Inherent Vice’S Epistemic Boundary Transgressions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

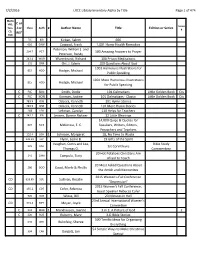

7/2/2016 LRCC Library Inventory Alpha by Title Page 1 of 474 C Or J

7/2/2016 LRCC Library Inventory Alpha by Title Page 1 of 474 Media VHS, C or Series Cass, Class Auth # J or Author Name Title Edition or Series # CD, REF DVD FIC KIR Kirban, Salem 666 610 CAW Cawood, Frank 1,001 Home Health Remedies Peterson, William J. and 204.7 PET 100 Amazing Answers to Prayer Peterson, Randy 242.4 WUR Wurmbrand, Richard 100 Prison Meditaitons 231 ORR Orr, J. Edwin 100 Questions About God 1001 Humorous Illustrations for 815 HOD Hodgin, Michael Public Speaking 1001 More Humorous Illustrations 815 HOD Hodgin, Michael for Public Speaking C FIC SMI Smith, Dodie 101 Dalmatians Little Golden Book Dis C FIC KOR Korman, Justine 101 Dalmatians - Classic Little Golden Book Dis 783.9 OSB Osbeck, Kenneth 101 Hymn Stories 783.9 OSB Osbeck, Kenneth 101 More Hymn Stories 268 LEH Lehman, Carolyn 110 Helps for Teachers C 242.2 JEN Jensen, Bonnie Rickner 12 Little Blessings 14,000 Quips & Quotes for 823 McK McKenzie, E. C. Speakers, Writers, Editors, Preaschers and Teachers 152.4 JOH 1 Johnson, Margaret 18, No Time to Waste 231.31 FLY Flynn, Leslie B. 19 Gifts of the Spirit Vaughan, Curtis and Lea, Bible Study 225 VAU 1st Corinthians Thomas O. Commentary 20 Hot Potatoes Christians Are 241 CAM Campolo, Tony Afraid to Touch 20 Most Asked Questions About 280 GOO Good, Merle & Phyllis the Amish and Mennonites 2015 Women's Fall Conference CD 616.85 SUL Sullivan, Rosalie "Depression" 2015 Women's Fall Conference, CD 155.2 COF Cofer, Rebecca Guest Speaker Rebecca Cofer 920 WIE Wiese, Bill 23 Minutes in Hell 23rd Annual International Women's -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. However, the thesis incorporates, to the extent indicated below, material already submitted as part of required coursework and/ or for the degree of: Masters in English Literary Studies, which was awarded by Durham University. Sign ature: Incorporated material: Some elements of chapter three, in particular relating to the discussion of teeth and dentistry, formed part of an essay submitted for my MA at Durham CniYersiry. This material has, however, been significantly reworked and re,,ised srnce then. Dismantling the face in Thomas Pynchon’s Fiction Zachary James Rowlinson Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex November 2015 i Summary Thomas Pynchon has often been hailed, by those at wont to make such statements, as the most significant American author of the past half-century. -

16 BRIAN JARVIS Thomas Pynchon Thomas Pynchon Is Perhaps Best

16 BRIAN JARVIS Thomas Pynchon Thomas Pynchon is perhaps best known for knowing a lot and not being known. His novels and the characters within them are typically engaged in the manic collection of information. Pynchon’s fiction is crammed with erudition on a vast range of subjects that includes history, science, technology, religion, the arts, and popular culture. Larry McMurtry recalls a legend that circulated in the sixties that Pynchon “read only the Encyclopaedia Britannica.”1 While Pynchon is renowned for the breadth and depth of his knowledge, he has performed a “calculated withdrawal” from the public sphere.2 He has never been interviewed. He has been photographed on only a handful of occasions (most recently in 1957). Inevitably, this reclusion has enhanced his cult status and prompted wild speculation (including the idea that Pynchon was actually J. D. Salinger). Reliable information about Pynchon practically disappears around the time his first novel was published in 1963. While Pynchon the author is a conspicuous absence in the literary marketplace, his fiction is a commanding presence. His first major work, V. (1963), has a contrapuntal structure in which two storylines gradually converge. The first line, set in New York in the 1950s, follows Benny Profane and a group of his bohemian acquaintances self-designated the “Whole Sick Crew.” The second line jumps between moments of historical crisis, from the Fashoda incident in 1898 to the Second World War and centers on Herbert Stencil’s quest for a mysterious figure known as “V.” Pynchon's second novel, The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), is arguably his most accessible work and has certainly been the most conspicuous on university syllabuses. -

