OBSERVATIONS of BROWN DWARFS Gibor Basri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exoplanet.Eu Catalog Page 1 # Name Mass Star Name

exoplanet.eu_catalog # name mass star_name star_distance star_mass OGLE-2016-BLG-1469L b 13.6 OGLE-2016-BLG-1469L 4500.0 0.048 11 Com b 19.4 11 Com 110.6 2.7 11 Oph b 21 11 Oph 145.0 0.0162 11 UMi b 10.5 11 UMi 119.5 1.8 14 And b 5.33 14 And 76.4 2.2 14 Her b 4.64 14 Her 18.1 0.9 16 Cyg B b 1.68 16 Cyg B 21.4 1.01 18 Del b 10.3 18 Del 73.1 2.3 1RXS 1609 b 14 1RXS1609 145.0 0.73 1SWASP J1407 b 20 1SWASP J1407 133.0 0.9 24 Sex b 1.99 24 Sex 74.8 1.54 24 Sex c 0.86 24 Sex 74.8 1.54 2M 0103-55 (AB) b 13 2M 0103-55 (AB) 47.2 0.4 2M 0122-24 b 20 2M 0122-24 36.0 0.4 2M 0219-39 b 13.9 2M 0219-39 39.4 0.11 2M 0441+23 b 7.5 2M 0441+23 140.0 0.02 2M 0746+20 b 30 2M 0746+20 12.2 0.12 2M 1207-39 24 2M 1207-39 52.4 0.025 2M 1207-39 b 4 2M 1207-39 52.4 0.025 2M 1938+46 b 1.9 2M 1938+46 0.6 2M 2140+16 b 20 2M 2140+16 25.0 0.08 2M 2206-20 b 30 2M 2206-20 26.7 0.13 2M 2236+4751 b 12.5 2M 2236+4751 63.0 0.6 2M J2126-81 b 13.3 TYC 9486-927-1 24.8 0.4 2MASS J11193254 AB 3.7 2MASS J11193254 AB 2MASS J1450-7841 A 40 2MASS J1450-7841 A 75.0 0.04 2MASS J1450-7841 B 40 2MASS J1450-7841 B 75.0 0.04 2MASS J2250+2325 b 30 2MASS J2250+2325 41.5 30 Ari B b 9.88 30 Ari B 39.4 1.22 38 Vir b 4.51 38 Vir 1.18 4 Uma b 7.1 4 Uma 78.5 1.234 42 Dra b 3.88 42 Dra 97.3 0.98 47 Uma b 2.53 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 47 Uma c 0.54 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 47 Uma d 1.64 47 Uma 14.0 1.03 51 Eri b 9.1 51 Eri 29.4 1.75 51 Peg b 0.47 51 Peg 14.7 1.11 55 Cnc b 0.84 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc c 0.1784 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc d 3.86 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc e 0.02547 55 Cnc 12.3 0.905 55 Cnc f 0.1479 55 -

A Review on Substellar Objects Below the Deuterium Burning Mass Limit: Planets, Brown Dwarfs Or What?

geosciences Review A Review on Substellar Objects below the Deuterium Burning Mass Limit: Planets, Brown Dwarfs or What? José A. Caballero Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC, Camino Bajo del Castillo s/n, E-28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain; [email protected] Received: 23 August 2018; Accepted: 10 September 2018; Published: 28 September 2018 Abstract: “Free-floating, non-deuterium-burning, substellar objects” are isolated bodies of a few Jupiter masses found in very young open clusters and associations, nearby young moving groups, and in the immediate vicinity of the Sun. They are neither brown dwarfs nor planets. In this paper, their nomenclature, history of discovery, sites of detection, formation mechanisms, and future directions of research are reviewed. Most free-floating, non-deuterium-burning, substellar objects share the same formation mechanism as low-mass stars and brown dwarfs, but there are still a few caveats, such as the value of the opacity mass limit, the minimum mass at which an isolated body can form via turbulent fragmentation from a cloud. The least massive free-floating substellar objects found to date have masses of about 0.004 Msol, but current and future surveys should aim at breaking this record. For that, we may need LSST, Euclid and WFIRST. Keywords: planetary systems; stars: brown dwarfs; stars: low mass; galaxy: solar neighborhood; galaxy: open clusters and associations 1. Introduction I can’t answer why (I’m not a gangstar) But I can tell you how (I’m not a flam star) We were born upside-down (I’m a star’s star) Born the wrong way ’round (I’m not a white star) I’m a blackstar, I’m not a gangstar I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar I’m not a pornstar, I’m not a wandering star I’m a blackstar, I’m a blackstar Blackstar, F (2016), David Bowie The tenth star of George van Biesbroeck’s catalogue of high, common, proper motion companions, vB 10, was from the end of the Second World War to the early 1980s, and had an entry on the least massive star known [1–3]. -

