Censoring Queen Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victoria: the Irg L Who Would Become Queen Lindsay R

Volume 18 Article 7 May 2019 Victoria: The irG l Who Would Become Queen Lindsay R. Richwine Gettysburg College Class of 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Richwine, Lindsay R. (2019) "Victoria: The irlG Who Would Become Queen," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 18 , Article 7. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol18/iss1/7 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Victoria: The irG l Who Would Become Queen Abstract This research reviews the early life of Queen Victoria and through analysis of her sequestered childhood and lack of parental figures explains her reliance later in life on mentors and advisors. Additionally, the research reviews previous biographical portrayals of the Queen and refutes the claim that she was merely a receptacle for the ideas of the men around her while still acknowledging and explaining her dependence on these advisors. Keywords Queen Victoria, England, British History, Monarchy, Early Life, Women's History This article is available in The Gettysburg Historical Journal: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol18/iss1/7 Victoria: The Girl Who Would Become Queen By Lindsay Richwine “I am very young and perhaps in many, though not in all things, inexperienced, but I am sure that very few have more real good-will and more real desire to do what is fit and right than I have.”1 –Queen Victoria, 1837 Queen Victoria was arguably the most influential person of the 19th century. -

Victorian England Week Twenty One the Victorian Circle: Family, Friends Wed April 3, 2019 Institute for the Study of Western Civilization

Victorian England Week Twenty One The Victorian Circle: Family, Friends Wed April 3, 2019 Institute for the Study of Western Civilization ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Victoria and Her Ministers ThursdayApril 4, 2019 THE CHILDREN (9 born 1840-1857) ThursdayApril 4, 2019 ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Victoria Albert Edward (Bertie, King Ed VII) Alice Alfred Helena Louise Arthur Leopold Beatrice ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Queen Victoria with Princess Victoria, her first-born child. (1840-1901) ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Albert and Vicky ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Princess Victoria 1840-1901 ThursdayApril 4, 2019 1858 Marriage of eldest daughter Princess Victoria (Vicky) to “Fritz”, King Fred III of Prussia Albert and Victoria adored him. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Princess Victoria (Queen of Prussia) Frederick III and two of their children. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Queen Victoria with her first grandchild (Jan, 1858) Wilhelm, future Kaiser Wilhelm II ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Queen Victoria and Vicky, the longest, most continuous, most intense relationship of all her children. 5,000 letters, 60 years. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Little baby Bertie with sister Vickie ThursdayApril 4, 2019 Albert, Edward (Bertie) Prince of Wales age 5 in 1846 1841-1910) ThursdayApril 4, 2019 1860 18 year old Prince of Wales goes to Canada and the USA ThursdayApril 4, 2019 1860 Prince of Wales touring the USA and Canada (Niagara Falls) immensely popular, able to laugh and engage the crowds. They loved him. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 His closest friend in the whole world was his sister Alice to whom he could confide anything. ThursdayApril 4, 2019 1861 Bertie’s Fall: An actress, Nellie Clifden 6 Sept Curragh N. -

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in the Young Victoria (2009)

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in The Young Victoria (2009) Julia Kinzler (Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany) Abstract This article explores the ambivalent re-imagination of Queen Victoria in Jean-Marc Vallée’s The Young Victoria (2009). Due to the almost obsessive current interest in Victorian sexuality and gender roles that still seem to frame contemporary debates, this article interrogates the ambiguous depiction of gender relations in this most recent portrayal of Victoria, especially as constructed through the visual imagery of actual artworks incorporated into the film. In its self-conscious (mis)representation of Victorian (royal) history, this essay argues, The Young Victoria addresses the problems and implications of discussing the film as a royal biopic within the generic conventions of heritage cinema. Keywords: biopic, film, gender, genre, iconography, neo-Victorianism, Queen Victoria, royalty, Jean-Marc Vallée. ***** In her influential monograph Victoriana, Cora Kaplan describes the huge popularity of neo-Victorian texts and the “fascination with things Victorian” as a “British postwar vogue which shows no signs of exhaustion” (Kaplan 2007: 2). Yet, from this “rich afterlife of Victorianism” cinematic representations of the eponymous monarch are strangely absent (Johnston and Waters 2008: 8). The recovery of Queen Victoria on film in John Madden’s visualisation of the delicate John-Brown-episode in the Queen’s later life in Mrs Brown (1997) coincided with the academic revival of interest in the monarch reflected by Margaret Homans and Adrienne Munich in Remaking Queen Victoria (1997). Academia and the film industry brought the Queen back to “the centre of Victorian cultures around the globe”, where Homans and Munich believe “she always was” (Homans and Munich 1997: 1). -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of -

