University of Derby Programme Code: PX3AA Module Code: 8EUXXX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

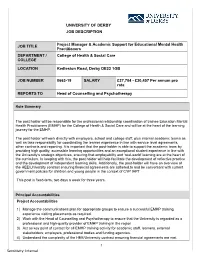

Internal UNIVERSITY of DERBY JOB DESCRIPTION JOB TITLE Project

UNIVERSITY OF DERBY JOB DESCRIPTION Project Manager & Academic Support for Educational Mental Health JOB TITLE Practitioners DEPARTMENT / College of Health & Social Care COLLEGE LOCATION Kedleston Road, Derby DE22 1GB JOB NUMBER 0663-19 SALARY £27,704 - £30,457 Per annum pro rata REPORTS TO Head of Counselling and Psychotherapy Role Summary The post holder will be responsible for the professional relationship coordination of trainee Education Mental Health Practitioners (EMHP) for the College of Health & Social Care and will be at the heart of the learning journey for the EMHP. The post holder will work directly with employers, school and college staff, plus internal academic teams as well as take responsibility for coordinating the learner experience in line with service level agreements, other contracts and reporting. It is important that the post-holder is able to support the academic team by providing high quality, accessible learning opportunities and an exceptional student experience in line with the University’s strategic objectives, ensuring that employability and ‘real-world’ learning are at the heart of the curriculum. In keeping with this, the post holder will help facilitate the development of reflective practice and the development of independent learning skills. Additionally, the post-holder will have an overview of the HEE/University contract ensuring financial agreements are adhered.to and be conversant with current government policies for children and young people in the context of CYP IAPT. This post is fixed-term, two days a week for three years. Principal Accountabilities Project Accountabilities 1) Manage the communications plan for appropriate groups to ensure a successful EMHP training experience visiting placements as required. -

Student Protection Plan

Nottingham Trent University Student Protection Plan UKPRN: 10004797 Legal Address: 50 Shakespeare Street, Nottingham, NG1 4FQ, UK Contact Point for Enquires about this Plan: Deputy Vice Chancellor (Academic Development and Performance) Student Protection Plan for 2020/21 academic year: Nottingham Trent University 1. Scope and identification of Risks Introduction: In accordance with the requirements of the Higher Education and Research Act 2017, this plan inform students of what they can expect should a course, campus or institution close. This Student Protection Plan (hereafter “the Plan”) aims to demonstrate that Nottingham Trent University (NTU) has considered how students can continue or complete their studies or be compensated if this is not possible. The University recognises that in the event of a significant course or campus closure it will be expected to work closely with the Office for Students and its own student body to ensure that students’ interests are protected through any such change. Nottingham Trent University is a large, established, high performing and financially stable provider. We would like to reassure both our students and applicants that the risks outlined in this Plan are all very low and in the case of closure extremely low. Examples of risks to which this Plan would apply: • Loss or restriction of University status or its degree awarding powers or its designation for student support or student intake; • Decision to close the institution, a campus or a specialist facility; • Long term disruption to your course -

NTU SPORT Fixtures: 04 – 10 February 2019

NTU SPORT Fixtures: 04 – 10 February 2019 Mon Equestrian C10 University of Lincoln A Riseholme College Equine Centre Championship Wed Badminton M1 Glasgow University 1 LWSC Main Hall B Wed Badminton W1 Loughborough University 3 Loughborough University Wed Basketball M1 Sheffield Hallam University 1 LWSC Main Hall A Wed Basketball M3 Anglia Ruskin University 3 LWSC Main Hall A Wed Basketball W2 University of Lincoln 1 University of Lincoln Sports Centre Wed Fencing M1 University of Leicester 2 Charles Wilson Sports Hall Wed Fencing W1 University of Cambridge 2 University of Cambridge Sports Centre Wed Football M2 University of Warwick 1 Clifton Campus (3G) Wed Football M3 University of Leicester 2 Forest Sport Zone 3G Wed Football M4 University of Derby 2 3G, Gresham Sports Park Wed Football W1 Northumbria University 2 Clifton Campus Pitch 4 Wed Football W2 University of Nottingham 2 Highfields Playing Fields Wed Football W3 Oxford University 2 Marston Sports Ground Wed Golf Mixed 1 University of Leicester Mixed 2 Ruddington Grange Golf Club Wed Hockey M1 University of Birmingham 1 Clifton Campus (Hockey Pitch) Wed Hockey M3 University of Cambridge 2 Clifton Campus (Hockey Pitch) Wed Hockey M4 University of Nottingham 5 David Ross Sports Village Wed Hockey W1 University of Sheffield 1 Norton Playing Fields Wed Hockey W2 University of Lincoln 1 Clifton Campus (Hockey Pitch) Wed Hockey W3 University of Derby 1 Clifton Campus (Hockey Pitch) NTU SPORT Fixtures: 04 – 10 February 2019 Wed Hockey W5 De Montfort University 1 St Margarets Pastures -

