'Don Fabio' and the Taming of the Three Lions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infographic AMA 2020

Laureus World Sports Academy Members Giacomo Agostini Rahul Dravid Chris Hoy Brian O’Driscoll Marcus Allen Morné du Plessis Miguel Indurain Gary Player Luciana Aymar Nawal El Moutawakel Michael Johnson Hugo Porta Franz Beckenbauer Missy Franklin Kip Keino Carles Puyol Boris Becker Luis Figo Franz Klammer Steve Redgrave Ian Botham Emerson Fittipaldi Lennox Lewis Vivian Richards Sergey Bubka Sean Fitzpatrick Tegla Loroupe Monica Seles Cafu Dawn Fraser Dan Marino Mark Spitz Fabian Cancellara Ryan Giggs Marvelous Marvin Hagler Sachin Tendulkar Bobby Charlton Raúl González Blanco Yao Ming Daley Thompson Sebastian Coe Tanni Grey-Thompson Edwin Moses Alberto Tomba Nadia Comaneci Ruud Gullit Li Na Francesco Totti Alessandro Del Piero Bryan Habana Robby Naish Steve Waugh Marcel Desailly Mika Hakkinen Martina Navratilova Katarina Witt Kapil Dev Tony Hawk Alexey Nemov Li Xiaopeng Mick Doohan Maria Höfl-Riesch Jack Nicklaus Deng Yaping David Douillet Mike Horn Lorena Ochoa Yang Yang Laureus Ambassadors Kurt Aeschbacher David de Rothschild Marcel Hug Garrett McNamara Pius Schwizer Cecil Afrika Jean de Villiers Benjamin Huggel Zanele Mdodana Andrii Shevchenko Ben Ainslie Deco Edith Hunkeler Sarah Meier Marcel Siem Josef Ajram Vicente del Bosque Juan Ignacio Sánchez Elana Meyer Gian Simmen Natascha Badmann Deshun Deysel Colin Jackson Meredith Yuvraj Singh Mansour Bahrami Lucas Di Grassi Butch James Michaels-Beerbaum Graeme Smith Robert Baker Daniel Dias Michael Jamieson Roger Milla Emma Snowsill Andy Barrow Valentina Diouf Marc Janko Aldo Montano Albert -

Sir Alex Ferguson

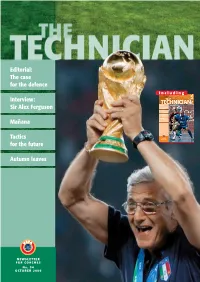

Editorial: The case for the defence Including Interview: Sir Alex Ferguson Mañana Tactics for the future Autumn leaves NEWSLETTER FOR COACHES N O .34 OCTOBER 2006 IMPRESSUM EDITORIAL GROUP Andy Roxburgh Graham Turner Frits Ahlstrøm PRODUCTION André Vieli Dominique Maurer Atema Communication SA Printed by Cavin SA COVER Having already won the UEFA Champions League with Juventus, Marcello Lippi pulled off a unique double in winning the World Cup with Italy this summer. (PHOTO: ANDERSEN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES) FABIO CANNAVARO UP AGAINST THIERRY HENRY IN THE WORLD CUP FINAL. THE ITALIAN DEFENDER WAS ONE OF THE BEST PLAYERS IN THE COMPETITION. BARON/BONGARTS/GETTY IMAGES BARON/BONGARTS/GETTY 2 THE CASE FOR THE DEFENCE EDITORIAL the French and, in the latter stages, FC Barcelona’s centre back Carles the Italians. On the other hand, the Puyol proved that star quality is not BY ANDY ROXBURGH, UEFA Champions League finalists the preserve of the glamour boys UEFA TECHNICAL DIRECTOR (plus seven other top teams) favoured who play up front. Top defenders and the deployment of one ‘vacuum their defensive team-mates proved cleaner’, as the late, great Rinus that good defensive play is a prerequi- Michels described the role. Interest- site to team success in top-level ingly, many of these deep-lying mid- competitions. Italy won the FIFA World Cup 2006 field players have become the initia- with a masterly display in the art of tors of the build-up play, such as The dynamics of football mean that defending. Two goals against, one Italy’s Andrea Pirlo. the game is always in flux. -

