Weak Feelings: Femininity, Affect, and Sexuality in Modern Fiction and Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Double-Reading Vita Sackville-West's the Edwardians Through Freud and Foucault

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Repression/Incitement: Double-Reading Vita Sackville-West's The Edwardians Through Freud and Foucault Aimee Elizabeth Coley University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Coley, Aimee Elizabeth, "Repression/Incitement: Double-Reading Vita Sackville-West's The Edwardians Through Freud and Foucault" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3044 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Repression/Incitement: Double-reading Vita Sackville-West‟s The Edwardians through Freud and Foucault by Aimee Coley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Hirsh, Ph.D. Tova Cooper, Ph.D. Susan Mooney, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 21, 2011 Keywords: discourse, power, psychoanalysis, subjectivity, unconscious Copyright © 2011, Aimee Coley i Table of Contents Abstract ii Preface: Psychoanalysis and The Edwardians 1 Part One: Repression: Reading The Edwardians through Freud 7 Part Two: Incitement: Reading The Edwardians through Foucault 22 Afterword: Freud with Foucault 33 Definitions 34 Functions 35 Rapprochement 36 Bibliography 39 ii Abstract Vita Sackville-West‟s autobiographical novel The Edwardians lends itself to a double reading: both Freudian and Foucauldian. -

Writing Adolescence: Coming of Age in and Through

Writing Adolescence: Coming of Age in and Through What Maisie Knew, Lolita, and Wide Sargasso Sea Author[s]: Amy Lankester-Owen Source: MoveableType, Vol.1, ‘Childhood and Adolescence’ (2005) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.003 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2005 Amy Lankester-Owen. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Writing Adolescence: Coming of Age in and Through What Maisie Knew, Lolita, and Wide Sargasso Sea Amy Lankester-Owen Introduction Adolescence, the transition from childhood to adulthood, is a turbulent time of rapid physical growth and sexual development. It also constitutes a critical phase in the formation of identity and vocation. In what follows I shall explore the ways in which representations of adolescence in three literary novels – Henry James’s What Maisie Knew (1897), Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955), and Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) – both reflect and shape their authors’ writing lives. My analysis is supported throughout by psychological theories of adolescence, and draws in particular on the psychosocial developmental theory of Erik H. Erikson. In their autobiographies Henry James, Vladimir Nabokov, and Jean Rhys each participate in different ways in the literary tradition of ‘auto/biographical’ writing identified by Laura Marcus.[1] All three authors stress the importance of adolescence as a defining and critical period in their own writing lives. -

HELENA BASEBALL TEAM SHOWS up STRONG Ml

1 HELENA BASEBALL TEAM SHOWS UP STRONG 1 W"ry I mL-- SHIPMENT CITY BANKS ORGANIZE OPENING TRACK AND HELENA DEFEATS 1 A BASEBALL LEAGUE HORSES ARRIVE FIELD MET OP YEAR IF OCCIDENTAL TEAM L Six Are Institutions Represen- Logan Agricultural College yest Brings in Five of Lucky" and Will ted Play Every Will Meet University on Colli, Windy Day Prevents Boys I : Baldwin's Famous Turf Saturday. Cuinmings Field." From Plaving Fast. ! Ball. f An Interesting serlos of busehnll games is promised during the coming season by Everything is In readiness for the track kEENE the six teams recently organized by tho meet to bo held Friday afternoon on Cum-mln- BROTHERS HAVE City JOHNSON'S TWISTERS elerlts ot the various banks, under field between the University of I f SHIPPED THEIR STRING thu auspices of the Salt 7nl;: chapter of the American Institute of Banking. U Utah and the Utah Agricultural college, TOO MUCH FOR LOCALS M. McConnlfuv. tho jowelor, lias donated Promptly at 3 p. m the teams will line a handsome silver cup, to lie presented up for their to the winning team of the league. llrst baseball game of the torses Will All Arrive Before Games were Saturday, April 17, season, and at the same time Starter i'Langford Plays Sensational J, started Callahan will ; In a small way. and the end of cverv send the sprinters awav for End of Next Week From week during the rest of tho summer will the flrsl event In a dual track neet. j Fielding Game, Having ijj witness great activity on the part of tho Larsen Is in line form and Is expected California. -

Context in Literary and Cultural Studies COMPARATIVE LITERATURE and CULTURE

Context in Literary and Cultural Studies COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND CULTURE Series Editors TIMOTHY MATHEWS AND FLORIAN MUSSGNUG Comparative Literature and Culture explores new creative and critical perspectives on literature, art and culture. Contributions offer a comparative, cross-cultural and interdisciplinary focus, showcasing exploratory research in literary and cultural theory and history, material and visual cultures, and reception studies. The series is also interested in language-based research, particularly the changing role of national and minority languages and cultures, and includes within its publications the annual proceedings of the ‘Hermes Consortium for Literary and Cultural Studies’. Timothy Mathews is Emeritus Professor of French and Comparative Criticism, UCL. Florian Mussgnug is Reader in Italian and Comparative Literature, UCL. Context in Literary and Cultural Studies Edited by Jakob Ladegaard and Jakob Gaardbo Nielsen First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Contributors, 2019 Images © Contributors and copyright holders named in the captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). -

