Techniqes of Surrealism: a Study in Two Novels by Thomas Pynchon, V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Pynchon: a Brief Chronology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 6-23-2005 Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology Paul Royster University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Royster, Paul, "Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology" (2005). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Thomas Pynchon A Brief Chronology 1937 Born Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr., May 8, in Glen Cove (Long Is- land), New York. c.1941 Family moves to nearby Oyster Bay, NY. Father, Thomas R. Pyn- chon Sr., is an industrial surveyor, town supervisor, and local Re- publican Party official. Household will include mother, Cathe- rine Frances (Bennett), younger sister Judith (b. 1942), and brother John. Attends local public schools and is frequent contributor and columnist for high school newspaper. 1953 Graduates from Oyster Bay High School (salutatorian). Attends Cornell University on scholarship; studies physics and engineering. Meets fellow student Richard Fariña. 1955 Leaves Cornell to enlist in U.S. Navy, and is stationed for a time in Norfolk, Virginia. Is thought to have served in the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. 1957 Returns to Cornell, majors in English. Attends classes of Vladimir Nabokov and M. -

Networking Surrealism in the USA. Agents, Artists and the Market

151 Toward a New “Human Consciousness”: The Exhibition “Adventures in Surrealist Painting During the Last Four Years” at the New School for Social Research in New York, March 1941 Caterina Caputo On January 6, 1941, the New School for Social Research Bulletin announced a series of forthcoming surrealist exhibitions and lectures (fig. 68): “Surrealist Painting: An Adventure into Human Consciousness; 4 sessions, alternate Wednesdays. Far more than other modern artists, the Surrea- lists have adventured in tapping the unconscious psychic world. The aim of these lectures is to follow their work as a psychological baro- meter registering the desire and impulses of the community. In a series of exhibitions contemporaneous with the lectures, recently imported original paintings are shown and discussed with a view to discovering underlying ideas and impulses. Drawings on the blackboard are also used, and covered slides of work unavailable for exhibition.”1 From January 22 to March 19, on the third floor of the New School for Social Research at 66 West Twelfth Street in New York City, six exhibitions were held presenting a total of thirty-six surrealist paintings, most of which had been recently brought over from Europe by the British surrealist painter Gordon Onslow Ford,2 who accompanied the shows with four lectures.3 The surrealist events, arranged by surrealists themselves with the help of the New School for Social Research, had 1 New School for Social Research Bulletin, no. 6 (1941), unpaginated. 2 For additional biographical details related to Gordon Onslow Ford, see Harvey L. Jones, ed., Gordon Onslow Ford: Retrospective Exhibition, exh. -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

Staff Picks – 1960'S Literature

Staff Picks – 1960’s Literature Trout Fishing in America by Richard Brautigan Adult Fiction An indescribable romp, the novel is best summed up in one word: mayonnaise. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote 364.152 On November 15, 1959, in the small town of Holcomb, Kansas, four members of the Clutter family were savagely murdered by blasts from a shotgun held a few inches from their faces. There was no apparent motive for the crime, and there were almost no clues. Five years, four months and twenty-nine days later, on April 14, 1965, Richard Eugene Hickock, aged thirty-three, and Perry Edward Smith, aged thirty-six, were hanged for the crime on a gallows in a warehouse in the Kansas State Penitentiary in Lansing, Kansas. In Cold Blood is the story of the lives and deaths of these six people. The Reivers by William Faulkner Adult Fiction This grand misadventure is the story of three unlikely thieves, or reivers: 11-year-old Lucius Priest and two of his family's retainers. In 1905, these three set out from Mississippi for Memphis in a stolen motorcar. The astonishing and complicated results reveal Faulkner as a master of the picaresque. The Magus By John Fowles Adult Fiction The story of Nicholas Urfe, a young Englishman who accepts a teaching assignment on a remote Greek island. There his friendship with a local millionaire evolves into a deadly game, one in which reality and fantasy are deliberately manipulated, and Nicholas must fight for his sanity and his very survival. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Marquez Adult Fiction Telling the story of the rise and fall, birth and death of the mythical town of Macondo through the history of the Buendía family, this novel chronicles the irreconcilable conflict between the desire for solitude and the need for love. -

Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness

summer 1998 number 9 $5 TREASON TO WHITENESS IS LOYALTY TO HUMANITY Race Traitor Treason to whiteness is loyaltyto humanity NUMBER 9 f SUMMER 1998 editors: John Garvey, Beth Henson, Noel lgnatiev, Adam Sabra contributing editors: Abdul Alkalimat. John Bracey, Kingsley Clarke, Sewlyn Cudjoe, Lorenzo Komboa Ervin.James W. Fraser, Carolyn Karcher, Robin D. G. Kelley, Louis Kushnick , Kathryne V. Lindberg, Kimathi Mohammed, Theresa Perry. Eugene F. Rivers Ill, Phil Rubio, Vron Ware Race Traitor is published by The New Abolitionists, Inc. post office box 603, Cambridge MA 02140-0005. Single copies are $5 ($6 postpaid), subscriptions (four issues) are $20 individual, $40 institutions. Bulk rates available. Website: http://www. postfun. com/racetraitor. Midwest readers can contact RT at (312) 794-2954. For 1nformat1on about the contents and ava1lab1l1ty of back issues & to learn about the New Abol1t1onist Society v1s1t our web page: www.postfun.com/racetraitor PostF un is a full service web design studio offering complete web development and internet marketing. Contact us today for more information or visit our web site: www.postfun.com/services. Post Office Box 1666, Hollywood CA 90078-1666 Email: [email protected] RACE TRAITOR I SURREALIST ISSUE Guest Editor: Franklin Rosemont FEATURES The Chicago Surrealist Group: Introduction ....................................... 3 Surrealists on Whiteness, from 1925 to the Present .............................. 5 Franklin Rosemont: Surrealism-Revolution Against Whiteness ............ 19 J. Allen Fees: Burning the Days ......................................................3 0 Dave Roediger: Plotting Against Eurocentrism ....................................32 Pierre Mabille: The Marvelous-Basis of a Free Society ...................... .40 Philip Lamantia: The Days Fall Asleep with Riddles ........................... .41 The Surrealist Group of Madrid: Beyond Anti-Racism ...................... -

Cat151 Working.Qxd

Catalogue 151 election from Ars Libri’s stock of rare books 2 L’ÂGE DU CINÉMA. Directeur: Adonis Kyrou. Rédacteur en chef: Robert Benayoun. No. 4-5, août-novembre 1951. Numéro spé cial [Cinéma surréaliste]. 63, (1)pp. Prof. illus. Oblong sm. 4to. Dec. wraps. Acetate cover. One of 50 hors commerce copies, desig nated in pen with roman numerals, from the édition de luxe of 150 in all, containing, loosely inserted, an original lithograph by Wifredo Lam, signed in pen in the margin, and 5 original strips of film (“filmomanies symptomatiques”); the issue is signed in colored inks by all 17 contributors—including Toyen, Heisler, Man Ray, Péret, Breton, and others—on the first blank leaf. Opening with a classic Surrealist list of films to be seen and films to be shunned (“Voyez,” “Voyez pas”), the issue includes articles by Adonis Kyrou (on “L’âge d’or”), J.-B. Brunius, Toyen (“Confluence”), Péret (“L’escalier aux cent marches”; “La semaine dernière,” présenté par Jindrich Heisler), Gérard Legrand, Georges Goldfayn, Man Ray (“Cinémage”), André Breton (“Comme dans un bois”), “le Groupe Surréaliste Roumain,” Nora Mitrani, Jean Schuster, Jean Ferry, and others. Apart from cinema stills, the illustrations includes work by Adrien Dax, Heisler, Man Ray, Toyen, and Clovis Trouille. The cover of the issue, printed on silver foil stock, is an arresting image from Heisler’s recent film, based on Jarry, “Le surmâle.” Covers a little rubbed. Paris, 1951. 3 (ARP) Hugnet, Georges. La sphère de sable. Illustrations de Jean Arp. (Collection “Pour Mes Amis.” II.) 23, (5)pp. 35 illustrations and ornaments by Arp (2 full-page), integrated with the text. -

