NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Pain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Creation of Neuroscience

The Creation of Neuroscience The Society for Neuroscience and the Quest for Disciplinary Unity 1969-1995 Introduction rom the molecular biology of a single neuron to the breathtakingly complex circuitry of the entire human nervous system, our understanding of the brain and how it works has undergone radical F changes over the past century. These advances have brought us tantalizingly closer to genu- inely mechanistic and scientifically rigorous explanations of how the brain’s roughly 100 billion neurons, interacting through trillions of synaptic connections, function both as single units and as larger ensem- bles. The professional field of neuroscience, in keeping pace with these important scientific develop- ments, has dramatically reshaped the organization of biological sciences across the globe over the last 50 years. Much like physics during its dominant era in the 1950s and 1960s, neuroscience has become the leading scientific discipline with regard to funding, numbers of scientists, and numbers of trainees. Furthermore, neuroscience as fact, explanation, and myth has just as dramatically redrawn our cultural landscape and redefined how Western popular culture understands who we are as individuals. In the 1950s, especially in the United States, Freud and his successors stood at the center of all cultural expla- nations for psychological suffering. In the new millennium, we perceive such suffering as erupting no longer from a repressed unconscious but, instead, from a pathophysiology rooted in and caused by brain abnormalities and dysfunctions. Indeed, the normal as well as the pathological have become thoroughly neurobiological in the last several decades. In the process, entirely new vistas have opened up in fields ranging from neuroeconomics and neurophilosophy to consumer products, as exemplified by an entire line of soft drinks advertised as offering “neuro” benefits. -

Meeting of Research and Clinical Leaders, Advocates and Patients to Highlight the Need to Reinstate Spinal Cord Injury Research Funding in Nys

MEETING OF RESEARCH AND CLINICAL LEADERS, ADVOCATES AND PATIENTS TO HIGHLIGHT THE NEED TO REINSTATE SPINAL CORD INJURY RESEARCH FUNDING IN NYS NYS has a Unique Spinal Cord Injury Program (SCIRP) funded through a small surcharge on traffic ticket moving violations. Since 1998 SCIRP has provided 70 million dollars towards treatments for spinal cord injury. After 2010, this money raised for paralysis research has been diverted to other purposes. We come together to urge NYS to reinstate this essential funding stream. Location: Empire State Convention Center, Meeting Rooms 2 &3, S. Mall Arterial, Albany NY 12242 Time: 9am-5.30pm, INCLUDING PRESS CONFERENCE AT 1PM Registration Required: Email Event Coordinator Cindy Butler [email protected] call 518 694 8188 by February 11th Register Early, space limited. Wheelchair accessible. Lunch provided, donation for meeting, $40 suggested Directions and Parking: visit http://ogs.ny.gov/ESP/CCE PROGRAM 9.00-9.10am Welcome and Introduction- Raj Ratan, Burke Medical Research Institute 9.10-10.00am NYS Support of Spinal Cord Injury Research – Raj Ratan, Chair 9.10- Terry O’Neill, Constantine Institute– How SCIRP came to be 9.25- Lorne Mendell, Stony Brook University - Intro to SCI and The Success of SCIRP Investment 9.40- Raj Ratan, Burke Medical Research Institute - On the SCI Network 9.55-Questions – 5 mins 10.00-10.50am Neuroplasticity and Robotics for Functional Recovery–Jon Wolpaw, Chair – 10.00-Jon Wolpaw, Wadsworth Institute -H-Reflex Plasticity 10.15-Aiko Thompson, Helen Hayes Hospital- Using -