South Orlando Baptist Church LIBRARY RECORDS by SUBJECT

South Orlando Baptist Church LIBRARY RECORDS BY SUBJECT Page 1 Friday, November 15, 2013 Find all records where any portion of Basic Fields (Title, Author, Subjects, Summary, & Comments) like '' Subject Title Classification Author Accession # Abandoned children Fiction A cry in the dark (Summerhill Secrets #5) JF Lewis, Beverly 6543 Abandoned houses Fiction Julia's hope (The Wortham Family Series #1) F Kelly, Leisha 5343 Abolitionists Frederick Douglass (Black Americans of Achievement) JB Russell, Sharman Apt. 8173 Abortion Fiction Choice summer (Nikki Sheridan Series #1) YA F Brinkerhoff, Shirley 7970 Shades of blue F Kingsbury, Karen 8823 Tilly : the novel F Peretti, Frank E. 6204 Abortion Moral and ethical aspects Abortion : a rational look at an emotional issue 241 Sproul, R. C. (Robert Charles) 1296 Abraham (Biblical patriarch) Abraham and his big family [videorecording] VHS C220.95 Walton, John H. 5221 Abraham, man of faith J221.92 Rives, Elsie 1513 Created to be God's friend : how God shapes those He loves 248.4 Blackaby, Henry T. 4008 Dragons (Face to face) J398.24 Dixon, Dougal 8517 The story of Abraham (Great Bible Stories) C221.92 Nodel, Maxine 3724 Abused children Fiction Looking for Cassandra Jane F Carlson, Melody 6052 Abused wives Fiction A place called Wiregrass F Morris, Michael 7881 Wings of a dove F Bush, Beverly 2498 Abused women Fiction Sharon's hope F Coyle, Neva 3706 Acadians Fiction The beloved land (Song of Acadia #5) F Oke, Janette 3910 The distant beacon (Song of Acadia #4) F Oke, Janette 3690 The innocent libertine (Heirs of Acadia #2) F Bunn, T. -

Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative

Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative Miles Taylor A Thesis in The Department of Film Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 2020 © Miles Taylor 2020 Signature Page This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Miles Taylor Entitled: Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative And submitted in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) Complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Examiner Luca Caminati Examiner Mary Esteve Supervisor Martin Lefebvre Approved by Marc Steinberg 2020 Rebecca Duclos Taylor iii Abstract Overwhelmed and Underworked: Inherent Vice, Aproductivity, and Narrative Miles Taylor This thesis proposes an artistic mode called aproductivity, which arises with the secular crisis of capitalism in the early 1970’s. It reads aproductivity as the aesthetic reification of Theodor Adorno’s negative dialectics, a peculiar form of philosophy that refuses to move forward, instead producing dialectics without synthesis. The first chapter examines the economic history aproductivity grows out of, as well as its relation to Francis Fukuyama’s concept of “The End of History.” After doing so, the chapter explores negative dialectics and aproductivity in relation to Adam Phillips’ concept of the transformational object. In the second chapter, the thesis looks at the Thomas Pynchon novel Inherent Vice (2009), as well as the 2014 Paul Thomas Anderson adaptation of the same name. -