Job Description

The Royal Household JOB DESCRIPTION JOB TITLE: Administrator, Picture Conservation Studio DEPARTMENT: Royal Collection Trust SECTION/BRANCH: Paintings Conservation LOCATION: Windsor Castle REPORTING TO: Registrar (Pictures) and Conservation Studio Co-ordinator Job Context Royal Collection Trust is a department of the Royal Household and the only one that undertakes its activities without recourse to public funds. It incorporates a charity regulated by the Charity Commission and the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, The Royal Collection Trust, and its subsidiary trading company, Royal Collection Enterprises Limited. Royal Collection Trust is charged with the care and preservation of the Royal Collection and its presentation to the public. The Royal Collection is one of the largest and most important art collections in the world. It comprises almost all aspects of the fine and decorative arts, runs to more than a million objects and is spread among some thirteen royal residences and former residences across the UK. At The Queen’s Galleries in London and Edinburgh, aspects of the Collection are displayed in a programme of temporary exhibitions. Many works from the Collection are on long-term loan to institutions throughout the UK and short-term loans are regularly made to exhibitions around the world as part of a commitment to broaden public access and to show parts of the Collection in new contexts. The works of art in the Royal Collection are held by The Queen in trust for her successors and the nation. Royal Collection Trust is responsible for the management and financial administration of the public opening of Buckingham Palace (including The Queen’s Gallery, the Royal Mews and Clarence House), Windsor Castle (including Frogmore House) and the Palace of Holyroodhouse (including The Queen’s Gallery). -

Outliers – Stories from the Edge of History Faithfully Yours, Louise Lezhen

Outliers – Stories from the edge of history is produced for audio and specifically designed to be heard. Transcripts are created using human transcription as well as speech recognition software, which means there may be some errors. Outliers – Stories from the edge of history Season Two, Episode Five Faithfully yours, Louise Lezhen By Lettie Precious Louise Lezhen: Clink clank, clink clank, clearing throats, halting conversations. Silverware making more chatter with the dinner ware. Clink clank, clickity clank. Throats clearing, halting conversations full of ‘So’ clink ‘Well’ clank Mmmhh clink. Heavy sighs, polite questions, polite answers, stretches of silence, quiet. Quiet where pin drops can be heard. It is in those times, I say nothing, my voice, no longer holding the power it once had, but missing it greatly. There’s a new chill in the air, a new cold snaking its way up and down the corridors of Kensington Palace, making its presence felt for a while now. Things have changed…different now, even the birds are nervous in their songs. The sun peeks through the windows with great caution, even I, once governess to the princess walk the floors of this Palace differently, cautiously…. After years and years, holding Victoria’s hand, her little hand fitting so perfectly in mine; her little feet following so gracefully behind my footprints. Oh, the privilege I had, a power that once roared in me, no one could tell me anything. She was mine to keep, to teach, to protect…. (sigh) But things are different now, even the walls seem to protest, drawing closer together each day, encouraging the ceilings to drop too, a force that threatens to crush me at any given moment. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

FACT SHEET Frogmore House Frogmore House

FACT SHEET Frogmore House Frogmore House is a private, unoccupied residence set in the grounds of the Home Park of Windsor Castle. It is frequently used by the royal family for entertaining. It was recently used as the reception venue for the wedding of The Queen’s eldest grandson, Peter Phillips, to Autumn Kelly, in May 2008. How history shaped Frogmore The estate in which Frogmore House now lies first came into royal ownership in the 16th century. The original Frogmore House was built between 1680 and 1684 for tenants Anne Aldworth and her husband Thomas May, almost certainly to the designs of his uncle, Hugh May who was Charles II’s architect at Windsor. From 1709 to 1738 Frogmore House was leased by the Duke of NorthumberlandNorthumberland, son of Charles II by the Duchess of Cleveland. The House then had a succession of occupants, including Edward Walpole, second son of the Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole. In 1792 George III (r. 1760-1820) bought Frogmore House for his wife Queen CharlotteCharlotte, who used it for herself and her unmarried daughters as a country retreat. Although the house had been continuously occupied and was generally in good condition, a number of alterations were required to make it fit for the use of the royal family, and architect James Wyatt was appointed to the task. By May 1795, Wyatt had extended the second floor and added single- storey pavilions to the north and south of the garden front, linked by an open colonnade and in 1804 he enlarged the wings by adding a tall bow room and a low room beyond, to make a dining room and library at the south end and matching rooms at the north. -