John Lehmann's New Writing: the Duty to Be Tormented

John Lehmann’s New Writing: The Duty to Be Tormented Françoise Bort To cite this version: Françoise Bort. John Lehmann’s New Writing: The Duty to Be Tormented. Synergies Royaume Uni et Irlande, Synergies, 2011, The War in the Interwar, edited by Martyn Cornick, pp.63-73. halshs- 01097893 HAL Id: halshs-01097893 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01097893 Submitted on 7 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License John Lehmann’s New Writing: the Duty to be Tormented Françoise Bort Université de Bourgogne Synergies Royaume-Uni Royaume-Uni Summary: John Lehmann’s magazine New Writing, launched in 1936, may be said to give literary historians a slow-motion image of the evolution of 63-73 pp. artistic consciousness in one of the most turbulent periods of the twentieth et century. Throughout the fourteen years of its existence, encompassing the Irlande Spanish Civil War and the Second World War, the magazine covers a neglected period of transition in the evolution of modernism. Through his editorial n° 4 policy and a susceptible interpretation of the Zeitgeist, Lehmann voices the particular torments of his generation, too young to have participated in - 2011 the First World War, but deeply affected by it. -

Material Culture and the Performance of Race

Dances with Things: Material Culture and the Performance of Race The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bernstein, Robin. 2009. Dances with things: Material culture and the performance of race. Social Text 27(4): 67-94. Published Version doi:10.1215/01642472-2009-055 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3659694 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Dances with Things Material Culture and the Performance of Race Robin Bernstein In a photograph from Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manu- script Library, a light-skinned woman stands behind a larger-than-life- size caricature of an African American eating a slice of watermelon (fig. 1).1 The young man, shoeless and dressed in rags, perches on a fence. The woman poses behind the cutout; her hand gently over- laps with the caricature’s. She bares her teeth, miming her own bite from the fruit. A typed caption on the back of the image indicates that the photograph was taken at the Hotel Exposition, a gathering of pro- fessionals from the hotel industry, in New York City’s Grand Central Palace. At some point, a curator at the Beinecke penciled “c. 1930.” How might one read this ugly, enig- matic image, this chip of racial history archived at Yale? Taking a cue from Robyn Wiegman, who has influentially called for a transition from questions of “why” to “how” with regard to race, one might Figure 1. -

A Novel, by Henry James. Author of "The Awkward Age," "Daisy Miller," "An International Episode," Etc

LIU Post, Special Collections Brookville, NY 11548 Henry James Book Collection Holdings List The Ambassadors ; a novel, by Henry James. Author of "The Awkward Age," "Daisy Miller," "An International Episode," etc. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1903. First American edition. Light blue boards with dark blue diagonal-fine-ribbed stiff fabric-paper dust jacket, lettered and ruled in gilt. - A58b The American, by Henry James, Jr. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, late Ticknor and Fields, and Fields, Osgood & Company, 1877. First edition, third variant binding - in dark green cloth. Facing title page, advertisement of "Mr. James' Writings." - A4a The American, by Henry James, Jr. London: Ward, Lock & Co. [1877]. 1st English edition [unauthorized]. Publisher's advertisements before half- title page and on its verso. Advertisements on verso of title page. 15 pp of advertisements after the text and on back cover. Pictorial front cover missing. - A4b The American, by Henry James, Jr. London: Macmillan and Co., 1879. 2nd English edition (authorized). 1250 copies published. Dark blue cloth with decorative embossed bands in gilt and black across from cover. Variant green end- papers. On verso of title page: "Charles Dickens and Evans, Crystal Palace Press." Advertisements after text, 2 pp. -A4c The American Scene, by Henry James. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907. 1st edition. 1, 500 copies published. Second binding of red cross-grain cloth. " This is a remainder binding for 700 copies reported by the publisher as disposed of in 1913." Advertisements after text, 6 pp. - A63a The American Scene, by Henry James. New York and London: Harper &Brothers Publishers, 1907. -

Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Literary Anglo-Saxon

ENVIRONMENTAL HUMANITIES IN PRE-MODERN CULTURES Estes Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Heide Estes Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Environmental Humanities in Pre‑modern Cultures This series in environmental humanities offers approaches to medieval, early modern, and global pre-industrial cultures from interdisciplinary environmental perspectives. We invite submissions (both monographs and edited collections) in the fields of ecocriticism, specifically ecofeminism and new ecocritical analyses of under-represented literatures; queer ecologies; posthumanism; waste studies; environmental history; environmental archaeology; animal studies and zooarchaeology; landscape studies; ‘blue humanities’, and studies of environmental/natural disasters and change and their effects on pre-modern cultures. Series Editor Heide Estes, University of Cambridge and Monmouth University Editorial Board Steven Mentz, St. John’s University Gillian Overing, Wake Forest University Philip Slavin, University of Kent Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination Heide Estes Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: © Douglas Morse Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 944 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 838 7 doi 10.5117/9789089649447 nur 617 | 684 | 940 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The author / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Thinking Art Thinking

CRMEP Books – Thinking art – cover 232 pp. Trim size 216 x 138 mm – Spine 18 mm 4-colour, matt laminate Caroline Bassett Dave Beech art Thinking Ayesha Hameed Klara Kemp-Welch Jaleh Mansoor Christian Nyampeta Peter Osborne Ludger Schwarte Keston Sutherland Giovanna Zapperi Thinking art materialisms, labours, forms isbn 978-1-9993337-4-4 edited by CRMEP BOOKS PETER OSBORNE 9 781999 333744 Thinking art Thinking art materialisms, labours, forms edited by PETER OSBORNE Published in 2020 by CRMEP Books Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy Penrhyn Road campus, Kingston University, Kingston upon Thames, kt1 2ee, London, UK www.kingston.ac.uk/crmep isbn 978-1-9993337-4-4 (pbk) isbn 978-1-9993337-5-1 (ebook) The electronic version of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC-BYNC-ND). For more information, please visit creativecommons.org. The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Designed and typeset in Calluna by illuminati, Grosmont Cover design by Lucy Morton at illuminati Printed by Short Run Press Ltd (Exeter) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Contents Preface PETER OSBORNE ix MATERIALISMS 1 Digital materialism: six-handed, machine-assisted, furious CAROLINE bASSETT 3 2 The consolation of new materialism KESTOn sUtHeRLAnD 29 ART & LABOUR 3 Art’s anti-capitalist ontology: on the historical roots of the -

VICTORIAN LEGACY CONFERENCE Organized by Professor Martin HEWITT All Saints College, University of LEEDS, 11-13 July 2005

VICTORIAN LEGACY CONFERENCE Organized by Professor Martin HEWITT All Saints College, University of LEEDS, 11-13 July 2005 * (Session : The Victorians in the 20th century) * Françoise BORT Université Paris-Est Victorian Legacy: the Lehmanns' Instructions for Use. (Tuesday, July 12th, 2005) The Lehmann siblings, Rosamond (born in 1901) and John (born in 1907), have always boasted their illustrious Victorian literary and artistic ancestry as descendants of William and Robert Chambers. The Chambers brothers have left their hallmark in the history of publishing, not only for their companionship with Dickens or Wilkie Collins among others, but also for their own entrepreneurial achievements. They counted authors like Thackeray and Robert Browning among their closest friends, launched the Edinburgh Journal and became part and parcel of Victorian letters and intellectual life. In fact, their lives and careers display but faint resemblances with John Lehmann’s beginnings as an editor. Unlike the self-made and self-taught Chambers, John was educated at Eton and Trinity College (Cambridge), and then worked for the Hogarth Press in 1931 and 1932 before he founded his own magazine New Writing in 1936. Rosamond, for her part, became famous almost overnight in April 1927, as the author of Dusty Answer1. The novel triggered one of the most resounding literary scandals in the 1920s and came to be considered as an epitome of the Zeitgeist. Above all, John and Rosamond Lehmann had in common a profound interest in emerging artistic expression, which makes it all the more surprising to see them recalling their Victorian ancestors whenever they tackled the subject of their own commitment to the craft of letters. -

R Parr Thesis.Pdf

The Letters of Elizabeth Bowen 1934-1949 Roz Parr 1 Table of Contents Rationale.......................................................................................................................................................................3 I. Introduction..............................................................................................................................................3 II. Elizabeth Bowen....................................................................................................................................4 III. Editing Theory......................................................................................................................................6 IV. Methodology........................................................................................................................................14 Bowen’s Letters.......................................................................................................................................................24 February 2nd, 1934 to Lady Cynthia Asquith..............................................................................................24 June 18th, 1942 to John Hayward......................................................................................................25 June 21st, 1943 to Jephson O’Conor ................................................................................................27 May 24th, 1944 to Owen Rutter..........................................................................................................30 -

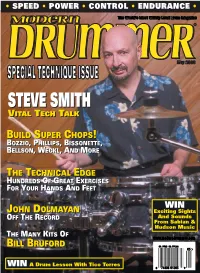

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades.