Call of Spirit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Voices, One Nation Booklist A

Many Voices, One Nation Booklist Many Voices, One Nation began as an initiative of past American Library Association President Carol Brey-Casiano. In 2005 ALA Chapters, Ethnic Caucuses, and other ALA groups were asked to contribute annotated book selections that best represent the uniqueness, diversity, and/or heritage of their state, region or group. Selections are featured for children, young adults, and adults. The list is a sampling that showcases the diverse voices that exist in our nation and its literature. A Alabama Library Association Title: Send Me Down a Miracle Author: Han Nolan Publisher: San Diego: Harcourt Brace Date of Publication: 1996 ISBN#: [X] Young Adults Annotation: Adrienne Dabney, a flamboyant New York City artist, returns to Casper, Alabama, the sleepy, God-fearing town of her birth, to conduct an artistic experiment. Her big-city ways and artsy ideas aren't exactly embraced by the locals, but it's her claim of having had a vision of Jesus that splits the community. Deeply affected is fourteen- year-old Charity Pittman, daughter of a local preacher. Reverend Pittman thinks Adrienne is the devil incarnate while Charity thinks she's wonderful. Believer is pitted against nonbeliever and Charity finds herself caught in the middle, questioning her father, her religion, and herself. Alabama Library Association Title: Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café Author: Fannie Flagg Publisher: New York: Random House Date of Publication: 1987 ISBN#: [X] Adults Annotation: This begins as the story of two women in the 1980s, of gray-headed Mrs. Threadgoode telling her life story to Evelyn who is caught in the sad slump of middle age. -

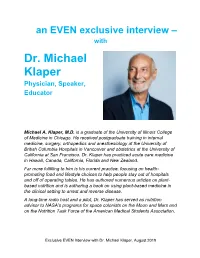

Michael Klaper Physician, Speaker, Educator

an EVEN exclusive interview – with Dr. Michael Klaper Physician, Speaker, Educator Michael A. Klaper, M.D. is a graduate of the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Chicago. He received postgraduate training in internal medicine, surgery, orthopedics and anesthesiology at the University of British Columbia Hospitals in Vancouver and obstetrics at the University of California at San Francisco. Dr. Klaper has practiced acute care medicine in Hawaii, Canada, California, Florida and New Zealand. Far more fulfilling to him is his current practice, focusing on health- promoting food and lifestyle choices to help people stay out of hospitals and off of operating tables. He has authored numerous articles on plant- based nutrition and is authoring a book on using plant-based medicine in the clinical setting to arrest and reverse disease. A long-time radio host and a pilot, Dr. Klaper has served as nutrition advisor to NASA’s programs for space colonists on the Moon and Mars and on the Nutrition Task Force of the American Medical Students Association. Exclusive EVEN Interview with Dr. Michael Klaper, August 2019 He makes the latest information on health and nutrition available through his website, DoctorKlaper.com, where visitors can find the latest nutrition information through his numerous articles and videos, subscribe to his free newsletter, “Medicine Capsule,” and support his “Moving Medicine Forward” Initiative to get applied nutrition taught in medical schools. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ A vegan lifestyle adds a feeling of balance and rightness, and there is also a glimmer of hope attached to veganism that there’ll be a better day tomorrow. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ EVEN recently had an interesting and fun conversation with Dr. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

Brochure1516.Pdf

Da Camera 15-16 Season Brochure.indd 1 3/26/15 4:05 PM AT A SARAH ROTHENBERG SEASONGLANCE artistic & general director SEASON OPENING NIGHT ő Dear Friends of Da Camera, SNAPSHOTS OF AMERICA SARAH ROTHENBERG: Music has the power to inspire, to entertain, to provoke, to fire the imagination. DAWN UPSHAW, SOPRANO; THE MARCEL PROUST PROJECT It can also evoke time and place. With Snapshots: Time and Place, Da Camera GILBERT KALISH, PIANO; WITH NICHOLAS PHAN, TENOR Sō PERCUSSION AND SPECIAL GUESTS Thursday, February 11, 2016, 8:00 PM takes the work of pivotal musical figures as the lens through which to see a Saturday, September 26, 2015; 8:00 PM Friday, February 12, 2016, 8:00 PM decade. Traversing diverse musical styles and over 600 years of human history, Cullen Theater, Wortham Theater Center Cullen Theater, Wortham Theater Center the concerts and multimedia performances of our 2015/16 season offer unique perspectives on our past and our present world. ROMANTIC TITANS: BRENTANO QUARTET: BEETHOVEN SYMPHONY NO. 5 AND LISZT THE QUARTET AS AUTOBIOGRAPHY Our all-star Opening Night, Snapshots of America, captures the essence of the YURY MARTYNOV, PIANO Tuesday, February 23, 2016, 7:30 PM American spirit and features world-renowned soprano Dawn Upshaw. Paris, city Tuesday, October 13, 2015, 7:30 PM The Menil Collection of light, returns to the Da Camera stage in a new multi-media production The Menil Collection GUILLERMO KLEIN Y LOS GUACHOS inspired by the writings of Marcel Proust. ARTURO O'FARRILL Saturday, March 19, 2016, 8:00 PM Two fascinating -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Blaze Damages Ceramic Building