Schwab and Mendell Labs Share Honors

Winter 2014 Consortium Paper Year’s Best for Journal; Schwab and Mendell Labs Share Honors ecently, the European Journal of Neuroscience (EJN) selected its Best Publication Award for R2013, honoring a paper, “Combined delivery of Nogo-A antibody, Neurotrophin-3 and NMDA-NR2D subunits establishes a functional detour in the hemi - sected spinal cord,” published by lead author Lisa Schnell from the Martin Schwab lab in Zurich, work - ing in collaboration with Victor Arvanian, then a researcher at the Lorne Mendell lab at the State University of New York, Stony Brook. Both labs are members of the Reeve International Research Consortium on Spinal Cord Injury. In this joint effort, the authors found that treat - ment of paralyzed animals with anti-Nogo-A (to overcome myelin inhibition), in combination with genetically induced expression of Neurotrophin-3 (NT-3, to enhance nerve growth) and boosting a glutamate receptor subunit (to increase synaptic plasticity), created a functional “detour” around the injury site. This improved recovery of function in adult rats. Schnell and Arvanian accepted the award at a ceremony in Prague. Below, Schnell describes the combination study, and her career. I began my career as a hematologist and then I joined the Martin Schwab lab in Zurich where we worked exclusively on the spinal cord, trying to find a treatment. Lisa Schnell, Ph.D. The long-held dogma was that injury to the spinal cord cannot be repaired, that the central nervous system, as opposed to the peripheral nervous system, has no ability Inside to repair itself. This might be attributed to lack of troph - Scientist Paul Lu 3 ic or growth-promoting factors. -

Computational Functions of Neurons and Circuits Signaling Injury: Relationship to Pain Behavior

Computational functions of neurons and circuits signaling injury: Relationship to pain behavior Lorne M. Mendell1 Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY 11794 Edited by Donald W. Pfaff, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, and approved November 3, 2010 (received for review August 16, 2010) The basic circuitry of the “pain pathway” mediating transmission cording from a population of small-diameter axons with proper- of information from the periphery to the brain is well known, ties of nociceptors. It is now well established that nociceptors consisting of specialized sensory fibers known as nociceptors pro- are a distinct population of sensory fibers with unique physio- jecting to specific spinal cord neurons, which in turn project on to logical, anatomical, and chemical properties. However, as we the thalamus and cerebral cortex. Here we survey some of the shall see below, activation of nociceptors can be prevented from unique properties of these circuits, such as peripheral and central causing pain, and conversely, pain is reported in situations in sensitization, and the segmental and descending modulatory con- which nociceptors are not activated. trol of synaptic transmission. We also review evidence indicating The defining characteristic of nociceptors is their high thresh- dissociation between nociceptor activity and behavioral indica- old to natural stimulation of their receptive field. This has been tions of pain. Together, these considerations point to the need investigated mostly -

Chronic Neurotrophin-3 Strengthens Synaptic Connections to Motoneurons in the Neonatal Rat

8706 • The Journal of Neuroscience, September 24, 2003 • 23(25):8706–8712 Development/Plasticity/Repair Chronic Neurotrophin-3 Strengthens Synaptic Connections to Motoneurons in the Neonatal Rat Victor L. Arvanian,1 Philip J. Horner,2 Fred H. Gage,3 and Lorne M. Mendell1 1Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, New York 11794, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98104, and 3Laboratory of Genetics, The Salk Institute, La Jolla, California 92161 We report that neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), delivered chronically via fibroblasts implanted intrathecally into neonatal rats, can facilitate synaptic transmission in the spinal cord. A small collagen plug containing NT-3-secreting fibroblasts was placed on the exposed dorsal surface of the spinal cord (L1) of 2-d-old rats; controls received -galactosidase-secreting fibroblasts. After 6 hr to 12 d of survival, synaptic potentials (EPSP) elicited by two synaptic inputs, L5 dorsal root and ventrolateral funiculus (VLF), were recorded intracellularly in L5 motoneurons in vitro. Preparations treated with NT-3 implants exhibited enhanced monosynaptic synaptic transmission from both inputs,whichpersistedovertheentiretestingperiod.UnlikeacuteenhancementoftransmissionbyNT-3(ArvanianandMendell,2001a), the chronic effect could occur at connections not normally eliciting an NMDA receptor-mediated response at the time of NT-3 exposure. ϩ Using susceptibility to blockade of the NMDA receptor by Mg 2 and APV, we confirmed that chronic treatment with NT-3 did not enhance NMDA receptor activity at these connections. Cords treated with chronic NT-3 also transiently displayed polysynaptic compo- nents activated by VLF that were blocked by the NMDA receptor antagonist APV. -

