Early Efforts at Socialist Unity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “New Yorker Volkszeitung.” {1}

VOL. VIII, NO. 39 NEW YORK, SUNDAY, DECEMBER 25, 1898 PRICE 2 CENTS POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC The “New Yorker Volkszeitung.” {1} By DANIEL DE LEON he New Yorker Volkszeitung of the 14th instant, commenting upon the honest and the dishonest elements at the so-called convention of the so-called American T Federation of Labor, proceeds to say: The comfort of these two elements was formerly not quite so well provided for at the time when there were more Socialist pikes in that pond; at the time, namely, when a part of these had not yet chosen to lead, outside of the American Federation, a separate existence of doubtful success, instead of, as formerly, tirelessly, unflaggingly, step by step, boring their way forward from within. At that time, the corruptionists of the Labor Movement always felt quite uncomfortable at the opening of every annual convention, because they were in the dark as to the strength in which the Socialists might turn up, as to the weapons of attack these might be equipped with, and as to how far these would succeed in making breaches in the ranks of the shaky. This sense of uneasiness is now wholly vanished. The theory here advanced, together with the implied facts that are needed to support it, is a pure figment of the brain,—the abortion of a convenient ignorance on the history of the Movement in America, coupled with that queer “tactfulness” that consists in flinging about phrase-clad pretexts to justify indolence. It is a surreptitious re-asserting of tactics that the party, in national convention assembled in ’96, solemnly threw aside for ever as stupid and poltroonish. -

Connolly in America: the Political Development of an Irish Marxist As Seen from His Writings and His Involvement with the American Socialist Movement 1902-1910

THESIS UNIVERSITY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES CONNOLLY IN AMERICA: THE POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT OF AN IRISH MARXIST AS SEEN FROM HIS WRITINGS AND HIS INVOLVEMENT WITH THE AMERICAN SOCIALIST MOVEMENT 1902-1910 by MICHEÁL MANUS O’RIORDAN MASTER OF ARTS 1971 A 2009 INTRODUCTION I have been most fortunate in life as regards both educational opportunities and career choice. I say this as a preface to explaining how I came to be a student in the USA 1969-1971, and a student not only of the history of James Connolly’s life in the New World a century ago, but also a witness of, and participant in, some of the most momentous developments in the living history of the US anti-war and social and labour movements of 40 years ago. I was born on Dublin’s South Circular Road in May 1949, to Kay Keohane [1910-1991] and her husband Micheál O’Riordan [1917- 2006], an ITGWU bus worker. This was an era that preceded not only free third-level education, but free second-level education as well. My primary education was received in St. Kevin’s National School, Grantham Street, and Christian Brothers’ School, Synge Street. Driven to study - and not always willingly! - by a mother who passionately believed in the principle expounded by Young Irelander Thomas Davis – “Educate, that you may be free!” - I was fortunate enough to achieve exam success in 1961 in winning a Dublin Corporation secondary school scholarship. By covering my fees, this enabled me to continue with second-level education at Synge Street. In my 1966 Leaving Certificate exams I was also fortunate to win a Dublin Corporation university scholarship. -

Socialist Labor Party: 1906-1930 (Pdf)

SSOOCCIIAALLIISSTT LLAABBOORR PPAARRTTYY:: 11990066 ––11993300 A 40TH ANNIVERSARY SKETCH OF ITS EARLY HISTORY By Olive M. Johnson OLIVE M. JOHNSON (1872–1954) [EDITOR’S NOTE: For purposes of continuity, it is recommended that Henry Kuhn’s sketch of SLP history from 1890 to 1906 be read first.] EITHER the grilling financial struggle nor even the conspiracies and treacheries tell the whole tale of the Party’s history during the decade from NN1895 to 1905. The really important thing is that in the crucible of struggle its principles and policies and with it the principles and policies of the revolutionary movement of America were cast and clarified. De Leon himself grew in stature and conception during these trying years. It is necessary here to review the situation. Party Policy Clarified. Long before 1905 De Leon, and with him the Socialist Labor Party, had perceived that the policy known as “boring from within” the labor unions would never accomplish its aim of turning the members of the “pure and simple” faker-led American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) into classconscious Socialists. The most active members in fact were “boring themselves out.” At the same time it was becoming ever clearer to the S.L.P. that the political movement of the workers must have “an economic foundation.” This foundation, of course, pointed directly to the shop and factory; but the shop and factory were either left entirely unorganized or in the hands of the A.F. of L., which, as was becoming increasingly clearer, while an organization of workers, was officered by “lieutenants” of the capitalists, hence just as much a capitalist organization as the German army was a ruling class Socialist Labor Party 1 www.slp.org Olive M. -

