The Wall a Creative Project Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

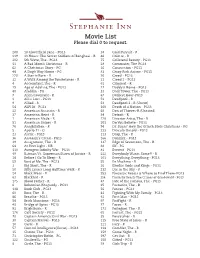

Movie List Please Dial 0 to Request

Movie List Please dial 0 to request. 200 10 Cloverfield Lane - PG13 38 Cold Pursuit - R 219 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi - R 46 Colette - R 202 5th Wave, The - PG13 75 Collateral Beauty - PG13 11 A Bad Mom’s Christmas - R 28 Commuter, The-PG13 62 A Christmas Story - PG 16 Concussion - PG13 48 A Dog’s Way Home - PG 83 Crazy Rich Asians - PG13 220 A Star is Born - R 20 Creed - PG13 32 A Walk Among the Tombstones - R 21 Creed 2 - PG13 4 Accountant, The - R 61 Criminal - R 19 Age of Adaline, The - PG13 17 Daddy’s Home - PG13 40 Aladdin - PG 33 Dark Tower, The - PG13 7 Alien:Covenant - R 67 Darkest Hour-PG13 2 All is Lost - PG13 52 Deadpool - R 9 Allied - R 53 Deadpool 2 - R (Uncut) 54 ALPHA - PG13 160 Death of a Nation - PG13 22 American Assassin - R 68 Den of Thieves-R (Unrated) 37 American Heist - R 34 Detroit - R 1 American Made - R 128 Disaster Artist, The - R 51 American Sniper - R 201 Do You Believe - PG13 76 Annihilation - R 94 Dr. Suess’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas - PG 5 Apollo 11 - G 233 Dracula Untold - PG13 23 Arctic - PG13 113 Drop, The - R 36 Assassin’s Creed - PG13 166 Dunkirk - PG13 39 Assignment, The - R 137 Edge of Seventeen, The - R 64 At First Light - NR 88 Elf - PG 110 Avengers:Infinity War - PG13 81 Everest - PG13 49 Batman Vs. Superman:Dawn of Justice - R 222 Everybody Wants Some!! - R 18 Before I Go To Sleep - R 101 Everything, Everything - PG13 59 Best of Me, The - PG13 55 Ex Machina - R 3 Big Short, The - R 26 Exodus Gods and Kings - PG13 50 Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk - R 232 Eye In the Sky - -

Quentin Tarantino's KILL BILL: VOL

Presents QUENTIN TARANTINO’S DEATH PROOF Only at the Grindhouse Final Production Notes as of 5/15/07 International Press Contacts: PREMIER PR (CANNES FILM FESTIVAL) THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY Matthew Sanders / Emma Robinson Jill DiRaffaele Villa Ste Hélène 5700 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 600 45, Bd d’Alsace Los Angeles, CA 90036 06400 Cannes Tel: 323 207 3092 Tel: +33 493 99 03 02 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From the longtime collaborators (FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, FOUR ROOMS, SIN CITY), two of the most renowned filmmakers this summer present two original, complete grindhouse films packed to the gills with guns and guts. Quentin Tarantino’s DEATH PROOF is a white knuckle ride behind the wheel of a psycho serial killer’s roving, revving, racing death machine. Robert Rodriguez’s PLANET TERROR is a heart-pounding trip to a town ravaged by a mysterious plague. Inspired by the unique distribution of independent horror classics of the sixties and seventies, these are two shockingly bold features replete with missing reels and plenty of exploitative mayhem. The impetus for grindhouse films began in the US during a time before the multiplex and state-of- the-art home theaters ruled the movie-going experience. The origins of the term “Grindhouse” are fuzzy: some cite the types of films shown (as in “Bump-and-Grind”) in run down former movie palaces; others point to a method of presentation -- movies were “grinded out” in ancient projectors one after another. Frequently, the movies were grouped by exploitation subgenre. Splatter, slasher, sexploitation, blaxploitation, cannibal and mondo movies would be grouped together and shown with graphic trailers. -

