RE-Searchers-Approach.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just a Balloon Report Jan 2017

Just a Balloon BALLOON DEBRIS ON CORNISH BEACHES Cornish Plastic Pollution Coalition | January 2017 BACKGROUND This report has been compiled by the Cornish Plastic Pollution Coalition (CPPC), a sub-group of the Your Shore Network (set up and supported by Cornwall Wildlife Trust). The aim of the evidence presented here is to assist Cornwall Council’s Environment Service with the pursuit of a Public Spaces Protection Order preventing Balloon and Chinese Lantern releases in the Duchy. METHODOLOGY During the time period July to December 2016, evidence relating to balloon debris found on Cornish beaches was collected by the CPPC. This evidence came directly to the CPPC from members (voluntary groups and individuals) who took part in beach-cleans or litter-picks, and was accepted in a variety of formats:- − Physical balloon debris (latex, mylar, cords & strings, plastic ends/sticks) − Photographs − Numerical data − E mails − Phone calls/text messages − Social media posts & direct messages Each piece of separate balloon debris was logged, but no ‘double-counting’ took place i.e. if a balloon was found still attached to its cord, or plastic end, it was recorded as a single piece of debris. PAGE 1 RESULTS During the six month reporting period balloon debris was found and recorded during beach cleans at 39 locations across Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly shown here:- Cornwall has an extensive network of volunteer beach cleaners and beach cleaning groups. Many of these are active on a weekly or even daily basis, and so some of the locations were cleaned on more than one occasion during the period, whilst others only once. -

St Mawes to Cremyll Overview to Natural England’S Compendium of Statutory Reports to the Secretary of State for This Stretch of Coast

www.gov.uk/englandcoastpath England Coast Path Stretch: St Mawes to Cremyll Overview to Natural England’s compendium of statutory reports to the Secretary of State for this stretch of coast 1 England Coast Path | St Mawes to Cremyll | Overview Map A: Key Map – St Mawes to Cremyll 2 England Coast Path | St Mawes to Cremyll | Overview Report number and title SMC 1 St Mawes to Nare Head (Maps SMC 1a to SMC 1i) SMC 2 Nare Head to Dodman Point (Maps SMC 2a to SMC 2h) SMC 3 Dodman Point to Drennick (Maps SMC 3a to SMC 3h) SMC 4 Drennick to Fowey (Maps SMC 4a to SMC 4j) SMC 5 Fowey to Polperro (Maps SMC 5a to SMC 5f) SMC 6 Polperro to Seaton (Maps SMC 6a to SMC 6g) SMC 7 Seaton to Rame Head (Maps SMC 7a to SMC 7j) SMC 8 Rame Head to Cremyll (Maps SMC 8a to SMC 8f) Using Key Map Map A (opposite) shows the whole of the St Mawes to Cremyll stretch divided into shorter numbered lengths of coast. Each number on Map A corresponds to the report which relates to that length of coast. To find our proposals for a particular place, find the place on Map A and note the number of the report which includes it. If you are interested in an area which crosses the boundary between two reports, please read the relevant parts of both reports. Printing If printing, please note that the maps which accompany reports SMC 1 to SMC 8 should ideally be printed on A3 paper. -

Cornwall Council Altarnun Parish Council

CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Baker-Pannell Lisa Olwen Sun Briar Treween Altarnun Launceston PL15 7RD Bloomfield Chris Ipc Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SA Branch Debra Ann 3 Penpont View Fivelanes Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY Dowler Craig Nicholas Rivendale Altarnun Launceston PL15 7SA Hoskin Tom The Bungalow Trewint Marsh Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TF Jasper Ronald Neil Kernyk Park Car Mechanic Tredaule Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RW KATE KENNALLY Dated: Wednesday, 05 April, 2017 RETURNING OFFICER Printed and Published by the RETURNING OFFICER, CORNWALL COUNCIL, COUNCIL OFFICES, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR CORNWALL COUNCIL THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017 The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for election as Councillor for the ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL STATEMENT AS TO PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated: Decision of the Surname Other Names Home Address Description (if any) Returning Officer Kendall Jason John Harrowbridge Hill Farm Commonmoor Liskeard PL14 6SD May Rosalyn 39 Penpont View Labour Party Five Lanes Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7RY McCallum Marion St Nonna's View St Nonna's Close Altarnun PL15 7RT Richards Catherine Mary Penpont House Altarnun Launceston Cornwall PL15 7SJ Smith Wes Laskeys Caravan Farmer Trewint Launceston Cornwall PL15 7TG The persons opposite whose names no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. -