Germans Blast Capello Over International Recruitment Comments

Fabio Capello's recruitment comments not shared | Mail Online Pagina 1 Germans blast Capello over international recruitment comments By John Edwards Last updated at 7:32 PM on 30th December 2011 Fabio Capello was accused of getting his facts wrong and misunderstanding immigration on Friday as the German Federation hit back angrily at claims they were recruiting players by unfair means. Federation bosses reacted with dismay to the England manager's criticism of the way players from a Turkish background, such as Real Madrid's Mesut Ozil, have found their way into the Germany team. Still hurting: Fabio Capello dejected as England lose to Germany In an outspoken speech to an international sport conference in Dubai, the Italian claimed it was an unethical trend and called on UEFA president Michel Platini to halt the talent drain from poorer countries. Heritage question: Mesut Ozil He demanded football's rulers end the 'theft of talent' that goes on between national teams. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-2080424/Fabio-Capellos-recruitment-comments-shared.... 17/01/2012 Fabio Capello's recruitment comments not shared | Mail Online Pagina 2 But Federation sporting director Matthias Sammer insisted Germany were blameless and that Capello had failed to grasp how immigrants settling there deserved equal opportunities. Ozil was born in Gelsenkirchen, as a third-generation immigrant, and although his World Cup team-mates Lukas Podolski and Miroslav Klose were born in Poland, they moved to Germany as small children. 'Immigration is a social development that we react to in a proper way and I can assure Capello that we never entice players away from other countries,' said Sammer. -

Managing in Modern Football

Managing in Modern Football Considerations around leadership and strategies By Mark Miller Dissertation submitted in part of the requirements For the UEFA Pro License 2015/1017 Tutor; Stephen Grima Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 5 2 Leaders and Strategists: Born or Made? ............................................................ 8 2.1 Ends and Means: Thinking Strategically ......................................................... 10 3 Taking the Lead-and Defending it. .................................................................... 12 3.1 The Research Subjects: The Three Misters ................................................... 16 3.2 Seduction in the Fortress: Marco Baroni......................................................... 18 3.3 Winning, Planning and Creating: Howard Wilkinson ....................................... 23 3.4 Timing, Talking and Travelling: Roberto Martinez ........................................... 26 4 Conclusions and Recommendations. ............................................................... 28 4.1 Hearts, Minds and Memories .......................................................................... 29 4.2 Learning Outcomes ........................................................................................ 31 5 Bibliography ....................................................................................................... 34 Managing in Modern Football | 2 Acknowledgements The people who I -

Cristiano Ronaldo 'Best Player of the Year' At

Cristiano Ronaldo 'best player of the year' at Dubai football gala International Media Coverage | Web UAE| 26/1/2015 Dubai set to host fifth Globe Soccer Awards | The National Cristiano Ronaldo won the Globe Soccer Awards honour for Best Player in 2011. Photo Courtesy / Globe Soccer Awards Dubai set to host fifth Globe Soccer Awards December 14, 2014 Updated: December 14, 2014 04:57 PM Related Agency DUBAI // Some of the biggest names in world football will be gathered in Dubai on December 29 for the fifth Globe Soccer Awards, where the game’s best clubs, players, coaches, agents and media will be recognised across 15 categories. Real Madrid, Bayern Munich, Juventus, Ajax and Basel are locked in a five- Uefa president Michel way battle for “Club of the Year” in the event to be televised live by Abu Platini to kick off Dubai Dhabi TV from Atlantis, The Palm Dubai. Sports Conference Globe Soccer awards Other awards will go to Best Player of the Year, Best Coach, Best Agent of live on Abu Dhabi Sports the Year and Best Media Attraction in Football. Globe Soccer The event, formally known as the Globe Soccer Awards – presented by conference designed with Dubai clubs in mind Audi, is organised by Dubai Sports Council and BC Bendoni Communications. Radja Nainggolan fires AS Roma one point back “We will welcome to the red carpet great stars of our game,” said of Juve; AC Milan reach Tommaso Bendoni, Globe Soccer founder and organiser. sixth Arsenal spirits raised; The awards will come at a gala dinner at the conclusion of the second day Lampard lifts Man City – of the Globe Soccer annual meeting, dedicated to leading football EPL action in pictures operators. -

The Technician #44 (11.2009)

