The Films of Andy Warhol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Quinn Captured

Opening ReceptiOn: june 28, 7pm–10pm AdmissiOn is fRee Joan Quinn Captured Curated by Laura Whitcomb and organized by Brand Library Art Galleries panel discussions, talks and film screenings have been scheduled in conjunction with this gallery exhibition. Programs are free and are by reservation only. Tickets may be Joan Quinn Captured reserved at www.glendalearts.org. Join us for the opening reception on Saturday, June 28th, 7:00pm – 10:00pm. 6/28 EmErging LandscapE: 7/17 WarhoL/basquiat/quinn Los angeles 5:00pm film Jean Michel Basquiat: The exhibition ‘Joan Quinn Captured’ will 2:00pm panel Modern Art in Los Angeles: The Radiant Child showcase what is perhaps the largest portrait ‘Cool School’ Oral History Ed Moses 6:30pm panel Warhol & Basquiat: collection by contemporary artists in the world, 3:00PM film LA Suggested by the Art The Magazine of the 80s, Joan including such luminaries as Jean-Michel of Ed Ruscha Quinn’s work for Interview, the Basquiat, Shepard Fairey, Frank Gehry, Manipulator & Stuff Magazine; Robert Graham, David Hockney, Ed Ruscha, 4:30PM panel Los Angeles and the Contemporary Art Dawn Special Speaker Matthew Rolston Beatrice Wood and photographers Robert 7:00pm film Andy Warhol: Mapplethorpe, Helmut Newton, Matthew Rolston and Arthur A Documentary Film Tress. For the first time, this portrait collection will be exhibited in 7/3 EtErnaL rEturn collaboration with renowned works of the artists encouraging a 5:00pm film Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada dialogue between the portraits and specific artist movements. The 7/24 don bachardy exhibition will also portray the world Joan Agajanian Quinn captured 6:30pm film Duggie Fields’ Jangled 6:00pm film Chris & Don: A Love Story as editor for her close friend Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, 7:00pm talk Guest Artist Duggie Fields 7:30pm film Memories of Berlin: along with contributions to some of the most important fanzines of 8:00pm film The Great Wen the 1980’s that are proof of her role as a critical taste maker of her The Twilight of Weimar Culture time. -

The Magic Mushroom Growers Guide Version 3.2 Updated 10-02-96

The Magic Mushroom Growers Guide Version 3.2 Updated 10-02-96 This document provides complete directions for cultivating psilocybin mushrooms in your home. The strain this guide is intended to help you grow is Psilocybe cubensis (Amazonian strain) mushrooms. It is the intent of this document to enable the first time grower to succeed at a minimal cost and with a minimal amount of effort. This growing guide is the only reference you will need. After a person has completed the entire cycle successfully, later generations of mushrooms can be grown with even less cost and effort. The initial cash outlay will be well under $100 for a fully automated shroom factory. Subsequent crops can be produced for several dollars with expected yields of several ounces of dried mushrooms. What has changed since version 3.1 Following is a list of changes made to the document. • Version number was changed from 3.1 to 3.2 • Change pictures in opening. • Suggest ways to get help and provide PGP public key for private messages • Poor Man's terrarium setup. • Bulk growing. • Cris Clays email address and such. • Link to http://www.xs4all.nl/~psee/ as a spore seller. • No more packing of the substrate. • Vacuum cleaner instead of hair dryer. • Link to PF's pages. • Timer stuff. • Arrowhead Mills no longer sells brown rice flour as a mail order item. • Caution about jars sitting flat in boiling pan. • Low humidity cap appearance • Sealing a cake in a jar to reduce contamination risk when growing for spores. • Changing plates after start of spore print for lower contamination risk. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