Arved Birnbaum Birnbaum/

Arved Birnbaum https://www.agentur-birnbaum.de/kuenstler/arved- birnbaum/ Agentur Birnbaum Sabine Birnbaum Phone: +49 177 6332 504 Email: [email protected] Website: www.agentur-birnbaum.de © Peter Bösenberg Information Year of birth 1962 (59 years) Nationality German Height (cm) 176 Languages German: native-language Eye color blue English: medium Hair color Blond Russian: basic Hair length Medium Dialects Ruhr area: only when required Stature full figured Rheinisch: only when required Place of residence Hürth Saxon Housing options Köln, Berlin Lausitzian (lausitzisch): only when required Berlin German Bühnendeutsch: only when required Dance Standard: medium Profession Actor Singing Ballad: medium Chanson: medium Pitch Baritone Primary professional training 1992 Hochschule für Schauspielkunst Ernst Busch Awards 2018 Kroymann Adolf-Grimme-Preis 2016 Weinberg Adolf-Grimme-Preis 2014 Mord In Eberswalde Adolf-Grimme-Preis 2011 Im Angesicht des Verbrechens Adolf-Grimme-Preis 2010 Im Angesicht des Verbrechens Deutscher Fernsehpreis 2008 Eine Stadt wird erpresst Adolf-Grimme-Preis Vita Arved Birnbaum by www.castupload.com — As of: 2021-06-07 Page 1 of 8 Film Die Lügen der Sieger Director: Christoph Hochhäusler 2013 Dessau Dancers Director: Jan Martin Scharf 2010 Hotel Lux Director: Leander Haussmann 2010 BloodRayne 3 Director: Dr.Uwe Boll 2010 Auschwitz Director: Dr. Uwe Boll 2010 Blubberella Director: Dr. Uwe Boll 2009 Wir sind die Nacht Director: Dennis Gansel 2009 Max Schmeling Director: Dr. Uwe Boll 2008 Parkour Director: Marc -

Steffen Mennekes

Steffen Mennekes http://www.mennekes2society.com Agentur aziel Nete Mann Phone: +49 176 2311 7421 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.agentur-aziel.de © Steffi Henn Information Height (cm) 189 Nationality German Weight (in kg) 90 Languages German: native-language Eye color blue English: native-language Hair color Brown French: medium Hair length Bald head Dialects Ruhr area Stature athletic / training Norden Place of residence Berlin Berlin German Cities I could work in München, Köln, Sauerländisch Hamburg, Alicante, English London, Los Angeles, American Mexico-City, New York Sport Baseball, Basketball, Billiards, City, Paris, Sylt, Bodyboarding, Boxing, Soccer, Toronto, Vancouver Rifle shooting, Juggle, Kickboxing, Paintball, Pistol shooting, Rafting, Horse riding, Rowing, Swim, Skateboard, Alpine skiing, Snowboard, Tennis, Table tennis, Volleyball, Wakeboard, Water-skiing, Surfing, Windsurfing, Yoga Dance Salsa: medium Profession Speaker, Actor, Dubbing actor Singing Chanson: professional Rock/Pop: professional Bat: professional A cappella: professional Pitch Baritone Other licenses Sailing surfing licence Other Education & Training 2005 –… versch. Workshops 2016 Hollywood in Rome Acting-Seminar mit Paul Haggis 2004 –… Vancouver Film School, Canada 2001 –… International Network of Actors e.V. Vita Steffen Mennekes by www.castupload.com — As of: 2021-07- 05 Page 1 of 4 Film 2021 The Magic Flute Role: Priest Director: Florian Sigl Producer: Christopher Zwickler, Fabian Wolfart Distribution: Tobis Film GmbH 2018 Wölfe Role: -