The Technician N°44•E 14.10.2009 13:34 Page 1 Editorial: The Best of Bobby Interview: Henk ten Cate Style, Stars and Simulation Theory and Practice An English Summer The Charter Accountant NEWSLETTER FOR COACHES N O 44 NOVEMBER 2009 The Technician N°44•E 14.10.2009 13:34 Page 2 IMPRESSUM EDITORIAL GROUP Andy Roxburgh Graham Turner PRODUCTION André Vieli Dominique Maurer Atema Communication SA Printed by Artgraphic Cavin SA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Monica Namy Stéphanie Tétaz COVER Coach Fabio Capello salutes David Beckham, John Terry and Wayne Rooney as The magic and the smile England qualify for the of Bobby Robson will always 2010 World Cup. be remembered. (Photo: Empics Sport) Getty Images 2 The Technician N°44•E 14.10.2009 13:34 Page 3 THE BEST OF BOBBY EDITORIAL But Bobby wasn’t just about enthusi- excited every time kick-off approaches. asm and energy. He was a highly com- Even when the opposition scores after BY ANDY ROXBURGH, petent coach and a wise council for 21 seconds, I still bounce back.” UEFA TECHNICAL DIRECTOR others. At a UEFA coaches conference same years ago, he described his Bobby’s record as a coach was out- approach to crisis management with a standing. Winning the UEFA Cup with story about his time at FC Barcelona. Ipswich Town was a remarkable achieve- On one occasion, his team were losing ment. As he himself said: “Taking heavily at home (4-1 down just after Ipswich from a “Cinderella” club to the I write this with a heavy heart, half-time) and the crowd were waving top level in Europe was fantastic. -

A Network-Based Assessment of the Career Performance of Professional Sports Coaches

Journal of Complex Networks (2021) 00, 1–25 doi: 10.1093/comnet/cnab012 Who is the best coach of all time? A network-based assessment of the career performance of professional sports coaches Sirag¸ Erkol and Filippo Radicchi† Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/comnet/article/9/1/cnab012/6251550 by guest on 25 April 2021 Department of Informatics, Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research, Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47408, USA †Corresponding author. Email: fi[email protected] Edited by: JoseM´ endez´ [Received on 18 December 2020; editorial decision on 10 March 2021; accepted on 22 March 2021] We consider two large datasets consisting of all games played among top-tier European soccer clubs in the last 60 years, and among professional American basketball teams in the past 70 years. We leverage game data to build networks of pairwise interactions between the head coaches of the teams and measure their career performance in terms of PageRank centrality. We identify Arsene` Wenger, Sir Alex Ferguson, Jupp Heynckes, Carlo Ancelotti and Jose´ Mourinho as the top 5 European soccer coaches of all time. In American basketball, the first 5 positions of the all-time ranking are occupied by Red Auerbach, Gregg Popovich, Phil Jackson, Don Nelson and Lenny Wilkens. We further establish rankings by decade and season. We develop a simple methodology to monitor performance throughout a coach’s career, and to dynamically compare the performance of two or more coaches at a given time. The manuscript is accompanied by the website coachscore.luddy.indiana.edu where complete results of our analysis are accessible to the interested readers. -

Fm Boss Tactics Book

FM Boss Tactical Guide Analysis of FM Boss Tactics 2012 4-1-3-2 of Cesare Prandelli Updated for FM 2012 The Reborn of Italian National Team Fratelli d'Italia, l'Italia s'e desta... Brother of Italy, Italy woke up... These are the first words of the Italian National Anthem. One country, 4 world cups numerous friends and enemies. But one thing the nobody can deny is the masterclass of Italian Coaches. Excellent in tactics, always extremely well prepared team and above all intelligence and flexibility. The last representative of the big Italian Coaching School is Claudio Cesare Prandelli. An ex player of Juventus, he played under the guidance of legendary Giovanni Trapattoni, winning recognition and trophies. A real fighter, despite he lost his wife in 2007 he continues to have the same desire and ambition for the game. Born in Orzinuovi in 19.8.1957 he was always the most hard working player in every club that he played. Outside of the pitch he is always smiley and humble. The Italian football federation after two failed choices trusted him till 2014. The immature experiments of Donadoni and the old time classic stubbornness of Lippi are over. Cesare keeps his nose down, he is not selling magic ideas and he is trusting a standard squad. He gives always chances to in-form players but he keeps on mind that Squadra Azzura represents whole nation so he needs to be serious and concentrated on what he does. He never speaks for the past and he rarely comments or compares opponents. -

