A Harlot's Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Harlot's Progress Series 22 2.2.1

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit: Iain Bell’s A Harlot’s Progress: A Dramaturgical Analysis of the Journey from Engravings to Opera verfasst von Margarethe Satorius angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 581 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Mediengeschichte Betreut von: Ass.-Prof. Dr. Isolde Schmid-Reiter Diana Damrau as Moll Hackabout in Iain Bell and Peter Ackroyd’s A Harlot’s Progress: world premiere at Theater an der Wien, October 2013 (Image © Werner Kmetitsch) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. HISTORY OF THE PIECE 9 2.1. William Hogarth and British Capitalism of the Early 18th Century 10 2.1.1. Biography of the Artist 10 2.1.2. Development of a New British Capitalism 15 2.2. William Hogarth's A Harlot's Progress Series 22 2.2.1. Historical Influences 23 2.2.2. Adaptations of the Harlot Narrative 27 3. IAIN BELL’S A HARLOT’S PROGRESS OPERA 36 3.1. Conception and Realization 36 3.1.1. Theater an der Wien Commission 36 3.1.2. Transmedial Adaptation 38 3.2. Dramaturgy 43 3.2.1. Comedy 46 3.2.2. Tragedy 51 3.3. Music 61 3.3.1. Character 61 3.3.2. Correlation Between Structure, Character, and Setting 68 3.3.3. Dramaturgical Significance of Orchestral Silence 72 4. CRITICAL RECEPTION 76 APPENDICES 89 BIBLIOGRAPHY 169 Primary Sources 169 Secondary Sources 170 2 ABSTRACT 176 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG 177 CURRICULUM VITAE 178 3 Foreword In the autumn of 2013 I was fortunate to join the world premiere production of Iain Bell and Peter Ackroyd’s A Harlot’s Progress at the Theater an der Wien. -

NSF Programme Book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 1

two weeks of world-class music newbury spring festival 11–25 may 2019 £5 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 1 A Royal Welcome HRH The Duke of Kent KG Last year was very special for the Newbury Spring Festival as we marked the fortieth anniversary of the Festival. But following this anniversary there is some sad news, with the recent passing of our President, Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon. Her energy, commitment and enthusiasm from the outset and throughout the evolution of the Festival have been fundamental to its success. The Duchess of Kent and I have seen the Festival grow from humble beginnings to an internationally renowned arts festival, having faced and overcome many obstacles along the way. Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon, can be justly proud of the Festival’s achievements. Her legacy must surely be a Festival that continues to flourish as we embark on the next forty years. www.newburyspringfestival.org.uk 1 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 2 Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon MBE Founder and President 1935 - 2019 2 box office 0845 5218 218 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 3 The Festival’s founder and president, Jeanie Countess of Carnarvon was a great and much loved lady who we will always remember for her inspirational support of Newbury Spring Festival and her gentle and gracious presence at so many events over the years. Her son Lord Carnarvon pays tribute to her with the following words. My darling mother’s lifelong interest in the arts and music started in her childhood in the USA. -

Holiday Issue 2014 CUES

OPERAVolume 55 Number 03 | Holiday Issue 2014 CUES World Premiere Iain Bell and Simon Callow A CHRISTMAS CAROL DECEMBER 5, 7, 9, 11, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21 PATRICK SUMMERS PERRYN LEECH ARTISTIC & MUSIC DIRECTOR MANAGING DIRECTOR Margaret Alkek Williams Chair ADVERTISE IN OPERA CUES Opera Cues is published by Houston Grand Opera Association; all rights reserved. Opera Cues is produced by Houston Grand Opera’s Communications Department, Judith Kurnick, director. Director of Publications Laura Chandler Art Direction / Production Pattima Singhalaka Contributors Iain Bell Simon Callow Perryn Leech Myles Mellor For information on all Houston Grand Opera productions and events, or for a complimentary season brochure, please call the Customer Care Center at 713-228-OPERA (6737). Houston Grand Opera is a member of OPERA America, Inc., and the Theater District Association, Inc. Find HGO online: HGO.org facebook.com / houstongrandopera twitter.com / hougrandopera Readers of Houston Grand Opera’s Mobile: HGO.org Opera Cues magazine are the most desirable prospects for an advertiser’s message. LOYAL: 51 percent of readers have been reading Opera Cues for more than three years. DEDICATED: 42 percent of readers read the magazine from cover to cover. EDUCATED: More than 90 percent are college-educated, and 57 percent hold graduate degrees. SOCIAL: 44 percent patronize downtown restaurants when they go to a performance at Houston Grand Opera. For more information on advertising in Opera Cues, call Matt Ross at 713-956-0908. 2 | Opera Cues Holiday Issue 2014 www.HGO.org B:8.625” T:8.375” S:7.875” KEEPING ELITE PERFORMERS IN THE SPOTLIGHT. -