ANNUAL REPORT Department of Physiology

ANNUAL REPORT Department of Physiology January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2013 Dr. John Orlowski Chair June 2014 Description of Unit The Department of Physiology is housed in the McIntyre Medical Sciences Building, but also includes faculty members in the Bellini Life Sciences Complex, the Goodman Cancer Centre and throughout the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) network and affiliated hospitals (Jewish General Hospital and Montreal Neurological Institute). The academic staff of the Department consists of 28 professors and 42 associate members and 2 adjunct professors. Several full‐time members have full cross‐appointments in other departments and all associate members have primary appointments with other departments at McGill (both basic and clinical). Adjunct professors hold full‐time appointments in other universities. These ties strengthen the teaching and supplement the expertise of the Department of Physiology and provide an important network of communication with other Departments within the university and with other universities. The expertise of our faculty currently spans not only the contemporary fields of neuroscience, immunology, endocrinology, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, and cell physiology, but also emerging multidisciplinary areas of physiology that incorporate mathematics, computational modeling, simulation, electrical and biomechanical engineering. The overarching mission of the Department is to foster an environment that facilitates research and scholarly activities aimed at developing a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of living systems ranging from the study of single molecules to integrated systems of the cell, organ and organism. An applied goal is to translate this knowledge into the creation of novel biomaterials, biomedical devices and artificial cells & organs for the betterment of human health. -

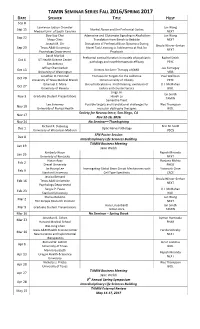

TAMIN SEMINAR SERIES FALL 2016/SPRING 2017 DATE SPEAKER TITLE HOST Sep 8 Lawrence Judson Chandler Jun Wang Sep 15 Alcohol Abuse and the Prefrontal Cortex Medical Univ

TAMIN SEMINAR SERIES FALL 2016/SPRING 2017 DATE SPEAKER TITLE HOST Sep 8 Lawrence Judson Chandler Jun Wang Sep 15 Alcohol Abuse and the Prefrontal Cortex Medical Univ. of South Carolina NEXT Doo-Sup Choi Adenosine and Glutamate Signaling in Alcoholism: Jun Wang Sep 22 Mayo Clinic Translation from Bench to Bedside NEXT Joseph M. Orr Disruptions of Prefrontal Brain Dynamics During Ursula Winzer-Serhan Sep 29 Texas A&M University Novel Task Learning in Adolescents at Risk for NEXT Psychology Department Psychosis David Morilak Prefrontal cortical function in models of psychiatric Rachel Smith Oct 6 UT Health Science Center pathology and novel therapeutic efficacy PSYC San Antonio Jeffrey Chamberlain Joe Kornegay Oct 13 Vectors for Gene Therapy of DMD University of Washington VIBS Jonathan D. Hommel Therapeutic Targets for the Addictive Paul Wellman Oct 20 University of Texas Medical Branch Dimensionality of Obesity PSYC Emanuel C. Mora Bat echolocation vs. moth hearing: evolution of U.J. McMahan Oct 27 University of Havana tactics and counter tactics BIOL Jingji Jin Ian Smith Nov 3 Graduate Student Presentations Hsueh Lu TAMIN Samantha Trent Lee Sweeney Possible targets and translational challenges for Wes Thompson Nov 10 University of Florida Health muscular dystrophy therapies BIOL Society for Neuroscience, San Diego, CA Nov 17 Nov 12-16, 2016 Nov 24 No Seminar—Thanksgiving Richard R. Dubielzig Erin M. Scott Dec 1 Optic Nerve Pathology University of Wisconsin-Madison VSCS SFN Poster Session Dec 8 Interdisciplinary Life Sciences Building TAMIN Business Meeting Jan 19 Jane Welsh Kimberly Nixon Rajesh Miranda Jan 26 University of Kentucky NEXT Hasan Ayaz Ranjana Mehta Feb 2 Drexel University PHEO Jin Hyung Lee Investigating Global Brain Circuit Mechanisms with Yoonsuck Choe Feb 9 Stanford University Cell Type Specificity CSCE Jessica Bernard Ursula Winzer-Serhan Feb 16 Texas A&M University NEXT Psychology Department Sergiu P. -

