Growing the Good Growing the Good the Case for Low-Carbon Transition in the Food Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2019 FOOD BUYING CLUB CATALOG Pacnw Region UNFI Will Be Closing Our Auburn Facility in August

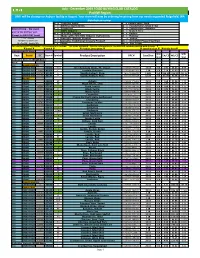

July - December 2019 FOOD BUYING CLUB CATALOG PacNW Region UNFI will be closing our Auburn facility in August. Your store will now be ordering/receiving from our newly expanded Ridgefield, WA distribution center. n = Contains Sugar F = Foodservice, Bulk s = Artificial Ingredients G = Foodservice, Grab n' Go BASICS Pricing = the lowest 4 = Sulphured D = Foodservice, Supplies _ = 100% Organic K = Gluten Free price at the shelf per unit. H = 95%-99% Organic b = Kosher (Except for FIELD DAY items) : = Made with 70%-94% Organic Ingredients d = Holiday * "DC" Column T = Specialty, Natural Product , = Vegan NO CODE= All Warehouses U = Specialty, Traditional Grocery Product m = NonGMO Project Verified W = PacNW - Seattle, WA C = Ethnic w = Fair Trade For placing a SPECIAL ORDER - It is necessary to include: *THE PAGE NUMBER, Plus the information in the BOLDED columns marked with Arrows "▼" * ▼Brand ▼ ▼Item # ▼ ▼ Product Description ▼ ▼ Case/Unit Size ▼ ▼Whlsle Price▼ Indicates BASICS Items WS/ SRP/ Dept Brand DC Item # Symbols Product Description UPC # Case/Size EA/CS WS/CS Brand Unit Unit Indicates Generic BULK Items BULK BULK BAKINGBAKING GOODSGOODS BULK BAKING GOODS 05451 HKnw Dk Chocolate Chips, FT, Vegan 026938-073442 10 LB EA 6.91 69.06 8.99 BULK BAKING GOODSUTWR 40208 F Lecithin Granules 026938-402082 5 LB EA 7.18 35.90 9.35 BULK BAKING GOODSGXUTWR 33140 F Vanilla Extract, Pure 767572-831288 1 GAL EA 336.90 336.90 439.45 BULK BAKING GOODSGUTWR 33141 F Vanilla Extract, Pure 767572-830328 32 OZ EA 95.08 95.08 123.99 BULK BEANSBEANS BULK -

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

Research of Reconstruction of Village in the Urban Fringe Based on Urbanization Quality Improving Üüa Case Study of Xi’Nan Village

SHS Web of Conferences 6, 0200 8 (2014) DOI: 10.1051/shsconf/201460 02008 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2014 Research of Reconstruction of Village in the Urban Fringe Based on Urbanization Quality Improving üüA Case Study of Xi’nan Village Zhang Junjie, Sun Yonglong, Shan Kuangjie School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Guangdong University of Technology, 510090 Guangzhou, China Abstract. In the process of urban-rural integration, it is an acute and urgent challenge for the destiny of farmers and the development of village in the urban fringe in the developed area. Based on the “urbanization quality improving” this new perspective and through the analysis of experience and practice of Village renovation of Xi’nan Village of Zengcheng county, this article summarizes the meaning of urbanization quality in developed areas and finds the villages in the urban fringe’s reconstruction strategy. The study shows that as to the distinction of the urbanization of the old and the new areas, the special feature of the re-construction of the villages on the edge of the cities, the government needs to make far-sighted lay-out design and carry out strictly with a high standard in mind. The government must set up social security system, push forward the welfare of the residents, construct a new model of urban-rural relations, attaches great importance to sustainable development, promote the quality of the villagers, maintain regional cultural characters, and form a strong management team. All in all, in the designing and building the regions, great importance must be attached to verified ways and new creative cooperative development mechanism with a powerful leadership and sustainable village construction. -

An Inquiry Into Animal Rights Vegan Activists' Perception and Practice of Persuasion

An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion by Angela Gunther B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication ! Angela Gunther 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Angela Gunther Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: An Inquiry into Animal Rights Vegan Activists’ Perception and Practice of Persuasion Examining Committee: Chair: Kathi Cross Gary McCarron Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Robert Anderson Supervisor Professor Michael Kenny External Examiner Professor, Anthropology SFU Date Defended/Approved: June 28, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This thesis interrogates the persuasive practices of Animal Rights Vegan Activists (ARVAs) in order to determine why and how ARVAs fail to convince people to become and stay veg*n, and what they might do to succeed. While ARVAs and ARVAism are the focus of this inquiry, the approaches, concepts and theories used are broadly applicable and therefore this investigation is potentially useful for any activist or group of activists wishing to interrogate and improve their persuasive practices. Keywords: Persuasion; Communication for Social Change; Animal Rights; Veg*nism; Activism iv Table of Contents Approval ............................................................................................................................. ii! Partial Copyright Licence ................................................................................................. -