University of Derby Online Research Archive

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UDORA - University of Derby Online Research Archive University of Derby The Rise and Demise of the 14-19 Diploma Lynn Senior Doctor of Education August 2015 Abstract The Rise and Demise of the 14-19 Diploma Lynn Senior The introduction of the 14-19 Diploma into the English Qualifications framework was the most developed attempt at creating a vocational qualification which advanced beyond mere job training. The Diploma offered vocational education with occupational capacity, underpinned by functional skills and academic subject content. It was truly the first hybrid qualification that attempted to combine the hitherto separate vocational and academic curricula. This study examines the educational policies that led to the introduction of the Diploma and the reasons behind its ultimate failure and demise. The study comprises two parts. The first is an investigation into the continuing professional development needs that this new initiative created for teachers. This led to the publication in 2010 of a book, The Essential Guide to Teaching 14-19 Diplomas, a description and account of which is presented in this thesis. This book was the first of its kind aimed at supporting teachers working with the Diploma. The key research findings addressed were the need to understand the structure and constituent elements of the Diploma and to provide practical advice on how to deliver effective Initial Advice and Guidance (IAG), Personal Thinking and Learning Skills (PTLS) and Functional Skills. The second part of the study is concerned with the aftermath of the Diploma. -

The Derby Experience a Guide for Students Based at the Royal Derby Hospital Centre

The Derby experience A guide for students based at the Royal Derby Hospital Centre For undergraduate enquiries contact: Student Recruitment Enquiries Centre +44 (0)115 951 5559 nottingham.ac.uk/enquire UniofNottingham @UniofNottingham nottingham.ac.uk nottingham.ac.uk Contents Welcome Welcome 3 The University of Nottingham’s Royal City highlights 4 Derby Hospital Centre, based on the Student life 6 site of the Royal Derby Hospital, is fully Discover your perfect home 8 equipped with academic, social and Support services 10 administrative facilities. It’s home to Academic and administrative facilities 11 some of the courses and research groups Transport networks 12 from the Faculty of Medicine and Health Useful contacts 14 Sciences. The centre’s location, on the site of a busy and modern UniofNottingham hospital, is a fitting focus for healthcare and medical students. As a student based at the Derby site, you’ll UniofNottingham have the opportunity to join in with activities and events, many of which are organised by the students themselves. It’s a friendly, enthusiastic community that caters for students of all ages and backgrounds, and is complemented by easy access to a lively city and beautiful countryside. Derby is the most central city in England with excellent transport links. Derby is close to the M1, East Midlands Airport and is on a direct train line to London St Pancras. There is a free hopper bus from the Royal Derby Hospital Centre to University Park Campus, giving you the option of living in Derby or Nottingham. Find out more: 2 nottingham.ac.uk/studywithus/derby 3 City centre entertainment For film fans, there City is a 12 screen 4K cinema in Intu Derby. -

University of Derby

Knowledge that counts: an examination of the theory practice gap between business and marketing academics and business practitioners examined in respect of their respective epistemic stances Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Ash, Malcolm Publisher University of Derby Download date 25/09/2021 15:36:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/333867 UNIVERSITY OF DERBY KNOWLEDGE THAT COUNTS: AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY PRACTICE GAP BETWEEN BUSINESS AND MARKETING ACADEMICS AND BUISNESS PRACTITIONERS EXAMINED IN TERMS OF THEIR RESPECTIVE EPISTEMIC STANCES. Malcolm R Ash Programme Title Year Doctor of Education 2014 Acknowledgements My grateful and heartfelt thanks to my wife whose support has been so essential and without whose inspiration this would never have been finished. And to my supervisor David Longbottom whose wise and sound advice has been irreplaceable. Abstract Abstract This work examines and presents evidence for the existence of a gap in epistemological views between academic and practice marketers. Few if any academics would seem to challenge the ‘gap’ premise but the importance of any gap and its nature are issues about which little agreement exists. The intractable nature of the academic practitioner gap has a long history of interesting and diverse debate ranging from Dewey’s argument about the true nature of knowing to contributions based on epistemic adolescence, ontological differences and more pragmatic suggestions about different tribes. Others include the rigour versus relevance issue, failures in curriculum or pedagogy and a clash between modernist and postmodernist epistemologies. Polanyi’s description of tacit versus explicit knowledge further extends the debate as do issues of knowledge creation and dissemination in particular through Nonaka. -

