UCLA Anderson NVIDIA Corporation, 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release Notes for X11R6.8.2 the X.Orgfoundation the Xfree86 Project, Inc

Release Notes for X11R6.8.2 The X.OrgFoundation The XFree86 Project, Inc. 9February 2005 Abstract These release notes contains information about features and their status in the X.Org Foundation X11R6.8.2 release. It is based on the XFree86 4.4RC2 RELNOTES docu- ment published by The XFree86™ Project, Inc. Thereare significant updates and dif- ferences in the X.Orgrelease as noted below. 1. Introduction to the X11R6.8.2 Release The release numbering is based on the original MIT X numbering system. X11refers to the ver- sion of the network protocol that the X Window system is based on: Version 11was first released in 1988 and has been stable for 15 years, with only upwardcompatible additions to the coreX protocol, a recordofstability envied in computing. Formal releases of X started with X version 9 from MIT;the first commercial X products werebased on X version 10. The MIT X Consortium and its successors, the X Consortium, the Open Group X Project Team, and the X.OrgGroup released versions X11R3 through X11R6.6, beforethe founding of the X.OrgFoundation. Therewill be futuremaintenance releases in the X11R6.8.x series. However,efforts arewell underway to split the X distribution into its modular components to allow for easier maintenance and independent updates. We expect a transitional period while both X11R6.8 releases arebeing fielded and the modular release completed and deployed while both will be available as different consumers of X technology have different constraints on deployment. Wehave not yet decided how the modular X releases will be numbered. We encourage you to submit bug fixes and enhancements to bugzilla.freedesktop.orgusing the xorgproduct, and discussions on this server take place on <[email protected]>. -

Contributors

gems_ch001_fm.qxp 2/23/2004 11:13 AM Page xxxiii Contributors Curtis Beeson, NVIDIA Curtis Beeson moved from SGI to NVIDIA’s Demo Team more than five years ago; he focuses on the art path, the object model, and the DirectX ren- derer of the NVIDIA demo engine. He began working in 3D while attending Carnegie Mellon University, where he generated environments for playback on head-mounted displays at resolutions that left users legally blind. Curtis spe- cializes in the art path and object model of the NVIDIA Demo Team’s scene- graph API—while fighting the urge to succumb to the dark offerings of management in marketing. Kevin Bjorke, NVIDIA Kevin Bjorke works in the Developer Technology group developing and promoting next-generation art tools and entertainments, with a particular eye toward the possibilities inherent in programmable shading hardware. Before joining NVIDIA, he worked extensively in the film, television, and game industries, supervising development and imagery for Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within and The Animatrix; performing numerous technical director and layout animation duties on Toy Story and A Bug’s Life; developing games on just about every commercial platform; producing theme park rides; animating too many TV com- mercials; and booking daytime TV talk shows. He attended several colleges, eventually graduat- ing from the California Institute of the Arts film school. Kevin has been a regular speaker at SIGGRAPH, GDC, and similar events for the past decade. Rod Bogart, Industrial Light & Magic Rod Bogart came to Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) in 1995 after spend- ing three years as a software engineer at Pacific Data Images. -

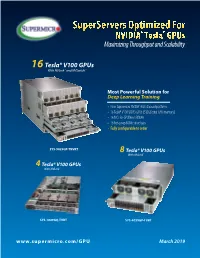

Supermicro GPU Solutions Optimized for NVIDIA Nvlink

SuperServers Optimized For NVIDIA® Tesla® GPUs Maximizing Throughput and Scalability 16 Tesla® V100 GPUs With NVLink™ and NVSwitch™ Most Powerful Solution for Deep Learning Training • New Supermicro NVIDIA® HGX-2 based platform • 16 Tesla® V100 SXM3 GPUs (512GB total GPU memory) • 16 NICs for GPUDirect RDMA • 16 hot-swap NVMe drive bays • Fully configurable to order SYS-9029GP-TNVRT 8 Tesla® V100 GPUs With NVLink™ 4 Tesla® V100 GPUs With NVLink™ SYS-1029GQ-TVRT SYS-4029GP-TVRT www.supermicro.com/GPU March 2019 Maximum Acceleration for AI/DL Training Workloads PERFORMANCE: Highest Parallel peak performance with NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs THROUGHPUT: Best in class GPU-to-GPU bandwidth with a maximum speed of 300GB/s SCALABILITY: Designed for direct interconections between multiple GPU nodes FLEXIBILITY: PCI-E 3.0 x16 for low latency I/O expansion capacity & GPU Direct RDMA support DESIGN: Optimized GPU cooling for highest sustained parallel computing performance EFFICIENCY: Redundant Titanium Level power supplies & intelligent cooling control Model SYS-1029GQ-TVRT SYS-4029GP-TVRT • Dual Intel® Xeon® Scalable processors with 3 UPI up to • Dual Intel® Xeon® Scalable processors with 3 UPI up to 10.4GT/s CPU Support 10.4GT/s • Supports up to 205W TDP CPU • Supports up to 205W TDP CPU • 8 NVIDIA® Tesla® V100 GPUs • 4 NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs • NVIDIA® NVLink™ GPU Interconnect up to 300GB/s GPU Support • NVIDIA® NVLink™ GPU Interconnect up to 300GB/s • Optimized for GPUDirect RDMA • Optimized for GPUDirect RDMA • Independent CPU and GPU thermal zones -

