Newtown Jerpoint Heritage Conservation Plan 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Castlecomer Plateau

23 The Castlecomer plateau By T. P. Lyng, N.T. HE Castlecomer Plateau is the tableland that is the watershed between the rivers Nore and Barrow. Owing T to the erosion of carboniferous deposits by the Nore and Barrow the Castlecomer highland coincides with the Castle comer or Leinster Coalfield. Down through the ages this highland has been variously known as Gower Laighean (Gabhair Laighean), Slieve Margy (Sliabh mBairrche), Slieve Comer (Sliabh Crumair). Most of it was included within the ancient cantred of Odogh (Ui Duach) later called Ui Broanain. The Normans attempted to convert this cantred into a barony called Bargy from the old tribal name Ui Bairrche. It was, however, difficult territory and the Barony of Bargy never became a reality. The English labelled it the Barony of Odogh but this highland territory continued to be march lands. Such lands were officially termed “ Fasach ” at the close of the 15th century and so the greater part of the Castle comer Plateau became known as the Barony of Fassadinan i.e. Fasach Deighnin, which is translated the “ wi lderness of the river Dinan ” but which officially meant “ the march land of the Dinan.” This no-man’s land that surrounds and hedges in the basin of the Dinan has always been a boundary land. To-day it is the boundary land between counties Kil kenny, Carlow and Laois and between the dioceses of Ossory, Kildare and Leighlin. The Plateau is divided in half by the Dinan-Deen river which flows South-West from Wolfhill to Ardaloo. The rim of the Plateau is a chain of hills averag ing 1,000 ft. -

Archaeological Impact Assessment of the Proposed Construction of Housing at Ladyswell, Thomastown, Co

Mary Henry Archaeological Services Ltd. Archaeological Impact Assessment of the Proposed Construction of Housing at Ladyswell, Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny. Archaeological Consultant: Mary Henry Archaeological Services Ltd. Site Type: Urban Planning Ref. No.: N/A Report Author: Mary Henry Report Status: Final Date of Issue: 7th October 2019. _____________________________________________________________________ Archaeological Impact Assessment of a Proposed Housing Development at Ladyswell, Thomastown,. Co. Kilkenny. 1 Mary Henry Archaeological Services Ltd. Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Siting 3 3. Method 6 4. Historical and Archaeological Background of Thomastown 7 5. Historical and Archaeological Background of the PDS 13 6. Site Inspection 16 7. Impact Assessment and Mitigation Measures 21 Appendix One: List of Artefacts Recorded in the National Museum of Ireland Topographical Files and Finds Registers from Thomastown and its Environs List of Figures Figure 1 RMP Sheet No. 28. Study Area Highlighted in Green. Figure 2 Study Area Highlighted in Yellow and Proposed Development Site in Red. Figure 3 First Edition OS Map (1839). 6-Inch Series. Figure 4 Second Edition OS Map, (1900). 25-Inch Series. _____________________________________________________________________ Archaeological Impact Assessment of a Proposed Housing Development at Ladyswell, Thomastown,. Co. Kilkenny. 2 Mary Henry Archaeological Services Ltd. 1. Introduction This report outlines the findings from an archaeological desktop assessment of the proposed construction of social housing within lands owned by Kilkenny County Council at Ladyswell, Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny. It was commissioned by Kilkenny County Council who require an assessment of the site from an archaeological perspective as part of advance preparatory works and to determine the need or extent of a full Archaeological Impact Assessment (AIA) before proceeding with the housing project. -