Erection of a Single Wind Turbine with Maximum Blade Tip Height of 67M (Hub Height 40M), Formation of New Vehicular Access, Access Track and Associated Infrastructure

Erection of a single wind turbine with maximum blade tip height of 67m (hub height 40m), formation of new vehicular access, access track and associated infrastructure. Land North East Of Lower Withnoe Barton, Freathy, Cornwall Cornwall Council reference PA15/08659 Objection response by No Rame Wind Turbines November 2015 Church of St. Mary and St. Julian, Maker with Rame The Robert J Barfoot Consultancy Environmental & Planning Consultants Huckleberry, East Knowstone, South Molton, Devon, EX36 4DZ Telephone: 01398 341623 Contents Introduction and background Page 1 Executive Summary Page 2 The flawed pre-application public consultation Page 6 The Written Ministerial Statement of 18 June 2015 Page 9 Landscape and visual Impacts Page 11 Shadow flicker/shadow throw Page 25 Impacts on heritage assets Page 27 Effects on tourism Page 34 Ecology issues Page 35 Noise issues Page 38 Community Benefit Page 44 The benefits of the proposal Page 46 The need for the proposal Page 51 Planning policy Page 55 Conclusions Page 62 Appendices Appendix 1 Relevant extracts from the Trenithon Farm appeal statement Appendix 2 Letter from Cornwall Council – Trenithon Farm appeal invalid Appendix 3 Tredinnick Farm Consent Order Appendix 4 Tredinnick Farm Statement of Facts and Grounds Appendix 5 Decision Notice for Higher Tremail Farm Appendix 6 Gerber High Court Judgement Appendix 7 Shadow Flicker Plan with landowner’s boundaries Appendix 8 Lower Torfrey Farm Consent Order Appendix 9 Smeather’s Farm Consent Order Appendix 10 English Heritage recommendations Appendix 11 Review by Dr Tim Reed Appendix 12 Email circulated by the PPS to the Prime Minister Appendix 13 Letter from Ed Davey to Mary Creagh MP Appendix 14 Letter from Phil Mason to Stephen Gilbert MP 1 Introduction and background 1.1 I was commissioned by No Rame Wind Turbines (NRWT) to produce a response to the application to erect a wind turbine at land north east of Lower Withnoe Barton, Freathy, Cornwall, commonly known as the Bridgemoor turbine. -

Secrets of Millbrook

SECRETS OF MILLBROOK History of Cornwall History of Millbrook Hiking Places of interest Pubs and Restaurants Cornish food Music and art Dear reader, We are a German group which created this Guide book for you. We had lots of fun exploring Millbrook and the Rame peninsula and want to share our discoveries with you on the following pages. We assembled a selection of sights, pubs, café, restaurants, history, music and arts. We would be glad, if we could help you and we wish you a nice time in Millbrook Your German group Karl Jorma Ina Franziska 1 Contents Page 3 Introduction 4 History of Cornwall 6 History of Millbrook The Tide Mill Industry around Millbrook 10 Smuggling 11 Fishing 13 Hiking and Walking Mount Edgcumbe House The Maker Church Penlee Point St. Michaels Chapel Rame Church St. Germanus 23 Eden Project 24 The Minack Theatre 25 South West Coast 26 Beaches on the Rame peninsula 29 Millbrook’s restaurants & cafes 32 Millbrook’s pubs 34 Cornish food 36 Music & arts 41 Point Europa 42 Acknowledgments 2 Millbrook, or Govermelin as it is called in the Cornish language, is the biggest village in Cornwall and located in the centre of the Rame peninsula. The current population of Millbrook is about 2300. Many locals take the Cremyll ferry or the Torpoint car ferry across Plymouth Sound to go to work, while others are employed locally by boatyards, shops and restaurants. The area also attracts many retirees from cities all around Britain. Being situated at the head of a tidal creek, the ocean has always had a major influence on life in Millbrook. -

