Stone Fruit IPM for Beginners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BELLA SUN PEACOTUM July 15 - 25 Excellent Sorbet

BELLA SUN PEACOTUM July 15 - 25 excellent sorbet. We have a recipe. An interspecific apricot bred by Zaiger Genetics. FLAVOR PUNCH PLUERRY Sept 5 - 15 Both apricot and plum flavors are well represented Small to medium size with a red exterior, and bright in a single fruit. Good flavor balance with sweet and orange flesh. Excellent tropical punch flavor. plenty of tartness, and plum flavor. Outstanding. FLAVOR ROUGE PLUOT June 15 - 25 CANDY HEART PLUERRY August 15 - 25 Attractive red skin, and very sweet flavor. An Plum/Cherry cross. Dark red skin and speckled outstanding early season selection. finish. Flesh is amber-red. Unique flavor. FLAVOR SUPREME July 10 - 20 CRIMSON ROYALE August 5 - 15 ‘Flavor Supreme’ is the earliest of the highly flavored ‘Crimson Royale’ from Zaiger Genetics is the finest pluots and ripens during ‘Blenheim’ apricot season. example of a pluot. It’s plummy, but the apricot Resembles a typical blood plum in appearance, but parentage is also well represented. Crimson,with has very little tartness at the skin. The dark red flesh orange flesh. Loads of juice. When fully ripe, it’s is juicy, sweet, and richly flavored. sweet with an outstanding complex flavor. FLAVOR TOP July 15 - 25 DAPPLE SUPREME July 5 – 15 ‘Flavor Top’ nectarine is one of the old standard One of the ‘Dapple Series’ of pluots created by commercial varieties but still impresses with its Zaiger Genetics. Modeled skin, dark red flavorful flavor. Yellow with a fair amount of blush. Sweet, flesh. tart, complex flavor and juicy texture. EBONY ROSE July 20 – 30 HONEY PUNCH August 5 - 15 Beautifully colored, dark red skin with matching An excellent introduction from Zaiger Genetics. -

Plums in the Home Garden

November 2015 Horticulture/Fruit/2015-07pr Plums in the Home Garden Michael Caron, Extension Horticulturist, Thanksgiving Point Taun Beddes, Extension Horticulturist, Utah County Brent Black, Extension Fruit Specialist Introduction ‘Stanley’. Good plum-type cultivars include ‘Damson’, ‘Green Gage’, and ‘Seneca’. Three types of plum are commonly grown in Utah: European, Japanese and American species. These Japanese Plums: Japanese plum trees (Prunus species vary in where they are successfully grown salicina) are more rounded and spreading than and for what the fruit will be used for. Before European plums. Many cultivars on the market planting in the home orchard, planning helps ensure today are Japanese-American hybrids. They success. The following provides useful information produce fruit that is juicy and fairly large. The concerning care and selection of plants the home plums are round and skin color can range from gardener should consider. yellow to red with some being almost black. The flesh of the fruit is yellow or red. Japanese plums Species and Cultivars are primarily consumed as a fresh fruit but they can European Plums: European plum (Prunus successfully be processed as jam, jelly or fruit domestica) trees are upright and somewhat vase- leather. (Olcott-Reid and Reid, 2007). Japanese shaped. Prunes are a type of European plum with a plums are grown in USDA Zones 5 to 9. Pollinizers higher sugar content, which makes the fruit more are necessary. Plant near another Japanese or suitable for drying. Prune-type plums have oval American cultivar to pollinize, as European Plum shaped fruit, blue or purple skin, and yellow flesh. -