• ev1e Voi.106No.59 University of Delaware, Newqrk. DE Financial aid expecte to be awarded in July By BARBARA ROWLAND To deal with the budgetary The Office of Financial Aid impasse, the university's is anticipating a "bottleneck" financial aid office will send in processing Guaranteed out estimated and unofficial Student Loans (GSLs) as soon award notices on the basis as the federal budget is pass- that the prog19ms will re- ed by-Congr.ess. main the same'-- Because Lhe==amount-oL __- M_ac!)_o_!!ald does 11:0t expect federal funding for both Pell to receive an indication on the Grants and the GSL program amount of. f~ding for Pell has not yet been determined Grants untll this July. the university has not bee~ In an effort to alleviate the - able to award financial aid pressure students may feel packages, according to Direc- -about tuition payments, Mac tor of Financial Aid Douglas Donald said the university MacDonald. will allow students to pay their tuition a quarter at a MacDonald emphasized the time, instead of a half and problem of funding student half installment plan. assistance is not as serious as The university has the problem with delivering also established a $50,000 aid in time for the fall scholarship progr.ani to semester. award students on the basis of MacDonald believes it is both merit and need. unlikely Congress will imple Some of tne changes the ment any changes in the two financial aid office has pro , . _ . Review Photo by Leigh Clifton programs in 1982-83 because jected for next year include: FIREMEN' RESPOND TO A BLAZE at the university's cer'amic building Wednesday night which of the late date. -

Literary, Subsidiary, and Foreign Rights Agents

Literary, Subsidiary, and Foreign Rights Agents A Mini-Guide by John Kremer Copyright © 2011 by John Kremer All rights reserved. Open Horizons P. O. Box 2887 Taos NM 87571 575-751-3398 Fax: 575-751-3100 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.bookmarket.com Introduction Below are the names and contact information for more than 1,450+ literary agents who sell rights for books. For additional lists, see the end of this report. The agents highlighted with a bigger indent are known to work with self-publishers or publishers in helping them to sell subsidiary, film, foreign, and reprint rights for books. All 325+ foreign literary agents (highlighted in bold green) listed here are known to work with one or more independent publishers or authors in selling foreign rights. Some of the major literary agencies are highlighted in bold red. To locate the 260 agents that deal with first-time novelists, look for the agents highlighted with bigger type. You can also locate them by searching for: “first novel” by using the search function in your web browser or word processing program. Unknown author Jennifer Weiner was turned down by 23 agents before finding one who thought a novel about a plus-size heroine would sell. Her book, Good in Bed, became a bestseller. The lesson? Don't take 23 agents word for it. Find the 24th that believes in you and your book. When querying agents, be selective. Don't send to everyone. Send to those that really look like they might be interested in what you have to offer. -

The Ithacan, 1979-11-01

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1979-80 The thI acan: 1970/71 to 1979/80 11-1-1979 The thI acan, 1979-11-01 The thI acan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1979-80 Recommended Citation The thI acan, "The thI acan, 1979-11-01" (1979). The Ithacan, 1979-80. 10. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1979-80/10 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1970/71 to 1979/80 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1979-80 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. f,! ,'I'' A. Weekly Newspaper, Published Independently by the Students of Ithaca College Vol: 49/No. 10 November I. 1979 McCord to Leave Post at IC by Andrea Berm.an cited" about the opportunity, University. said that as of yet, no plans should have been. Charles McCord will be said McCord. But the McCord speculated that the have been set in regards to "In the five years he led our leaving his position as Ithaca "prospect of leaving Ithaca," search for his successor will be filling his position for next development efforts, we have College's V .P. of - College he continued, "where you've starting shortly; hopefully, a semester. raised over $7 million. Our Relations and Resource been for 20 years ... that's a. definite replacement will be in Regarding any projects alumni program has taken on Development to assume the tough one." stated by July. That in presently under his super new vigor, annual giving to the post of Director of University McCord has been with dividual, like McCord, will be vision, McCord said, "there College has more than Relations at the University of Ithaca . -

Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2005 Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Daniels, B. (2005). Daniels, B. (2005). Nondualism and the divine domain. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24(1), 1–15.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 24 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2005.24.1.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nondualism and the Divine Domain Burton Daniels This paper claims that the ultimate issue confronting transpersonal theory is that of nondual- ism. The revelation of this spiritual reality has a long history in the spiritual traditions, which has been perhaps most prolifically advocated by Ken Wilber (1995, 2000a), and fully explicat- ed by David Loy (1998). Nonetheless, these scholarly accounts of nondual reality, and the spir- itual traditions upon which they are based, either do not include or else misrepresent the reve- lation of a contemporary spiritual master crucial to the understanding of nondualism. Avatar Adi Da not only offers a greater differentiation of nondual reality than can be found in contem- porary scholarly texts, but also a dimension of nondualism not found in any previous spiritual revelation. -

The Daily Egyptian, October 06, 1982

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC October 1982 Daily Egyptian 1982 10-6-1982 The aiD ly Egyptian, October 06, 1982 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_October1982 Volume 68, Issue 33 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, October 06, 1982." (Oct 1982). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1982 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in October 1982 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Daily 'Egyptian Wednesday. October II, 19112·VoI. III, No. 33 &aft P .... by Greg Drndma ."'_er Sea. Adlai SleveasOil (left) aIId G~ Jamea TIIomplOll e.c.... ge p9iats III the gubel' DatGr1al debaw at McLeod Tbeater Taesday lliglll. Candidates trade harsh words Voters, was held in. McLeod ~la#i;'~ TMater. It was the third of a series of rour and was the 0IIIy WGN· Trs debate audio cut off ,,'. Both candidates for lllinois one in which the candidates directly asked each other The debate that was to go WGN was using leeds from AI Pizzato, WSIU station governor said they believe statewide education is essential to q\'eStiOIlS. didn't. WSlU, 0uumeI 8, to provide DIP..:Jag.'lI' • alleviate unemployment Stevenson, who proposed to WGN-TV in Chicago lost live coverage over its cable WSW and GTE bad nothing problems and to ensure a stable upgrade teacher training, said Jive audio coverage of the system. However, at about to do with it, be said. The future ior t.'!#! state. -

Hello Goodmorning Remix Ti Lyrics

Hello goodmorning remix ti lyrics Featuring Rick Ross & Nicki Minaj. Hello Good, morning tell me what the lip read; Got that shimmy shimmy ya shimmy yay ayou! Lyrics to Hello Good Morning (Ross & T.I Remix) by Diddy-Dirty Money. Lyrics: [Rick Ross:]/Hello good morning tell me what the lip read;/Pretty face, th. Hello Good morning tell me what the lip read. Diddy - Dirty Money lyrics are property and copyright of their owners. "Hello Good Morning (Remix)" lyrics provided for educational purposes and personal use only. [Rick Ross:] Hello Good morning tell me what the lip read pretty face, thin waist with the sick weave first time. Hello good morning Dirty money Any requests of songs/lyrics rate comment subscribe. Dirty money Hello. T.I ft Dirty Money - Hello, good Morning Lyrics *Dirty* BEST QUALITY! . This and the remix with Eminem are. Nicki Minaj - Envy Lyrics Video - Duration: RoseMathers16 1,, views · Diddy - Dirty Money. Lyrics to 'Hello Good Morning Remix' by Diddy-Dirty Money. Hello Good, morning tell me what the lip read; / Pretty face, thin waist with the sick weave / First. Lyrics of HELLO GOOD MORNING by Puff Daddy feat. Dirty Money and T.I.: Diddy, Hello Good morning, lets go lets ride, Hello Good morning. Lyrics of HELLO GOOD MORNING by Nicki Minaj: Rick Ross Hello Good morning tell me what the lip read, pretty face thin waist with the sick. Dirt Money and Nicki Minaj - Hello Good Morning (Remix) 3. Play | Download. Dirty money Hello good morning Ft rick ross Ti 3. Listen to 'Hello Good Morning (Remix)' by Diddy-Dirty Money Feat.