MEDIA-2013 Book Festival Program

Jemmie Adams Mark Baird Running With No Feet – Parts 1 & 2 The Idiom Magazine & Idiom Anthologies Self-Published by Midnight Publishing, 2010 Self-Published by Piscataway House Publications, 2013 In Running With No Feet, Steve Birdoff's world changed the Mark Baird is a graduate student at William Paterson University second he discovered that he worked for a who began writing while getting his powerful sociopath. He soon finds himself undergraduate degree in English at Richard scrambling to protect what is left of his family Stockton College. In an attempt to get more while forging alliances and rediscovering his involved with the writing community, he humanity along the way. Now with Part 2, the began making a homemade publication, The episodic adventure becomes complete. Author Idiom Magazine, of his and others’ poetry that by Jemmie Adams also demonstrates his he distributed for free at readings. Turning his caring by designating part of the book magazines into actual books set the stage for proceeds to be donated to search for a cure in establishing Piscataway House Publications. autism and breast cancer research. Idiom Anthologies is a collection of haiku and other things. (www.theidiommag.com) Sylvie Bayeux / Loannis Tziligakis Ralph W. Baker, Jr. How Inner-City Kids from Medea: A Dance Performance with Narration Shock Exchange: Dancer / Actor Brooklyn Predicted the Great Recession and the Pain Ahead Self-Published by the New York Shock Exchange Originally from Chile, Sylvia Baeza is a multicultural and multifaceted artist who brings her keen synthetic power to her theatrical work, both as director, Ralph W. -

Chick Corea Trilogy

GRANDE SALLE PIERRE BOULEZ – PHILHARMONIE Lundi 2 mars 2020 – 20h30 Chick Corea Trilogy Programme CHICK COREA TRILOGY Chick Corea, piano Christian McBride, contrebasse Brian Blade, batterie FIN DU CONCERT (AVEC ENTRACTE) VERS 22H50. 4 Chick Corea TrilogyLe concert Le 26 janvier dernier, à Los Angeles, Chick Corea recevait le Grammy Award du meilleur album de jazz latino pour son disque Antidote, enregistré avec son groupe The Spanish Heart Band. Cinq ans auparavant, c’est avec deux Grammy Awards – récompense la plus enviée de l’industrie phonographique – que l’artiste était reparti de la cérémonie, le premier au titre du meilleur album de jazz instrumental, le second du meilleur solo de jazz improvisé. Ces deux trophées étaient décernés à Trilogy, triple album enregistré en public avec Christian McBride et Brian Blade, les musiciens avec lesquels il se produit ce soir. Il y a quelques mois, Chick Corea faisait paraître une suite à ce disque, tout simplement intitulée… Trilogy 2. Remportera-t-il, dans un an, un Grammy Award supplémentaire grâce à cet opus ? Ce ne serait jamais que le vingt-quatrième de sa carrière, ce qui le classerait définitivement parmi les musiciens les plus primés par la prestigieuse académie, tous genres confondus. Si les honneurs ne sont pas toujours la meilleure aune pour juger du talent d’un artiste, on ne fera pas à Chick Corea l’offense de contester le bien-fondé de tant de récompenses collectionnées au fil d’une carrière particulièrement dense. Depuis la fin des années 1960, ce pianiste est incontestablement l’un des plus influents et des plus prolifiques de sa généra- tion. -