Thomastown to Inistioge Nore Valley Walk

Thomastown to Inistioge Nore Valley Walk Nore Valley Walk East Cycle Route Mill TASTE of Kilkenny Historic House Food Hub Country House MADE in Kilkenny Craft Hub Garden The Nore Cot Grennan Mill START FINISH Trailhead Directions to Trailhead start/end point Difficulty Moderate From Thomastown: Starting in the town of Grennan Length 10.9km Castle East Kilkenny Thomastown go south across the bridge and follow the CycleCycle Route green arrows to the Thomastown GAA pitch. Walk along Duration 2-3 hours the border of the GAA pitch to the river bank. Additional To protect farm animals, info no dogs allowed From Inistioge: Approaching form the village square, arrive at the riverbank and turn left along the river. Overview This stretch of the Nore Valley Walk takes you through diverse countryside, pastoral lands and woodland; rich in flora and fauna. The river is noted for its salmon and also holds crayfish and otters and the arches of its bridges are favoured roosting spots for Daubenton bats. Steeped in history, since the 12th century the Nore was a vital Ballydu House trading route for export of corn, hides and livestock and the importation of exotic goods from other parts of the world such as wine, tobacco, cloth and spices via New START Ross and Waterford. There is the ruin of Grennan Castle built by Strongbow’s son-in- FINISH law in the 13th century at the start of the walk and through the pretty Dysart Woods, carpeted in springtime with wood anemones, bluebells and primroses. You’ll pass the ruins of Dysart Castle, home to philosopher Bishop George Berkeley who mused ‘are Woodstock Gardens objects there if we do not perceive them’?! The trail leads you on by Ballyduff House; a glorious Georgian country house in its stunning parkland setting, before entering the broadleaf Brownsbarn Wood and along a grassy riverside track where the view of the 10 arch bridge in picturesque Inistioge opens up ahead of you. -

Ireland's Solar Value Chain Opportunity

Ireland’s Solar Value Chain Opportunity Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) with input and analysis from Ricardo Energy & Environment. The study was informed by inputs from stakeholders from research and industry with expertise in solar PV. SEAI is grateful to all stakeholders who took part in the workshop and interviews, with particular thanks to representatives from IDA Ireland, Enterprise Ireland, Science Foundation Ireland, Dublin Institute of Technology, Nines Photovoltaics, BNRG, redT Energy, Electronic Concepts Ltd, the Irish Solar Energy Association, Kingspan ESB, Lightsource, Dublin City University, Waterford IT, University College Dublin, University of Limerick and Trinity College Dublin. A full list of stakeholders consulted can be found in Appendix C. April 2017 Contents Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 11 2. Solar PV Status in Ireland 15 2.1 Current Measures Promoting Solar PV in Ireland 18 3. Mapping the Solar PV ‘Wider Value Chain’ 21 3.1 Value Distribution Assessment 23 3.2 Wider Value Chain Maps 24 4. Strengths & Opportunities 33 4.1 Value Chain Strengths 34 4.2 Value Chain Opportunities 38 5. Value Proposition 41 5.1 Uptake Scenarios 42 5.2 Market Size Scenarios 43 5.3 Irish Market Share 50 6. Priorities and Next Steps 53 7. Conclusion 55 Appendices Appendix A: Value Distribution Maps for different 56 scenarios and applications Appendix B: Source of Market Data 72 Appendix C: Stakeholders Consulted 73 Executive Summary This report examines in detail the global solar photovoltaic (PV) value chain, Ireland’s strengths within it and opportunities for Irish research and industry to capture value and new business from a growing international solar PV market out to 2030. -

Route 817 Kilkenny - Castlecomer - Athy - Kilcullen - Naas - Dublin City

Route 817 Kilkenny - Castlecomer - Athy - Kilcullen - Naas - Dublin City DAILY M-F Kilkenny Ormond House, Ormond Road 10:30 xxxx Castlecomer Church, Kilkenny Street 10:50 13:20 Moneenroe Railyard Junction 10:54 13:24 Crettyard Northbound 10:55 13:25 Newtown Cross Opp Flemings Pub 11:00 13:30 Ballylynan Cross Jct Village Estate 11:05 13:35 Athy C Bar Leinster Street 11:15 13:45 Kilmead CMC Energy 11:21 13:51 Ballyshannon Kildare Eastbound 11:28 13:58 Kilcullen Opp Frasers Garage 11:35 14:05 Kilcullen Lui Nia Greine 11:37 14:07 Carnalway Northbound 11:40 14:10 Two Mile House Northbound 11:43 14:13 Kilashee Opp. Kilashee Hotel 11:45 14:15 Naas Hospital Ballymore Road 11:50 14:20 Naas Post Office 11:55 14:25 Connect to BE Route 126 in Naas Newlands Cross Northbound 12:20 xxxx Dublin Heuston Heuston Station 12:40 xxxx Dublin City Eden Quay 12:50 15:35 Arrival time at O'Connell Bridge DAILY Mondays to Sundays including Bank Holidays M-F Mondays to Fridays excluding Bank Holidays Route 817 Dublin City - Naas - Kilcullen - Athy - Castlecomer - Kilkenny M-F DAILY Dublin City Georges Quay 09:30 BE Route 126 Connolly Luas Stop 16:00 Dublin City Halfpenny Bridge xxxx 16:05 Dublin Heuston Heuston Station xxxx 16:10 Newlands Cross Southbound xxxx 16:30 Naas Opp. Post Office 10:40 Connection from Dublin 16:55 Naas Hospital Ballymore Road 10:45 17:00 Kilashee Kilashee Hotel 10:50 17:05 Two Mile House Southbound 10:52 17:07 Carnalway Southbound 10:55 17:10 Kilcullen Opp. -