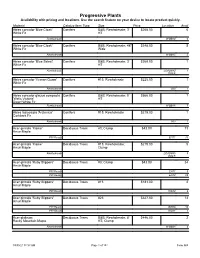

Onsite Availability by Location

Progressive Plants Availability with pricing and locations. Use the search feature on your device to locate product quickly. Material Catalog Item Type Size Price Location Avail Abies concolor 'Blue Cloak' Conifers B&B; Rewholesale; 3' $268.00 6 White Fir HT Rewholesale W BB14 6 Abies concolor 'Blue Cloak' Conifers B&B; Rewholesale; 48" $348.00 5 White Fir Wide Rewholesale W BB15 5 Abies concolor 'Blue Select' Conifers B&B; Rewholesale; 3' $268.00 1 White Fir HT Rewholesale LOADING 1 DOCK Abies concolor 'Vernon Quam' Conifers #15; Rewholesale $225.00 1 White Fir Rewholesale S03 1 Abies concolor glauca compacta Conifers B&B; Rewholesale; 5' $566.00 7 'Wells Victoria' HT Dwarf White Fir Rewholesale W BB16 7 Abies lasiocarpa 'Arizonica' Conifers #15; Rewholesale $219.00 1 Corkbark Fir Rewholesale S03 1 Acer ginnala 'Flame' Deciduous Trees #3; Clump $43.00 73 Amur Maple PPI Ready EH11 73 Acer ginnala 'Flame' Deciduous Trees #15; Rewholesale; $219.00 5 Amur Maple Clump Rewholesale LOADING 5 DOCK Acer ginnala 'Ruby Slippers' Deciduous Trees #3; Clump $43.00 34 Amur Maple PPI Ready EH11 5 PPI Ready EH12 29 Acer ginnala 'Ruby Slippers' Deciduous Trees #15 $181.00 2 Amur Maple PPI Ready WS12 2 Acer ginnala 'Ruby Slippers' Deciduous Trees #25 $327.00 13 Amur Maple PPI Ready WN09 12 PPI Ready WS01 1 Acer glabrum Deciduous Trees B&B; Rewholesale; 8' $446.00 2 Rocky Mountain Maple HT; Clump Rewholesale W BB26 2 09/30/21 01:53 AM Page 1 of 152 Form N/A Material Catalog Item Type Size Price Location Avail Acer griseum Deciduous Trees #15; Rewholesale; -

Evaluation of Fruit Cultivars

CORVINUS UNIVERSITY OF BUDAPEST FACULTY OF HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE MODERN HORTICULTURE EVALUATION OF FRUIT CULTIVARS Authors: Zsuzsanna Békefi (Chapter 3, 10) Géza Bujdosó (Chapter 9) Szilvia Kovács (Chapter 4, 7, 8) László Szalay (Chapter 5, 6) Magdolna Tóth (Chapter 1, 2) 1. Apple breeding trends and aims in the world. Successful and promising new cultivars Author: Magdolna Tóth 1.1. A brief history of apple cultivation and breeding Apple is one of the oldest fruit species. Apple residues were found e.g. at Jericho, in the Jordan valley and in Anatolia.Their origin is estimated to around 6500 BC, but it is impossible to identify from where these fruits got there.The most likely hypothesis is that the firts place of involving apple into cultivation was the territory between Caspian Sea and Black Sea, and apple was grown in this area already around 3000 BC. Actually, the discovery of grafting determined the further history of domestic apple. It gave not only the possibility for growers to reproduce a good quality tree, but it allowed the survival of the best ancient varieties as well. It is almost sure, that domestic apple arrived in Europe by Roman intermediation. In the 3rd century, the Romans established the first plantations in the territory of the present France, Spain and Great-Britain. In later centuries, some emperors (e.g. Charles the Great) and mostly religous orders had a great role in the preservation and renewal of apple cultivation. The widespread distribution of apple cultivation began in the 12th century. The first named cultivars appeared at this time, and according to the propagation possibilities of the age, the seeds of these varieties reached all places of the expanding world. -

Introgression of Prunus Species in Plum

Introgression of Prunus Plums have great potential as a species in Plum commercial crop in regions outside of W. R. Okie California. The wide United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research range of native plum Service, Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, species provides an 21 Dunbar Road, Byron, GA untapped source of genetic material. Results from hybridizations are “ ntrogression” is a big word meaning Origin introduction of the genes of one very unpredictable. This Ispecies into the gene pool of another. The ancestors of what we call paper describes some of This transfer can be a one-time thing, or Japanese plums actually originated in Figure 18. Apple mosaic virus is common on the Fuji variety. Figure 19. Bridge grafting is used to overcome if one parent is much better than the other, China. The term “Japanese plum” this intriguing girdling caused by Valsa mali cankers. it may involve repeated backcrossing of originally was applied to Prunus salicina germplasm maintained an interspecific hybrid with one of its imported from Japan in the late 19th parents (generally the one with better century, but now includes all the fresh at Byron, GA., and In Shandong province, we noted We were surprised to see so few some differences of opinion, and many fruit). Within Prunus, plums have had the market plums developed by intercrossing summarizes our efforts that tree trunks and scaffold limbs were pests in the orchards that we visited. It “what if” questions. However, none of most extensive mixing and matching of various diploid species with the original severely affected by Botryosphaeria appears that pest control technology in us would deny that China and Chinese species. -

