Public Transit Finance in Vancouver, British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Version: January 24, 2020

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Version: January 24, 2020 January 30, 2020, 9:00AM to 10:30AM TransLink, Room 427/428, 400 – 287 Nelson’s Court, New Westminster, BC Chair: Mayor Jonathan X. Coté Vice-Chair: Mayor Jack Froese Note that times for each agenda item are estimates only. This meeting will be livestreamed and available afterwards on the Mayors’ Council’s Facebook page. 9:00AM 1. PRELIMINARY MATTERS 1.1. Adoption of agenda .......................................................................... Page 1 1.2. Approval of Minutes (December 12, 2019) ............................................... 2 9:05AM 2. PUBLIC DELEGATE PRESENTATIONS ................................................................ 7 9:35AM 3. REPORT OF THE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLANNING COMMITTEE 3.1. Broadway Subway Supportive Policies Agreement Monitoring Report ... 8 9:50AM 4. REPORT OF THE CHAIR 4.1. Update on Intermunicipal Business License for Ride-Hailing .................. 14 4.2. Next Steps on Surrey-Langley SkyTrain Project ....................................... 16 • Annex A: Surrey-Langley SkyTrain Business Case Summary ............... 17 • Annex B: Surrey-Langley SkyTrain Supportive Policies Agreement .... 39 • Annex C: Fraser Highway Corridor Land Use Planning ....................... 73 10:30AM 5. OTHER BUSINESS 5.1. Next Meeting – February 27, 2020 at 9:00AM 10:30AM 6. ADJOURN to closed session Public Meeting of the Mayors’ Council on Regional Transportation AGENDA PACKAGE, January 30, 2020 Page 1 MEETING OF THE MAYORS’ COUNCIL ON REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION -

Seismic Design of Bridges in British Columbia: Ten-Year Review

SEISMIC DESIGN OF BRIDGES IN BRITISH COLUMBIA: TEN-YEAR REVIEW Jamie McINTYRE Structural Engineer, Hatch Mott MacDonald, Vancouver Canada [email protected] Marc GÉRIN Consultant, Ottawa Canada [email protected] Casey LEGGETT Structural Engineer, Hatch Mott MacDonald, Vancouver Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT: Seismic design of bridges in British Columbia has evolved significantly in the last ten years. Developments have comprised three major changes in seismic design practice: (1) improved understanding of seismic hazard—including raising the design earthquake from a 475-year return period to 2475-year return period and better knowledge of the contribution of the nearby Cascadia subduction zone; (2) a shift to a performance-based design philosophy with emphasis on improved post-earthquake performance—including multiple service and damage objectives for multiple levels of ground motions; and (3) increased sophistication of seismic analyses—including both inertial analyses and analyses for liquefaction hazards. The result of these changes should be bridges that perform better and remain functional post-earthquake. These changes are expected to encourage alternatives to the traditional use of column plastic hinging, such as base-isolation. Over the last ten years, base-isolation has been used on few bridges in British Columbia—primarily retrofits of existing structures; however, given its ability to preserve post-earthquake functionality, base-isolation should be a serious consideration for any project. 1. Introduction – Evolution of Seismic Design Practice Seismic design of bridges in British Columbia has evolved significantly in the last ten years, going from a bridge design code using outdated principles to a state of the art new code that implements performance- based design. -