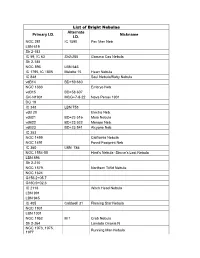

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Search for X-Ray Emission from Bona-Fide and Candidate Brown

A&A manuscript no. (will be inserted by hand later) ASTRONOMY AND Your thesaurus codes are: ASTROPHYSICS 06(08.12.1; 08.12.2; 13.25.5) 11.9.2018 Search for X-ray emission from bona-fide and candidate brown dwarfs R. Neuh¨auser1, C. Brice˜no2, F. Comer´on3, T. Hearty1, E.L. Mart´ın4, J.H.M.M. Schmitt5, B. Stelzer1, R. Supper1, W. Voges1, and H. Zinnecker6 1 MPI f¨ur extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstraße 1, D-85740 Garching, Germany 2 Yale University, Department of Physics, New Haven, CT 06520-8121, USA 3 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 2, D-85748 Garching, Germany 4 Astronomy Department, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 5 Universit¨at Hamburg, Sternwarte, Gojensbergweg 112, D-21029 Hamburg, Germany 6 Astrophysikalisches Institut, An der Sternwarte 16, D-14482 Potsdam, Germany Received 24 Sep 1998; accepted 10 Dec 1998 Abstract. Following the recent classification of the X- for a recent review. They continue to contract until elec- ray detected object V410 x-ray 3 with a young brown tron degeneracy halts further contraction. Depending on dwarf candidate (Brice˜no et al. 1998) and the identifica- metallicity and model assumptions made in for calculating tion of an X-ray source in Chamaeleon as young bona- theoretical evolutionary tracks, the limiting mass between fide brown dwarf (Neuh¨auser & Comer´on 1998), we inves- normal stars and brown dwarfs is ∼ 0.075 to 0.08 M⊙ tigate all ROSAT All-Sky Survey and archived ROSAT (Burrows et al. 1995, 1997, D’Antona & Mazzitelli 1994, PSPC and HRI pointed observations with bona-fide or 1997, Allard et al. -

THE STAR FORMATION NEWSLETTER an Electronic Publication Dedicated to Early Stellar Evolution and Molecular Clouds

THE STAR FORMATION NEWSLETTER An electronic publication dedicated to early stellar evolution and molecular clouds No. 44 — 15 May 1996 Editor: Bo Reipurth ([email protected]) Abstracts of recently accepted papers Lifetimes of Ultracompact HII Regions: High Resolution Methyl Cyanide Observations R.L. Akeson & J.E. Carlstrom Owens Valley Radio Observatory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA We observed the dense molecular cores associated with two ultracompact HII regions, G5.89 + 0.4 and G34.3 + 0.2, in the J=6–5 transitions of CH3CN to probe the temperature and density of the gas. Simultaneously, each region was observed in the J=1–0 transition of a CO isotope to probe the molecular column density. The molecular cores are found to have densities ∼ 106 cm−3 and kinetic temperatures of 90 K and 250 K, respectively. We also find possible evidence for infall of molecular gas toward the HII regions. The lifetime of the HII region ultracompact phase is critically dependent on the properties of the surrounding molecular gas. Based on the number of ultracompact HII regions versus the total number of O stars, it has been suggested that the lifetime of the ultracompact phase is inconsistent with spherical expansion confined only by the ambient medium. We show that for the molecular cloud parameters given above and including the effect of the shell of neutral material formed by the expansion, pressure confinement by the ambient medium may significantly increase the lifetime of the ultracompact phase of the HII regions. Accepted by Ap. J. Probing the initial conditions of star formation: The structure of the prestellar core L1689B P. -