Plant Availability

Plant Availability Product is flying out the gates! Availability is current as of 4/11/20 and is subject to change without notice. Call us to place an order for pick up or discuss details about curbside, local delivery for the Clovis/Fresno area. 559-255-6645 Or visit us! Our outdoor nursery is located on 10 acres at 7730 East Belmont Ave Fresno, CA. 93737 Availability in alphabetical order by botanical name. Common Name Botanical Name Size Loc. Avail Retail Glossy Abelia Abelia G Compacta Variegata * #5 R280A 15 $ 24.99 Confetti Abelia Abelia G Confettii #5 RETAIL 7 $ 28.99 Glossy Abelia Edward Goucher Abelia G Edward Goucher * #5 R280A 11 $ 19.99 'Kaleidoscope' Abelia Abelia Kaleidoscope Pp#16988 * #3 RET 1 $ 29.99 Passion Chinese Lantern Abutilon Patio Lantern Passion 12 cm R101 170 $ 7.99 Bear's Breech Acanthus mollis #5 R340B 30 $ 23.99 Trident Maple Acer Buergerianum #5 R424 3 $ 36.99 Miyasama Kaede Trident Maple Acer Buergerianum Miyasama Kaede #15 R520B 1 $ 159.99 Trident Maple Acer Buergerianum Trident #15 R498 3 $ 89.99 Trident Maple Acer Buergerianum Trident #15 R442 5 $ 89.99 Autumn Blaze Maple Acer Freemanni Autumn Blaze 24 box R800 2 $ 279.00 Autumn Blaze Maple Acer Freemanni Autumn Blaze #15 R442 3 $ 84.99 Autumn Blaze Maple Acer Freemanni Autumn Blaze 30 box R700 4 $ 499.00 Autumn Blaze Maple Acer Freemanni Autumn Blaze #5 R425 19 $ 39.99 Autumn Fantasy Maple Acer Freemanni Autumn Fantasy #15 R440 6 $ 84.99 Ruby Slippers Amur Maple Acer G Ruby Slippers 24 box R700 12 $ 279.00 Flame Maple Multi Acer Ginnala Flame Multi 30 box R700 2 $ 499.00 Flame Amur Maple Acer Ginnala Flame Std. -

Testing and Evaluation of Plum and Plum Hybrid Cultivars Jerome L

Testing and Evaluation of Plum and Plum Hybrid Cultivars Jerome L. Frecon and Daniel L. Ward New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, Rutgers University Introduction & Methods these cultivars are commonly called prunes. A botanical species, Prunus insititia or damson plum, is one of these This report is a continuation of plum, and cultivars. Varieties of the American, or wild, plum grow interspecific hybrids research first started by the on spreading trees and produce small, round fruit of senior author in 1989 and continued through 2011. various colors. These later two species have not been The Japanese type plum varieties adapted to the extensively evaluated in New Jersey and thus will not milder temperate climates of the Northeastern US be discussed in this report. are of great diversity. Many of these plum varieties are the result of interspecifi c hybridization. Most Varieties plums described as Japanese are the result of crosses of the Japanese plum, Prunus salicina, with the The Japanese type varieties grown on available American plum, Prunus americana, or the Apricot rootstocks are generally short-lived and relatively plum or Simon plum, Prunus simonii. More recently unproductive (there are exceptions). The trees are easily the Chickasaw plum, Prunus angustifolia, has been stressed by many of the same problems affecting peach used by southern breeders to improve adaptability. trees, namely winter injury, spring frost, moisture stress, Generally, the Japanese type plum varieties grow on nematodes, root rots, and short life. Some Japanese upright spreading, or spreading to drooping trees and varieties also experience latent incompatibility with produce round to heart-shaped fruit (pronounced apex) available rootstocks and decline slowly. -