September 2017 Digital Edition

COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE | FRANCHISES | BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES $4.29 • SEPTEMBER 2017 • VOL32/9 RICHMOND | 12 BIG INDUSTRIAL BID “NOT SPEC” Richmond 170-acre development will start when first leases inked – and that will not be long PRE-SALES | 14 CRA PROBES CONDO FLIPS Canada Revenue Agency takes developer to court over assignment sales CONTENTS Full index 3 FFRANKLINRANKLIN JACKSONJACKSON Hotel towers 10 Industrial giant 12 MMARRIOTTARRIOTT Residential investing 14 Property taxes 16 TTOWERSOWERS IINTONTO B.C. report 18 Mortgage rates 20 CCENTRALENTRAL SSURREYURREY Done Deals 26 HHOTELSOTELS RISERISE ININ WESTWEST | 1100 PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT 40069240 0 9 0 6 0 3 5 8 1 8 2 9 1 9 MACDONALD COMMERCIAL Commercial Sales & Leasing, Property & Asset Management and Strata Management. macdonaldcommercial.com 604.736.5611 Listings on Page A4 & A5 A2 | LOWER MAINLAND WESTERNINVESTOR.COM | SEPTEMBER 2017 NEWLY RENOVATED FOR SALE - EAST VANCOUVER PRIME OCEANFRONT FOR SALE FOR SALE - SINGLE TENANT APARTMENT BUILDING BUILDING AND PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 38.4 - 78.4 ACRES INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY LIMERICK APARTMENTS - 5450 204TH ST, LANGLEY 1428 CHARLES STREET, VANCOUVER MARINER’S VILLAGE, SOOKE, BC BURKE MOUNTAIN, COQUITLAM 250 WINNIPEG STREET, PENTICTON, BC • Pad Development Opportunity • 41,382 sf / 0.95 acre property • Approximately 40,000 sf, two storey building • 8.63 acres of development land approved for • 2 lots: 38.4 and 40 acres • 1.43 acres site with net rentable area of 23,565 sf on 23,262 sf corner site mixed-use development • 3 storeys, 39 suites and 27,267 sf • Beautiful views • Net Operating Income $564,668 (as of 09/2017) of net rentable area • Located in Strathcona, walking distance to • Views of Sooke Harbour & the Olympic Mountains • Future residential development property • Long term lease • Asking Price $7,600,000 amenities of Venables and Commercial Drive • Serviced, zoned, marina leasehold included or ideal estate lots • Listing Price $9,800,000 • Asking $6,300,000 • Asking $3,500,000 per lot GREG MILES | CHRIS J. -

Container Capacity Expansion Plans at Pacific Coast Ports

TP 14710E Container Capacity Expansion Plans at Pacific Coast Ports Prepared for: Policy Research Branch Strategic Policy Directorate Policy Group Transport Canada By: Hanam Canada Corporation Victoria, BC January 2007 TP 14710E Container Capacity Expansion Plans at Pacific Coast Ports By: Hanam Canada Corporation 1165 Burdett Avenue Victoria, BC, V8V 3H3 250-381-6768 Web: www.hanamcanada.com Helmut G. Burke, P.Eng., MBA [email protected] January 2007 Container Capacity Expansion Plans at Pacific Coast Ports Hanam Canada Corporation January 2007 The Directory of Pacific Coast Container Ports, Terminals, and Services (TP 14711E) has been published as a companion document to this report. This report reflects the views of Hanam Canada Corporation only and does not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of Transport Canada. Neither Transport Canada, nor its employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of any information contained in this report, or process described herein, and assumes no responsibility for anyone's use of the information. Transport Canada is not responsible for errors or omissions in this report and makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of the information. Transport Canada does not endorse products or companies. Reference in this report to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by Transport Canada and shall not be used for advertising or service endorsement purposes. Trade or company names appear in this report only because they are essential to the objectives of the report. -

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Version: February 19, 2021

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Version: February 19, 2021 February 25, 2021, 9:00AM to 10:00AM Via Videoconference (live streamed to Mayors’ Council YouTube Channel) Chair: Mayor Jonathan X. Coté Vice-Chair: Mayor Jack Froese Note that times for each agenda item are estimates only. This meeting will be livestreamed and available afterwards on the Mayors’ Council’s YouTube channel. 8:50AM Technology Test: Please connect to the meeting early, by 8:50AM, to provide time to trouble-shoot any connection problems. 9:00AM 1. PRELIMINARY MATTERS 1.1. Adoption of agenda ........................................................................ Page 1 1.2. Approval of Minutes (January 28, 2021) ................................................. 2 9:05AM 2. PUBLIC DELEGATES ......................................................................................... 5 9:20AM 3. REPORT OF TRANSLINK MANAGEMENT ......................................... ON TABLE 9:30AM 4. REPORT OF THE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLANNING COMMITTEE 4.1 Update on Bus Priority Rapid Response .................................................. 6 4.2 Update on TransLink Tomorrow ............................................................. 15 9:45AM 5. REPORT OF THE FINANCE AND GOVERNANCE COMMITTEE 5.1. Surrey-Langley SkyTrain Project: a. Project Update ............................................................................ ORAL b. Supportive Policies Agreement ........................................................ 19 10:00AM 6. OTHER BUSINESS 6.1. Next Meeting (via videoconference) -