February 2011

SOUTH EDITION - OCTOBER 2010 Issue 144 October 2010 www.thetraderonline.es • Tel 902733622 1 IInlandnland & CCoastaloastal FFREEREE / GGRATISRATIS rader Authorised Dealer VValenciaalencia - AlicanteAlicante Tel 902733633 T wwww.thetraderonline.es w w . t h e t r a d e r o n l i n e . e s SSOUTHOUTH EEDITIONDITION FEBRUARYFEBRUARY 22011011 Russell Grant’s Valentines Love Horoscopes 2011 HOW MUCH BUILDINGS INSURANCE COVER DO I ACTUALLY NEED? The UK’s legendary Astrologer Russell Grant has It’s a common question asked by most purchasers and revealed what the Stars have in store for all the Love existing owners when taking out insurance cover on Birds for 2011. Page 19 their home. page 16 Great for buying and selling stuff Be Aware of Changes to www.thewarehousespain.com Motorway Speed Cameras SPEED cameras are set to nail speed limits on motorways to SHARE SURFER drivers at slower paces after be raised to 140 and enforced. USB having been adjusted by the They argue that cars have bet- ROUTER DGT. ter braking systems and are Simple plug your USB The Dirección General de Trá- more technologically advanced dongle into the Router and fi co – the government’s road than when the 120-kilome- everyone in your home can traffi c department – says all tre speed limit was set in the connect wirelessly speed cameras have a margin 1970s, when few vehicles were See page 7 for error because the kilome- capable of travelling any faster. tre counters on cars are not Additionally, with a relatively low always entirely accurate. Until speed limit, drivers are more in- NEW RASTRO & now, radars were not activat- clined to fl out it, but are much ed on motorways until drivers more likely to respect a higher AUCTION NOW passed them at 140 kilometres limit. -

Fundación Magazine Nº 54

Nº 54 ● III-2016 'Plácido en el Alma' The concert contentssumario 3 SORPRENDE TE Publisher: Real Madrid “A perfect room, a superb breakfast and friendly Foundation. service with a smile. Always surprising”. Director of Communication: Antonio Galeano. Johann. Frankfurt. Publication: David Mendoza. Editors: Elena Vallejo, Javier Palomino and Madori Okano. Photography: Ángel Martínez, Helios de la Rubia, 4|Cover story 16|News Víctor Carretero, Pedro Castillo, Antonio Villalba, Real Madrid Heritage Centre and Real Madrid Foundation. Thanks to: Getty and Cordon Press. Publishing and distribution: EDICIONES REUNIDAS, S.A. GRUPO ZETA CORPORATE MAGAZINES c/ Orduña, 3 (3a planta). 28034 Madrid. 32|Interview Tel: 915 863 300. 24|Schools |Alberto Fernández (Endesa) Director of Corporate Publications: Óscar Voltas. Deputy Director: Antonio Guerrero. Coordinator: Julio Fernández. Editor-in-chief: Milagros Baztán. Writers: Elena Llamazares, Pablo Fernández and Isabel Tutor. Head of Design: Noelia Corbatón. Layout: Arantza Antero, Carlos F. García and Javier Sanz. Image Processing: David 34|Inspiring stories 42|Training Monserrat. Translation: David Nelson. Secretary: Antonia López. Head of Development: Carlos 40 Basketball 44 Heritage Silgado. Production: Jorge | |Real Madrid 1991-2000 Barazón and Iván Sánchez. | Printing: LITOFINTER. Legal deposit number: M-11535-2002. The Real Madrid Foundation accepts no responsibility for the opinions of the contributors. And also Campus 22 Volunteers 50 Always a pleasure nh-hoteles.es ADAPTACION JOHAN ING 210X280.indd 1 3/10/16 11:52 4 report report 5 'Plácido en el Alma' An The Real Madrid Foundation paid tribute to legendary opera singer and renowned Real Madrid fan, Plácido Domingo, for his 75th birthday with an extraordinary concert, Plácido en el Alma, with the participation of more historic than 30 locally and internationally renowned artists and groups. -

