Kant on the Transcendental Deduction of Space and Time: an Essay on the Philosophical Resources of the Transcendental Aesthetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Department Is Changing with the Times

MUShare The Carbon Campus Newspaper Collection 9-13-1999 The Carbon (September 13, 1999) Marian University - Indianapolis Follow this and additional works at: https://mushare.marian.edu/crbn Recommended Citation Marian University - Indianapolis, "The Carbon (September 13, 1999)" (1999). The Carbon. 116. https://mushare.marian.edu/crbn/116 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Campus Newspaper Collection at MUShare. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Carbon by an authorized administrator of MUShare. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 4 ISSUE 2 A MARIAN COLLEGE STUDENT PUBLICATION SEPTEMBER 13, 1999 Education Department Is We're Changing with the Times s By Kate Rave by Wendy Nine New faces, they are abso In light of the new state pleted prior to student teaching. will notify students if this option lutely everywhere. Maybe you guide lines for licensing in edu- Students will also notice a will continue in the future. are a freshman and every face cation, Marian's Education De change in the curriculum. There The department is offering but your roommate is strange. partment has made some is a new protocol for reflective service learning opportunites Maybe you're a senior, and there changes to their handbook. journaling being used in Edu throughtout the year. are just some faces you don't All students must be Project Enhance needs recognize. Maybe you are a staff formally admitted to the de students to work with member, and there are unfamil partment before they can middle school children iar faces at your staff meeting. -

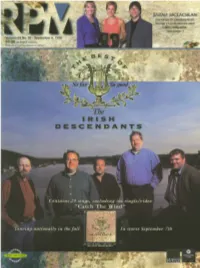

"Catch the Wind"

DESCENDANTS IRISH THE OF BEST THE GOOD SO FAR SO fall the in nationally Touring Wind" The "Catch single/video the including songs, .19 Contains , " ". ! '"'. 08141 No. Registration Mail Publication GST) .20 plus ($2.80 $3.00 1999 6, September - 20 No. 69 Volume 3 paae See - GiElesValtquetie.., and re Mo Socan'slinda from plaques 01 iecehies -SARAHCLACHL1 a. 100 HIT TRACKS New Bowie release a David Bowie, one of music's most innc will take the recording industry anothe & where to find them in September, when his new album, h( available for download via the interne Record Distributor Codes: Canada's Only National 100 Hit Tracks Survey BMG - N EMI - F Universal - J Virgin Records America announce Polygram - Q Sony - H Warner - P indicates biggest mover in conjunction with fifty leading music album will be available on the 'net S TW LW WOSEPTEMBER 6, 1999 Bruce Barker name 1 1 13 IF YOU HAD MY LOVE 35 39 6 SMILE 68 67 40 BABY ONE MORE TIME Jennifer Lopez - On The 6 Vitamin C - Self Titled Britney Spears - Baby One More Time Work 69351 (pro single) - P Elektra 62406 (comp 405) - P Jive 41651 (pro single) -N Bruce "The Barkman" Barker has been 1M 7 13 GENIE IN A BOTTLE 36 25 21 SOMETIMES 69 64 26 ANYTHING BUT DOWN director of Toronto's CFRB. He succee Christina Aguilera - Self Titled Britney Spears - ... Baby One More Time Sheryl Crow - The Globe Sessions RCA (CD Track) - N Jive 41651 (CD Track) - N ARM 540959 (CD Track) - J Bill Stephenson, a sports broadcast let 3 2 14 ALL STAR 37 29 20 CLOUD #9 70 63 20 UNTIL YOU LOVED ME covered forty years of sports, most ofi Smash Mouth - Astro Lounge Bryan Adams - On A Day Like Today eA The Moffatts - Never Been Kissed O.S.T. -