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Revised: July 22, 2019

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Revised: July 22, 2019 July 25, 2019, 9:00AM to 11:20AM TransLink, Room 427/428, 400 – 287 Nelson’s Court, New Westminster, BC Chair: Mayor Jonathan X. Coté Vice-Chair: Mayor Jack Froese Note that times for each agenda item are estimates only. This meeting will be livestreamed and available afterwards on the Mayors’ Council’s Facebook page. 9:00AM 1. PRELIMINARY MATTERS 1.1. Adoption of agenda ........................................................................ Page 1 1.2. Approval of Minutes (June 27, 2019) ...................................................... 2 9:05AM 2. PUBLIC DELEGATE PRESENTATIONS ............................................................ 10 9:35AM 3. REPORT OF THE CHAIR 3.1. Next steps on South of Fraser Rapid Transit ......................................... 11 • Annex A: Preliminary Business Case for Surrey Langley SkyTrain Project ................................................................................. 13 • Annex B: South of Fraser Rapid Transit Strategy Refresh ................ 27 10:25AM 4. REPORT OF THE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLANNING COMMITTEE 4.1. Transport 2050: Transportation Network Concept Development ........ 36 4.2. Burnaby Mountain Gondola .................................................................. 40 4.3. UBC Skytrain .......................................................................................... 47 4.4. George Massey Crossing Project Update ............................................. 50 10:55AM 5. REPORT OF THE FINANCE AND GOVERNANCE COMMITTEE -

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Revised: December 11, 2018

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Revised: December 11, 2018 December 13, 2018, 9:00AM to 11:15AM TransLink, Room 427/428, 400 – 287 Nelson’s Court, New Westminster, BC Chair: Mayor Jonathan X. Coté Vice-Chair: Mayor Jack Froese Note that times for each agenda item are estimates only. This meeting will be livestreamed and available afterwards on TransLink’s on Periscope and Facebook pages. 9:00AM 1. PRELIMINARY MATTERS 1.1. Adoption of agenda ..................................................................................... Page 1 1.2. Oath of office (Director LeBlanc) .......................................................................... 2 1.3. Approval of Minutes (November 15, 2018) ......................................................... 3 Time added: Updated report: 9:10AM 2. PUBLIC DELEGATES .................................................................................................... 15 10:00AM 3. REPORT OF THE CHAIR AND VICE-CHAIR 3.1. 2019 Work Plan .................................................................................................. 21 3.2. 2019 Committees ............................................................................................... 25 3.3. 2019 Meeting Schedule ...................................................................................... 30 10:20AM 4. REPORT OF TRANSLINK MANAGEMENT 4.1. Regional Transportation Strategy ...................................................................... 31 4.2. South of Fraser Rapid Transit Planning ............................................................. -

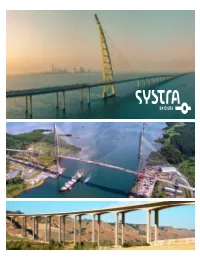

Dodam Bridge

A GLOBAL BRIDGE World’s Longest Sea Bridge NETWORK SYSTRA has been a world leader in the World’s Longest Floating Bridge fi eld of transportation infrastructure for 60 years. Bridges are a major product SHEIKH JABER AL-AHMAD AL-SABAH CAUSEWAY line and a cornerstone of our technical Kuwait MONTREAL excellence in providing safe, effi cient, PARIS SEOUL and economical solutions. SAN DIEGO EVERGREEN POINT FLOATING BRIDGE World’s Longest Span International Bridge Technologies joined Seattle, Washington Railway Cable-Stayed Bridge NEW DELHI SYSTRA in 2017. The two companies DUBAI have combined their complementary World’s Longest technical expertise to offer specialized Concrete Span engineering services in all facets of bridge TIANXINGZHOU BRIDGE design, construction, and maintenance. China World’s Fastest Design & SYSTRA’s Global Bridge Network consists Construction Supervision on any Metro Project of over 350 bridge specialists deployed 3rd PANAMA CANAL CROSSING worldwide, with Bridge Design Centers Colón, Panama World’s Longest located in San Diego, Montreal, São Paolo, Double Suspension Bridge SÃO PAOLO Paris, Dubai, New Delhi, and Seoul. MECCA (MMMP) METRO Saudi Arabia CHACAO BRIDGE BRIDGE DESIGN CENTERS Chacao, Chile • SERVICES • Tender Preparation • BIM / BrIM • Conceptual Design • Complex Drafting & Specialized Detailing • Pre-Bid Engineering • Realistic Graphics • Proposal Preparation - 3D Renderings - Visual Animation • Specifications Preparation - Construction Sequence Animation • Bids Analysis • Technical Assistance During Construction -

