Issue 47, December 2019, ISSN 2406-1069 THE REQUIREMENTS ON MACHINERY SAFETY AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON OHS EFFECTIVENESS Hana Pacaiova 1, Juraj Glatz 1, Peter Darvaši 1, Ivan Habala 1 1 Technical University of Kosice, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Letna 9, 04200 Kosice, Slovakia, tel: +4210556022290, e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract: A legislative requirement that specifies the scope for occupational health and safety (OHS) and machinery safety has been implemented in the EU for 30 years. Basic condition for maintaining OHS is safely constructed and operated machinery / equipment. The obligation of constructors (producer, representative) is to launch only such machinery equipment which does not threaten health and safety of persons, domestic animals or property. The criterion for meeting these regulations is risk assessment. For maintenance activities, there are, in the EU directive on machinery safety (2006/42/ES), set requirements for the isolation of hazardous energy, which may threaten life or health of maintenance workers when performing the required activity. Identification process of this energy must be a part of risk assessment, the result of which is such a construction solution that enables disconnecting from all energy sources in a safe and convenient way together with its lockout. -

Situational Awareness, Workload, Preference Scheduling

Pre-print Version | To Appear in IJRR Special Issue on HRI in 2017 Journal Title XX(X):1–20 Computational Design of Mixed-Initiative c The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permission: Human-Robot Teaming that Considers sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/ToBeAssigned Human Factors: Situational Awareness, www.sagepub.com/ Workload, and Workflow Preferences Matthew Gombolay1, Anna Bair1, Cindy Huang1, and Julie Shah1 Abstract Advancements in robotic technology are making it increasingly possible to integrate robots into the human workspace in order to improve productivity and decrease worker strain resulting from the performance of repetitive, arduous physical tasks. While new computational methods have significantly enhanced the ability of people and robots to work flexibly together, there has been little study into the ways in which human factors influence the design of these computational techniques. In particular, collaboration with robots presents unique challenges related to preserving human situational awareness and optimizing workload allocation for human teammates while respecting their workflow preferences. We conducted a series of three human subject experiments to investigate these human factors, and provide design guidelines for the development of intelligent collaborative robots based on our results. Keywords Human-Robot Teaming, Human-Robot Interaction, Planning and Scheduling, Situational Awareness, Workload, Preference Scheduling Introduction not guarantee the long-term productivity and viability of the human-robot team. Human-robot teaming has the potential to increase the Researchers have shown that providing a machine or productivity of human labor and improve the ergonomics of robotic agent with autonomous capabilities yields important manual tasks. Based on recent industry interest in fielding benefits for human-robot team fluency (Dragan & Srinivasa human-robot teams, researchers have been investigating how 2012; Dragan et al. -

Citizens' Observatories for Situation Awareness in Flooding

Lanfranchi et al. Citizens' Observatories for Situation Awareness in Flooding Citizens' Observatories for Situation Awareness in Flooding Vitaveska Lanfranchi Stuart N. Wrigley University of Sheffield, UK University of Sheffield, UK [email protected] [email protected] Neil Ireson Fabio Ciravegna University of Sheffield, UK University of Sheffield, UK [email protected] [email protected] Uta Wehn UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education [email protected] ABSTRACT Citizens’ observatories are emerging as a means to establish interaction and co-participation between citizens and authorities during both emergencies and the day-to-day management of fundamental resources. In this paper we present a case study in which a model of citizens’ observatories is being been translated into practice in the WeSenseIt project. The WeSenseIt citizens’ observatory provides a unique way of engaging the public in the decision-making processes associated with water and flood management through a set of new digital technologies. The WeSenseIt citizens’ observatory model is being implemented in three case studies based in the UK, the Netherlands and Italy. We describe the findings and our experiences following preliminary evaluations of the technologies and the model of co-participation and describe our future research plans. Keywords Citizens’ observatory, water, flood, sensor, modelling, governance INTRODUCTION Climate change is expected to significantly affect water quality, water availability and flooding. Predictions indicate that over the next 70 years there will be a doubling in both the number of people affected by flooding each year (to 0.5-0.8 million) and in the annual damages (increasing to 7.7-15 billion €) (Ciscar, 2009). -