Unilever to Spread Magnum Vegan Reach As Trend Set to Mainstream In

Food and Beverage Innovation December 2018 - 2019 February Volume 17 ISSN 1570-9108 DOUBLE ISSUE Unilever to spread Magnum Vegan reach as trend set to mainstream in 2019 Unilever has introduced its Magnum suitability going forward, with plant-based Vegan ice cream to Australian markets milks and meat substitutes already rapidly with more European markets to follow this moving into the mainstream. year, as the trend towards reformulating The rise of veganism is indicative classic items in vegan forms accelerates. of a growing theme towards mindful At launch, Unilever, described it as a consumption. “velvety plant-based product” that provides Animal welfare and environmental “a creamy experience without the need concerns form clear goals among the for dairy.” “A first for the Australian following of such a strict diet. Vegan market, the 100 percent dairy-free range products are increasingly associated to will feature two of the brand’s signature ethical packaging (50 percent), organic flavors…allowing vegans the opportunity (31 percent), gluten-free (34 percent) and to enjoy and share a moment of pure GMO-free (27 percent) (CAGR 2014-2018). pleasure,” the company said. In 2018, 60 percent of all products with Last year, two new vegan versions vegan claims were reported in Europe. of the popular Magnum ice cream bars continued on page 3 were launched in Sweden and Finland. TOP MARKETTop SUBCATEGORIES market subcategories OF FOOD & BEVERAGES of food LAUNCHES & beverages WITH A “VEGAN” launches CLAIM (GLOBAL, 2018) Magnum Vegan Classic and Magnum with a “vegan” claim (Global, 2018) Vegan Almond, which are European Vegetarian Union approved, are made 6 from a pea protein base and covered in smooth dark chocolate. -

NON-DAIRY MILKS 2018 - TREND INSIGHT REPORT It’S on the Way to Becoming a $3.3 Billion Market, and Has Seen 61% Growth in Just a Few Years

NON-DAIRY MILKS 2018 - TREND INSIGHT REPORT It’s on the way to becoming a $3.3 billion market, and has seen 61% growth in just a few years. Non-dairy milks are the clear successor to cow (dairy) milk. Consumers often perceive these products as an answer to their health and wellness goals. But the space isn’t without challenges or considerations. In part one of this two- part series, let’s take a look at the market, from new product introductions to regulatory controversy. COW MILK ON THE DECLINE Cow milk (also called dairy milk) has been on the decline since 2012. Non-dairy milks, however, grew 61% in the same period. Consumers are seeking these plant-based alternatives that they believe help them feel and look better to fulfill health and wellness goals. Perception of the products’ health benefits is growing, as consumers seek relief from intolerance, digestive issues and added sugars. And the market reflects it. Non-dairy milks climbed 10% per year since 2012, a trend that’s expected to continue through 2022 to become a $3.3 billion-dollar market.2 SOY WHAT? MEET THE NON-DAIRY MILKS CONSUMERS CRAVE THREE TREES UNSWEETENED VANILLA ORGANIC ALMONDMILK Made with real Madagascar vanilla ALMOND MILK LEADS THE NON-DAIRY MILK bean, the manufacturer states that the CATEGORY WITH 63.9% MARKET SHARE drink contains more almonds, claims to have healthy fats and is naturally rich and nourishing with kitchen-friendly ingredients. As the dairy milk industry has leveled out, the non-dairy milk market is growing thanks to the consumer who’s gobbling up alternatives like almond milk faster than you can say mooove. -

Moy Park (Bondco)