General Sponsor Intendant Roland Geyer

Intendant Roland Geyer General sponsor The Theater an der Wien receives subsidies A Wien Holding Company from the Cultural Department of the City of Vienna “BeautIFUL MUSIc…” To look for the greatest triumphs of opera means applying the epithets Igor Stravinsky set Hogarth’s series of pictures, The Rake’s Progress, to “genius” and “originality” to a musical event. Such triumphs often came music as the opera of the same name which created a furore and proved about by chance or were not recognised as such until favourable cir- a huge success when it was staged at the Theater an der Wien in 2008 cumstances arose centuries later that revealed their true quality. Take by Martin Kušej under the musical direction of Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Mendelssohn’s revival of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in the mid-nine- When the moralistic and strict judge John Gonson began a campaign teenth century, for example. Add to this the fact that before Mozart and against prostitution in the City of London, Hogarth was inspired to cre- Beethoven the creators of works of such specific evocative power were ate a second series, A Harlot’s Progress. The Theater an der Wien has not unanimously regarded as geniuses by their audiences. George Frid- now commissioned the renowned English dramatist Peter Ackroyd and eric Handel, for instance, still had to contend with derision, envy and the young English composer Iain Bell to write a new opera about the bankruptcy for years after his ground-breaking masterpiece, Messiah. story of a naïve country girl who falls into the clutches of a procuress Only at the end of his life was he feted as the nation’s composer, a sta- and is forced into prostitution. -

IO Recognised at the International Opera Awards and Announces

INDEPENDENT OPERA ANNOUNCES 2016 DIRECTOR FELLOWSHIP Polly Graham to direct Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s Simplicius Simplicissimus at Lilian Baylis Studio, Sadler’s Wells INDEPENDENT OPERA RECOGNISED AT THE 2016 INTERNATIONAL OPERA AWARDS Philanthropists of the Year – Bill & Judy Bollinger Polly Graham is today announced as winner of Independent Opera’s (IO) 2016 Director Fellowship. Nominated for the Fellowship by Michael McCarthy (Artistic Director, Music Theatre Wales) and Isabel Murphy (Director of Artistic Administration, Welsh National Opera), Polly will stage the UK première of Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s Simplicius Simplicissimus, in a new English translation by David Pountney, who also translated IO’s 2015 production of Biedermann and the Arsonists. In addition to financial support, Polly will receive mentoring from Pountney and Stephen Medcalf, both panellists during the selection process. Independent Opera will present Simplicius Simplicissimus at the Lilian Baylis Studio at Sadler’s Wells on 11, 15, 17 and 19 November 2016. A graduate of Trinity College, Dublin and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, Polly was Welsh National Opera’s first Genesis Assistant Director (2012-2014) and her recent work there has included directing Iain Bell’s A Christmas Carol and working as Associate Director on his new work, In Parenthesis. On winning the IO 2016 Director Fellowship, she said: “Independent Opera has given me wonderful encouragement from the start of the Fellowship; in supporting the production of Hartmann’s superb but little known opera, Simplicius Simplicissimus, they are allowing me to step into new territory and make work that I really believe in.” Independent Opera at Sadler’s Wells was founded in 2005 to serve as a platform for outstanding young artists in every discipline of opera. -