A Deculturated Pynchon? Thomas Pynchon's Vineland and Reading In

A Deculturated Pynchon? Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland and Reading in the Age of Television Tobias Meinel ABSTRACT This essay examines Thomas Pynchon’s novel Vineland as a take on reading in the 1980s. Vineland’s suffusion with popular culture and television references has led many critics to focus on its shift in style and content and to read it either as “Pynchon Lite” or as a critical commen- tary on contemporary American culture. Few critics, however, have picked up on Pynchon’s sus- tained concern with creating reader-character parallels. Through the figure of Prairie Wheeler, Vineland presents us, I argue, with a sophisticated allegory about the entrapments of superficial reading. Representing what Judith Fetterley has termed the “resisting reader,” Prairie guides us through the 1980s Culture Wars in which reading had become a political issue. Under its sur- face, then, Vineland appears as a highly self-reflective novel that complicates cause and effect in contemporary discussions about reading, mass culture, and television. When Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland was published in 1990, the novel’s apparent difference from its predecessor Gravity’s Rainbow in style, content, and scope led to puzzled reactions. Was this what Pynchon had been working on for seventeen years? Was it a “breather between biggies,” as one critic suspected (Leonard 281)? Or did the novel’s infusion with popular culture simply constitute a lesser novel, a “Pynchon Lite” (Kakutani)? On the one hand, the story of aging hippie Zoyd Wheeler and his teenage daughter Prairie, who are looking for Zoyd’s ex-wife (and Prarie’s mother) Frenesi, a former Sixties radical who turned against her friends and ran away with federal prosecutor and bad guy Brock Vond, seemed much “more manageable” than the plot of Gravity’s Rainbow, as one critic put it (qtd. -

Music in Thomas Pynchon's Mason & Dixon

ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): John Joseph Hess Affiliation(s): Independent Researcher Title: Music in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon Date: 2014 Volume: 2 Issue: 2 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/75 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7766/orbit.v2.2.75 Abstract: Through Pynchon-written songs, integration of Italian opera, instances of harmonic performance, dialogue with Plato’s Republic and Benjamin Franklin’s glass armonica performance, Mason & Dixon extends, elaborates, and investigates Pynchon’s own standard musical practices. Pynchon’s investigation of the domestic, political, and theoretical dimensions of musical harmony in colonial America provides the focus for the novel’s historical, political, and aesthetic critique. Extending Pynchon’s career-long engagement with musical forms and cultures to unique levels of philosophical abstraction, in Mason & Dixon’s consideration of the “inherent Vice” of harmony, Pynchon ultimately criticizes the tendency in his own fiction for characters and narrators to conceive of music in terms that rely on the tenuous and affective communal potentials of harmony. Music in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon John Joseph Hess Few readers of Thomas Pynchon would dispute William Vesterman’s claim that “poems and particularly songs, make up a characteristic part of Pynchon’s work: without them a reader’s experience would not be at 1 all the same.” While Vesterman was specifically interested in Pynchon’s poetic practice, Pynchon’s fifty year career as a novelist involves a sustained engagement with a range of musical effects. Music is a formal feature with thematic significance in Pynchon’s early short fiction and in every novel from V. -

Album, and Travel Will Resume Soon

An Encouraging Equinox (3/20/21) After a long, gloomy year, John & Jessica are in high spirits at last. John is now a Grammy Award-winner, he’s previewing his new album, and travel will resume soon. John earned his Grammy as co-producer of James Taylor’s “American Standard” album. His own new album, “Better Days Ahead,” featuring songs written by Pat Metheny, will be released April 16. And his travel plans include long drives with Jess, which will always include a trip to the car wash. Soon a crocus will rear its beautiful head, the ice on the lake will be melted, and the car will be packed and ready to go, all because spring begins at the moment of the vernal equinox, Saturday morning at 5:37 EDT, and, of course, the COVID vaccine. James Taylor - My Blue Heaven (American Standard) Wynton Marsalis - How Are Things in Gloca Morra (Standard Time, Vol. 3: The Resolution of Romance) Johnny Frigo & Bucky & John Pizzarelli - Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me (Live from Studio A) Karrin Allyson - Mind on My Man (Wild for You) Jessica Molaskey - Everything Is Moving Too Fast (It's a Good Day) Frank Sinatra - It's Nice to Go Trav'ling (Come Fly With Me) George Lee Andrews, Margery Cohen - Travel (Starting Here Starting Now OC Sail Away: Why Do the Wrong People Travel - Noel Coward (Noel Coward Sings "Sail Away" and Other Coward Rarities) Queen Latifah - Poetry Man (Trav'lin' Light) Les Paul & Mary Ford - The World Is Waiting for the Sunrise (Best of the Capital Masters) Bill Evans - Spring Is Here (Bill Evans' Finest Hour) Chick Corea/Christian