NOT FOR GENERAL DISTRIBUTION OFFERING MEMORANDUM IN THE UNITED STATES DATED MAY 1, 2015 Moy Park (Bondco) Plc £100,000,000 6.25% Senior Notes due 2021 (Irrevocably and unconditionally guaranteed by Moy Park Holdings (Europe) Limited and certain subsidiaries of Moy Park Holdings (Europe) Limited) _______________________________ Moy Park (Bondco) Plc (the “Issuer”), a public limited company incorporated under the laws of Northern Ireland, is offering £100,000,000 aggregate principal amount of 6.25% senior notes due 2021 (the “Notes”). The Notes are being offered as a further issuance of the Issuer’s 6.25% Senior Notes due 2021, and will be consolidated with, and form a single series with, the £200,000,000 principal amount of the notes that were originally issued on May 29, 2014, which we refer to in this Offering Memorandum as the “Initial Notes.” Interest on the Notes will be payable semi-annually on each May 29 and November 29 beginning on May 29, 2015. The Notes will mature on May 29, 2021. Prior to May 29, 2017, we will be entitled at our option to redeem all or a portion of the Notes by paying a customary “make-whole” premium. At any time on or after May 29, 2017, we may redeem all or a portion of the Notes by paying a specific premium to you as set forth in this Offering Memorandum (the “Offering Memorandum”). On or before May 29, 2017, we may redeem up to 35% of the aggregate principal amount of the Notes with the net proceeds of certain equity offerings. -

Why Consumers Are Shifting to Plant-Based Eating

WHY CONSUMERS ARE SHIFTING TO PLANT-BASED EATING Consumers say they choose to eat more plant-based foods due to a variety RESTAURANT of reasons including improving their overall health, weight management, TOOL KIT a desire to eat “clean,” and to eat more sustainably. These self-reported motivators are most likely reinforced by the media attention that plant-based celebrities and athletes garner as well as the movies that have been released over the past few years calling attention to the health and planetary concerns of a diet that includes meat. HEALTH WEIGHT MANAGEMENT The main reason consumers say they reduce their meat In a 2017 national survey by market research firm consumption is to be healthy and feel well physically. Nielsen, a whopping 62% of U.S. consumers listed It’s well-known that meat consumption is directly linked weight management as one of the benefits of plant- to the rise of obesity and to an increased risk for several based eating.2 For the seventh consecutive year, U.S. types of cancer, stroke, cardiovascular disease, lung News & World Report voted the plant-based eating disease and diabetes. According to the CDC, nearly 1 plan the best choice overall for losing and maintaining in 3 Americans has high cholesterol, which puts them at weight.3 Plant-based diets are typically higher in fiber, risk for several of those diseases.1 Because plant-based help people feel full longer, and they usually contain a foods contain no cholesterol, consumers with health higher percentage of fruits and vegetables which are less concerns are highly motivated to eat more of them. -

MEAT ATLAS Facts and Fi Gures About the Animals We Eat IMPRINT/IMPRESSUM

MEAT ATLAS Facts and fi gures about the animals we eat IMPRINT/IMPRESSUM The MEAT ATLAS is jointly published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, Berlin, Germany, and Friends of the Earth Europe, Brussels, Belgium Executive editors: Christine Chemnitz, Heinrich Böll Foundation Stanka Becheva, Friends of the Earth Europe Managing editor: Dietmar Bartz Art director: Ellen Stockmar English editor: Paul Mundy Copy editor: Elisabeth Schmidt-Landenberger Proofreader: Maria Lanman Research editors: Bernd Cornely, Stefan Mahlke Contributors: Michael Álvarez Kalverkamp, Wolfgang Bayer, Stanka Becheva, Reinhild Benning, Stephan Börnecke, Christine Chemnitz, Karen Hansen-Kuhn, Patrick Holden, Ursula Hudson, Annette Jensen, Evelyn Mathias, Heike Moldenhauer, Carlo Petrini, Tobias Reichert, Marcel Sebastian, Shefali Sharma, Ruth Shave, Ann Waters-Bayer, Kathy Jo Wetter, Sascha Zastiral Editorial responsibility (V. i. S. d. P.): Annette Maennel, Heinrich Böll Foundation This publication is written in International English. First Edition, January 2014 Production manager: Elke Paul, Heinrich Böll Foundation Printed by möller druck, Ahrensfelde, Germany Climate-neutral printing on 100 percent recycled paper. Except for the copyrighted work indicated on pp.64–65, this material is licensed under Creative Commons “Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported“ (CC BY-SA 3.0). For the licence agreement, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode, and a summary (not a substitute) at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en. This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Development Fields project, funded by the European Commission. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Friends of the Earth Europe and the Heinrich Boell Foundation and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Commission. -