Opera & Ballet 2017

12mm spine THE MUSIC SALES GROUP A CATALOGUE OF WORKS FOR THE STAGE ALPHONSE LEDUC ASSOCIATED MUSIC PUBLISHERS BOSWORTH CHESTER MUSIC OPERA / MUSICSALES BALLET OPERA/BALLET EDITION WILHELM HANSEN NOVELLO & COMPANY G.SCHIRMER UNIÓN MUSICAL EDICIONES NEW CAT08195 PUBLISHED BY THE MUSIC SALES GROUP EDITION CAT08195 Opera/Ballet Cover.indd All Pages 13/04/2017 11:01 MUSICSALES CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 1 1 12/04/2017 13:09 Hans Abrahamsen Mark Adamo John Adams John Luther Adams Louise Alenius Boserup George Antheil Craig Armstrong Malcolm Arnold Matthew Aucoin Samuel Barber Jeff Beal Iain Bell Richard Rodney Bennett Lennox Berkeley Arthur Bliss Ernest Bloch Anders Brødsgaard Peter Bruun Geoffrey Burgon Britta Byström Benet Casablancas Elliott Carter Daniel Catán Carlos Chávez Stewart Copeland John Corigliano Henry Cowell MUSICSALES Richard Danielpour Donnacha Dennehy Bryce Dessner Avner Dorman Søren Nils Eichberg Ludovico Einaudi Brian Elias Duke Ellington Manuel de Falla Gabriela Lena Frank Philip Glass Michael Gordon Henryk Mikolaj Górecki Morton Gould José Luis Greco Jorge Grundman Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Albert Guinovart Haflidi Hallgrímsson John Harbison Henrik Hellstenius Hans Werner Henze Juliana Hodkinson Bo Holten Arthur Honegger Karel Husa Jacques Ibert Angel Illarramendi Aaron Jay Kernis CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 2 12/04/2017 13:09 2 Leon Kirchner Anders Koppel Ezra Laderman David Lang Rued Langgaard Peter Lieberson Bent Lorentzen Witold Lutosławski Missy Mazzoli Niels Marthinsen Peter Maxwell Davies John McCabe Gian Carlo Menotti Olivier Messiaen Darius Milhaud Nico Muhly Thea Musgrave Carl Nielsen Arne Nordheim Per Nørgård Michael Nyman Tarik O’Regan Andy Pape Ramon Paus Anthony Payne Jocelyn Pook Francis Poulenc OPERA/BALLET André Previn Karl Aage Rasmussen Sunleif Rasmussen Robin Rimbaud (Scanner) Robert X. -

30 Key Influencers in the Performing Arts on the Cover 1

december 2013 MOVERS & SHAKERS 30 Key Influencers in the Performing Arts On The Cover 1. Deborah rutter President Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association 2. timothy o’Leary 1 General Director Opera Theater of Saint Louis 3. matías tarnopoLsky Director Cal Performances 2 3 4 5 4. stéphane Lissner 6 7 General Manager and Artistic Director Teatro alla Scala, Milan 10 11 5. Darren henLey Managing Director Classic FM 6. roger Wright 8 9 Controller BBC Radio 3 Director BBC Proms 7. Limor tomer 15 1 7 General Manager, Concerts and Lectures Metropolitan Museum of Art 12 13 8. marc scorca President and CEO 14 11 6 6 1 8 Opera America 9. brent assink Executive Director San Franciso Symphony 10. Joseph poLisi President and Trustee The Juilliard School 1 9 20 21 22 23 11. roLanD geyer Intendant Theater an der Wien 18. DaViD gockLey 12. heLga rabL-stabLer General Director President San Francisco Opera Salzburg Festival 19. John giLhooLy 13. Janis susskinD Director, Wigmore Hall 24 25 26 27 2829 30 Managing Director Chairman, Royal Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Philharmonic Society 14. Jenny biLfieLD 20. Jonathan frienD 24. Deborah borDa, President and CEO, Los Angeles Philharmonic President and CEO Artistic Administrator Washington Performing Arts Society Metropolitan Opera 25. anthony freuD, General Director, Lyric Opera of Chicago 15. peter taub 21. kristin Lancino 26. peter geLb, General Manager, Metropolitan Opera Director of Performance Programs Executive Director Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago IMG Artists 27. cLiVe giLLinson, Executive and Artistic Director, Carnegie Hall 16. mark VoLpe 22. DaViD foster 28. kLaus heymann, CEO, Naxos Managing Director President and CEO Boston Symphony Orchestra Opus 3 Artists 29. -