T"° Anklin News-Record

T"° anklin news-recorD one section, 24 pages / Phone 725-3300 Thursday, January 6, 1977 Second class postage paid at Princeton, N.J. 08540 I!,No. 1 $4.50 a year/t5 cents per copy O0’s chee Washington’s men in Millstone a ViI ge’ Torches light victory 0Portrait"Portrait of a Village"is a carefullyof Somerset Court HouLppreaehed the segched 50-page hislory of Revolutionary Millstone, complete with 100 .maps, most important photographs and other graphic county’." march from battle iisplays. It was published by the Chapter II deal Somerset mrough’s Historic District Com- Court House ant American nissinn to coincide with the reenact- Revolution,and it’ ~ on this chapter nent of the events of January3, 1777. that the ial production The book is edited by Diane Jones "Turnabout" was Hap Heins to Millstone church ;tiney. Othercontributors are Marllyn Sr. contributed a in the way of information and s to this chapter. :antarella, Katharine Erickson, Otherchapters ¢LI with the periods by Peggy Roeske Van Doren, played by Terry 3rnce Marganoff, Patricia Nivlson Special Writer Jamieson, at whose house on River md Barrie Alan Peterson, each of who.n wrote a chapter. times. The final c is "250 Years Road General Washington stayed on of Local ChurchI tracing the It was January 3, 1T/7, all over that night 200 years ago. ’ ~pter I deals with the origins of history of the DuReform Church in again. On Monday evening The play gave the imnression that ~erset Court House tnow Millstone. Washingten’s army marched by torch war was not all *’fun and games."The The chapter concludes: The booksells can be and lantern light into Millstone opening scene was of the British ca- forge, farms, and a variety obtained b following the victory that morningat cups(ion of Millstone (then Somerset all industriesas wellas its legal 359-1361. -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

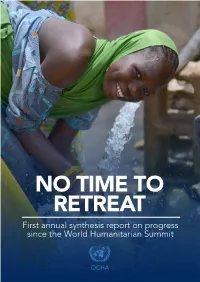

NO TIME to RETREAT First Annual Synthesis Report on Progress Since the World Humanitarian Summit

NO TIME TO RETREAT First annual synthesis report on progress since the World Humanitarian Summit OCHA AGENDA FOR HUMANITY 5 CORE RESPONSIBILITIES 24 TRANSFORMATIONS Acknowledgements: Report drafting team: Kelly David, Breanna Ridsdel, Kathryn Yarlett, Janet Puhalovic, Christopher Gerlach Copy editor: Matthew Easton Design and layout: Karen Kelleher Carneiro Thanks to: Anja Baehncke, Pascal Bongard, Brian Lander, Hugh MacLeman, Alice Obrecht, Rachel Scott, Sudhanshu Singh, Joan Timoney, Hasan Ulusoy, Eugenia Zorbas Cover photo: A girl collects water in Dikwa, Nigeria, where hundreds have fled to escape Boko Haram violence and famine-like conditions. OCHA/Yasmina Guerda © OCHA November 2017 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 02 ABOUT THIS REPORT 17 CORE RESPONSIBILITY ONE: PREVENT AND END CONFLICTS 20 CORE RESPONSIBILITY TWO: RESPECT THE RULES OF WAR 26 2A Protection of civilians and civilian objects 28 2B Ensuring delivery of humanitarian and medical assistance 30 2C Speak out on violations 32 2D Improve compliance and accountability 33 2E Stand up for rules of war 36 CORE RESPONSIBILITY THREE: LEAVE NO ONE BEHIND 38 3A Address displacement 40 3B Address migration 44 3C End Statelessness 46 3D Empower women and girls 47 3E Ensure education for all in crisis 50 3F Enable adolescents and young people to be agents of positive transformation 52 3G Include the most vulnerable 54 CORE RESPONSIBILITY FOUR: WORK DIFFERENTLY TO END NEED 57 4A Reinforce, do not replace, national and local systems 59 4B Anticipate crises 64 4C Transcend the humanitarian-development -