Open Clusters

Open Clusters Open clusters (also known as galactic clusters) are of tremendous importance to the science of astronomy, if not to astrophysics and cosmology generally. Star clusters serve as the "laboratories" of astronomy, with stars now all at nearly the same distance and all created at essentially the same time. Each cluster thus is a running experiment, where we can observe the effects of composition, age, and environment. We are hobbled by seeing only a snapshot in time of each cluster, but taken collectively we can understand their evolution, and that of their included stars. These clusters are also important tracers of the Milky Way and other parent galaxies. They help us to understand their current structure and derive theories of the creation and evolution of galaxies. Just as importantly, starting from just the Hyades and the Pleiades, and then going to more distance clusters, open clusters serve to define the distance scale of the Milky Way, and from there all other galaxies and the entire universe. However, there is far more to the study of star clusters than that. Anyone who has looked at a cluster through a telescope or binoculars has realized that these are objects of immense beauty and symmetry. Whether a cluster like the Pleiades seen with delicate beauty with the unaided eye or in a small telescope or binoculars, or a cluster like NGC 7789 whose thousands of stars are seen with overpowering wonder in a large telescope, open clusters can only bring awe and amazement to the viewer. These sights are available to all. -

Exoplanet.Eu Catalog Page 1 Star Distance Star Name Star Mass

exoplanet.eu_catalog star_distance star_name star_mass Planet name mass 1.3 Proxima Centauri 0.120 Proxima Cen b 0.004 1.3 alpha Cen B 0.934 alf Cen B b 0.004 2.3 WISE 0855-0714 WISE 0855-0714 6.000 2.6 Lalande 21185 0.460 Lalande 21185 b 0.012 3.2 eps Eridani 0.830 eps Eridani b 3.090 3.4 Ross 128 0.168 Ross 128 b 0.004 3.6 GJ 15 A 0.375 GJ 15 A b 0.017 3.6 YZ Cet 0.130 YZ Cet d 0.004 3.6 YZ Cet 0.130 YZ Cet c 0.003 3.6 YZ Cet 0.130 YZ Cet b 0.002 3.6 eps Ind A 0.762 eps Ind A b 2.710 3.7 tau Cet 0.783 tau Cet e 0.012 3.7 tau Cet 0.783 tau Cet f 0.012 3.7 tau Cet 0.783 tau Cet h 0.006 3.7 tau Cet 0.783 tau Cet g 0.006 3.8 GJ 273 0.290 GJ 273 b 0.009 3.8 GJ 273 0.290 GJ 273 c 0.004 3.9 Kapteyn's 0.281 Kapteyn's c 0.022 3.9 Kapteyn's 0.281 Kapteyn's b 0.015 4.3 Wolf 1061 0.250 Wolf 1061 d 0.024 4.3 Wolf 1061 0.250 Wolf 1061 c 0.011 4.3 Wolf 1061 0.250 Wolf 1061 b 0.006 4.5 GJ 687 0.413 GJ 687 b 0.058 4.5 GJ 674 0.350 GJ 674 b 0.040 4.7 GJ 876 0.334 GJ 876 b 1.938 4.7 GJ 876 0.334 GJ 876 c 0.856 4.7 GJ 876 0.334 GJ 876 e 0.045 4.7 GJ 876 0.334 GJ 876 d 0.022 4.9 GJ 832 0.450 GJ 832 b 0.689 4.9 GJ 832 0.450 GJ 832 c 0.016 5.9 GJ 570 ABC 0.802 GJ 570 D 42.500 6.0 SIMP0136+0933 SIMP0136+0933 12.700 6.1 HD 20794 0.813 HD 20794 e 0.015 6.1 HD 20794 0.813 HD 20794 d 0.011 6.1 HD 20794 0.813 HD 20794 b 0.009 6.2 GJ 581 0.310 GJ 581 b 0.050 6.2 GJ 581 0.310 GJ 581 c 0.017 6.2 GJ 581 0.310 GJ 581 e 0.006 6.5 GJ 625 0.300 GJ 625 b 0.010 6.6 HD 219134 HD 219134 h 0.280 6.6 HD 219134 HD 219134 e 0.200 6.6 HD 219134 HD 219134 d 0.067 6.6 HD 219134 HD -