Fringe Season 1 Transcripts

PROLOGUE Flight 627 - A Contagious Event (Glatterflug Airlines Flight 627 is enroute from Hamburg, Germany to Boston, Massachusetts) ANNOUNCEMENT: ... ist eingeschaltet. Befestigen sie bitte ihre Sicherheitsgürtel. ANNOUNCEMENT: The Captain has turned on the fasten seat-belts sign. Please make sure your seatbelts are securely fastened. GERMAN WOMAN: Ich möchte sehen wie der Film weitergeht. (I would like to see the film continue) MAN FROM DENVER: I don't speak German. I'm from Denver. GERMAN WOMAN: Dies ist mein erster Flug. (this is my first flight) MAN FROM DENVER: I'm from Denver. ANNOUNCEMENT: Wir durchfliegen jetzt starke Turbulenzen. Nehmen sie bitte ihre Plätze ein. (we are flying through strong turbulence. please return to your seats) INDIAN MAN: Hey, friend. It's just an electrical storm. MORGAN STEIG: I understand. INDIAN MAN: Here. Gum? MORGAN STEIG: No, thank you. FLIGHT ATTENDANT: Mein Herr, sie müssen sich hinsetzen! (sir, you must sit down) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Entschuldigen sie bitte! Gehen sie zu ihrem Sitz zurück! [please, go back to your seat!] FLIGHT ATTENDANT: (on phone) Kapitän! Wir haben eine Notsituation! (Captain, we have a difficult situation!) PILOT: ... gibt eine Not-... (... if necessary...) Sprechen sie mit mir! (talk to me) Was zum Teufel passiert! (what the hell is going on?) Beruhigen ... (...calm down...) Warum antworten sie mir nicht! (why don't you answer me?) Reden sie mit mir! (talk to me) ACT I Turnpike Motel - A Romantic Interlude OLIVIA: Oh my god! JOHN: What? OLIVIA: This bed is loud. JOHN: You think? OLIVIA: We can't keep doing this. -

Impossible Foods

IMPOSSIBLE FOODS MISSION Our mission is to restore biodiversity and reduce the impact of climate change by transforming the global food system. To do this, we make delicious, nutritious, affordable and sustainable meat, fish and dairy from plants. Animal agriculture occupies nearly half of the world’s land, is responsible for 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions and consumes 25% of the world’s freshwater. We make meat using a small fraction of land, water and energy, so people can keep eating what they love. FOUNDING STORY During a sabbatical in 2009, Stanford University Professor Dr. Patrick O. Brown decided to switch the course of his career to address the urgent problem of climate change. In particular, he wanted to make the global food system sustainable by making meat, fish and dairy from plants — which have a much lower carbon footprint than meat, fish and dairy from animals. Pat brought together a team of top scientists to analyze meat at the molecular level and determine precisely why meat smells, handles, cooks and tastes the way it does. Together, we developed a world-class archive of proprietary research and technology to recreate the entire sensory experience of meat, dairy and fish using plants. We debuted our first product, Impossible Burger, in 2016, and we plan to commercialize additional meat, fish and dairy products around the world. BACKGROUND Founded on: July 16, 2011 CEO/FOUNDER Number of Employees: 600 Dr. Patrick (“Pat”) O. Brown, M.D. Ph.D: Professor Emeritus in Headquarters: Redwood City, California, USA Stanford University’s Biochemistry Department at the School Markets: USA, Canada, Hong Kong, Macau and Singapore of Medicine; co-founder of the Public Library of Science (PLOS); inventor of the DNA microarray; member of the OPERATIONS United States National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine; fellow of the American Association Our first large-scale food manufacturing site is located in Oakland, for the Advancement of Science; former investigator at the California. -

Impossible™ Foods and Posthumanism in the Meat Aisle

humanities Article Grilling Meataphors: Impossible™ Foods and Posthumanism in the Meat Aisle Paul Muhlhauser 1,* , Marie Drews 2 and Rachel Reitz 1 1 English Department, McDaniel College, Westminster, MD 21157, USA; [email protected] 2 English Department, Luther College, Decorah, IA 52101, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: There has always been a posthuman aspect to the processing and consumption of animal- based meats, especially as cuts of meat are distanced from the animals supplying them, thus turning the animals themselves into information more so than bodies. Plant-based meat has doubled down on its employment of posthuman rhetoric, to become what the authors suggest are meataphors, or the articulation of meat as a pattern of information mapped onto a substrate in a way that is not exclusively linguistic. Impossible™ Foods’s meats, in particular, can be considered meataphors that participate in a larger symbolic and capitalistic endeavor to stake a claim in the animal-based meat market using more traditional advertising strategies; however, Impossible™ Foods’s meats are also, more implicitly, making posthuman moves in their persuasive efforts, rhetorically shifting both the meaning of meat and what it means to choose between animal-based and plant-based meats, in a way that parallels posthumanism’s emphasis on information. Impossible™ Foods, through their persuasive practices, has generated a new narrative of what sustains bodies, beyond the spatially significant juxtapositions with animal-based meats. Impossible™ Foods takes on the story of meat and remediates it for audiences through their semiotic practices, thus showing how the company employs a posthumanist approach to meat production and consumption.