Vulgar Economy

Vulgar Economy Or a Critical Analyst of Marx Analyzed By DANIEL DE LEON Published Online by Socialist Labor Party of America www.slp.org August 2002 Vulgar Economy Or a Critical Analyst of Marx Analyzed By DANIEL DE LEON “Once for all I may here state, that by classical political economy, I understand that economy, which, since the time of W. Petty, has investigated the real relations of production in bourgeois society, in contradistinction to vulgar economy, which deals with appearances only, ruminates without ceasing on the materials long since provided by scientific economy, and there seeks plausible explanations of the most obtrusive phenomena, for bourgeois daily use, but for the rest, confines itself to systematizing in a pedantic way, and proclaiming for everlasting truths, the trite ideas held by the self-complacent bourgeoisie with regard to their own world, to them the best of all possible worlds.” —Marx.1 PUBLISHING HISTORY PRINTED EDITION ...................................... October 1914 ONLINE EDITION ......................................... August 2002 NEW YORK LABOR NEWS P.O. BOX 218 MOUNTAIN VIEW, CA 94042-0218 http://www.slp.org/nyln.htm 1 Capital, p. 53. PREFACE. In sending out in book form this work by Daniel De Leon, which is the first published since his death, a few remarks on the author and the subject treated might not be amiss. The pamphlet is made up of a series of articles which appeared in the Daily People from April 8 to June 29, 1912, and should have been concluded by an “Epilogue.” For some reason De Leon did not finish this chapter, and the notes left are not complete, and what there is, is hardly legible.1 Daniel De Leon was born on December 14, 1852, on the island of Curaçao, off the coast of Venezuela. -

A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28 Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 20

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 2017 The Westin Copley Place 10 Huntington Avenue Boston, MA 02116 Conference Director: Olivia Carr Edenfield Georgia Southern University American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 28th Annual Conference on American Literature May 25 – 28, 2017 Acknowledgements: The Conference Director, along with the Executive Board of the ALA, wishes to thank all of the society representatives and panelists for their contributions to the conference. Special appreciation to those good sports who good-heartedly agreed to chair sessions. The American Literature Association expresses its gratitude to Georgia Southern University and its Department of Literature and Philosophy for its consistent support. We are grateful to Rebecca Malott, Administrative Assistant for the Department of Literature and Philosophy at Georgia Southern University, for her patient assistance throughout the year. Particular thanks go once again to Georgia Southern University alumna Megan Flanery for her assistance with the program. We are indebted to Molly J. Donehoo, ALA Executive Assistant, for her wise council and careful oversight of countless details. The Association remains grateful for our webmaster, Rene H. Treviño, California State University, Long Beach, and thank him for his timely service. I speak for all attendees when I express my sincerest appreciation to Alfred Bendixen, Princeton University, Founder and Executive Director of the American Literature Association, for his 28 years of devoted service. We offer thanks as well to ALA Executive Coordinators James Nagel, University of Georgia, and Gloria Cronin, Brigham Young University. -

A HISTORY of the GREAT WAR APRIL, 1915 Ten Cents

A HISTORY OF THE GREAT WAR APRIL, 1915 Ten Cents Do you want a history of the Great War in its larger social and revolutionary aspects? Interpreted by the foremost Socialist thinkers? The following FIVE issues of the NEW REVIEW consti- tute the most brilliant history extant: evew FEBRUARY, 1915, ISSUE "A _New International," by Anton Pannekoek; "Light and Shade of the Great War," by H. M. Hyndman; "Against the 'Armed Nation' or 'Citizen Army,' " by F. A CRITICAL SURVEY OF INTERNATIONAL SOCIALISM M. Wibaut, of Holland; "The Remedy for War: Anti-Nationalism," by William Eng- lish Walling; "A Defense of the German Socialists," by Thomas C. Hall, D.D.; the SOCIALIST DIGEST contains: Kautsky's "Defense of the International;" "A Criti- cism of Kautsky:" A. M. Simons' attack on the proposed Socialist party peace pro- gram; "Bourgeois Pacifism;" "A Split Coming in Switzerland?" "Proposed Peace Program of the American Socialist Party;" "Messages from Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemberg," etc. THE BERNHARDI SCHOOL JANUARY, 1915, ISSUE "A Call for a New International;" "Capitalism, Foreign Markets and War," by Isaac A. Hourwich; "The Future of Socialism," by Louis^ C. Fraina; "As to Making OF SOCIALISM Peace," by Charles Edward Russell; "The Inner Situation in Russia," 677 Paul Axelrod; "Theory, Reality and the War," by Wm. C. Owen; the SOCIALIST DIGEST contains: "Kautsky's New Doctrine," "Marx and Engels Not Pacifists," by Eduard Bernstein; "An American Socialist Party Resolution Against Militarism;" "The International By Isaac A. Hourwick Socialist Peace Congress;" "A Disciplining of Liebknecht?" "German Socialists and the War Loans;" "Militarism and State Socialism," etc. -