The Neurobiology of Pain,’’ Held December 11–13, 1998, at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center in Irvine, CA

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 96, pp. 7627–7630, July 1999 Colloquium Paper This paper is the introduction to the following papers, which were presented at the National Academy of Sciences colloquium ‘‘The Neurobiology of Pain,’’ held December 11–13, 1998, at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center in Irvine, CA. The neurobiology of pain RONALD DUBNER* AND MICHAEL GOLD Department of Oral and Craniofacial Biological Sciences, University of Maryland, School of Dentistry, Baltimore, MD 21201 This is a very exciting time in the field of pain research. Major and asked that we help him organize this colloquium. Soon advances are occurring at every level of analysis, from devel- after the program was approved and the date was set, John opment to neural plasticity in the adult and from the trans- learned that he had terminal cancer, and he died in September, duction of a noxious stimulus in a primary afferent neuron to 1997. He would have been very pleased by the depth and the impact of this stimulus on cortical circuitry. The molecular breadth of research covered as well as the lively interactions of identity of nociceptors, their stimulus transduction processes, all the participants. While John was remembered by many of and the ion channels involved in the generation, modulation, the speakers, Greg Terman, one of his former students, and propagation of action potentials along the axons in which delivered a moving and informative tribute (1). these nociceptors are present are being vigorously pursued. The colloquium got underway with a spirited discussion of Similarly, tremendous progress has occurred in the identifica- the role of ion channels in peripheral nerve, particularly their tion of the receptors, transmitters, second messenger systems, expression in nociceptors. -

Progress in Research

Summer 2010 Progress in Research very dark prognosis – how could there be any progress at all if there wasn’t even any- one really working on the problem? The Reeve Foundation helped to change all that. Today we have a sophisticated re- search program that incorporates multiple initiatives and institutions and approaches, a very full research continuum. We helped build the Foundation out to the point now where it will take basic research and move it down a translational pipeline. We put the infrastructure in place for developing our North American Clinical Trials Net- work, for example, and the NeuroRecov- ery Network. We have built what I consider to be a world-class organization. Q. So the Foundation is more broadly based than in the days when cure was the focus? A. Yes, that is right. Now, our efforts are based much more on our interaction with the community. We released our paralysis survey last year and found out there are many more people living with spinal cord Continued on page 4 Photo by Peter Billard Inside Jack Hughes, Foundation Board Chairman: A Family’s Commitment to the Reeve Mission Mendell Lab: ohn (Jack) Hughes is the Reeve Foundation, enabling the organization to Collaboration Foundation’s fifth Chairman of the significantly expand its research program. by Design Board since its inception in 1982 as Michael Hughes died in 2007. Greg Jthe American Paralysis Association remains active, chairing the Foundation’s (APA). He follows Hank Stifel, Christo- Connecticut Chapter. Jack Hughes, CEO Animal Core Lab: pher Reeve, Dana Reeve and Peter Kier- of Topcoder, the world’s largest competi- Building Capacity nan. -

NYS SCI Research Symposium 2018 the Rockefeller University Carson Family Auditorium