Privacy Notice High Level Skills for Smes – ESF Funded Programmes

Nottingham Trent University – Privacy Notice High Level Skills for SMEs – ESF Funded Programmes Introduction Your privacy and protection of your personal information is very important to us and we are committed to robust compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (“UK GDPR”) and the Data Protection Act 2018. This privacy notice explains what Nottingham Trent University (“NTU”, “we”, “us” or “our”) does with your personal information, your rights and how we protect it. This notice is for all individuals (“you” or “your”) involved in one of the four ESF High Level Skills Projects. The ESF High Level Skills Programme consists of four European Social Fund funded projects, delivered in partnership with the Department for Work and Pensions and a consortium of partners, of which Nottingham Trent University is the Lead Partner. The Projects are primarily for small and medium-sized businesses in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire who want to benefit from expertise to improve employment opportunities, strengthen social inclusion, fight poverty, promote education, skills and life-long learning and develop active, comprehensive and sustainable inclusion policies and thereby contribute to economic, social and territorial cohesion. For more information about the High Level Skills Programme and the support available to businesses from NTU, visit our website. The four ESF High Level Skills Projects are: Priority Skills for D2N2 SMEs (Project Number: 08S17P0047), we work in collaboration with the following Partners: University of Derby Nottingham -

Enabling Innovation

Enabling Innovation Enabling Innovation is a three year collaborative programme involving Nottingham Trent University, the University of Derby and the University of Nottingham, which will provide support to over 2,000 local small and medium enterprises (SMEs) over three years. Focusing on ‘enabling technologies’, it aims to stimulate an innovation ecosystem designed to commercialise cutting edge R&D, support product and process innovation within SMEs and drive innovation through supply chains. Enabling Innovation is one of some 50 projects which the D2N2 LEP has supported with European funding. *This funding is secured and the programme will be unaffected by Brexit* Who is it for? Enabling Innovation is for small and medium-sized businesses in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire who want to benefit from university expertise in research and innovation to develop and grow their business. What is on offer? In-depth support for businesses in sectors such as manufacturing, materials engineering, computing and data, aerospace, food and drink, chemistry and satellite navigation – offering unprecedented access to university expertise and graduate talent. Workshop programmes designed to help businesses to innovate, explore new ideas and unlock their growth potential. Leadership and management development, including mentoring. Support for businesses to take on graduates via placement opportunities, allowing them to explore the benefits of employing graduates. Is it right for you? Browse through the list of services on offer from an extensive range of expertise resident in the three midlands based universities – see list at end. What will it cost? We have secured European Union funding which means that most services provided as part of the Enabling Innovation programme are free of charge to qualifying businesses. -

ICMR2020 CHAIR : Andrew Thomas, Aberystwyth University VICE CHAIR: Fayyaz Rehman, Southampton Solent University

GENERAL CHAIR: Warren Manning PROGRAM CHAIR: Mahmoud Shafik ORGANIZING COMMITTEE CHAIR: Louise Pigden THE CONSORTIUM OF UK UNIVERSITY MANUFACTURING AND ENGINEERING (COMEH) ADVISORY COMMITTEE CHAIR: Andrew Thomas, Aberystwyth University ICMR2020 VICE CHAIR: Fayyaz Rehman, Southampton Solent University 18TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON TREASURER: Peter Ball, University of York SECRETARY: Yi Qin, Strathclyde University MANUFACTURING RESEARCH Linda Newnes, University of Bath Keith Case, Loughborough University 8 – 10 September 2020 Tim Baines, Aston University Kai Cheng, Brunel University Alan Crispin, Manchester Metropolitan University University of Derby, Derby, UK James Gao, University of Greenwich Yee Mey Goh, Loughborough University Conference Website: www.icmr.org.uk David Harrison, Glasgow Caledonian University Mehmet Karamanoglu, Middlesex University Diane Mynors, University of Sussex Sameh Saad, Sheffield Hallam University Mozafar Saadat, University of Birmingham Essam Shehab, Cranfield University Aydin Nassehi, University of Bristol Remy Khalil, Homeodynamic Autonomy Limited Mahmoud Shafik, University of Derby Yan Jin, Queen’s University Belfast Weidong Li, Coventry University Konstantinos Salonitis, Cranfield University University of Derby Main Headquarter: https://jobs.derby.ac.uk/ www.icmr.org.uk Sensitivity: Internal INTRODUCTION: PAPER SUBMISSIONS: The International Conference on Manufacturing Research (ICMR2020) will take place from Contributions are invited from researchers and practitioners working in the field of 8th until 10th of September 2020 at the University of Derby, Derby, UK. It will include keynote product development, manufacturing and product service engineering. Full paper should presentations by internationally renowned researchers and industrialists, as well as papers be submitted via Easychair (https://easychair.org/cfp/ICMR2020) Please follow the from academia and industry, exploring all core areas of advanced and digital manufacturing instructions strictly and use the template provided. -