Gousa TV and LA REYNA Debut New Latinx Travel Series

NEWS RELEASE GoUSA TV and LA REYNA Debut New Latinx Travel Series WASHINGTON, DC - May 13, 2020 "Americanos” showcases Latinx culture in the United States via a five-part original series premiering May 14, 2020 Brand USA's entertainment network, GoUSA TV, launches its ground-breaking new show, “Americanos,” developed and produced by LA REYNA. LA REYNA is the full-service creative agency born out of a collaboration with Vice’s Virtue and award-winning director Robert Rodriguez’s (“Sin City,” “From Dusk till Dawn,” and “El Mariachi”) El Rey Network. The five-part series chronicles the rich and varied history and experiences of diverse Latinx communities across Austin, Texas; Los Angeles, California; Queens, New York; Tucson, Arizona; and Santa Fe, New Mexico. “Americanos,” introduces viewers to the cities, neighborhoods, and people behind the vibrant Latinx subcultures that make these towns one of a kind places to explore. The series showcases the intricacies of these destinations through the storytelling of influential Latinx personalities such as artists, chefs, musicians, athletes, and creators. “'Americanos' marks a fresh take on destination travel content by celebrating the Latinx communities that define the culture of their cities. We want to give our viewers and potential travelers cultural insight from the many voices of people in America and bring new and exciting cinematic content to the travel marketplace,” said Christopher L. Thompson, president and chief executive officer of Brand USA. The series is authentically brought to life by a Latinx crew and creatives which include Emmy-nominated producer and Cannes Lion-winning director, Daniel Ramirez, and Mariana Blanco. -

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 98: Robert Rodriguez Show Notes and Links at Tim.Blog/Podcast

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 98: Robert Rodriguez Show notes and links at tim.blog/podcast Tim Ferriss: Hello, ladies and germs, puppies and kittens. Meow. This is Tim Ferriss and welcome to another episode of the Tim Ferriss Show, where it is my job to deconstruct world class performers, to teas out the routines, the habits, the books, the influences, everything that you can use, that you can replicated from their best practices. And this episode is a real treat. If you loved the Arnold Schwarzenegger or Jon Favreau or Matt Mullenweg episodes, for instance, you are going to love this one. We have a film director, screen writer, producer, cinematographer, editor, and musician. His name is Robert Rodriguez. His story is so good. While he was a student at University of Texas at Austin, he wrote the script to his first feature film when he was sequestered in a drug research facility as a paid subject in a clinical experiment. So he sold his body for science so that he could make art. And that paycheck covered the cost of shooting his film. Now, what film was that? The film was Element Mariachi, which went on to win the coveted Audience Award at Sundance Film Festival and became the lowest budget movie ever released by a major studio. He went on then, of course, to write and produce a lot, and direct and edit and so on, a lot of films. He’s really a jack of all trades, master of many because he’s had to operate with such low budgets and be so resourceful. -

2016 FEATURE FILM STUDY Photo: Diego Grandi / Shutterstock.Com TABLE of CONTENTS

2016 FEATURE FILM STUDY Photo: Diego Grandi / Shutterstock.com TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THIS REPORT 2 FILMING LOCATIONS 3 GEORGIA IN FOCUS 5 CALIFORNIA IN FOCUS 5 FILM PRODUCTION: ECONOMIC IMPACTS 8 6255 W. Sunset Blvd. FILM PRODUCTION: BUDGETS AND SPENDING 10 12th Floor FILM PRODUCTION: JOBS 12 Hollywood, CA 90028 FILM PRODUCTION: VISUAL EFFECTS 14 FILM PRODUCTION: MUSIC SCORING 15 filmla.com FILM INCENTIVE PROGRAMS 16 CONCLUSION 18 @FilmLA STUDY METHODOLOGY 19 FilmLA SOURCES 20 FilmLAinc MOVIES OF 2016: APPENDIX A (TABLE) 21 MOVIES OF 2016: APPENDIX B (MAP) 24 CREDITS: QUESTIONS? CONTACT US! Research Analyst: Adrian McDonald Adrian McDonald Research Analyst (213) 977-8636 Graphic Design: [email protected] Shane Hirschman Photography: Shutterstock Lionsgate© Disney / Marvel© EPK.TV Cover Photograph: Dale Robinette ABOUT THIS REPORT For the last four years, FilmL.A. Research has tracked the movies released theatrically in the U.S. to determine where they were filmed, why they filmed in the locations they did and how much was spent to produce them. We do this to help businesspeople and policymakers, particularly those with investments in California, better understand the state’s place in the competitive business environment that is feature film production. For reasons described later in this report’s methodology section, FilmL.A. adopted a different film project sampling method for 2016. This year, our sample is based on the top 100 feature films at the domestic box office released theatrically within the U.S. during the 2016 calendar -