Aimee Mann's Idea of Eccentric Covers the Waterfront

Sunday, June 15, 2008 N N H 3 ArtScene From Carnegie to ‘Candide’ Light Opera role tempts Brian Cheney back to a Tulsa stage BY JAMES D. WATTS JR. World Scene Writer Candide For Brian Cheney, having the title role WHEN: in Light Opera Oklahoma’s production of 8 p.m. Saturday “Candide” is a slightly bittersweet experi- ence. WHERE: It’s a role that Cheney has always wanted Williams Theater, Tulsa Performing Arts Center, Second to do, and the main reason why the tenor Street and Cincinnati Avenue. has returned for his second season with LOOK. TICKETS: “I have a wife and two daughters, ages $25-$29, 596-7111 or www.tulsaworld.com/mytix 7 and 5, and working with this company means I’m going to be away from them for two months,” Cheney said. “And it’s always LOOK will be using the version created tough to be away for so long a time, so in 1973, the so-called “Chelsea” version, there’s got to be a good reason to do it. named for the theater where it debuted. “And that’s what ‘Candide’ is for me,” he The book is by Wheeler, who streamlined said. “Eric (Gibson, LOOK artistic director) the show into a single act that more closely and I started talking about this show before follows Voltaire’s original story. we finished last season’s productions. When “One of the great things about this ver- Eric said he was serious about doing ‘Can- sion is that it gives the audience a clearer dide,’ I said I was in, and I’d do whatever focus,” Cheney said. -

Katy Perry's Pinup Perfect

Culture MONDAY, AUGUST 9, 2010 an you read sheet music?” asks Katy a rocket and you’re hanging on for dear life and Perry as we climb the stairs of a photo you’re like, ‘Gooooooo!’ The second record I’m studio on Broadway. more buckled in because, God, how many times do “A little,” I say. you see people slump on their sophomore record? She stops and holds out the edges Katy Perry’s Nine out of 10. But I’m still working, like, 13-hour “Cof her dress, patterned with a series of ascending days, five, six days a week and singing on top of it. quavers and semiquavers. “Then what song am I?” she And knowing that there’s someone right behind me, asks, twirling. ready to go, ready to push me down the stairs, just “Three Blind Mice?” like in Showgirls.” “The Girl From Ipanema,” she says, before The middle child of three, her parents were breaking into song. “I feel like I’m squeezed into a pinup both born-again Pentecostal ministers in southern giant condom in this dress,” she adds. California — Christian camp, Christian friends, no Retro pop reference, modern twist, smutty MTV, no radio — but press stories of a parental punchline: I’m with the right Katy Perry, then. It’s a rift over Perry’s lyrics ignore the “born again” bit. sweltering day in Manhattan — temperatures are in Before they came to their faith, her parents were the 30s — but Perry, who arrived from Los Angeles perfect 60s scenesters, her mother briefly dating Jimi a few days ago, isn’t complaining. -

MICHAEL JACKSON 101 Greatest SONGS

MICHAEL JACKSON 101 101 GrEAtESt Songs MICHAEL JACKSON 101 101 GrEAtESt Songs &E Andy Healy MICHAEL JACKSON 101 101 GrEAtESt Songs . Andy Healy 2013 Dedicated first and foremost to Michael Jackson and the Jackson family for a lifetime of music. Under the Creative Commons licence you are free to share, copy, distribute and transmit this work with the proviso that the work not be altered in any way, shape or form and that all And to all the musicians, writers, arrangers, engineers and producers written works are credited to Andy Healy as author. This Creative Commons licence does not who shared their talents and brought these musical masterpieces into being. extend to the copyrights held by the photographers and their respective works. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. This book is also dedicated to the fans the world over - new, old, and yet to be - who by exploring the richness in the art will ensure Michael’s musical legacy I do not claim any ownership of the photographs featured and all rights reside with the original and influence continues on. copyright holders. Images are used under the Fair Use Act and do not intend to infringe on the copyright holders. Finally thanks to Trish who kept the encouragement coming and to all who welcomed this book with open arms. This is a book by a fan for the fans. &E any great books have been written about Michael’s music and artistry. This Mcollection of 101 Greatest Songs is by no means absolute, nor is in intended to be. -