Amd Filed: February 24, 2009 (Period: December 27, 2008)

FORM 10-K ADVANCED MICRO DEVICES INC - amd Filed: February 24, 2009 (period: December 27, 2008) Annual report which provides a comprehensive overview of the company for the past year Table of Contents 10-K - FORM 10-K PART I ITEM 1. 1 PART I ITEM 1. BUSINESS ITEM 1A. RISK FACTORS ITEM 1B. UNRESOLVED STAFF COMMENTS ITEM 2. PROPERTIES ITEM 3. LEGAL PROCEEDINGS ITEM 4. SUBMISSION OF MATTERS TO A VOTE OF SECURITY HOLDERS PART II ITEM 5. MARKET FOR REGISTRANT S COMMON EQUITY, RELATED STOCKHOLDER MATTERS AND ISSUER PURCHASES OF EQUITY SECURITIES ITEM 6. SELECTED FINANCIAL DATA ITEM 7. MANAGEMENT S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS OF FINANCIAL CONDITION AND RESULTS OF OPERATIONS ITEM 7A. QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE DISCLOSURE ABOUT MARKET RISK ITEM 8. FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND SUPPLEMENTARY DATA ITEM 9. CHANGES IN AND DISAGREEMENTS WITH ACCOUNTANTS ON ACCOUNTING AND FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE ITEM 9A. CONTROLS AND PROCEDURES ITEM 9B. OTHER INFORMATION PART III ITEM 10. DIRECTORS, EXECUTIVE OFFICERS AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE ITEM 11. EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION ITEM 12. SECURITY OWNERSHIP OF CERTAIN BENEFICIAL OWNERS AND MANAGEMENT AND RELATED STOCKHOLDER MATTERS ITEM 13. CERTAIN RELATIONSHIPS AND RELATED TRANSACTIONS AND DIRECTOR INDEPENDENCE ITEM 14. PRINCIPAL ACCOUNTANT FEES AND SERVICES PART IV ITEM 15. EXHIBITS, FINANCIAL STATEMENT SCHEDULES SIGNATURES EX-10.5(A) (OUTSIDE DIRECTOR EQUITY COMPENSATION POLICY) EX-10.19 (SEPARATION AGREEMENT AND GENERAL RELEASE) EX-21 (LIST OF AMD SUBSIDIARIES) EX-23.A (CONSENT OF ERNST YOUNG LLP - ADVANCED MICRO DEVICES) EX-23.B -