School Admissions, for Children Born Before 1914

St Merryn School Admissions, for children born before 1914 Transcribed by Susan Old Admission Re‐admissionChristian Names Surname DOB Address Parent or Guardian Last SchoolWithdrawal Reason for leaving Remarks No. Day Month Year Day Month Year Day Month Year Day Month Year 483 9 5 1898 MilMuriel BENNETT 15 2 95 TikTrevorrick Henry Bennett None 8 3 9 Over 14 years 489 7 6 98 Mildred CARNE 19 6 93 Trevorrick John Carne None 23 12 8 Over 14 years Appointed Monitress 493 7 6 98 William TREMAINE 13 5 94 Tregolds John Tremaine None 13 1 9 Over 14 years 499 29 4 99 Harry BRENTON 9 9 93 Primrose James Brenton None 19 6 8 Over 14 years 484 9 5 98 10 4 1900 Elsie MORCUMB 26 4 95 Trevose Henry MorcumbNone 759Over 14 years 501 12 6 99 Sidney STRONGMAN 11 7 95 Shop James Strongman None 30 8 9 Over 14 years 503 15 6 99 Edwin Arnold MARTYN 12 11 95 Trevear Sarah Martyn None 14 6 9 Under bylaw engaged in agriculture 504 22 6 99 11 6 0 Clara Ellen BENNETT 27 2 95 Towan Thomas Bennet None 7 4 10 Over 14 years 509 2 4 0 Dora Mary CHAPMAN 10 2 95 Cottages Thomas ChapmanNone 839Over 14 years 510 23 4 0 Geoffry MARTYN 16 10 96 Trevear Sarah Martyn None 13 10 10 Over 14 years 511 25 4 0 William James BRAY 13 9 94 Trevear William James Bray None 11 9 8 Over 14 years 512 1 5 0 Hilda STRONGMAN 19 8 96 Shop James StrongmanNone 141010Over 14 years 523 10 6 1 Arthur Sidney BRAY 25 10 95 Lavernia Joseph Bray None 22 10 9 Over 14 years 524 11 6 1 John Thomas BRAY 20 8 96 Trevear William James Bray None 20 8 10 Over 14 years 528 17 6 1 Albert Ivy BENNETT 12 11 96 Towan Thomas Bennett None 10 11 11 Over 14 years 533 5 11 6 7 5 7 Arthur MARTYN 9 6 96 Tregella William Martyn None 18 10 9 Left neigbourhood 535 27 5 2 Lilian STRONGMAN 6 9 98 Shop James Strongman None 11 4 13 Over 14 years 536 10 6 2 Richard H JONAS 9 2 99 Trewithen Henry Jonas None 28 2 13 Over 14 years 537 16 6 2 28 8 11 Hilda M. -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

1864 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

1864 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes Table of Contents 1. Epiphany Sessions ..................................................................................................................... 1 2. Lent Assizes ............................................................................................................................. 29 3. Easter Sessions ........................................................................................................................ 74 4. Midsummer Sessions .............................................................................................................. 88 5. Summer Assizes .................................................................................................................... 104 6. Michaelmas Sessions ............................................................................................................ 134 Royal Cornwall Gazette 8 & 15 January 1864 1. Epiphany Sessions The Epiphany Quarter Sessions for the county of Cornwall were opened on Tuesday last, at Bodmin, when there were present the following magistrates:— Charles Brune Graves Sawle, Esq., Sir Colman Rashleigh, Bart., and Chairmen J. Jope Rogers, Esq., M.P. Lord Vivian. R. Foster, Esq. Hon. and Rev. J. Townshend C.B. Kingdon, Esq. Boscawen. J. Haye, Esq. T.J. Agar Robartes, Esq., M.P. W. Roberts, Esq. N. Kendall, Esq., M.P. S.U.N. Usticke, Esq. R. Davey, Esq., M.P. F.M. Williams, Esq. John St. Aubyn, Esq., M.P. W.R.C. Potter, Esq. Sir S.T. Spry. J.C.B. Lethbridge, Esq. W.H. Pole Carew, Esq. E. Collins, Esq. John Tremayne, Esq. H. Trelawny, Esq. C.P. Brune, Esq. J. Trevenen, Esq. F. Howell, Esq. E.H. Rodd, jun., Esq. D.P. Le Grice, Esq. D. Horndon, Esq. T.S. Bolitho, Esq. W. Morshead, Esq. E. Coode, jun., Esq. Rev. T. Phillpotts. F. Rodd, Esq. Rev. J. Symonds. N. Norway, Esq. Rev. V.F. Vyvyan. R.G. Lakes, Esq. Rev. J.J. Wilkinson. C.A. Reynolds, Esq. Rev. R.B. Kinsman. R.G. Bennet, Esq. Rev. J. Glanville. W. Michell, Esq. Rev. A. Tatham. J. Hichens, Esq. Rev. L.M. Peter. J.T.H. Peter, Esq. Rev. J. Glencross. E.C. -