Larger Than Life: Communicating the Scale of Prehistoric CG Animals

Larger than Life: Communicating the Scale of Prehistoric CG Animals Valentina Feldman Digital Media Antoinette Westphal College of Media Arts and Design Drexel University Philadelphia, PA 19104 [email protected] Abstract — Since the earliest days of cinema, toying with the This statement can hardly be applied to filmmakers, who perception of scale has given filmmakers the ability to create have historically paid great attention to differences of size. spectacular creatures that could never exist in the physical world. The perception of scale is one of the most widely manipulated With the flexibility of CG visual effects, this trend has persisted in aspects of “movie magic,” and has been so since the earliest the modern day, and blockbuster movies featuring enormous monsters are just as popular as ever. The trend of scaling days of cinema. Films featuring impossibly gigantic creatures creatures to impossible proportions for dramatic effect becomes have dominated the box office since the record-breaking problematic when filmmakers use this technique on non-fictional release of King Kong (1933) [LaBarbera, 2003]. Perhaps creatures. Prehistoric animals in particular have very few unsurprisingly, the trend of giant monsters has only continued scientifically accurate appearances in popular culture, which with the advancement of visual effects technology. Movie means that films such as Jurassic Park play an enormous role in monsters are growing bigger and bigger, and moviemakers determining the public’s view of these animals. When filmmakers arbitrarily adjust the scale of dinosaurs to make them appear show no signs of stopping their ceaseless pursuit of cinematic more fearsome, it can be detrimental to the widespread gigantism. -

Horror Movie Bracket

Horror Movie Bracket First Round Second Round Regionals Semi-Finals Championship Semi-Finals Regionals Second Round First Round PSYCHO SHAUN OF THE DEAD PSYCHO SHAUN OF THE DEAD SUSPIRIA A HAUNTED HOUSE SHAUN OF THE PSYCHO DEAD MISERY THE BURBS STEPHEN KING'S IT THE BURBS STEPHEN KING'S IT SLITHER SHAUN OF JAWS THE DEAD ROSEMARY'S BABY THE LOST BOYS ROSEMARY'S BABY THE LOST BOYS PARANORMAL ACTIVITY JOHN DIES AT THE END BIG TROUBLE IN JAWS LITTLE CHINA JAWS BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE JAWS CHINA SALEM'S LOT HATCHET TEXAS CHAINSAW HORROR MASSACRE GREMLINS COMEDY-HORROR ALIEN ARMY OF DARKNESS I KNOW WHAT YOU DID ALIEN LAST SUMMER I KNOW WHAT YOU DID LAST THE GATE SUMMER BUFFY THE VAMPIRE POLTERGEIST SLAYER NOSFERATU BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER BUFFY THE VAMPIRE POLTERGEIST SLAYER POLTERGEIST YOU'RE NEXT TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE GREMLINS FREAKS GREMLINS TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE GREMLINS THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE CRITTERS TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE GREMLINS THE THING TUCKER AND DALE VS. EVIL DRACULA: DEAD AND THE THING LOVING IT CANDYMAN DRACULA: DEAD AND LOVING IT THE EXORCIST CABIN IN THE WOODS THE EXORCIST CHAMPION CABIN IN THE WOODS THE RING LEPRECHAUN CABIN IN THE THE EXORCIST WOODS NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET MONSTER SQUAD NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET MONSTER SQUAD FRIDAY THE 13TH FROM DUSK TILL DAWN SILENCE CABIN IN OF THE THE LAMBS WOODS NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD RETURN OF THE LIVING DEAD NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD THE FACULTY CHILD'S PLAY THE FACULTY SILENCE OF THE LAMBS IDLE HANDS SILENCE OF THE LAMBS TREMORS SILENCE OF THE LAMBS -