Master Thesis

Faculty of Computer Science and Management Field of study: COMPUTER SCIENCE Specialty: Information Systems Design Master Thesis Multithreaded game engine architecture Adrian Szczerbiński keywords: game engine multithreading DirectX 12 short summary: Project, implementation and research of a multithreaded 3D game engine architecture using DirectX 12. The goal is to create a layered architecture, parallelize it and compare the results in order to state the usefulness of multithreading in game engines. Supervisor ...................................................... ............................ ……………………. Title/ degree/ name and surname grade signature The final evaluation of the thesis Przewodniczący Komisji egzaminu ...................................................... ............................ ……………………. dyplomowego Title/ degree/ name and surname grade signature For the purposes of archival thesis qualified to: * a) Category A (perpetual files) b) Category BE 50 (subject to expertise after 50 years) * Delete as appropriate stamp of the faculty Wrocław 2019 1 Streszczenie W dzisiejszych czasach, gdy społeczność graczy staje się coraz większa i stawia coraz większe wymagania, jak lepsza grafika, czy ogólnie wydajność gry, pojawia się potrzeba szybszych i lepszych silników gier, ponieważ większość z obecnych jest albo stara, albo korzysta ze starych rozwiązań. Wielowątkowość jest postrzegana jako trudne zadanie do wdrożenia i nie jest w pełni rozwinięta. Programiści często unikają jej, ponieważ do prawidłowego wdrożenia wymaga wiele pracy. Według mnie wynikający z tego wzrost wydajności jest warty tych kosztów. Ponieważ nie ma wielu silników gier, które w pełni wykorzystują wielowątkowość, celem tej pracy jest zaprojektowanie i zaproponowanie wielowątkowej architektury silnika gry 3D, a także przedstawienie głównych systemów używanych do stworzenia takiego silnika gry 3D. Praca skupia się na technologii i architekturze silnika gry i jego podsystemach wraz ze strukturami danych i algorytmami wykorzystywanymi do ich stworzenia. -

Energy-Efficient VLSI Architectures for Next

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Energy-Efficient VLSI Architectures for Next- Generation Software-Defined and Cognitive Radios A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering by Fang-Li Yuan 2014 c Copyright by Fang-Li Yuan 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Energy-Efficient VLSI Architectures for Next- Generation Software-Defined and Cognitive Radios by Fang-Li Yuan Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Dejan Markovic,´ Chair Dedicated radio hardware is no longer promising as it was in the past. Today, the support of diverse standards dictates more flexible solutions. Software-defined radio (SDR) provides the flexibility by replacing dedicated blocks (i.e. ASICs) with more general processors to adapt to various functions, standards and even allow mutable de- sign changes. However, such replacement generally incurs significant efficiency loss in circuits, hindering its feasibility for energy-constrained devices. The capability of dy- namic and blind spectrum analysis, as featured in the cognitive radio (CR) technology, makes chip implementation even more challenging. This work discusses several design techniques to achieve near-ASIC energy effi- ciency while providing the flexibility required by software-defined and cognitive radios. The algorithm-architecture co-design is used to determine domain-specific dataflow ii structures to achieve the right balance between energy efficiency and flexibility. The flexible instruction-set-architecture (ISA), the multi-scale interconnects, and the multi- core dynamic scheduling are also proposed to reduce the energy overhead. We demon- strate these concepts on two real-time blind classification chips for CR spectrum anal- ysis, as well as a 16-core processor for baseband SDR signal processing. -

GPU Developments 2018

GPU Developments 2018 2018 GPU Developments 2018 © Copyright Jon Peddie Research 2019. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without written permission from Jon Peddie Research. This report is the property of Jon Peddie Research (JPR) and made available to a restricted number of clients only upon these terms and conditions. Agreement not to copy or disclose. This report and all future reports or other materials provided by JPR pursuant to this subscription (collectively, “Reports”) are protected by: (i) federal copyright, pursuant to the Copyright Act of 1976; and (ii) the nondisclosure provisions set forth immediately following. License, exclusive use, and agreement not to disclose. Reports are the trade secret property exclusively of JPR and are made available to a restricted number of clients, for their exclusive use and only upon the following terms and conditions. JPR grants site-wide license to read and utilize the information in the Reports, exclusively to the initial subscriber to the Reports, its subsidiaries, divisions, and employees (collectively, “Subscriber”). The Reports shall, at all times, be treated by Subscriber as proprietary and confidential documents, for internal use only. Subscriber agrees that it will not reproduce for or share any of the material in the Reports (“Material”) with any entity or individual other than Subscriber (“Shared Third Party”) (collectively, “Share” or “Sharing”), without the advance written permission of JPR. Subscriber shall be liable for any breach of this agreement and shall be subject to cancellation of its subscription to Reports. Without limiting this liability, Subscriber shall be liable for any damages suffered by JPR as a result of any Sharing of any Material, without advance written permission of JPR. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case M:07-cv-01826-WHA Document 249 Filed 11/08/2007 Page 1 of 34 1 BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER LLP WILLIAM A. ISAACSON (pro hac vice) 2 5301 Wisconsin Ave. NW, Suite 800 Washington, D.C. 20015 3 Telephone: (202) 237-2727 Facsimile: (202) 237-6131 4 Email: [email protected] 5 6 BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER LLP BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER LLP JOHN F. COVE, JR. (CA Bar No. 212213) PHILIP J. IOVIENO (pro hac vice) 7 DAVID W. SHAPIRO (CA Bar No. 219265) ANNE M. NARDACCI (pro hac vice) KEVIN J. BARRY (CA Bar No. 229748) 10 North Pearl Street 8 1999 Harrison St., Suite 900 4th Floor Oakland, CA 94612 Albany, NY 12207 9 Telephone: (510) 874-1000 Telephone: (518) 434-0600 Facsimile: (510) 874-1460 Facsimile: (518) 434-0665 10 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 11 [email protected] 12 Attorneys for Plaintiff Jordan Walker Interim Class Counsel for Direct Purchaser 13 Plaintiffs 14 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 16 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 17 18 IN RE GRAPHICS PROCESSING UNITS ) Case No.: M:07-CV-01826-WHA ANTITRUST LITIGATION ) 19 ) MDL No. 1826 ) 20 This Document Relates to: ) THIRD CONSOLIDATED AND ALL DIRECT PURCHASER ACTIONS ) AMENDED CLASS ACTION 21 ) COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATION OF ) SECTION 1 OF THE SHERMAN ACT, 15 22 ) U.S.C. § 1 23 ) ) 24 ) ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED 25 ) ) 26 ) ) 27 ) 28 THIRD CONSOLIDATED AND AMENDED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT BY DIRECT PURCHASERS M:07-CV-01826-WHA Case M:07-cv-01826-WHA Document 249 Filed 11/08/2007 Page 2 of 34 1 Plaintiffs Jordan Walker, Michael Bensignor, d/b/a Mike’s Computer Services, Fred 2 Williams, and Karol Juskiewicz, on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated in the 3 United States, bring this action for damages and injunctive relief under the federal antitrust laws 4 against Defendants named herein, demanding trial by jury, and complaining and alleging as 5 follows: 6 NATURE OF THE CASE 7 1. -