December 2019 BRAS Newsletter

A Monthly Meeting December 11th at 7PM at HRPO (Monthly meetings are on 2nd Mondays, Highland Road Park Observatory). Annual Christmas Potluck, and election of officers. What's In This Issue? President’s Message Secretary's Summary Outreach Report Asteroid and Comet News Light Pollution Committee Report Globe at Night Member’s Corner – The Green Odyssey Messages from the HRPO Friday Night Lecture Series Science Academy Solar Viewing Stem Expansion Transit of Murcury Edge of Night Natural Sky Conference Observing Notes: Perseus – Rescuer Of Andromeda, or the Hero & Mythology Like this newsletter? See PAST ISSUES online back to 2009 Visit us on Facebook – Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Newsletter, Night Visions Page 2 of 25 December 2019 President’s Message I would like to thank everyone for having me as your president for the last two years . I hope you have enjoyed the past two year as much as I did. We had our first Members Only Observing Night (MOON) at HRPO on Sunday, 29 November,. New officers nominated for next year: Scott Cadwallader for President, Coy Wagoner for Vice- President, Thomas Halligan for Secretary, and Trey Anding for Treasurer. Of course, the nominations are still open. If you wish to be an officer or know of a fellow member who would make a good officer contact John Nagle, Merrill Hess, or Craig Brenden. We will hold our annual Baton Rouge “Gastronomical” Society Christmas holiday feast potluck and officer elections on Monday, December 9th at 7PM at HRPO. I look forward to seeing you all there. ALCon 2022 Bid Preparation and Planning Committee: We’ll meet again on December 14 at 3:00.pm at Coffee Call, 3132 College Dr F, Baton Rouge, LA 70808, UPCOMING BRAS MEETINGS: Light Pollution Committee - HRPO, Wednesday December 4th, 6:15 P.M. -

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution

GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy Special Publications No. 1 George Herbig in 1960 —————————————————————– GEORGE HERBIG and Early Stellar Evolution —————————————————————– Bo Reipurth Institute for Astronomy University of Hawaii at Manoa 640 North Aohoku Place Hilo, HI 96720 USA . Dedicated to Hannelore Herbig c 2016 by Bo Reipurth Version 1.0 – April 19, 2016 Cover Image: The HH 24 complex in the Lynds 1630 cloud in Orion was discov- ered by Herbig and Kuhi in 1963. This near-infrared HST image shows several collimated Herbig-Haro jets emanating from an embedded multiple system of T Tauri stars. Courtesy Space Telescope Science Institute. This book can be referenced as follows: Reipurth, B. 2016, http://ifa.hawaii.edu/SP1 i FOREWORD I first learned about George Herbig’s work when I was a teenager. I grew up in Denmark in the 1950s, a time when Europe was healing the wounds after the ravages of the Second World War. Already at the age of 7 I had fallen in love with astronomy, but information was very hard to come by in those days, so I scraped together what I could, mainly relying on the local library. At some point I was introduced to the magazine Sky and Telescope, and soon invested my pocket money in a subscription. Every month I would sit at our dining room table with a dictionary and work my way through the latest issue. In one issue I read about Herbig-Haro objects, and I was completely mesmerized that these objects could be signposts of the formation of stars, and I dreamt about some day being able to contribute to this field of study. -

Cycle 9 Approved Programs

Cycle 9 Approved Programs TYPE OF SCIENCE FIRST NAME LAST NAME INSTITUTION COUNTRY TITLE PROPOSAL CATEGORY A Morphological and Multicolor HST Survey for Ultrafaint Quasars, Sampling A Scott Anderson AR University of Washington United States AGN Broad Redshift Range Antonio Aparicio GO Instituto de Astrofi sica de Canarias Spain GAL Phoenix: "halo/disk" structures in dwarf galaxies John Bahcall GO Institute for Advanced Study United States HS Observing the next nearby supernova Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of Hot Horizontal-Branch Stars in the Globular Cluster Bradford Behr GO California Institute of Technology United States HS M13 David Bennett GO University of Notre Dame United States SP Confirmation of Black Hole, Planetary, and Binary Microlensing Events Klaus P. Beuermann GO Universitaets-Sternwarte Goettingen Germany HS FGS parallaxes of magnetic CVs Luciana Bianchi GO The Johns Hopkins University United States SP The Massive Star Content of NGC 6822 Torsten Boeker SNAP Space Telescope Science Institute United States GAL A Census of Nuclear Star Clusters in Late-Type Spiral Galaxies Ann Boesgaard GO Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii United States CS The Nucleosynthesis of Boron - Benchmarks for the Galactic Disk Howard Bond GO Space Telescope Science Institute United States CS WFPC2 Observations of Astrophysically Important Visual Binaries Howard Bond GO Space Telescope Science Institute United States HS Sakurai's Novalike Object: Real-Time Monitoring of a Stellar Thermal Pulse Amanda Bosh AR Lowell Observatory United States -