LAND at BRIDGEMOOR FARM ST. JOHN CORNWALL Results of a Desk-Based Assessment, Geophysical Survey & Historic Visual Impact Assessment

LAND at BRIDGEMOOR FARM ST. JOHN CORNWALL Results of a Desk-Based Assessment, Geophysical Survey & Historic Visual Impact Assessment The Old Dairy Hacche Lane Business Park Pathfields Business Park South Molton Devon EX36 3LH Tel: 01769 573555 Email: [email protected] Report No.: 150511 Date: 11.05.2015 Authors: E. Wapshott J. Bampton S. Walls Land at Bridgemoor Farm, St. John, Cornwall Land at Bridgemoor Farm, St. John, Cornwall Results of a Desk-Based Assessment, Geophysical Survey & Historic Visual Impact Assessment For Nick Leaney of Aardvark EM Ltd. (the Client) By SWARCH project reference: SBF15 National Grid Reference: SX4069352393 Planning Application Ref: Pre-planning Project Director: Dr. Bryn Morris Project Officer: Dr. Samuel Walls Fieldwork Managers: Dr. Samuel Walls HVIA: Emily Wapshott Walkover Survey: Joe Bampton Geophysical Survey: Joe Bampton Desk Based Assessment: Dr. Samuel Walls; Victoria Hosegood Report: Emily Wapshott; Joe Bampton; Dr. Samuel Walls; Report Editing: Dr. Samuel Walls; Natalie Boyd Graphics: Victoria Hosegood; Joe Bampton June 2015 South West Archaeology Ltd. shall retain the copyright of any commissioned reports, tender documents or other project documents, under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 with all rights reserved, excepting that it hereby provides an exclusive licence to the client for the use of such documents by the client in all matters directly relating to the project as described in the Project Design. South West Archaeology Ltd. 2 Land at Bridgemoor Farm, St. John, Cornwall Summary This report presents the results of a desk-based assessment, walkover survey, geophysical survey and historic visual impact assessment carried out by South West Archaeology Ltd. -

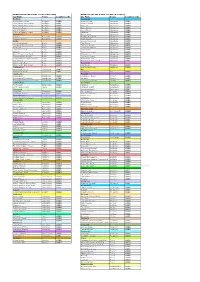

Phone-And-Pay-Location-Codes.Pdf

BEMROSE PHONE & PAY LOCATION CODES BEMROSE PHONE & PAY LOCATION CODES Car Park Town Location code Car Park Town Location code Bodmin Newquay Berrycombe Road Bodmin 8200 Albany Road Newquay 8362 Fore Street Short Stay Bodmin 8201 Atlantic Road Newquay 8363 Fore Street Long Stay Bodmin 8218 Belmont Newquay 8364 Dennison Road Bodmin 8202 Dane Road Newquay 8365 Victoria Square Bodmin 8203 Fore Street Newquay 8366 Victoria Square Coach Bodmin 8204 Harbour Newquay 8367 Boscastle Mount Wise Newquay 8368 Cobweb Boscastle 8224 Pentire Headland Newquay 8369 Cobweb Coach Boscastle 8225 Porth Beach Newquay 8432 Bude St Georges Road Newquay 8370 Crooklets Beach Bude 8205 The Manor Newquay 8371 Crooklets Beach Coach Bude 8206 Tolcarne Road Newquay 8372 Crescent Bude 8207 Towan Headland Newquay 8374 Crescent Coach Bude 8208 Tregunnel Newquay 8375 Wharf Bude 8209 Tregunnel Coach Newquay 8376 Wharf Coach Car Park Bude 8210 Trenance Newquay 8377 Summerleaze Beach Bude 8211 Trenance Coach Newquay 8378 Summerleaze Beach Coach Bude 8212 Watergate Bay Newquay 8430 Post Office Bude 8213 Watergate Bay Coach Newquay 8431 Widemouth Bay Bude 8214 Padstow Widemouth Bay Coach Bude 8215 Link Road Padstow 8227 Callington Link Road Coach Padstow 8228 New Road South Callington 8307 Par New Road North Callington 8321 Par Beach Par 8433 Camborne Penryn Rosewarne Camborne 8386 Exchequer Quay Penryn 8438 Rosewarne Extension Camborne 8408 Saracen Penryn 8337 Rosewarne Extension Coach Camborne 8409 Commercial Road Penryn 8427 Carbis Bay Penzance Porthrepta Carbis Bay 8423 Harbour -