Interface Design for Sonobuoy Systems

Interface Design for Sonobuoy Systems by Huei-Yen Winnie Chen A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Applied Science in Systems Design Engineering Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2007 ©Huei-Yen Winnie Chen 2007 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract Modern sonar systems have greatly improved their sensor technology and processing techniques, but little effort has been put into display design for sonar data. The enormous amount of acoustic data presented by the traditional frequency versus time display can be overwhelming for a sonar operator to monitor and analyze. The recent emphasis placed on networked underwater warfare also requires the operator to create and maintain awareness of the overall tactical picture in order to improve overall effectiveness in communication and sharing of critical data. In addition to regular sonar tasks, sonobuoy system operators must manage the deployment of sonobuoys and ensure proper functioning of deployed sonobuoys. This thesis examines an application of the Ecological Interface Design framework in the interface design of a sonobuoy system on board a maritime patrol aircraft. Background research for this thesis includes a literature review, interviews with subject matter experts, and an analysis of the decision making process of sonar operators from an information processing perspective. A work domain analysis was carried out, which yielded a dual domain model: the domain of sonobuoy management and the domain of tactical situation awareness address the two different aspects of the operator's work. -

Frequency and Type of Situational Awareness Errors Contributing to Death and Brain Damage a Closed Claims Analysis

Frequency and Type of Situational Awareness Errors Contributing to Death and Brain Damage A Closed Claims Analysis Christian M. Schulz, M.D., Amanda Burden, M.D., Karen L. Posner, Ph.D., Shawn L. Mincer, M.S.W., Randolph Steadman, M.D., Klaus J. Wagner, M.D., Karen B. Domino, M.D., M.P.H. Perioperative Medicine ABSTRACT Background: Situational awareness errors may play an important role in the genesis of patient harm. The authors examined closed anesthesia malpractice claims for death or brain damage to determine the frequency and type of situational awareness errors. Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/127/2/326/488463/20170800_0-00024.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 Methods: Surgical and procedural anesthesia death and brain damage claims in the Anesthesia Closed Claims Project database were analyzed. Situational awareness error was defined as failure to perceive relevant clinical information, failure to comprehend the meaning of available information, or failure to project, anticipate, or plan. Patient and case characteristics, primary dam- aging events, and anesthesia payments in claims with situational awareness errors were compared to other death and brain damage claims from 2002 to 2013. Results: Anesthesiologist situational awareness errors contributed to death or brain damage in 198 of 266 claims (74%). Respiratory system damaging events were more common in claims with situational awareness errors (56%) than other claims (21%, P < 0.001). The most common specific respiratory events in error claims were inadequate oxygenation or ventilation (24%), difficult intubation (11%), and aspiration (10%). Payments were made in 85% of situational awareness error claims compared to 46% in other claims (P = 0.001), with no significant difference in payment size. -

Situation Awareness in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Their Relatives: an Endophenotype Study

370 Arch Neuropsychiatry 2018;55:370−375 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2017.20571 Situation Awareness in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Their Relatives: an Endophenotype Study Didem TEZCAN1 , Selim TÜMKAYA2 1İzzet Baysal Research and Training Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, Bolu, Turkey 2Pamukkale University Medicine Faculty, Department of Psychiatry, Denizli, Turkey ABSTRACT Introduction: It has been theorized that endophenotype models will patients with OCD and control group in both SA1 and SA2 tasks. help to understand the etiology of heterogeneous brain disorders such Patients with OCD performed significantly worse than control group on as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In this study, it was aimed to SA1 single and dual task. On the other hand, there were no significant determine whether “situational awareness” impairments which can differences between relatives and patients of any SA assessment. be defined as partially naturalistic working memory deficits, are an endofenotype for OCD. Conclusion: These results indicated that poor situational awareness may be a candidate endophenotype for OCD. Early perceptual dysfunctions Methods: In this study, situational awareness (SA) task performances of 67 OCD patients, 50 their unaffected first-degree relatives, and 41 such as poor performance on SA1 task can mediate the genetic risk for healthy controls who matched with regard to sex, age and years of OCD. education were measured to investigate endophenotypes in OCD. For Keywords: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, situation awareness, this purpose, a visuospatial working memory test was used. endophenotype, working memory, visuo-spatial working memory, Results: As a result, the relatives showed a task performance between neuropsychology Cite this article as: Tezcan D, Tümkaya S. -

A Review of Situation Awareness Assessment Approaches in Aviation Environments

IEEE SYSTEMS JOURNAL Digital Object Identifier 10.1109/JSYST.2019.2918283 https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8732669 A Review of Situation Awareness Assessment Approaches in Aviation Environments Thanh Nguyen, Chee Peng Lim, Ngoc Duy Nguyen, Lee Gordon-Brown, Saeid Nahavandi, Senior Member, IEEE Abstract—Situation awareness (SA) is an important which include decision-making, crew cooperation, and general constituent in human information processing and essential in systems management, are also important [7]. In this aspect, pilots’ decision-making processes. Acquiring and maintaining non-technical competencies related to SA and threat appropriate levels of SA is critical in aviation environments as it management play a vital role in the prevention of affects all decisions and actions taking place in flights and air accidents/incidents, such as CFIT and runway incursions [1]. traffic control. This paper provides an overview of recent measurement models and approaches to establishing and Therefore, numerous techniques have been proposed for enhancing SA in aviation environments. Many aspects of SA are monitoring and assessment of SA in pilot training and air traffic examined including the classification of SA techniques into six control, in order to improve pilot competency and increase categories, and different theoretical SA models from individual, to flight safety. shared or team, and to distributed or system levels. Quantitative In the aviation domain, crew resource management training and qualitative perspectives pertaining to SA methods and issues is now mandatory for increasing the safety of aviation of SA for unmanned vehicles are also addressed. Furthermore, operations. However, statistics indicate that 70% of air future research directions regarding SA assessment approaches accidents/incidents worldwide are the result of flight crew are raised to deal with shortcomings of the existing state-of-the-art actions [8]. -

Degraded Situation Awareness Risk Assessment in the Aerospace Domain Jean-Marc Salotti, Ephraïm Suhir

Degraded situation awareness risk assessment in the aerospace domain Jean-Marc Salotti, Ephraïm Suhir To cite this version: Jean-Marc Salotti, Ephraïm Suhir. Degraded situation awareness risk assessment in the aerospace domain. IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, Jun 2019, Torino, Italy. hal- 02162283 HAL Id: hal-02162283 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02162283 Submitted on 21 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Degraded situation awareness risk assessment in the aerospace domain Jean-Marc Salotti Ephraim Suhir 1: Portland State University, Depts. of Mech. and Mat., and 1: Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, Bordeaux INP, IMS, UMR 5218, F- Elect. and Comp. Engineering, Portland, OR, USA; 33400, Talence, France 2: Technical University, Dept. of Applied Electronic Materials, 2: INRIA, IMS, UMR 5218, F-33400, Talence, France Inst. of Sensors and Actuators, Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 3 :ERS Co., 727 Alvina Ct., Los Altos, CA 94024, USA, tel. 650.969.1530, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract—Numerous accidents are due to situation awareness point of view of human factors and situation awareness (SA) degradation. However, as there exist many different causes and degradation [3,5]. -

Cyber Situational Awareness Testing

Cyber Situational Awareness Testing B Joel Brynielsson1,2( ), Ulrik Franke3, and Stefan Varga2,4 1 FOI Swedish Defence Research Agency, 164 90 Stockholm, Sweden [email protected] 2 KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 100 44 Stockholm, Sweden 3 SICS Swedish Institute of Computer Science, Box 1263, 164 29 Kista, Sweden [email protected] 4 Swedish Armed Forces Headquarters, 107 85 Stockholm, Sweden [email protected] Abstract. In the cyber security landscape, the human ability to comprehend and adapt to existing and emerging threats is crucial. Not only technical solutions, but also the operator’s ability to grasp the complexities of the threats affect the level of success or failure that is achieved in cyber defence. In this paper we discuss the general concept of situation awareness and associated measurement techniques. Further, we describe the cyber domain and how it differs from other domains, and show how predictive knowledge can help improve cyber defence. We discuss how selected existing models and measurement techniques for situation awareness can be adapted and applied in the cyber domain to measure actual levels of cyber situation awareness. We identify generic relevant criteria and other factors to consider, and propose a methodol- ogy to set up cyber situation awareness measurement experiments within the context of simulated cyber defence exercises. Such experiments can be used to test the viability of different cyber solutions. A number of concrete possible experiments are also suggested. Keywords: Situational awareness · Measurement technique · Experimental design · Cyber defence exercise 1 Introduction In cyber security it is seldom straightforward to get a sense of the threat land- scape as a whole in order to really know “what is going on”1. -