Plum Breeding Worldwide

Plum Breeding Worldwide W.R. Okie1 and D.W. Ramming2 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. Prunus domestica, Prunus salicina SUMMARY. The status of plum breeding around the world is reviewed. Two distinct types of plums are grown: Japanese-type shipping plums (mostly diploid hybrids of Prunus salicina Lindl. with other species) such as are grown in California, and hexaploid or “domestica” plums (P. domestica L.), which have a long history in Europe. In recent years there has been a resurgence of plum breeding outside the United States. lums are native across much of the temperate area of the world. In most areas early inhabitants long ago selected superior indi- Pviduals of their local species. As Prunus breeders have made progress in improving plum quality and productivity, this native germplasm has been replaced by hybrid clones more suited to modern agriculture. Most plums in commercial production today are classified as Japanese (diploid) or European (mostly hexaploid) types. Japanese plums The ancestors of what we call Japanese plums actually originated in China. The term Japanese plum originally was applied to Prunus salicina (formerly P. triflora Roxb.) but now includes all the fresh- market plums developed by intercrossing various diploid species with the original species. These plums were initially improved in Japan and later, to a much greater extent, in the United States. Production in the United States is concentrated in California. Historical background Fortunately for the breeder, there are vast plum genetic resources although often they are not readily available (Okie and Weinberger, 1996; Ramming and Cociu, 1990). Prunus salicina cultivation goes back several thousand years in China (Yoshida, 1987) but plum has never been as commercially or culturally important in China as peach [P. -

Segregation of Plum and Pluot Cultivars According to Their Organoleptic Characteristics Carlos H

Postharvest Biology and Technology 44 (2007) 271–276 Segregation of plum and pluot cultivars according to their organoleptic characteristics Carlos H. Crisosto a,∗, Gayle M. Crisosto a, Gemma Echeverria b, Jaume Puy c a Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA1 b Centre UdL-IRTA, Rovira Roure, 191, Lleida 25198, Spain c Departament de Qu´ımica, Rovira Roure, 191, Lleida 25198, Spain Received 19 June 2006; accepted 9 December 2006 Abstract Cultivar segregation according to the sensory perception of their organoleptic characteristics was attempted by using trained panel data evaluated by principal component analysis of 12 plum and four pluot cultivars as a part of our program to understand plum minimum quality. The perception of the four sensory attributes (sweetness, sourness, plum flavor intensity, plum aroma intensity) was reduced to three principal components, which accounted for 98.6% of the variation in the sensory attributes of the tested cultivars. Using the Ward separation method and PCA analysis (PC1 = 49.8% and PC2 = 25.6%), plum and pluot cultivars were segregated into groups (tart, plum aroma, and sweet/plum flavor) with similar sensory attributes. Fruit source significantly affected cultivar ripe soluble solids concentration (RSSC) and ripe titratable acidity (RTA), but it did not significantly affect sensory perception of plum flavor intensity, sourness, sweetness, and plum aroma intensity by the trained panel on fruit harvested above their physiological maturity. Based on this information, we recommend that validation of these organoleptic groups should be conducted using “in store” consumer tests prior to development of a minimum quality index within each organoleptic group based on ripe soluble solids concentration (RSSC). -

Plantlist Master 12 18 09

Fruit Berries--Blackberry Rubus x Apples Cane berries are very easy, vigorous, semi-climbing or Malus sprawling plants. Plant near a fence so you can tie them up, Trees range from dwarf to very large. Most are narrow and or install a double wire system for training. Otherwise they upright. White to pale pink flowers are showy in late March will trail and root and form a dense briar patch. - early April. Fruit is along last year’s growth. Prune this to the ground Fruit on short spurs which take 3 - 4 years to form. after fruit is done, allowing new shoots for next season. Prune for size control, remove suckers and crossing Water well until fruit is done; then drought tolerant. branches. Boysenberry, thornless Tolerant of heavy soils, drought, or lawn watering. Very large fruit, very productive. Reddish-black fruit. Anders Apple Sweet and tart all-purpose berries. Midseason. Medium to large. Greenish-yellow base overlaid with generous Loganberry, thornless red striping. Crisp, white flesh is sweet with some tang, flavorful. Excellent for eating, drying, baking and cooking. Lighter red and tangier than Boysen, otherwise very Eaten on the green side, reminds you of Granny Smith. Eaten similar. Excellent variety. June. more ripe, reminds you of a Fuji apple. [LE Cooke description] Marion Berry Said to be codling moth resistant (?). Firm fruit holds its shape in cooking. Blackberry class. Braeburn Apple Rich flavor. June. Late season, crisp and tangy, similar to Granny Smith Olallie Berry but richer flavor. Excellent keeper. Green with dark red Black, shiny berries with ‘wild blackberry’ flavor. -