Setup Sheet Sku : Xs71hd Brand

DIAMOND MULTIMEDIA - SETUP SHEET ENG APVD - l 2013-03-01 SKU : XS71HD MRKTG APVD - l 2013-03-05 BRAND : XtremeSound May 6, 2013 - 4:22 pm SKU XS71HD PRODUCT DIAMOND Xtreme Sound 7.1 PCI-e low profile 24 bit record and playback internal sound card PRODUCT CATEGORY Sound Card PRODUCT USAGE PRODUCT DETAILED DESCRIPTION Improve Your Sound Experience for Gaming, Movies, Music and more! Diamond Xtreme Sound allows the user to experience high level, theater quality sound while watching videos, listening to music, and playing games all in true 7.1 channel surround sound. This is an essential upgrade for anyone interested in increasing their computer audio experience while freeing up valuable computer system resources. Digital Optical Output: provides a multichannel, pure digital, distortion-free signal that can be connected via a single optical digital cable thus eliminating multiple cable connections and ensuring high fidelity audio for your home theater experience. PRODUCT FEATURES ● Supports 24bit 192KHz/96KHz/48KHz/44.1KHz Playback (THS -90dB and SNR 100dB ● Supports 24bit 192KHz/96KHz/48KHz/44.1KHz Recording (THS -85dB and SNR 100dB ● 7.1 Channel Audio Output ● Anti-Pop protection circuitry ● Easy Connection to Home Audio Equipment ● Special Effects Including Concert Hall and More ● Total Gaming Surround Sound Experience PRODUCT SPECIFICATIONS ● Supports 7.1 channel output, 4 sets of 3.5mm stereo outputs for front R/L, rear R/L, side R/L and center/subwoofer ● 3.5mm stereo connectors for line-in ● Two RCA connectors for coaxial input and -