October 16 & 17, 2018 The Rockefeller University Carson Family Auditorium 1230 York Avenue, New York, New York NYS SCI Research Symposium 2018 The Rockefeller University Carson Family Auditorium PROGRAM COMMITTEE Donald S. Faber, Ph.D., Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Florence and Irving Rubenstein University, Professor Emeritus Bernice Grafstein, Ph.D., D.Sc.(hon.), Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Department of Brain and Mind Research Institute Lorne Mendell, Ph.D., Stony Brook University, Department of Neurobiology and Behavior Adam B. Stein, M.D., Chair and Professor, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra Northwell ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Andrea Garavelli, Director, Extramural Grants Administration, SCIRB Jeannine Tusch, Health Program Administrator, Extramural Grants Administration, SCIRB Special Thanks to our Sponsor: The Craig H. Neilsen Foundation is dedicated to research and programs to improve the quality of life for people living with spinal cord injury. TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM-AT-A-GLANCE 2 PROGRAM SCHEDULE, 10/16/18 3 PROGRAM SCHEDULE, 10/17/18 5 WELCOMING REMARKS 6 SPEAKER ABSTRACTS, 10/16/18 7 SPEAKER ABSTRACTS, 10/17/18 16 POSTER SESSIONS 22 ASSIGNMENTS 22 POSTER ABSTRACTS 26 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS 64 NOTES 70 SPONSORS 79 GENERAL INFORMATION All sessions will take place in the Carson Family Auditorium. MEALS All meals and the reception on Tuesday evening will take place in the lobby outside of the Carson Family Auditorium. POSTER SESSIONS Poster Sessions 1 & 2 will take place in the lobby outside of the Carson Family Auditorium. Presenters can set up their poster as early as 8am on the day of their scheduled session. -

Speaker Bios

Speaker Bios 5TH ANNUAL Meeting of the Minds Symposium Friday, October 31 • 8:30 am to 4 pm Keynote Speaker Ali R. Rezai, MD Dr. Rezai is Associate Dean of Neuroscience and the Director/CEO of the Comprehensive Brain and Spine Center at The Ohio State University. He is a board-certified neurosurgeon and renowned expert in the application of brain stimulation to treat movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, or tremor, as well as other conditions such as depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and chronic pain. He earned his medical degree from University of Southern California and completed neurosurgical training at New York University, University of Toronto and Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden. He has been the director of the Center for Functional and Restorative Neurosurgery at New York University Medical Center, and the director of the Center for Neurological Restoration, as well as the Jane and Lee Seidman Chair in Functional Neurosurgery at the Cleveland Clinic. He was named one of the best doctors in America in Castle and Connolly’s Guide to America’s Top Doctors for 2001-2014. Dr. Rezai is a Past President of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the North American Neuromodulation Society and the American Society of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery (ASSFN). He is also the recipient of the Bottrell Neurosurgical Award and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) William Sweet Investigator Award. Other Speakers Guy Schwartz, MD Dr. Schwartz is a board-certified neurologist, and Assistant Professor and Director of the Movement Disorders Section in the Department of Neurology at Stony Brook Medicine. -

Improving Outcome of Sensorimotor Functions After

F1000Research 2016, 5(F1000 Faculty Rev):1018 Last updated: 25 DEC 2016 REVIEW Improving outcome of sensorimotor functions after traumatic spinal cord injury [version 1; referees: 2 approved] Volker Dietz Spinal Cord Injury Center, Balgrist University Hospital, Forchstrasse 340, Zürich, CH-8008, Switzerland First published: 27 May 2016, 5(F1000 Faculty Rev):1018 (doi: Open Peer Review v1 10.12688/f1000research.8129.1) Latest published: 27 May 2016, 5(F1000 Faculty Rev):1018 (doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8129.1) Referee Status: Abstract Invited Referees In the rehabilitation of a patient suffering a spinal cord injury (SCI), the 1 2 exploitation of neuroplasticity is well established. It can be facilitated through the training of functional movements with technical assistance as needed and version 1 can improve outcome after an SCI. The success of such training in individuals published with incomplete SCI critically depends on the presence of physiological 27 May 2016 proprioceptive input to the spinal cord leading to meaningful muscle activations during movement performances. Some actual preclinical approaches to restore function by compensating for the loss of descending input to spinal networks F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned following complete/incomplete SCI are critically discussed in this report. from members of the prestigious F1000 Electrical and pharmacological stimulation of spinal neural networks is still in Faculty. In order to make these reviews as the experimental stage, and despite promising repair studies in animal models, comprehensive and accessible as possible, translations to humans up to now have not been convincing. It is possible that a combination of techniques targeting the promotion of axonal regeneration is peer review takes place before publication; the necessary to advance the restoration of function.