The Films of Uwe Boll Vol. 1

THE FILMS OF UWE BOLL VOL. 1 THE VIDEO GAME MOVIES (2003-2014) MAT BRADLEY-TSCHIRGI MOON BOOKS PUBLISHING CONTENTS Foreword Introduction 1. House of the Dead 2. Alone in the Dark 3. BloodRayne 4. BloodRayne 2: Deliverance 5. In the Name of the King: A Dungeon Siege Tale 6. Postal 7. Far Cry 8. BloodRayne: The Third Reich 9. In the Name of the King 2: Two Worlds 10. Blubberella 11. In the Name of the King 3: The Last Mission Acknowledgments About the Author INTRODUCTION Video games have come a long way, baby. What started as an interactive abstract take on ping pong has morphed into a multi-billion dollar a year industry. When certain video game franchises started making oodles and oodles of money, Hollywood came a knockin' to adapt these beloved properties for the silver screen. Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat, and Resident Evil notwithstanding, audiences didn't flock to the cinema to watch their interactive favorites writ large. However, they sell pretty well on DVD and Blu-ray and tend to be made on a meager budget. Thus, video game movies continue to be released. No director has made more live-action video game feature films than Uwe Boll. Holding a PhD in Literature from The University of Siegen, Dr. Boll has shot nearly a dozen of these pictures. It should be noted his full filmography is quite varied and not just limited to video game adaptations; his other movies are often dramas with political elements and shall be covered in two more forthcoming volumes: The Films of Uwe Boll Vol. -

JJ Abrams Talks Visual Effects

FOLLOW (/) NEWS (HTTP://WWW.IBTIMES.COM.AU/NEWS) J.J. Abrams Talks Visual Effects And 'Challenging’ Work On 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens' By Tanya Diente (/reporters/tanya-diente) @mystidrift (http://www.twitter.com/mystidrift) on February 09 2015 2:31 PM Director J.J. Abrams and his wife Katie McGrath pose at the Children's Defense FundCalifornia 24th Annual "Beat the Odds" Awards in Culver City, California December 4, 2014. Reuters/Mario Anzuoni During his acceptance speech at the Visual Effects Society Awards, J.J. Abrams admitted he was thrilled to have worked on “Star Wars: The Force Awakens.” He said it’s been a thrill working on “Star Wars: The Force Awakens.” The director also expressed his gratitude for Lucasfilm for making his lifetime dream of working on the movie a reality. According to Deadline (http://deadline.com/2015/02/jjabramsstarwarsdreamcometruevesawards1201366546/), J.J. Abrams was especially grateful for head of Lucasfilm Kathleen Kennedy for giving him the opportunity to direct the movie. “I want to thank Kathy Kennedy for saying the words, ‘Do you want to direct Star Wars?’ and actually being in a position to let me direct Star Wars,” he said. Abrams revealed that the past couple of years he’s spent working on “Star Wars: The Force Awakens,” “in the world of light sabers and tie fighters,” has reportedly been “absolutely challenging” for him. The movie has suffered numerous leaks in the past, from plot details to leaked concept art. However, this has not stopped the director from keeping mum on production details. -

Promotional Websites in the Film Industry. the Case of the Spanish Cinema Las Páginas Webs Promocionales En La Industria Cinematográfica

Promotional websites in the film industry. The case of the Spanish cinema Las páginas webs promocionales en la industria cinematográfica. El caso del cine español Sergio Jesús Villén Higueras holds a PhD in Audiovisual Communication and Advertising from the University of Malaga, receiving the European mention. He is a member of various research groups in which he analyses the promotional strategies of the cultural industries on websites and social networks; the ecosystem of Chinese social media and, particularly, the impact of Wechat on young Chinese students; and the cultural and technological transformations that the contemporary Chinese film industry has experimented. University of Málaga, Spain [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-6813-3614 Francisco Javier Ruiz del Olmo is a full professor at the University of Malaga. He develops his teaching and research work in the Faculty of Communication Sciences and the Faculty of Fine Arts. He has investigated the communicative models of audio-visual media and the representation of contemporary audio-visual forms, as well as the technical and social uses of them; a second research line is related to communication and new media. Both work lines have in common a significant interest in the qualitative methodologies. University of Málaga, Spain [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-1953-1798 ISSN: 1696-019X / e-ISSN: 2386-3978 Received: 09/06/2018 - Accepted: 18/09/2018 Recibido: 09/06/2018 - Aceptado: 18/09/2018 Abstract: Resumen: The development of web languages and the new communicative El desarrollo de los lenguajes web y las nuevas necesidades comuni- needs of the film industry have fostered the evolution of official cativas de la industria cinematográfica han favorecido la evolución movie websites.