Varieties of Plums. Hybrids Are Not Gmos

Aprium® - a cross between an apricot and a plum. Prunus is a big genus that includes cherries, ‘Flavor Delight’ Looks like an apricot, but with extra flavor boost from the plum. Self- fertile, but will bear more heavily with an apricot for company. Note that it is an early plums, peaches and nectarines, apricots, and bloomer, so bloom may be damaged by late frosts. even non-edible ornamental trees and shrubs. These species most often reproduce Cherry-plum – is actually the common name of one of the parent species (Prunus cerasifera), which bears small round plum-type fruits. These hybrids include P cerasifera and within their own kind, but some species Japanese plums in a productive tree that can handle wet springs. They pollinize each other; cross more readily than others, and many plant both varieties. hybrids have been in cultivation for 'Delight' – Dark skin and golden, clingstone, tangy flesh. hundreds of years, like some of our familiar 'Sprite' – Dark skin and golden, freestone, sweet flesh. varieties of plums. Hybrids are not GMOs. Nectaplum® – nectarine and plum cross to make a very ornamental tree with big pink Adventurous growers (in the case of the flowers. below, the Zaiger family of California) have 'Spice Zee' looks like a nectarine, but has flavor traits of both parents. Self-fertile. been working on creating new hybrids that Pluerry™ – you might have guessed, these combine plums and sweet cherries for a fruit combine familiar characteristics into that’s between those in size, generally prolific, and with intriguing flavor combinations. interesting new taste sensations, so if you’re 'Candy Heart' Dark red skin, red flesh, ripe around August. -

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL RECORD. Autkors and Societies Are Requested to Forward Ntelr Works to Tke Editors As Soon As Publisked

J,.uary--Marc ,ss.] PS l'Ctt1. [3675-3683] 255 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL RECORD. Autkors and societies are requested to forward Ntelr works to tke editors as soon as publisked. Tke date of tublication, given in brackets [], marks tke time work was received, unless an earlier date of ublication is known to recorder or editor. Unless otkerwise slated eack record is made directly from tke work tkat is noticed. A colon after initial designates tke most common given name, as: A: Augustus; B: Ben- /amin; C: Ckarles; D: David; E: Edwar@ F: Frederic; G: George; It: Henry; I: Isaac; : okn; K: Ifarl; L: Louis; 2V[: Mark; 2V: Nickolas; O: Otto; t: Peter; R: Rickard: S: Samuel; T: Tkomas; W: Villiam. Tke initials at tke end of eack record, or note, are tkose of tke recorder. Corrections of errors and notices o omissions are solicited. Anderson, Joseph, jr. Urticating properties Briggs, T. R. Archer. On the fertilization of of lepidoptera. (Entomologist, Feb. 885, the primrose ()6rlmula vulgaris, Huds.). v. 8, p. 43-45.) (Journal of botany, 87o, v. 8, p. 9o-9.) Discussion of stinging hairs of larvae of bomb.ycidae; The writer does not agree with C Darwin in his "On quotation of the part of G: Dimmock's On the specific dfferences between primula veris, Br. FI., glands which open externally insects" (Psyche, t0. vularis, Br. FI., and/, elatior, Jacq (Journ. Sep.-Oct. xSSe [x Mar. x884], 3, P. 387-4o)[ Rec., e985] Linn. Sot., Bot., 9 Mar. x868, o, p. 437-454) [Rec., which pertains to this subject. G: D.