Submission Guidance for Authors

Research, Policy and Planning The Journal of the Social Services Research Group Editors: Guy Daly, University of Derby John Woolham, Coventry University ([email protected] ) ([email protected] ) Publishing Editor: Shelley Nix University of Derby Britannia Mill Mackworth Road Derby DE22 3BL Tel: 01332 594068 Email: [email protected] Guidelines for authors Research, Policy and Planning is a peer reviewed journal published three times a year. It is devoted to publishing research by researchers and practitioners in local and central government, other statutory bodies and voluntary agencies and academic institutions which bears on the interests and concerns of SSRG members. For editorial purposes, research is taken to include empirical studies, policy analyses, planning reports, literature surveys and review articles. Descriptive accounts and case studies may be published as a Short Report after discussion with the editors. Submission guidance Papers should be no more than 5000 words, excluding abstract, references and tables. They should be double-spaced throughout, allowing good margins. Where possible, manuscripts for consideration should be submitted in electronic form to Shelley Nix ([email protected] ). Alternatively manuscripts can be submitted by post as hard copy or on disk. All pages of the manuscript should be numbered consecutively, beginning with the title page. The format for submission is: Title page A separate title page should be provided. This should include the title of the paper, author(s) name(s) and affiliation, a brief biographical note and the corresponding author’s contact details. Abstract and keywords This should be no more than 200 words and should outline the purpose of the study, methods, main findings and implications for policy and practice. -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Liyanage, Lalith (2013) A case study of the effectiveness of the delivery of work based learning from the perspective of stakeholders in Computing, Engineering and Information Sciences at Northumbria University. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/21418/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html A CASE STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE DELIVERY OF WORK BASED LEARNING FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF STAKEHOLDERS IN COMPUTING, ENGINEERING AND INFORMATION SCIENCES AT NORTHUMBRIA UNIVERSITY LALITH LIYANAGE PhD 2013 1 A CASE STUDY OF THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE DELIVERY OF WORK BASED LEARNING FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF STAKEHOLDERS IN COMPUTING, ENGINEERING AND INFORMATION SCIENCES AT NORTHUMBRIA UNIVERSITY LALITH LIYANAGE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in Faculty of Engineering and Environment April 2013 2 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. -

The University of Derby Leverages End-User Context to Provide Leading- Edge IT Services

NEXTHINK SUCCESS STORY The University of Derby Leverages End-User Context to Provide Leading- Edge IT Services ORGANIZATION The University of Derby selected Nexthink to uncover critical data relationships and The University of Derby enhance the learning experience. Nexthink endpoint and end-user IT analytics drives both current success and helps the University prepare for future service innovations. INDUSTRY Education CONTEXT LOCATION Achieving university status in 1992, the University of Derby has earned both UK national and global accolades thanks to its investment in world class facilities and reputation for student-focused real world learning. As the only university in KEY CHALLENGES the county of Derbyshire, the University now serves more than 30,000 students. z Enhance the learning experience through a robust and scalable IT infrastructure to support learning empowered technology and manage future growth z Need to uncover critical data relationships and provide essential end-user context when making strategic business decisions z Efficiently support students and staff by quickly accessing relevant contextual endpoint and end- user data To empower current students and engage the next generation of learners, the University of Derby embraces the values of quality, value, customer focus, chal- lenge and opportunity, and it’s paying off — the University now ranks in the top 20 for teaching quality nationwide and is the number one university in the East Midlands for graduate employment. Smarter IT through analytics www.nexthink.com “The value of Nexthink lies CHALLENGES in its ability to present data in As part of its mandate to deliver high value learning and growth opportunities, new and meaningful ways, and the University of Derby has invested more than £150 million over the past ten allows us to understand the years in both on-campus and technology infrastructure.