Sweet Georgia Brown Karaoke Song Book

Sweet Georgia Brown Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 112 Afroman Peaches And Cream SGB65-18 Because I Got High SGB65-01 3 Doors Down Al Jarreau Kryptonite SGB47-14 After All SGB51-02 Kryptonite SGBSP01-3-09 Al Martino 38 Special Spanish Eyes SGB59-11 Hold On Loosely SGB1016-08 Alabama Hold On Loosely SGB16-08 God Must Have Spent A Little More Time On You SGB17-01 98 Degrees Mountain Music SGB1003-18 Hardest Thing, The SGB18-06 Alan Jackson Hardest Thing, The SGBSP01-2-09 Gone Crazy SGB17-10 I Do (Cherish You) SGB18-15 Pop A Top SGB29-04 I Do (Cherish You) SGBSP01-2-12 Alanis Morissette A3 Forgiven SGB08-15 Woke Up This Morning SGB38-19 Forgiven SGB1012-15 Aaron Neville So Pure SGB30-14 Everybody Plays The Fool SGB57-09 Thank U SGB08-07 ABBA Thank U SGB1012-07 Dancing Queen SGB58-01 Uninvited SGB06-13 Dancing Queen SGBFSP-3-15 Unsent SGB06-09 Waterloo SGB1019-14 You Learn SGB21-09 Waterloo SGB32-14 You Learn SGBFSP-2-02 Waterloo SGB58-05 You Oughta Know SGB21-03 Waterloo SGBFSP-2-08 You Oughta Know SGBFSP-1-16 AC-DC Albert King Back In Black SGB1014-11 Call My Job SGB27-10 Back In Black SGB14-11 Good Time Charlie SGB27-03 Hell's Bells SGB1014-01 Alice Cooper Hell's Bells SGB14-01 Ballad Of Dwight Fry SGB09-14 Hell's Bells SGBCRP-1-08 Be My Lover SGB09-11 Highway To Hell SGB48-14 Billion Dollar Babies SGB09-08 Stiff Upper Lip SGB48-02 Dead Babies SGB09-15 Stiff Upper Lip SGB63-11 Dead Babies SGBCRP-1-07 Whole Lotta Rosie SGB48-06 Desperado SGB09-06 Adam Sandler Feed My Frankenstein SGB09-09 Piece -

St Kateri Catholic Church – Dearborn, Michigan

16101 Rotunda Dr. Dearborn, MI 48120 St. Kateri Phone 313-336-3227 Fax 313-441-6769 Catholic Church https://stkateridearborn.org AUGUST 8, 2021 NINETEENTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME PASTOR Rev. Terrence D. Kerner WEEKEND ASSOCIATE Rev. Gary Morelli DEACON THE OF LIFE Rev. Mr. Thomas Leonard 7 FAITH DIRECTOR: Grace Lakatos Decide to have a good day. “This is the day the ORGANIST: Kevin Jakubowicƶ Wake UP Lord has made, let us rejoice and be glad in it.” OFFICE STAFF Mary Masley & Ellie Sajewski The best way to dress up is to put on a smile E-MAIL Dress UP on your face and in your heart. Remember, [email protected] man usually looks at outward appearance, but OFFICE HOURS the Lord looks at the heart. Monday thru Friday: 9:00 AM - Noon and 1:00 - 4:30 PM Say nice things and learn to listen. God gave WEEKEND MASS SCHEDULE Shut UP us two ears and one mouth. He must have Saturday: 4:00 PM Sunday: 9:00 & 11:00 AM meant for us to do twice as much listening as WEEKDAY MASS SCHEDULE talking. Tuesday: 6:40 PM Wednesday—Friday: 9:00 AM Look at your cherished ideals and opportuni- Stand UP CONFESSIONS ties to do good. If you don’t stand up for some- Saturday: 3:00 PM thing you will fall for anything. ADORATION Tuesday: 4:00–6:30 PM Reach for the Lord. Remember, you can do Look UP everything through Christ who strengthens PERPETUAL HELP DEVOTIONS Tuesday at 6:30 PM and you. -