30 Nov Hires Report

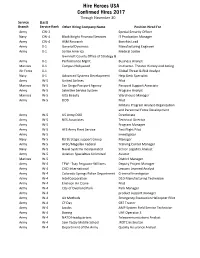

Hire Heroes USA Confirmed Hires 2017 Through November 30 Service (Last) Branch Service Rank Other Hiring Company Name Position Hired For Army CW-2 Special Security Officer Navy CW-4 Black Knight Financial Services IT Production Manager Army CW-4 ASM Research Benefits Lead Army 0-1 General Dynamics Manufacturing Engineer Army 0-1 Scribe America Medical Scribe Gwinnett County Office of Strategy & Army 0-1 Performance Mgmt. Business Analyst Marines 0-1 Campus Hollywood Instructor- Theater History and Acting Air Force 0-1 Global Threat & Risk Analyst Navy 0-1 Advanced Systems Development Help Desk Specialist Army W-5 United Airlines Pilot Marines W-5 San Diego Passport Agency Passport Support Associate Army W-5 Selective Service System Program Analyst Marines W-5 Ulta Beauty Warehouse Manager Army W-5 DOD Pilot Military Program Analyst-Organization and Personnel Force Development Army W-5 US Army DOD Directorate Army W-5 NES Associates Technical Director Army W-5 Program Manager Army W-5 AFS Army Fleet Service Test Flight Pilot Army W-5 Investigator Navy W-5 R3 Strategic support Group Manager Army W-5 AFSC/Magellan Federal Training Center Manager Navy W-5 Naval Systems Incorporated Senior Logistics Analyst Army W-5 Aviation Specialties Unlimited Aviator Marines W-5 District Manager Army W-4 TFW - Tsay Ferguson-Williams Deputy Project Manager Army W-4 CACI International Lessons Learned Analyst Army W-4 Colorado Springs Police Department Criminal Investigator Army W-4 Intel Corporation D1D Manufacturing Technician Army W-4 Erickson Air Crane -

Situation Awareness in Aircraft Maintenance Teams Mica R

International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 26 (2000) 301}325 Situation awareness in aircraft maintenance teams Mica R. Endsley! *, Michelle M. Robertson" !SA Technologies, 4731 East Forest Peak, Marietta, GA 30066, USA "Liberty Mutual Research Center, Hopkinton, MA 01748, USA Accepted 15 June 1998 Abstract Research was conducted at a major airline to investigate factors related to situation awareness in aviation maintenance teams. Situation awareness has been found to be critical to performance and error prevention in many environments. Its role in the maintenance domain for the performance of both individuals and teams is discussed. Situation awareness requirements for aviation maintenance were determined as well as the technologies and personnel resources used to achieve situation awareness. Barriers and problems for situation awareness both across and within teams involved in aviation maintenance were revealed. Based on this analysis, recommendations for the development of a training program to improve situation awareness in aircraft maintenance at the individual and team level are presented. Relevance to industry The importance of situation awareness for preventing errors in maintenance is discussed as well as factors that contribute to problems with situation awareness across multiple teams. Speci"c recommendations for improving situation awareness through organization and system design and through training are made that are applicable to a wide variety of industrial settings. ( 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Situation awareness; Teams; Maintenance; Training; Error 1. Introduction (1994), for instance, report that 12% of accidents are due to maintenance and inspection faults, and Insu$cient attention has been paid to human around one-third of all malfunctions can be at- error in aircraft maintenance.