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Revised: April 27, 2021

PUBLIC MEETING AGENDA Revised: April 27, 2021 April 29, 2021, 9:00AM to 10:00AM Via Videoconference (live streamed to Mayors’ Council YouTube Channel) Chair: Mayor Jonathan X. Coté Vice-Chair: Mayor Jack Froese Note that times for each agenda item are estimates only. This meeting will be livestreamed and available afterwards on the Mayors’ Council’s YouTube channel. 8:50AM Technology Test: Members please connect to the meeting early, by 8:50AM, to provide time to trouble-shoot any connection problems. 9:00AM 1. PRELIMINARY MATTERS 1.1. Adoption of agenda .......................................................................... Page 1 1.2. Approval of Minutes (April 1, 2021) .......................................................... 2 9:05AM 2. PUBLIC DELEGATES ........................................................................................... 7 9:25AM 3. REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Report added 3.1. Federal and Provincial Budget Update .................................................... 62 9:35AM 4. REPORT OF THE FINANCE AND GOVERNANCE COMMITTEE 4.1. Low Carbon Fleet Strategy Implementation .............................................. 8 9:45AM 5. REPORT OF THE NEW MOBILITY COMMITTEE 5.1. Overview of Transport 2050 Phase 2 Public Engagement ....................... 15 9:55AM 6. OTHER BUSINESS 6.1. Next Meeting (via videoconference) – May 27, 2021 10:00AM 7. ADJOURN to closed session Note that Mayors’ Council members and Public Delegates will be participating via Zoom videoconferencing. Zoom connection information sent separately via e-mail. Public Meeting (via videoconference) of the Mayors’ Council on Regional Transportation REVISED AGENDA PACKAGE, April 29, 2021 Page 1 of 71 MEETING OF THE MAYORS’ COUNCIL ON REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION DRAFT PUBLIC MEETING MINUTES Minutes of the Public Meeting of the Mayors’ Council on Regional Transportation (Mayors’ Council) held Thursday, April 1, 2021 at 9:00 a.m. -

Industrial/Office Unit 2140-570 Sherling Place Port Coquitlam

FOR SALE | INDUSTRIAL/OFFICE UNIT 2140-570 SHERLING PLACE PORT COQUITLAM X 4,650 SF Office/warehouse unit X River Edge Business Park Location Highlights Situated in the heart of the Dominion Triangle area of Port Coquitlam, 570 Sherling Place X Concrete tilt-up with insulated exterior is located at the high exposure corner of Sherling Place and the Fremont Connector in the walls brand new River’s Edge Business Park. With close proximity to the Pitt River Bridge and the X Grade level loading Golden Ears Bridge to the east, the Coast Meridian Overpass to the west and being only X Approx. 22’ foot warehouse ceiling minutes from the Cape Horn Interchange, the Port Mann Bridge and Highway #1, River’s heights Edge Business Park offers a superb location for warehousing and distribution. Surrounded X 3-phase electrical power by the Fremont Village Shopping Centre, Mosaic’s Dominion residential development, X Five (5) Parking stalls with loading area Carnoustie Golf Club and recreational riverside parks and trails. River’s Edge Business Park X High exposure to Fremont Connector also offers unparalleled retail and lifestyle amenities. X High end architechually designed building X Fully finished offices over two levels with HVAC Ryan Barichello Chris McIntyre D 604.630.3371 C 604.889.4146 Personal Real Estate Corporation [email protected] D 604.630.3392 C 604.889.0699 [email protected] 475 West Georgia Street, Suite 800 | Vancouver, BC V6B 4M9 | 604.684.7117 | leevancouver.com FOR SALE | INDUSTRIAL/OFFICE UNIT 2140-570 SHERLING PLACE PORT COQUITLAM Zoning Strata Fees Asking Price M3 Industrial - Allows for clean manufacturiing, high tech, service $689.47 $1,930,000.00 and distribution use Taxes & Operating Costs (2019) Availability Features $16,540.94 Contact Agent X Fully finished offices over two levels with HVAC X Private offices, boardroom, lunchroom with kitchen and Floor Plans 100 WARE reception/showroom areas. -