January 2021 Master

to Hartland Welcome Cross Morwenstow Crimp 217 Kilkhampton Coombe Thurdon (school days only) 218 Stibb 218 Poughill 218 217 Bush Grimscott Bude Sea Pool Bude Red Post Stratton Upton Holsworthy Marhamchurch Wednesday only 217 Pyworthy Widemouth Bay Bridgerule Titson Coppathorne Friday only Treskinnick Cross Whitstone Week St Mary North Tamerton Crackington Haven Wainhouse Crackington Corner Monday & Thursday only Broad Boyton Tresparrett Langdon Bennacott Posts Canworthy Water Warbstow Boscastle Langdon North Trevalga Petherwin Trethevy St Nectan's Glen Tintagel Castle Bossiney Yeolmbridge Hallworthy Tintagel Egloskerry Davidstow St Stephen Camelford Trewarmett Station Launceston Castle Pipers Pool Launceston Delabole Valley Polyphant Truckle Camelford Altarnun South Helstone Petherwin Port Isaac St Teath Fivelanes Pendoggett Polzeath St Endellion Bodmin Moor Congdon’s Shop Treburley Trelill 236 Trebetherick St Minver Bolventor Pityme St Tudy St Kew Bray Shop Stoke Climsland Padstow Rock Highway Bathpool Harlyn 236 Tavistock Bodmin Moor Rilla Mill 12 12A Linkinhorne Downgate St Mabyn Constantine Upton Cross St Ann's Gunnislake Kelly Bray Chapel St Issey Whitecross Porthcothan Pensilva Bedruthan Steps Wadebridge Callington Harrowbarrow Treburrick Ashton Calstock Bodmin River Tamar Carnewas Tremar 12A St Dominick St Neot St Cleer St Eval 12 Trenance St Ive Ruthernbridge Liskeard Merrymeet St Mellion Mawgan Porth Rosenannon Winnard’s Doublebois Trevarrian St Mawgan Perch River Tamar Tregurrian Lanivet Bodmin East Taphouse Parkway Menheniot -

Click on the Link to Download the April May Issue of the Looe Community

LOOE COMMApUril N- MIaTy Y20 2N1 EWS Can YOU help to bring the Ollie Naismith II to Looe? 122nd Edition - Online Published by Looe Development Trust for Looe and surrounding parishes Higher Market Street, East Looe PL13 1BS 01503 598356 [email protected] www.thecrabbpot.co.uk and find us on Facebook Ann, Micky & Bryony welcome you to The Crabb Pot for interiors, lighting, soft furnishings,dining and kitchen, wall art and mirrors, jewellery and crafts from Cornwall and the South West, wooden toys, and stylish seaside gifts. Cards, wrapping paper and gift tokens also available. www.dolphinholidays.co.uk www.tfs-sw.co.uk NEW FROM THE EAST LOOE TOWN TRUST WOOLDOWN WORKS Regular Wooldown users have noticed the steps up from the South Coast Path to Lower Windmill Field have been replaced. Antony and Bill have made a good job of widening and levelling the steps. There are more water run-offs now which should help break the water flow during heavy rain, and make a longer lasting job. WOOLDOWN BEE GLADES Five years after the first appearance of Country Conservation’s remote controlled flail mower, they brought it back to clear the Mount Ararat and Coast Path bee glades. On the first occasion the flail mower had to deal with bracken and bramble up to six feet high, and opened up long-lost sea views from the Island to Rame. This time the job was to keep strong regrowth down and push back the encroaching old man’s beard from the margins of the glade. The bee glade conservation scheme is designed to encourage the natural regrowth of vetches and wild flowers that provide nectar for bees and butterflies.