Contemporaries Art Gallery Records

Contemporaries Art Gallery Records LUCILE R. HORSLEY, OWNER-DIRECTOR New Mexico Museum of Art Library and Archives Extent : 3 linear feet Dates : 1962-1967 Language : English Related Materials Many of the artists named in this collection exhibited at this museum. For information about these exhibitions consult the museum's exhibition files and/or catalogs. The museum library also contains separate biographical files for the artists mentioned in this collection. Revised 04/07/2016 Contents Section I - Financial Records Section II - Artists and Visitors Log A. Licenses and Artists' Resumes B. Register of Visitors Section III - Scrapbooks Section IV - Artists and Correspondence Preliminary Comments Artists, Sculptors, and Photographers Section V - Exhibition Flyers Section VI - Gallery Correspondence and Interview A. Correspondence B. The Interview C. Miscellaneous Material Section VII - Photographs - Art and Artists Section VIII- Record Book of Lucile R. Horsley Contemporaries Gallery Page 2 Revised 04/07/2016 Preliminary Statement Lucile R. Horsley (herein LRH), an artist in her own right, organized and opened the Contemporaries Gallery (herein Gallery) in Santa Fe, New Mexico at 418 ½ College Street [now 414 Old Santa Fe Trail] on April 7, 1962. It was one of the first sites for contemporary art showings in the city. She operated it as a "semi-cooperative center" (her words) in which 25 of the finest and most vital painters, sculptors, and photographers of New Mexico could exhibit their work at the same time. By her own admission it was a "pioneering venture." Those who agreed to make monthly payments of LHR's established "fee" schedule were called "Participating Artists." The Gallery remained open for some two and one-half years. -

Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2014 Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation H. King, "Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable," Criticism 56.3 (Fall 2014): 457-479. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/72 For more information, please contact [email protected]. King 6/15/15 Page 1 of 30 Stroboscopic:+Andy+Warhol+and+the+Exploding+Plastic+Inevitable+ by+Homay+King,+Associate+Professor,+Department+of+History+of+Art,+Bryn+Mawr+College+ Published+in+Criticism+56.3+(Fall+2014)+ <insert+fig+1+near+here>+ + Pops+and+Flashes+ At+least+half+a+dozen+distinct+sources+of+illumination+are+discernible+in+Warhol’s+The+ Velvet+Underground+in+Boston+(1967),+a+film+that+documents+a+relatively+late+incarnation+of+ Andy+Warhol’s+Exploding+Plastic+Inevitable,+a+multimedia+extravaganza+and+landmark+of+ the+expanded+cinema+movement+featuring+live+music+by+the+Velvet+Underground+and+an+ elaborate+projected+light+show.+Shot+at+a+performance+at+the+Boston+Tea+Party+in+May+of+ 1967,+with+synch+sound,+the+33\minute+color+film+combines+long+shots+of+the+Velvet+ -

Healthy Eating for Seniors Handbook

Healthy Eating for Seniors Acknowledgements CThehapter Healthy Eating for Seniors1 handbook was originally developed by the British Columbia Ministry of Health in Eat2008. Well, Many seniors Ageand dietitians Well were involved in helping to determine the content for the handbook – providing Therecipes, news isstories good. and Canadian ideas and generallyseniors contributingage 65 to andmaking over are Healthy living Eating longer for thanSeniors ever a useful before. resource. The WellMinistry after they of Health retire, would they like are to continuing acknowledge to and thank all participatethe individuals in their involved communities in the original and development to enjoy of this satisfying,resource. energetic, well-rounded lives with friends and family. For the 2017 update of the handbook, we would like However,to thank recent the public surveys health investigating dietitians from thethe regional eatinghealth and authorities exercise for habits providing of Canadians feedback on – the age nutrition 65 tocontent 84 – revealof the handbook. that seniors The couldupdate bewas doing a collaborative evenproject better. between the BC Centre for Disease Control and the Ministry of Health and made possible through funding from the BC Centre for Disease Control (an agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority). Healthy Eating for Seniors Handbook Update PROJECT TEAM • Annette Anderwald, registered dietitian (RD) • Cynthia Buckett, MBA, RD; provincial manager, Healthy Eating Resource Coordination, BC Centre for Disease Control -