The Non·Agricultural Working Class in 19Th Century Thomastown Wide Region

William Murphy (ed.), In the shadow of the steeple II. Kilkenny: Duchas-Tullaherin Parish Heritage society, 1990. The Non·Agricultural Working Class in 19th Century Thomastown wide region. "The boats that now navigate from lni,tioge to by Marilyn Silverman. Thomastown carry 13 or 14 ton down the river when it is full Irish historians, both professionals and amateurs, tend to and can sometimes bring up 10 ton, but only 3 or 4 when th~ see rural parishes as made up of farms, farmers and water is low. They are drawn by eight men and require two agricultural labourers. Similarly, they tend to study the non· more to c~nduct the boat, and are helped occasionally by a agricultural working classes, such as industrial labourers, square saIl; the men are paid 13d. a day, with three penny only in the cities. In this paper, I try to bridge this gap by worth of bread, or 3d. in lieu of it".' describing a non-agricultural, labouring class in Another example is a report in the Kilkenny Moderator of Thomastown parish during the nineteenth century. March 9,1816 on a Grand Jury Presentment Session where it was decided to build "a new line ofroad between Thomastown Finding the Non-agricultural Labourer: 1800-1901 and Mullinavat, by which the ascents ... along ... the Walsh For people in Dublin, Waterford, Kilkenny City or New mountains will be avoided". The jurors stated that the Ross, Thomastown parish is "up the country" and "very project not only would help farmers and Waterford rural". It is made up of 54 townlands containing merchants, but that benefits would "follow to the county approximately 20,450 acres of which 100 or so function as a from the clrculatlon of so much money among the labouring small service centre with shops and relatively dense housing. -

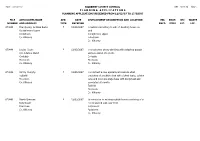

File Number Kilkenny County Council P L a N N I N G a P P L I C a T I O N S Planning Applications Received from 11/03/07 to 17

DATE : 22/03/2007 KILKENNY COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 09:04:46 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 11/03/07 TO 17/03/07 FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER AND ADDRESS TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 07/443 Paul Quealy & Jillian Burke P 12/03/2007 to build conservatory to side of dwelling house on Donaghmore Upper land Johnstown Donaghmore Upper Co. Kilkenny Johnstown Co. Kilkenny 07/444 Louise Doyle P 12/03/2007 to erect a two storey dwelling with detached garage C/o Julianne Walsh and associated site works Corluddy Corluddy Mooncoin Mooncoin Co. Kilkenny Co. Kilkenny 07/445 Jimmy Dunphy P 12/03/2007 to construct a new agricultural livestock shed Tubbrid consisting of a cubicle shed with slatted tanks, calving Mooncoin pens and concrete silage base with dungstead and Co. Kilkenny associated site works Tubbrid Mooncoin Co. Kilkenny 07/446 Martin Brennan P 12/03/2007 for extension to existing cubicle house consisting of a Kellymount roofed slatted tank easi-feed Paulstown Kellymount Co. Kilkenny Paulstown Co. Kilkenny DATE : 22/03/2007 KILKENNY COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 09:04:46 PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 11/03/07 TO 17/03/07 FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER AND ADDRESS TYPE RECEIVED RECD. -