Polly Graham Appointed Artistic Director of Longborough Festival Opera

POLLY GRAHAM APPOINTED ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF LONGBOROUGH FESTIVAL OPERA Acclaimed opera director Polly Graham is to become Artistic Director of Longborough Festival Opera. The 33-year-old daughter of Martin and Lizzie Graham says: “As a family we are so proud of Longborough and have long talked about its future. But it is only recently that I have felt ready to take on the challenge of leading it forward.” The Longborough theatre was built on a dream in the garden of maverick impresario Martin Graham’s family home, and opened in 1997. From the beginning Lizzie Graham has been running the shows, and in 2014 appointed Jennifer Smith as General Image cr Jorge Lizalde Manager. Looking to the future, Martin and Lizzie will continue to be deeply involved in the festival, and it is with their blessing that Polly will steer it in a new direction. Lizzie Graham says: “We are delighted that Polly will be continuing the Longborough legacy. It seems the perfect way to build on what has been achieved here.” Polly will take up her new role with immediate effect, combining it with her independent directing career. She aims to preserve the special atmosphere created by her parents. “Longborough has established itself as a mecca for Wagnerians, led by the esteemed conductor Anthony Negus. I intend to build on the spirit of the festival, which has been willfully daring and ambitious, by expanding repertoire and commissioning new work. My aim is to share great opera with as many people as possible.” - ends - For further information: [email protected] | [email protected] | Web: https://lfo.org.uk/ Image links: Longborough imagery: https://lfo.org.uk/index.php/actions/supercoolTools/downloadFile?id=3253 Polly Graham: http://www.caroline-phillips.co.uk/_images/artists/hi-res/polly-graham-2.jpg Longborough Festival Opera New Banks Fee, Longborough, Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire, GL56 0QF T 01451 830292 E [email protected] lfo.org.uk Company No. -

WNO Annual Review 15

2015/2016 Annual Review Making opera matter, NOW Great opera, NOW Reaching further, NOW The future, NOW Together, NOW Great value, NOW Making opera matter, NOW Welsh National Opera believes that opera matters now. It can Last year we provided more opportunities than ever for children entertain, engage and bring people together. Over the course and members of the community across our touring regions of the 2015/2016 Season we showed just what opera can do. to take part in WNO projects and workshops. Our activities included innovative education projects and community choirs. We are committed to ensuring that opera remains a thriving, living, breathing art form. For us, opera doesn’t simply offer WNO works hard to make the most of every pound of public great nights out but can also stimulate debate and ask essential investment. Throughout 2015/2016 we supplemented that questions about the world in which we live. Our themed season income in many different ways including ticket sales, fundraising programming and two new world premières were proof of and hiring opera productions to other companies. our artistic ambition. Critical and audience acclaim for our performances recognised the Company’s exceptionally high No project in 2015/2016 better demonstrated what WNO and artistic standards. opera can do than In Parenthesis: We believe that opera can have value for everyone and make a real difference to people’s lives. In 2015/2016 we reached more people in more ways through our performances, our work with young people and in local communities, digital activity and social media reach. -