The Young Victoria Production Notes

THE YOUNG VICTORIA PRODUCTION NOTES GK Films Presents THE YOUNG VICTORIA Emily Blunt Rupert Friend Paul Bettany Miranda Richardson Jim Broadbent Thomas Kretschmann Mark Strong Jesper Christensen Harriet Walter Directed by Jean-Marc Vallée Screenplay By Julian Fellowes Produced by Graham King Martin Scorsese Tim Headington Sarah Ferguson, The Duchess of York 2 SHORT SYNOPSIS The Young Victoria chronicles Queen Victoria's ascension to the throne, focusing on the early turbulent years of her reign and her legendary romance and marriage to Prince Albert. SYNOPSIS 1837. VICTORIA (17) (Emily Blunt) is the object of a royal power struggle. Her uncle, KING WILLIAM (Jim Broadbent), is dying and Victoria is in line for the throne. Everyone is vying to win her favor. However Victoria is kept from the court by her overbearing mother, THE DUCHESS OF KENT (Miranda Richardson), and her ambitious advisor, CONROY (Mark Strong). Victoria hates them both. Her only friend is her doting governess, LEHZEN (Jeanette Hain), who is seemingly as untrustworthy as the rest. Victoria’s handsome cousin, ALBERT (Rupert Friend) is invited to visit by her mother. He's also the nephew of her Uncle, KING LEOPOLD OF BELGIUM (Thomas Kretschmann). It's obvious that Albert has been coached to win her hand. At first she's annoyed as she has no intention of being married. She never wants to be controlled again. However Albert is also tired of being manipulated by his relatives. Victoria and Albert talk openly and sincerely and become friends. When he returns home she grants him permission to write to her. -

Introduction

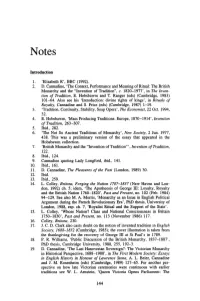

Notes Introduction 1. 'Elizabeth R·. BBC (1992). 2. D. Cannadine. 'The Context. Perfonnance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the "Invention of Tradition". c. 1820-1977'. in The Inven tion of Tradition. E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger (eds) (Cambridge. 1983) 101-64. Also see his 'Introduction: divine rights of kings'. in Rituals of Royalty. Cannadine and S. Price (eds) (Cambridge. 1987) 1-19. 3. 'Tradition. Continuity. Stability. Soap Opera'. The Economist. 22 Oct. 1994. 32. 4. E. Hobsbawm. 'Mass Producing Traditions: Europe. 1870-1914'. Invention of Tradition. 263-307. 5. Ibid .• 282. 6. 'The Not So Ancient Traditions of Monarchy'. New Society. 2 Jun. 1977. 438. This was a preliminary version of the essay that appeared in the Hobsbawm collection. 7. 'British Monarchy and the "Invention of Tradition"'. Invention of Tradition. 122. 8. Ibid .• 124. 9. Cannadine quoting Lady Longford. ibid .• 141. 10. Ibid .• 161. 11. D. Cannadine. The Pleasures of the Past (London. 1989) 30. 12. Ibid. 13. Ibid .• 259. 14. L. Colley. Britons, Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (New Haven and Lon don. 1992) ch. 5; idem. 'The Apotheosis of George ill: Loyalty. Royalty and the British Nation 1760-1820'. Past and Present. no. 102 (Feb. 1984) 94-129. See also M. A. Morris. 'Monarchy as an Issue in English Political Argument during the French Revolutionary Era'. PhD thesis. University of London. 1988. esp. ch. 7. 'Royalist Ritual and the Support of the State'. 15. L. Colley. 'Whose Nation? Class and National Consciousness in Britain 1750-1830'. Past and Present. no. 113 (November 1986) 117. 16. -

King George VI Wikipedia Page

George VI of the United Kingdom - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 10/6/11 10:20 PM George VI of the United Kingdom From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from King George VI) George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom George VI and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death. He was the last Emperor of India, and the first Head of the Commonwealth. As the second son of King George V, he was not expected to inherit the throne and spent his early life in the shadow of his elder brother, Edward. He served in the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force during World War I, and after the war took on the usual round of public engagements. He married Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon in 1923, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret. George's elder brother ascended the throne as Edward VIII on the death of their father in 1936. However, less than a year later Edward revealed his desire to marry the divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson. British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin advised Edward that for political and Formal portrait, c. 1940–46 religious reasons he could not marry Mrs Simpson and remain king. Edward abdicated in order to marry, and George King of the United Kingdom and the British ascended the throne as the third monarch of the House of Dominions (more...) Windsor. Reign 11 December 1936 – 6 February On the day of his accession, the parliament of the Irish Free 1952 State removed the monarch from its constitution.