The Permanent Rebellion of Nicolas Calas: the Trotskyist Time Forgot Wald, Alan

The Permanent Rebellion of Nicolas Calas: The Trotskyist Time Forgot Wald, Alan. Against the Current; Detroit Vol. 33, Iss. 4, (Sep/Oct 2018): 27-35. Abstract Foyers d'incendie, which has never been fully translated into English, involves a reworking of Freud's idea of the pleasure principle (behavior directed toward immediate satisfaction of instinctual drives and reduction of pain) to include a desire to change the future. [...] rather than following Freud in accepting civilization as necessary repression, Calas was adamant in posing a revolutionary alternative: "Since desire cannot simply do as it pleases, it is forced to adopt an attitude toward reality, and to this end it must either try to submit to as many of the demands of its environment as possible, or try to transform as far as possible everything in its environment which seems contrary to its desires. According to Schapiro, Breton chose van Heijenoort and Calas to defend dialectical materialism, while Schapiro arranged for Columbia philosopher of science Ernest Nagel and British logical positivist A. J. Ayer (then working for the British government on assignment in the United States) to raise objections. Exponents such as Larry Rivers, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns often drew on advertising, comic books and mundane cultural objects to convey an irony accentuating the banal aspects of United States culture. Since Pop Art used a style that was hard-edged and representational, it has been interpreted as a reaction against Abstract Expressionism, the post-World War II anti-figurative aesthetic that emphasizes spontaneous brush strokes or the dripping and splattering of paint. -

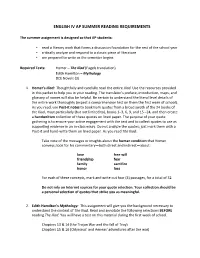

English(Iv(Ap(Summer(Reading(Requirements(

ENGLISH(IV(AP(SUMMER(READING(REQUIREMENTS( ! The(summer(assignment(is(designed(so(that(AP(students:( ( • read!a!literary!work!that!forms!a!discussion!foundation!for!the!rest!of!the!school!year! • critically!analyze!and!respond!to!a!classic!piece!of!literature! • are!prepared!to!write!as!the!semester!begins! ! Required(Texts:( Homer!–!The$Iliad!(Fagels!translation)! Edith!Hamilton!–!Mythology$ DCE!Novels!(3)! ! 1. Homer's(Iliad:$$Thoughtfully!and!carefully!read!the!entire!Iliad.!Use!the!resources!provided! in!this!packet!to!help!you!in!your!reading.!The!translator's!preface,!introduction,!maps,!and! glossary!of!names!will!also!be!helpful.!Be!certain!to!understand!the!literal!level!details!of! the!entire!work!thoroughly!(expect!a!comprehension!test!on!them!the!first!week!of!school).! As!you!read,!use!PostCit(notes!to!bookmark!quotes!from!a!broad!swath!of!the!24!books!of! the!Iliad,!most!particularly!(but!not!limited!to),!books!1–3,!6,!9,!and!15!–24,!and!then!create! a!handwritten!collection!of!these!quotes!on!lined!paper.!The!purpose!of!your!quote! gathering!is!to!ensure!your!active!engagement!with!the!text!and!to!collect!quotes!to!use!as! supporting!evidence!in!an!inSclass!essay.!Do!not!analyze!the!quotes;!just!mark!them!with!a! PostSit!and!handSwrite!them!on!lined!paper.!As!you!read!The!Iliad:! ! ! Take!note!of!the!messages!or!insights!about!the!human(condition!that!Homer! ! conveys;!look!for!his!commentary—both!direct!and!indirect—about:!! ! ( ! ! ! ! love( free(will( ( ( ( ( friendship( fear( ( ( ( ( family( sacrifice( ( ( ( ( honor( loss( ( ( !( ! ( For!each!of!these!concepts,!mark!and!write!out!four!(4)!passages,!for!a!total!of!32.! ( ((((((( Do(not(rely(on(Internet(sources(for(your(quote(selection.(Your(collection(should(be(( ( ( a(personal(selection(of(quotes(that(strike(you(as(meaningful.(( ! ( 2. -

Pynchon in Popular Magazines John K

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar English Faculty Research English 7-1-2003 Pynchon in Popular Magazines John K. Young Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/english_faculty Part of the American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Young, John K. “Pynchon in Popular Magazines.” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction 44.4 (2003): 389-404. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pynchon in Popular Magazines JOHN K. YOUNG Any devoted Pynchon reader knows that "The Secret Integration" originally appeared in The Saturday Evening Post and that portions of The Crying of Lot 49 were first serialized in Esquire and Cavalier. But few readers stop to ask what it meant for Pynchon, already a reclusive figure, to publish in these popular magazines during the mid-1960s, or how we might understand these texts today after taking into account their original sites of publica- tion. "The Secret Integration" in the Post or the excerpt of Lot 49 in Esquire produce different meanings in these different contexts, meanings that disappear when reading the later versions alone. In this essay I argue that only by studying these stories within their full textual history can we understand Pynchon's place within popular media and his responses to the consumer culture through which he developed his initial authorial image. -