R713/R448 Knocktopher to Ballyhale Footpath

19101-01-002 R713/R448 Knocktopher to Ballyhale Footpath Part 8 of Planning and Development Regulations 2001 (As Amended) Report on the Nature, Extent and Principal Features of the Proposed Development for Kilkenny County Council 7, Ormonde Road Kilkenny Tel: 056 7795800 January 2020 - Rev B TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION & NEED FOR SCHEME .............................................................. 1 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................... 2 3. PLANNING CONTEXT ............................................................................................ 3 4. CONSTRUCTION MITIGATION MEASURES ......................................................... 4 5. PART 8 PUBLIC CONSULTATION ......................................................................... 5 APPENDIX A - DRAWINGS ........................................................................................... 6 Kilkenny Co Co R713/R448 Knocktopher to Ballyhale Footpath Roadplan 1. INTRODUCTION & NEED FOR SCHEME The villages of Knocktopher and Ballyhale in south Kilkenny are linked by the R713 Regional Road. However, there is an absence of a continuous pedestrian linkage between the two villages. Presently there are footpaths extending south from Knocktopher and north from Ballyhale. These footpaths were constructed over a number of phases with the most recent in 2010. There is a gap of approximately 858m between the extremities of both these footpaths. Figure 1.1 - Location Map Completing this section of -

3588 Cultural Heritage Final 20081111

Environmental Impact Statement – Extension to Existing Quarry (OpenCast Mine) Roadstone Provinces Ltd. Dunbell Big Td., Maddockstown, Bennettsbridge, Co. Kilkenny (Section 261 Quarry Ref. QY2) SECTION 3.9 – Cultural Heritage CONTENTS 3.9.1. INTRODUCTION i. Outline of scope of works General The Development ii. Project team iii. Consultations 3.9.2. BASELINE ENVIRONMENTAL STUDY i. Outline of the baseline study ii. Baseline study methodology iii. Field Inspection 3.9.3. RECEIVING ENVIRONMENT, HISTORICAL & ARCHAEOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE i. The Landscape ii. Historical Background 3.9.4. BUILDINGS 3.9.5. ARCHAEOLOGY i. Archaeological Assessment ii. Field Inspection 3.9.6. ASSESSMENT OF POTENTIAL For inspection IMPACTS purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. i. Direct Impacts ii. Indirect Impacts iii. Interaction with Other Impacts iv. ‘Do Nothing Scenario’ v. ‘Worst Case Impact’ 3.9.7. RECOMMENDATIONS i. Direct Impacts ii. Indirect Impacts 3.9.8. BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDICES Appendix 3.9.1 SITES ENTERED IN THE RECORD OF MONUMENTS AND PLACES 3588/EIS/cm November 2008 Section 3.9 – Page 1 EPA Export 20-10-2017:03:35:38 Environmental Impact Statement – Extension to Existing Quarry (OpenCast Mine) Roadstone Provinces Ltd. Dunbell Big Td., Maddockstown, Bennettsbridge, Co. Kilkenny (Section 261 Quarry Ref. QY2) 3.9.1. INTRODUCTION i Outline of Scope of Works General This report, prepared on behalf of Roadstone Provinces, has been undertaken to assess the impacts on the cultural heritage of the development of quarrying on c15.3 hectares of land in the townland of Dunbell Big, Co. Kilkenny (see Fig. 3.9.1). A wide variety of paper, cartographic, photographic and archival sources was consulted. -

The War of Independence in County Kilkenny: Conflict, Politics and People

The War of Independence in County Kilkenny: Conflict, Politics and People Eoin Swithin Walsh B.A. University College Dublin College of Arts and Celtic Studies This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the Master of Arts in History July 2015 Head of School: Dr Tadhg Ó hAnnracháin Supervisor of Research: Professor Diarmaid Ferriter P a g e | 2 Abstract The array of publications relating to the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921) has, generally speaking, neglected the contributions of less active counties. As a consequence, the histories of these counties regarding this important period have sometimes been forgotten. With the recent introduction of new source material, it is now an opportune time to explore the contributions of the less active counties, to present a more layered view of this important period of Irish history. County Kilkenny is one such example of these overlooked counties, a circumstance this dissertation seeks to rectify. To gain a sense of the contemporary perspective, the first two decades of the twentieth century in Kilkenny will be investigated. Significant events that occurred in the county during the period, including the Royal Visit of 1904 and the 1917 Kilkenny City By-Election, will be examined. Kilkenny’s IRA Military campaign during the War of Independence will be inspected in detail, highlighting the major confrontations with Crown Forces, while also appraising the corresponding successes and failures throughout the county. The Kilkenny Republican efforts to instigate a ‘counter-state’ to subvert British Government authority will be analysed. In the political sphere, this will focus on the role of Local Government, while the administration of the Republican Courts and the Republican Police Force will also be examined. -