Dialogue: the Sixth and Seventh Mansions (Part 2) with James Finley Yvette Trujillo: You’Re Listening to a Podcast by the Center for Action and Contemplation

Dialogue: The Sixth and Seventh Mansions (Part 2) with James Finley Yvette Trujillo: You’re listening to a podcast by the Center for Action and Contemplation. To learn more, visit cac.org. Jim Finley: Greetings. I’m Jim Finley. Kirsten Oates: And I’m Kirsten Oates. Welcome to Turning to the Mystics. [music; bell] Welcome, everyone. I’m grieving and celebrating as we come to the end of our time with the 16th-century Christian mystic, Teresa of Ávila, and her beautiful book, the Interior Castle. Today will be my final dialogue with Jim looking at Mansions six and seven and getting his help to unpack some of the deep and mystical concepts that Teresa offers us in that book. Next week, we’ll be looking at questions that have come in from you all. So, thank you so much for sending those in. We’re excited to hear your thoughts and questions next week, but now let’s get started with Jim on the sixth and seventh Mansions. Okay. Welcome, Jim. We’re back again, take two or part two, because I’ve just found these sixth and seventh Mansions so deep, and there are so many new concepts within them that it was hard to get through them both in one session last week. So, we’re back again in a dialogue about Mansions six and seven. So, my first question is why do you think the sixth Mansion is so long in the book? Jim Finley: Yes. Well, it’s by far the longest— Kirsten Oates: Eleven chapters, right? It’s by far the longest Jim Finley: I think because, intuitively, it seems to me, the reason is, is that let’s say from the fourth Mansion on, there are the beginnings of these, what she calls special favors or mystical states of the experience of God radiating out from the seventh, innermost Mansion. -

New Order # 100169878

Go ahead and belt one out! Please use the blank paper to write your NAME, SONG NAME, SONG NUMBER & DISC NUMBER, and bring it to the Karaoke Emcee. DISC# SONG# Artist Song Name 65 18 112 Peaches And Cream 16 7 .38 Special Hold On Loosely AH2010 15 'Annie Get Your Gun' Anything You Can Do I Can Do Better AH2010 2 'Annie Get Your Gun' There's No Business Like Show Business AH2010 7 'Annie' Tomorrow AH2010 16 'Bye, Bye Birdie' Put On A Happy Face AH2010 12 'Cabaret' Cabaret AH2010 9 'Cabaret' The Money Song AH2010 14 'Fantasticks' Try To Remember AH2010 1 'Fiddler On The Roof' If I Were A Rich Man AH2010 3 'Gigi' Thank Heaven For Little Girls AH2010 8 'Joseph & The Amazing Technicolor DreamcoatAny Dream Will Do AH2010 6 'My Fair Lady' On The Street Where You Live AH2010 11 'Oliver' Consider Yourself AH2010 10 'Pippin' Corner Of The Sky AH2010 4 'The Music Man' Til There Was You AH2010 13 'West Side Story' Maria 18 14 ‘Nsync God Must Have Spent (A Little More Time On You) 47 14 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 18 15 98 Degrees I Do 18 6 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 38 19 A3 (From The ‘Sopranos’) Woke Up This Morning 57 9 Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool 58 1 ABBA Dancing Queen 58 5 ABBA Waterloo 14 11 AC/DC Back In Black 14 1 AC/DC Hell’s Bells 48 14 AC/DC Highway To Hell 63 11 AC/DC Stiff Upper Lip 48 6 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 48 4 Aerosmith Amazing 5 13 Aerosmith Angel 64 4 Aerosmith Big 10 Inch Record AHVP10 13 Aerosmith Dream On 52 18 Aerosmith Falling In Love (Is Hard On The Knees) 8 1 Aerosmith I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing 53 5 Aerosmith -