November 1926

USSIA ROMANCE OF NEW III/ Xc RUSSIA Magdeleine Marx RUSSIA TURNS EAST The impressions made by MOHIUIY Soviet Russia on this famous By Scott Nearing French novelist will make interesting reading for any A brief account of what worker. A beautiful book. Russia is doing in Asia. $ .10 Cloth bound—$2.00 BROKEN EARTH —THE GLIMPSES OF RUSSIAN VILLAGE THE SOVIET REPUBILC TODAY By Scott Nearing By Maurice Hindus A bird's-e.ve view of Rus- A well-known American sia in impressions of the au- journalist and lecturer, re- thor on his recent visit. visits in this book the small Russian village of his birth. $ .10 His frank narrative reveals the Russian peasant as he is today, growing to new stat- EDUCATION IN ure and consciousness in a new society. SOVIET RUSSIA Cloth bound—$2.00 Scott Nearing A tinu-lmnd account o f A MOSCOW DIARY aims and methods of educa- By Anna Porter tion in the Soviet republics. A series of vivid new im- Cloth bound—$1.50 pression of life in the world's Paper-— .50 first workers' government. Cloth—$1.00 COMMERCIAL HAND- MARRIAGE LAWS OF BOOK OF THE U. S. S. R. SOVIET RUSSIA A new brief i-ompendiuni The Soviet marital code is of information on the So- an innovation in laws that is viet Union. Interesting and of great historic movement. .if value for all purposes. $ .10 $ .25 THE NEW THEATER AND CINEMA Or SOVIET This Book Stilt Remains the RUSSIA By Huntley Carter LENIN Most Complete Report on .Mr. Carter, the eminent author- ity, presents here a veritable ency- LENIN—The Great Strategist, clopedia of the Russian theater to- By A. -

History of the American Socialist Youth Movement to 1929. by Shirley Waller

Waller: History of the American Socialist Youth Movement [c. 1946] 1 History of the American Socialist Youth Movement to 1929. by Shirley Waller This material was irst published as part of two bulletins prepared circa 1946 for the Provisional National Committee for a Socialist Youth League [Youth Section of the Workers Party]. Subsequently reprinted with additional introductory and summary material by Tim Wohlforth as History of the International Socialist Youth Movement to 1929, published as a mimeographed “Educational Bulletin No. 3” by The Young Socialist [Socialist Workers Party], New York, n.d. [1959]. * * * Department organized Socialist Sunday Schools for the purpose of training children from the ages of 6 to The Socialist Party of America. 14, at which time they were ready to enter the YPSL. A book published by David Greenberg, Socialist Sun- In 1907 young people’s groups were organized day School Curriculum, is particularly interesting in on a local scale by the Socialist Party which started out showing the methods employed in the training of as purely educational groups studying the elements of younger children. In the primary class, children of 6 socialist theory. The 1912 convention of the Socialist and 7 studied economics. The purpose was “to get the Party recognized the fact that the spontaneous and children to see that the source of all things is the earth uncoordinated growth of the Socialist youth move- which belongs to everybody and that it is labor that ment was in itself sufficient proof of the need of such takes everything from the earth and turns it (1) into a movement on an organized basis. -

Making Ready for the Third Act

VOL. 6, NO. 177. NEW YORK, SUNDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1905. TWO CENTS. EDITORIAL MAKING READY FOR THE THIRD ACT. By DANIEL DE LEON N the 3rd of this month the New Yorker Volkszeitung published a call, or manifesto, for the organization of a “Socialist League” of the Volkszeitung OO Corporation’s Germans, euphoniously termed “the German Social Democrats” of America. The call opens with an attempt to account for the recent decline in the Socialist party vote by negligent agitation “among the Germans”. That this expression is not an unintentional slip appears from the argument that follows, and which confirms the hint, thrown out in this initial expression, to the effect that the Volkszeitung Corporation Germans are THE thing, and the only reliable thing. The call then proceeds to declare that the said “German Social Democrats” of the country are the “trunk” of the Socialist Movement here in America; that they are the “backbone” of the Movement; that, it pointedly implies, they are the beacons of that “idealism” without which there can be no true Socialism; that that necessary idealism “finds no good soil here”; and that, for all these reasons, theirs is the duty to educate, to train the “English speaking” element of the land, in short, “to point the way” to this element—presumably towards “idealism” and the other qualities that go to make “trunks” and “backbone”. What the “ideal” is that the callers of the call pursue and would “point the way” to, and what they are the “trunk” and “backbone” of was speedily made clear by the editorial article that the call was followed up with in the issue of the Volkszeitung of the following 19th of this same month. -