An Ex Post Facto Evaluation of a Metro Vancouver Transportation Plan

An ex post facto Evaluation of a Metro Vancouver Transportation Plan by Devon Robert Farmer B. Eng., University of Victoria, 2010 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Urban Studies in the Urban Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Devon Robert Farmer 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Devon Robert Farmer Degree: Master of Urban Studies Title: An ex post facto evaluation of a Metro Vancouver Transportation Plan Examining Committee: Chair: Peter V. Hall Professor, Urban Studies Program Anthony Perl Senior Supervisor Professor, Urban Studies Program and Department of Political Science Karen Ferguson Supervisor Professor, Urban Studies Program and Department of History Clark Lim External Examiner Principal, Acuere Consulting Adjunct Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of British Columbia March 27, 2018 Date Defended/Approved: ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract Plans ought to be evaluated upon completion to determine their impacts and the reasons for success or failure. With this information, future planning efforts can be improved. Accordingly, this thesis offers an ex post facto evaluation of Metro Vancouver’s Transport 2021 medium-range transportation plan to determine its effectiveness and recommend how to improve future plans. In 1993, this plan recommended regional transportation policies and projects for the horizon year of 2006. Using a mixed-methods approach adapted from Laurian et al., the plan’s logic, implementation, and outcomes were examined, and factors affecting the results were considered. -

MACDONALD COMMERCIAL Commercial Sales & Leasing, Property & Asset Management and Strata Management

COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE | FRANCHISES | BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES $4.29 • OCTOBER 2017 • VOL32/10 LESLEY HEIEIS SSMARTERMARTER MMANAGEMENTANAGEMENT BBOOSTSOOSTS CCASHASH FFLOWLOW HOUSING CALL | 12 ‘SELL NOW, BUY TIER 1 PLAYERS IN THE WEST | 10 IN FOUR YEARS’ Trend-charter Dane Eitel says analytics point to a prolonged price slide SMALL-BIZ BLUES | 16 TAX TWEAKS SPOOK OWNERS Vancouver Board of Trade CEO Iain Black warns changes could be ruinous to some small businesses CONTENTS Full index 3 Property management 10 Residential outlook 12 Tax changes 16 New West commercial 20 Farmland sales 22 B.C report 24 Done Deals 26 PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT 40069240 1 0 0 6 0 3 5 8 1 8 2 9 1 9 MACDONALD COMMERCIAL Commercial Sales & Leasing, Property & Asset Management and Strata Management. macdonaldcommercial.com 604.736.5611 Listings on Page A4 & A5 A2 | LOWER MAINLAND WESTERNINVESTOR.COM | OCTOBER 2017 FOR SALE: 2 PROPERTIES WITH FOR SALE - EAST VANCOUVER PRIME OCEANFRONT FOR SALE FOR SALE - SINGLE TENANT 7 APARTMENT BUILDINGS BUILDING AND PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 38.4 - 78.4 ACRES INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY BAYVIEW CHATEAU - 1371 BLACKWOOD ST 1428 CHARLES STREET, VANCOUVER MARINER’S VILLAGE, SOOKE, BC BURKE MOUNTAIN, COQUITLAM 250 WINNIPEG STREET, PENTICTON, BC WHITE ROCK GARDENS - 14989 ROPER AVE WHITE ROCK, BC • Pad Development Opportunity • Approximately 40,000 sf, two storey building • 8.63 acres of development land approved for • 2 lots: 38.4 and 40 acres • 1.43 acres site with net rentable area of 23,565 sf on 23,262 sf corner site mixed-use development • Beautiful views • A total of 93 suites & approx.