100 Cans by Andy Warhol

Art Masterpiece: 100 Cans by Andy Warhol Oil on canvas 72 x 52 inches (182.9 x 132.1 cm) Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery Keywords: Pop Art, Repetition, Complimentary Colors Activity: 100 Can Collective Class Mural Grade: 5th – 6th Meet the Artist • Born Andrew Warhol in 1928 near Pittsburgh, Pa. to Slovak immigrants. His father died in a construction accident when Andy was 13 years old. • He is known as an American painter, film-maker, publisher and major figure in the pop art movement. • Warhol was a sickly child, his mom would give him a Hershey bar for every coloring book page he finished. He excelled in art and won a scholarship to college. • After college, he moved to New York City and became a magazine illustrator – became known for his drawings of shoes. His mother lived with him – they had no hot water, the bathtub was in the kitchen and had up to 20 cats living with them. Warhol ate tomato soup every day for lunch. Chandler Unified School District Art Masterpiece • In the 1960’s, he started to make paintings of famous American products such as soup cans, coke bottles, dollar signs & celebrity portraits. He became known as the Prince of Pop – he brought art to the masses by making art out of daily life. • Warhol began to use a photographic silk-screen process to produce paintings and prints. The technique appealed to him because of the potential for repeating clean, hard-edged shapes with bright colors. • Andy wanted to remove the difference between fine art and the commercial arts used for magazine illustrations, comic books, record albums or ad campaigns. -

APPEAL US Don't Know! Conference on Artistic Research - 2021-10-02

APPEAL US www.open-frames.net/appeal_us don't know! conference on artistic research - 2021-10-02 15 principles of Black Market International, Michaël La Chance 2 ou 3 chose que je sais d'elle, Jean-Luc Godard 30 minuten, Arjen Ederveen 55 stars, tattooman 56 stars, tattooman 8 1/2, Federico Fellini A Buttle of Coca-Cola, Interview with John Cage A la recherche du temps perdu, Marcel Proust A Voice And Nothing More, Mladen Dolar Accuracy & Aesthetics, Deborah MacPherson Ademkristal, Paul Celan Against Method, Paul Feyerabend Aliens & Anorexia, Chris Kraus All Movies, by Toni Queeckers ALTERMODERN, Nicolas Bourriaud An Anthology of Optimism, Peter de Buysser & Jacob Wren Apparatus for the Distillation of Vague Intuitions, Eve Andree Laramee APPEAL US , all contributors Apur Sansar, Satyajit Ray Arm en Rijk , prof. Davis S. Landes At Land, Maya Deren Bin Jip / 3-Iron (movie), Kim Ki-duk Black Mass, John Gray Body Pressure, Bruce Nauman (1974) Calimero, C in China Call of Cthulhu, HP Lovecraft Canopus in Argos : Archives, Doris Lessing Case Study Homes, Peter Bialobrzeski Catalogue of Strategies, Mieke Gerritzen ea Cheap lecture, Jonathan Burrows Clara et la pénombre , José Carlos Somoza Cornered (1988) , Adrian Piper De man zonder eigenschappen, Robert Musil De Princes Op De Erwt, Hans Christian Andersen Dear Wendy, Thomas Vinterberg / Lars von Trier Decreation, William Forsythe / Anne Carson Deep Democracy of Open Forums, Arnold Mindell Der Mann Ohne Eigenschaften, Robert Musil Der Spiegel im Spiegel, Michael Ende DIAL H–I–S–T–0–R–Y (1997), Johan Grimonprez Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft (2 vols), Niklas Luhmann Disfigured Study, Meg Stuart APPEAL US - http://www.open-frames.net/appeal_us_II/ - Page 1/4 Dodes'kaden ( 1970), Akira Kurosawa Don't Stop Me Now, Queens Don't Stop Me Now , Worldclock Environmental Health Clinic, Natalie Jeremijenko Erotism: Death and Sensuality, Georges Bataille Espèces d'espaces, Georges Perec Flight of the Conchords, HBO series Francis Alys (Contemporary Artists), Francis Alys Franny and Zooey, J.D.