The Downfall of Barnes

VOL. 12, NO. 48. NEW YORK, THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1911. O N E C EN T. EDITORIAL THE DOWNFALL OF BARNES. By DANIEL DE LEON T is not as “the latest instance of Socialist party corruption” that we stop this day to contemplate the resignation from his office, under charges, by J. II Mahlon Barnes, the National Secretary of the Socialist party, as previously reported by special correspondence from Chicago. For one thing, the instances. of corrupt conduct on the part of S.P. officials have been documentarily cited in these columns with such profusion that, in view of the many other important events of the day, this particular one could be ignored. For another thing, however strenuous the efforts of the S.P. privately owned press to suppress the facts in the case, the efforts will prove futile. The facts are so scandalous—the debauchery they reveal is so outré, the graft so tell-tale—that their very fumes will raise the lid, and keep it raised. The downfall of Mr. Barnes preaches a sermon of singular import. Though a blot upon mankind, especially upon the Socialist Movement, Mr. Barnes might have held his post indefinitely. He buttressed too many kindred “In- terests” among his party’s officialdom to be easily assailable; and they, in turn, but- tressed up him. His own downfall would mean, at least, the insecurity of his fellows, if not their downfall also. Yet he fell. What caused the catastrophe? To say, as our Chicago special correspondence indicates, that the Jane Keep affidavit did it, is to miss the point. -

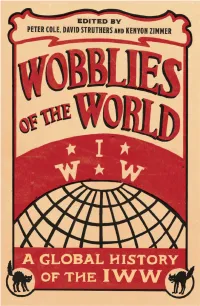

Wobblies of the World: a Global History of The

WOBBLIES OF THE WORLD i Wildcat: Workers’ Movements and Global Capitalism Series Editors: Peter Alexander (University of Johannesburg) Immanuel Ness (City University of New York) Tim Pringle (SOAS, University of London) Malehoko Tshoaedi (University of Pretoria) Workers’ movements are a common and recurring feature in contemporary capitalism. The same militancy that inspired the mass labour movements of the twentieth century continues to define worker struggles that proliferate throughout the world today. For more than a century labour unions have mobilised to represent the political- economic interests of workers by uncovering the abuses of capitalism, establishing wage standards, improving oppressive working conditions, and bargaining with em- ployers and the state. Since the 1970s, organised labour has declined in size and influ- ence as the global power and influence of capital has expanded dramatically. The world over, existing unions are in a condition of fracture and turbulence in response to ne- oliberalism, financialisation, and the reappearance of rapacious forms of imperialism. New and modernised unions are adapting to conditions and creating class-conscious workers’ movement rooted in militancy and solidarity. Ironically, while the power of organised labour contracts, working-class militancy and resistance persists and is growing in the Global South. Wildcat publishes ambitious and innovative works on the history and political econ- omy of workers’ movements and is a forum for debate on pivotal movements and la- bour struggles. The series applies a broad definition of the labour movement to include workers in and out of unions, and seeks works that examine proletarianisation and class formation; mass production; gender, affective and reproductive labour; imperialism and workers; syndicalism and independent unions, and labour and Leftist social and political movements. -

By Alexander Jonas †

Jonas: How I Became a Socialist [published 1912] 1 How I Became a Socialist: An Episode of My Boyhood. by Alexander Jonas † Published in The Young Socialists’ Magazine (New York), v. 5, no. 3 (March 1912), pp. 5-6. I shall never forget that wonderful spring of Again the blood of workingmen and women had been 1848. As the first warm breaths of air were wafted over shed for freedom. And in the midst of this great stir Europe the hearts of the people of all na- and confusion the bomb burst in my home city, tions were opened. It seemed as if they, Berlin, where the bloody revolt of the 18th too, like the snow and ice of the win- and 19th days of March, 1848, culminated ter, were being melted out of their in a complete victory of the people. stony despair. As small brooks were I understood but little of all this tur- changed overnight into roaring moil. Only 12 years of age, carefully torrents which, feeding the great reared in the protecting walls of a com- rivers, caused them to break down paratively comfortable home, I had be- every resistance and flood the land, come penetrated with the bourgeois ide- so did this sudden awakening of als and prejudices of the times. However, the European people swell and my father was not narrow-minded and broaden the great revolutionary had implanted into the hearts of his chil- movement. dren a strong love for liberty, a passionate From Lisbon to St. Petersburg the hatred against tyranny and oppression.