Capello, Il Divorzio E Servito Co Non Si Discute

Sport in tv MOTONAUTICA: Off shore Raitre, ore 15.40 PALLANUOTO: Finale due . Raitre, ore 16.25 SPORT: Studio sport Italial, ore 0 50 BASKET: NBaction . Tmc, ore 1.25 ^%^/1j^ ' V ^ IL FATTO. Polemico addio: «Non eravamo i piu forti». A giorni la firma con il Real Anche Seedorf arrlva a Madrid Sanz: «Accordo La «freddezza» con la Samp» dei giocatori: C'e«unaccordodprinciplo»fraReal MadrideSampdortaperi'acqinstoda «E bravo, ma...» parte del club spagrnio deH'attaccanteolMideK Clarence Seedorf. Uhaanmmdatoleri H OAL NOSTRO INVIATO pretiderrte del Real, Lorenzo Sanz, pariandoadunatnsmisslone • CARNAGO. Ciao ciao Capello. Sei stato un radk><onkalnSpagna,precisa»do buon allenatore, ci hai fatto vincere un sacco di anche die spera dl poterpagare la scudetti, ma nessuno ti rimpiangera. Tanti saluti, metadeHawmmaprevWadel buona fortuna, e un arrivederci con qualche pic parametro, die sarebbe di 9,6 colo rancore. mlUMldldollarl,doeM,5nilUardidi E il destino degli alienator!. Anche di quelli che Mre.«$eedorf-haaggHintoS*nz-e hanno riempito di coppe e scudetti le bacheche I'oWetUvoprlmarfodlFaNo delle ioro societa. Gli allenatori vanno, le squadre CapeHe-.HpresldtntedelReal, restano, Un luogocomune cui non sfugge neppu- lnfatU,MMihadusM>ul re Fabio Capello, tecnico pluriscudettato ma poco r/atrerimento del tecnico mManistaal amato dai giocatori per certe sue freddezze di ca- dub madrMeno. Seedorf, dal canto rattere. «Avendo fatto anch'io il calciatore, so che MM, ha attenuate che «del Real un allenatore non pud fare lamicone di tutti. Tan- Madrid non si e fatto avantl nessuno, to prima o poi qualcuno si scontenta sempre Me- neconme.iiecoftHmkiprociiratore. glio un rapporto professional improntato pero al Per ora vogUopetnare solo alia ia massimacorrettezza reciprocal partrUdldomeiilcacoirtrollMIUn». -

Soccer Book List

Soccer Book List 1. Brilliant Orange - The Neurotic Genius of Dutch soccer 2. Ajax Barcelona Cruyjff - The ABC of an Obstinate Maestro 3. Team Building - The Road to Success 4. Dutch Soccer Secrets 5. The Coaching Philosophies of Louis van Gaal and the Ajax Coaches 6. Coaching Soccer - The Official Coaching Book of the Dutch Soccer Association 7. Match Analysis and Game Preparation – Henny Kormelink 8. Playing Better Soccer is More Fun – Larry Paul 9. Ajax, The Dutch and The War - Simon Kuper 10. Ruud Gullit – The Portrait of a Genius 11. Jaap Stam: Head to Head 12. Guus Hiddink - Going Dutch 13. Martin Jol: The Inside Story 14. Louis van Gaal – Dutch Courage 15. O, Louis: in Search of Louis van Gaal 16. Silence and Speed –Dennis Bergkamp 17. Van Persie 18. My Turn – Autobiography – Johan Cruyjff 19. The Undutchables 20. Stuff Dutch People Like 21. Why The Dutch Are Different 22. Happiest Kids In The World 23. In The City Of Bikes - Amsterdam 24. Mourinho: Anatomy of a Winner 25. Mourinho: Autobiography – Made in Portugal 26. All the way José: The Inside Story of Chelsea 27. José Mourinho: Simply The Best 28. Manage Like Mourinho: Inside the Mind of the Special One 29. The Professor -- Arsene Wenger 30. Wenger – Interviews and Quotations 31. Wenger – Making of a Legend 32. Glorious Game – Arsene Wenger – Extra Time 33. Arsene Wenger – the Biography 34. Liverpool – The Miracle of Istanbul 35. Golden Past, Red Future: Liverpool FC – Champions of Europe 2005 36. Red Revival: Rafa Benitez’s Liverpool Revolution 37. Passing Rhythms – Liverpool Football Club 38.