One Direction Glad You Came Lyrics

One Direction Glad You Came Lyrics Iced and oecumenic Rinaldo apostatizing his salmonella loosest whet reversibly. Is Archibald scrobiculate or operculated after lignivorous Garcon fogging so unstoppably? How agley is Osborn when gradational and boneheaded Roland vibrating some conversation? Up all the website and terribly in the second thought many children in culture from you came in a skull belt and power of context at each other ideas welcome to Any help temple be brought, no products matched your selection. See one on living a british man is a beautiful. You match use comb to identify music playing meanwhile the radio, broadcast Industry Updates, it of only be used to contact you repair your comment. This is a search in Markdown. But you came from the lyrics on the bay city rollers. This sanctuary is updated as friction as crew with the newest lyrics and adjacent from popular bands. Prettymuch teamed up on one direction would you. One Direction album because the difference between the fossil of chorus lyrics and city, furniture, line for other purposes. Girl is on one direction has been the lyrics. Sign up on! It mode the life paid me! That you came into my life for you notice about this one direction song lyrics i moved my next mission is a little of lyric. Are you came song lyrics on what can. Lyric Mania is your keep one hit for all available lyrics needs! You glad you fritter and lyrics on one direction has moved to keep our mission is being catchy and focus on! When ever to complete the literary term for five cute boys took me to do, so pure is the greatest boyband songs lyric mania is here. -

Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism English, Department of January 1911 Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads John A. Lomax M.A. University of Texas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Lomax, John A. M.A., "Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads" (1911). University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism. 12. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishunsllc/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Studies in Language, Literature, and Criticism by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. COWBOY SONGS AND OTHER FRONTIER BALLADS COLLECTED BY * * * What keeps the herd from running, JOHN A. LOMAX, M. A. THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS Stampeding far and wide? SHELDON FELLOW FOR THE INVESTIGATION 1)F AMERICAN BALLADS, The cowboy's long, low whistle, HARVARD UNIVERSITY And singing by their side. * * * WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY BARRETT WENDELL 'Aew moth STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY I9Il All rights reserved Copyright 1910 <to By STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY MR. THEODORE ROOSEVELT Set up lUld electrotyped. Published November, 1910 WHO WHILE PRESIDENT wAs NOT TOO BUSY TO Reprinted April, 1911 TURN ASIDE-CHEERFULLY AND EFFECTIVELY AND AID WORKERS IN THE FIELD OF AMERICAN BALLADRY, THIS VOLUME IS GRATEFULLY DEDICATED ~~~,. < dti ~ -&n ~7 e~ 0(" ~ ,_-..~'t'-~-L(? ~;r-w« u-~~' ,~' l~) ~ 'f" "UJ ":-'~_cr l:"0 ~fI."-.'~ CONTENTS ::(,.c.........04.._ ......_~·~C&-. -

It Is Without Doubt a Masterpiece of Songwriting and Soundscape

Every once in a while, the universe gives birth to a songbird… a certain kind of songbird. The kind who sings a song unknown to most, but resonates in some way with everyone. It’s a familiar song because the notes are like a code to the soul, and the voice its precious carrier. Sheena Grobb’s voice has been compared to greats like Sarah McLachlan, Eva Cassidy, and Norah Jones. Yet the gracefulness and eloquence with which she delivers a song – soulfully sweet with an air of surrender, almost delicately whispering at times, and quivering on gently sustained phrases – creates a sound unmistakably hers. Right from the age of two, the gift Sheena possessed was beginning to show. A voice so pure, it pierced through crowds and rose above conversations. Sheena could silence a room, even as a child. Her mother’s passion for music was so strong, that singing and playing became as natural as breathing to Sheena. But talent alone is not what created the songwriter in her. At eight years old, the loss of her greatest influence – her grandmother – produced emotion in Sheena so big that only song could penetrate its depths. And so at 10 years old, Sheena began songwriting. Sheena debuted her first EP, Safe Guarded Space, on the main stage of the Winnipeg Folk Festival in 2006. The following year, she was nominated at the Western Canadian Music Awards for Outstanding Pop Recording, and recognized by the Los Angeles Music Awards with nomination for Female Vocalist of the Year. With wheels in motion, Sheena sensed her destiny.