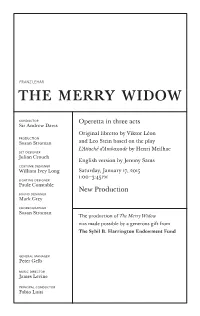

The Merry Widow

FRANZ LEHÁR the merry widow conductor Operetta in three acts Sir Andrew Davis Original libretto by Viktor Léon production Susan Stroman and Leo Stein based on the play L’Attaché d’Ambassade by Henri Meilhac set designer Julian Crouch English version by Jeremy Sams costume designer William Ivey Long Saturday, January 17, 2015 1:00–3:45 PM lighting designer Paule Constable New Production sound designer Mark Grey choreographer Susan Stroman The production of The Merry Widow was made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine principal conductor Fabio Luisi The 32nd Metropolitan Opera performance of FRANZ LEHÁR’S the merry widow This performance is being broadcast live over The conductor Sir Andrew Davis Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera in order of vocal appearance International Radio vicomte cascada bogdanovitch Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, Jeff Mattsey Mark Schowalter America’s luxury njegus ® baron mirko zeta homebuilder , with Sir Thomas Allen Carson Elrod generous long-term support from valencienne hanna gl awari The Annenberg Kelli O’Hara Renée Fleming Foundation, The Neubauer Family sylviane count danilo danilovitch Foundation, the Emalie Savoy* Nathan Gunn* Vincent A. Stabile olga woman Endowment for Wallis Giunta* Andrea Coleman Broadcast Media, and contributions pr askowia maître d’ from listeners Margaret Lattimore* Jason Simon worldwide. camille de rosillon griset tes There is no Alek Shrader LOLO Synthia Link Toll Brothers– DODO Alison Mixon r aoul de st. brioche Metropolitan Opera JOUJOU Emily Pynenburg Alexander Lewis* Quiz in List Hall today. FROUFROU Leah Hofmann CLOCLO kromow Jenny Laroche This performance is Daniel Mobbs MARGOT Catherine Hamilton also being broadcast live on Metropolitan pritschitsch Opera Radio on Gary Simpson SiriusXM channel 74. -

Fidelio Beethoven Welcome

FIDELIO BEETHOVEN WELCOME Welcome to Opera North’s new concert staging with and for our communities in the north of England of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. This performance and beyond; hence the present live streamed is being live streamed just a few days before the performance. probable date of Beethoven’s birth 250 years ago this month. It is therefore our contribution to the Whilst we have all felt keenly the loss of live Beethoven 250 celebrations, but it also feels performance over the past several months, the a particularly appropriate work to be performing effect on the livelihoods of freelance musicians at the end of what has been an extraordinarily and theatre workers has been nothing short of difficult year for everyone. devastating, and the hard times will continue well into 2021. We have regretfully taken the decision In this opera, Beethoven dramatises the principles to postpone our concert staging of Parsifal next to which he was committed in the public sphere – spring; any requirement for social distancing would liberty, justice, fraternity – through a story that was make it impossible for us to mount a work of this of deep emotional importance to him. In the years scale. Some members of the present cast of Fidelio since it was first performed, Fidelio has often been were due to appear in Parsifal, but we hope to charged with new significance in times of crisis; and feature them in a replacement – Wagner-related – this year, the image of an individual held in a state programme to be announced in the new year. -

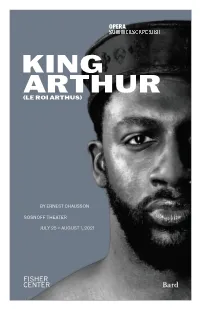

Opera King Arthur 7-21.Indd

OPERA SUMMERSCAPE 2021 King Arthur (LE ROI ARTHUS) BY ERNEST CHAUSSON SOSNOFF THEATER JULY 25 – AUGUST 1, 2021 Fisher Center The Fisher Center develops, produces, and presents performing arts across disciplines through new productions and context-rich programs that challenge and inspire. As a premier professional performing arts center and a hub for research and education, the Fisher Center supports artists, students, and audiences in the development and examination of artistic ideas, offering perspec- tives from the past and present, as well as visions of the future. The Fisher Center demonstrates Bard’s commitment to the performing arts as a cultural and educational necessity. Home is the Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, designed by Frank Gehry and located on the campus of Bard College in New York’s Hudson Valley. The Fisher Center offers outstanding programs to many com- munities, including the students and faculty of Bard College, and audiences in the Hudson Valley, New York City, across the country, and around the world. The Center presents more than 200 world-class events and welcomes 50,000 visitors each year. The Fisher Center supports artists at all stages of their careers and employs more than 300 profes- sional artists annually. The Fisher Center is a powerful catalyst of art-making regionally, nationally, and worldwide. Every year it produces eight to 10 major new works in various disciplines. Over the past five years, its commissioned productions have been seen in more than 100 communities around the world. During the 2018–19 season, six Fisher Center productions toured nationally and internationally.