SIMD Extensions

SIMD Extensions PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 12 May 2012 17:14:46 UTC Contents Articles SIMD 1 MMX (instruction set) 6 3DNow! 8 Streaming SIMD Extensions 12 SSE2 16 SSE3 18 SSSE3 20 SSE4 22 SSE5 26 Advanced Vector Extensions 28 CVT16 instruction set 31 XOP instruction set 31 References Article Sources and Contributors 33 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 34 Article Licenses License 35 SIMD 1 SIMD Single instruction Multiple instruction Single data SISD MISD Multiple data SIMD MIMD Single instruction, multiple data (SIMD), is a class of parallel computers in Flynn's taxonomy. It describes computers with multiple processing elements that perform the same operation on multiple data simultaneously. Thus, such machines exploit data level parallelism. History The first use of SIMD instructions was in vector supercomputers of the early 1970s such as the CDC Star-100 and the Texas Instruments ASC, which could operate on a vector of data with a single instruction. Vector processing was especially popularized by Cray in the 1970s and 1980s. Vector-processing architectures are now considered separate from SIMD machines, based on the fact that vector machines processed the vectors one word at a time through pipelined processors (though still based on a single instruction), whereas modern SIMD machines process all elements of the vector simultaneously.[1] The first era of modern SIMD machines was characterized by massively parallel processing-style supercomputers such as the Thinking Machines CM-1 and CM-2. These machines had many limited-functionality processors that would work in parallel. -

Driver Riva Tnt2 64

Driver riva tnt2 64 click here to download The following products are supported by the drivers: TNT2 TNT2 Pro TNT2 Ultra TNT2 Model 64 (M64) TNT2 Model 64 (M64) Pro Vanta Vanta LT GeForce. The NVIDIA TNT2™ was the first chipset to offer a bit frame buffer for better quality visuals at higher resolutions, bit color for TNT2 M64 Memory Speed. NVIDIA no longer provides hardware or software support for the NVIDIA Riva TNT GPU. The last Forceware unified display driver which. version now. NVIDIA RIVA TNT2 Model 64/Model 64 Pro is the first family of high performance. Drivers > Video & Graphic Cards. Feedback. NVIDIA RIVA TNT2 Model 64/Model 64 Pro: The first chipset to offer a bit frame buffer for better quality visuals Subcategory, Video Drivers. Update your computer's drivers using DriverMax, the free driver update tool - Display Adapters - NVIDIA - NVIDIA RIVA TNT2 Model 64/Model 64 Pro Computer. (In Windows 7 RC1 there was the build in TNT2 drivers). http://kemovitra. www.doorway.ru Use the links on this page to download the latest version of NVIDIA RIVA TNT2 Model 64/Model 64 Pro (Microsoft Corporation) drivers. All drivers available for. NVIDIA RIVA TNT2 Model 64/Model 64 Pro - Driver Download. Updating your drivers with Driver Alert can help your computer in a number of ways. From adding. Nvidia RIVA TNT2 M64 specs and specifications. Price comparisons for the Nvidia RIVA TNT2 M64 and also where to download RIVA TNT2 M64 drivers. Windows 7 and Windows Vista both fail to recognize the Nvidia Riva TNT2 ( Model64/Model 64 Pro) which means you are restricted to a low. -

Setup Sheet Sku : Mspbt300s Brand

DIAMOND MULTIMEDIA - SETUP SHEET ENG APVD - L 2012-11-20 SKU : MSPBT300S MRKTG APVD - L 2012-11-23 BRAND : GearByDiamond January 30, 2013 - 3:43 pm SKU MSPBT300S PRODUCT DIAMOND MSPBT300S Mobile Portable Wireless Bluetooth Speaker with Micro SD / TF card and 3.5mm Audio Plug for iPhone, iPad smartphone and all other Bluetooth devices (Silver) PRODUCT CATEGORY Audio PRODUCT USAGE ● From any Bluetooth enabled device, wirelessly stream and share your music anytime and anywhere. ● Turn your mobile smart phone into a hands free Bluetooth communications device. ● Use as a standalone MP3 player (Micro SD / TF card interface) PRODUCT DETAILED DESCRIPTION You no longer have to compromise performance in your portable audio experience. The Diamond Mini Rocker Bluetooth Wireless Portable Mobile Speaker is a pocket sized power house. Combined with Bluetooth wireless streaming, also included is a standard 3.5mm audio cable for your wired audio devices. Wireless or wired. You don’t have to worry about carrying extra pieces or cords getting tangled. One charge provides 8 to 10 hours of playing time. Perfect for MP3 players, smart phones, portable CD players, net books, laptops, and desktop computers. PRODUCT FEATURES Wireless stream music Full-range sound from a small Bluetooth® speaker. Enjoy hands free communication and wireless stream your music from iPad®, iPad® mini, iPhone®, Smartphone and all other Bluetooth® devices by using built in Bluetooth® technology. Plays music up to 10M away from your Bluetooth®-enabled Smartphone or tablet. Answer phones Answer incoming calls by pushing the call button on t wireless speaker. Support calls making with hands free mobile phone.