Drugs and Television in Thomas Pynchon's Inherent Vice

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 "Been Hazed and Fused for So Long it's Not True" - Drugs and Television in Thomas Pynchon's Inherent Vice William F. Moffett Jr. Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Moffett, William F. Jr., ""Been Hazed and Fused for So Long it's Not True" - Drugs and Television in Thomas Pynchon's Inherent Vice". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/204 TRINITY COLLEGE Senior Thesis “Been Hazed and Fused for So Long it’s Not True” – Drugs and Television in Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice submitted by William Moffett Jr. 2012 In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in English 2012 Director: Christopher Hager Reader: James Prakash Younger Reader: Milla Riggio Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................ i Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. ii Chapter 1: “Something in the Air?” – Cultural and Pynchonian Context of Inherent Vice ........................... 1 Chapter 2: “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out” – The Interrelated -

42 CRITICS DISCUSS Ship of Fools (1962) Katherine Anne Porter (1890

42 CRITICS DISCUSS Ship of Fools (1962) Katherine Anne Porter (1890-1980) “My book is about the constant endless collusion between good and evil; I believe that human beings are capable of total evil, but no one has ever been totally good: and this gives the edge to evil. I don’t offer any solution, I just want to show this principle at work, and why none of us has any real alibi in this world.” Porter Letter to Caroline Gordon (1946) “The story of the criminal collusion of good people—people who are harmless—with evil. It happens through inertia, lack of seeing what is going on before their eyes. I watched that happen in Germany and in Spain. I saw it with Mussolini. I wanted to write about people in these predicaments.” Porter Interview, Saturday Review (31 March 1962) “This novel has been famous for years. It has been awaited through an entire literary generation. Publishers and foundations, like many once hopeful readers, long ago gave it up. Now it is suddenly, superbly, here. It would have been worth waiting for another thirty years… It is our good fortune that it comes at last still in our time. It will endure, one hardly risks anything in saying, far beyond it, for many literary generations…. Ship of Fools, universal as its reverberating implications are, is a unique imaginative achievement…. If one is to make useful comparisons of Ship of Fools with other work they should be with…the greatest novels of the past hundred years…. There are about fifty important characters, at least half of whom are major…. -

A Spatial Reading of Pynchon's California Trilogy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio della ricerca- Università di Roma La Sapienza “The Map is Not the Territory”: A Spatial Reading of Pynchon’s California Trilogy Department of European, American and Intercultural Studies Ph.D. Program in English-language Literatures Candidate: Ali Dehdarirad Supervisor: Prof. Giorgio Mariani Anno Accademico 2019-2020 Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations iv Introduction 1 Chapter One The Crying of Lot 49 9 1. Introduction: 1.1. From the Fifties to the Sixties: A Critical Moment of Change 1.2. In the Midst of a Long Decade: The American Sixties after Kennedy 14 1.3. The Counterculture as Socio-cultural Reaction to the Politics of the Sixties 18 1.4. The Sixties in Pynchon’s Works 22 2. Inside The Crying of Lot 49: Toward a Geocritical Understanding 28 SECTION 1 30 2.1. The Spatial Dimension in Pynchon’s Early Life and Career 2.2. From Pynchon’s San Narciso to California’s Orange County 34 2.2.1. Creating San Narciso: Understanding the “postmetropolitan transition” 35 2.2.2. A Historical Analogy between San Narciso and Orange County 39 2.2.3. Reading Pynchon’s San Narciso through Geocritical Lenses: Understanding The Crying of Lot 49’s Narrative Structure through Fictional and Political Spaces 41 SECTION 2 45 2.3. An Analysis of Thirdspace in Pynchon’s Fiction 2.3.1. An Attempt at Reading Pynchon’s San Narciso through Thirdspace: The Search for an Alternative Reality in The Crying of Lot 49 47 Chapter Two Vineland 54 1.