![Arxiv:2105.09338V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 16 Jun 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5939/arxiv-2105-09338v2-astro-ph-ga-16-jun-2021-1715939.webp)

Arxiv:2105.09338V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 16 Jun 2021

Draft version June 18, 2021 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 Stars with Photometrically Young Gaia Luminosities Around the Solar System (SPYGLASS) I: Mapping Young Stellar Structures and their Star Formation Histories Ronan Kerr,1 Aaron C. Rizzuto,1, ∗ Adam L. Kraus,1 and Stella S. R. Offner1 1Department of Astronomy, University of Texas at Austin 2515 Speedway, Stop C1400 Austin, Texas, USA 78712-1205 (Accepted May 16, 2021) ABSTRACT Young stellar associations hold a star formation record that can persist for millions of years, revealing the progression of star formation long after the dispersal of the natal cloud. To identify nearby young stellar populations that trace this progression, we have designed a comprehensive framework for the identification of young stars, and use it to identify ∼3×104 candidate young stars within a distance of 333 pc using Gaia DR2. Applying the HDBSCAN clustering algorithm to this sample, we identify 27 top-level groups, nearly half of which have little to no presence in previous literature. Ten of these groups have visible substructure, including notable young associations such as Orion, Perseus, Taurus, and Sco-Cen. We provide a complete subclustering analysis on all groups with substructure, using age estimates to reveal each region's star formation history. The patterns we reveal include an apparent star formation origin for Sco-Cen along a semicircular arc, as well as clear evidence for sequential star formation moving away from that arc with a propagation speed of ∼4 km s−1 (∼4 pc Myr−1). We also identify earlier bursts of star formation in Perseus and Taurus that predate current, kinematically identical active star-forming events, suggesting that the mechanisms that collect gas can spark multiple generations of star formation, punctuated by gas dispersal and cloud regrowth. -

Alma Survey of Circumstellar Disks in the Young Stellar Cluster Ic 348

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–?? (2018) Printed 22 May 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) ALMA SURVEY OF CIRCUMSTELLAR DISKS IN THE YOUNG STELLAR CLUSTER IC 348 D. Ruíz-Rodríguez, 1;2? L. A. Cieza,3;4 J. P. Williams,5 S. M. Andrews,6 D. A. Principe,7 C. Caceres,8;12 H. Canovas,9 S. Casassus,3;10 M. R. Schreiber,3;11;12 and J. H. Kastner1 1Chester F. Carlson Center for Imaging Science, School of Physics & Astronomy, and Laboratory for Multiwavelength Astrophysics, Rochester Institute of Technology, 54 Lomb Memorial Drive, Rochester NY 14623 USA. 2Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2611, Australia 3Millenium Nucleus “Protoplanetary discs in ALMA Early Science", Chile. 4Núcleo de Astronomía, Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad Diego Portales, Av. Ejercito 441, Santiago, Chile. 5Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, 96822, USA. 6Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA, 02138, USA. 7Department of Physics and Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. 8Departamento de Ciencias Fisicas, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Universidad Andres Bello. Av. Fernandez Concha 700, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile. 9European Space Astronomy Centre (ESA), Camino Bajo del Castillo s/n, 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain. 10Universidad de Chile, Camino el Observatorio 1515, Santiago, Chile. 11Instituto de Física y Astronomía, Universidad de Valparaíso, Av. Gran Bretaña 1111, 2360102 Valparaíso, Chile. 12Núcleo Milenio Formación Planetaria - NPF, Universidad de Valparaiso, Av. Gran Bretaña 1111, Valparaiso, Chile. ABSTRACT We present a 1.3 mm continuum survey of the young (2-3 Myr) stellar cluster IC 348, which lies at a distance of 310 pc, and is dominated by low-mass stars (M? ∼ 0.1-0.6 M ).