Doing Local History in County Kilkenny: an Index

900 LOCAL HISTORY IN COLTN':'¥ PJ.K.T?tTNY W'·;. Doing Local History in County Kilkenny: Keeffe, .James lnistioge 882 Keeffe, Mary Go!umbkill & CourtT'ab(\.~(;J 3'75 An Index to the Probate Court Papers, Keefe, Michael 0 ........ Church Clara ,)"~,) Keeffe, Patrick CoJumkille 8'3(' 1858·1883 Keeffe, Patrick Blickana R?5 Keeffe, Philip, Ca.stJt! Eve B?~~ Marilyn Silverman. Ph,D, Keely (alias Kealy), Richard (see Kealy above) PART 2 : 1- Z Kiely .. James Foyle Taylor (Foylatalure) 187S Kelly, Catherine Graiguenamanagh 1880 Note: Part 1 (A . H) of this index was published in Kelly, Daniel Tullaroan 187a Kilkenny Review 1989 (No. 41. Vol. 4. No.1) Pages 621>-64,9. Kelly, David Spring Hill 1878 For information on the use of wills in historical rel,e2lrch, Kelly, James Goresbridge 1863 Kelly, Jeremiah Tuliyroane (T"llaroar.) 1863 the nature of Probate Court data and an explanation Kelly, John Dungarvan 1878 index for Co. Kilkenny see introduction to Part 1. Kelly, John Clomanto (Clomantagh) lS82 Kelly, John Graiguenamanagh !883 Kelly, John TulIa't"oan J88; Kelly, Rev. John Name Address Castlecomer ~883 Kelly, Martin Curraghscarteen :;;61 Innes. Anne Kilkenny Kelly, Mary lO.:· Cur,:aghscarteei'. _~; .... I Tl'win, Rev. Crinus Kilfane Gl.ebe Kelly, Michael 3an:,"~uddihy lSS~) Irwin, Mary Grantsborough ' Kelly, Patrick Curraghscarteen 1862 Izod, Henry Chapelizod House" . (\,~. Kelly, Patrick Sp";.llgfield' , 0~,,j !zod, Mary Kells HOllse, Thomastown Kelly. Philip Tul!arcar.. ':'!}S5 Izod, Thomas Kells Kelly, Richard Featha:ilagh :.07'i Kelly, Thomas Kilkenny 1.:)68 Jacob, James Castlecomer Kelly, Thomas Ir.shtown" :874 ,Jacob, Thomas J. -

090151B2803ee5bc.Pdf

For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. EPA Export 25-06-2011:03:48:08 For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. EPA Export 25-06-2011:03:48:08 For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. EPA Export 25-06-2011:03:48:08 Kilkenny County Council, Mooncoin Agglomeration WS - Water Quality Monitoring - WW - Discharge License - WW208 - Mooncoin Kilkenny County Council Water Services Authority County Hall, John Street, Kilkenny Tel: 056 7794050 Fax: 056 7794069 E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: www.kilkennycoco.ie For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. WS - Water Quality Monitoring - WW - Discharge License - WW208 - Mooncoin Waste Water Discharge Licence Attachments Page 1 EPA Export 25-06-2011:03:48:08 Tracking Revisions Revision Date Reason No. Section F Revised. Replaced in Full. A June 2011 Section G Revised. Replaced in Full. For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. EPA Export 25-06-2011:03:48:08 Kilkenny County Council, Mooncoin Agglomeration WS - Water Quality Monitoring - WW - Discharge License - WW208 - Mooncoin Contents: Section A Attachments..................................................................................4 Non-Technical Summary....................................................................................................4 A.1 Introduction ...................................................................................