C. Bertling Notes on Myth and Ritual in Southeast Asia In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Groningen Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece Bremmer

University of Groningen Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece Bremmer, J.N. Published in: Griechische Mythologie und Frühchristentum IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bremmer, J. N. (2005). Myth and Ritual in Ancient Greece: Observations on a Difficult Relationship. In R. von Haehling (Ed.), Griechische Mythologie und Frühchristentum (pp. 21-43). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 N. Oettinger, ‘Entstehung von Mythos aus Ritual. Das Beispiel des hethitischen textes CTH 390A’, in M. Hutter and S. Hutter-Braunsar (eds), Offizielle Religion, lokale Kulte und individuelle Religiosität (Münster, 2004) 347-56. MYTH AND RITUAL IN ANCIENT GREECE: OBSERVATIONS ON A DIFFICULT RELATIONSHIP by JAN N. -

'Myth' and 'Religion'

THOUGHTS ON MYTH AND RELIGION IN EARLY GREEK HISTORIOGRAPHY Robert L. FOWLER University of Bristol [email protected] RESUMEN: El artículo examina el nacimiento del concepto de mythos/mito en el contexto de la historiografía y la mitografía de la Grecia arcaica. La posibilidad de oponerse a relatos tradicionales es un factor crítico en este proceso y se relaciona estrechamente con los esfuerzos de los autores por fijar su autoridad. Se compara la práctica de Heródoto con la de los primeros mitógrafos y, aunque hay amplias similitudes, hay diferencias cruciales en el tratamiento de los asuntos religiosos. Los escrúpulos personales de Heródoto responden en parte a su bien conocida reserva en lo referente a los dioses, pero es también relevante su actitud acerca de la tarea del historiador y su noción de cómo los dioses intervienen en la historia. Mientras que los mitógrafos tratan de historicizar la mitología, Heródoto trata de modo notable de desmitologizar la historia, separando ambas, pero al mismo tiempo definiendo con más profundidad que nunca sus auténticas interconexiones. Esta situación sugiere algunas consideraciones generales acerca de la relación entre mito y ritual en Grecia. ABSTRACT: The article examines the emerging concept of mythos/myth in the context of early Greek historiography and mythography. The possibility of contesting traditional stories is a critical factor in this process, and is closely related to the efforts of writers to establish their authority. Herodotos’ practice is compared with that of the early mythographers, and though there are some broad similarities, there are crucial differences in their approach to religious matters. -

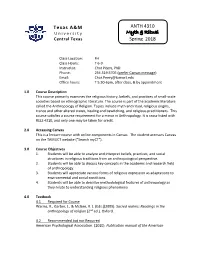

Myth and Ritual Central Texas

Texas A&M ANTH 4310 UNIVERSITY Myth and Ritual Central Texas Spring 2019 Class Location: FH 211 Class Hours: W 6-9 Instructor: Floyd Berry, PhD Office: HH 204 S Office Hours: MTWR 2-5 (please make an appointment) Email: (prefer Canvas message) [email protected] NOTE: If contacting instructor outside of Canvas, students must use their official TAMUCT emails. 1.0 Course Description Examines the religious history, beliefs, and practices of societies based on ethnographic literature. Cross-listed with RELS 4310. 2.0 Accessing Canvas This is a lecture course with online components in Canvas. The student accesses Canvas at https://tamuct.onecampus.com/ and locates the “card” for the Canvas platform. 3.0 Course Objectives 1. Students will be able to discuss different types of religious phenomena, focusing primarily on small-scale societies. 2. Students will be able to discuss the role of shamans as religious practitioners. 3. Students will be able to analyze rites of passage and the concept of liminality. 3. Students will submit prose reactions to material and topics covered in class discussions. 4. Students will gain an appreciation for the variety of religious phenomena as an aspect of different cultures and environments, based on readings, commentaries, and class discussions. 5. Students will submit acceptable essays for mid-term and final exams. To be accepted, the student shall discuss all aspects of an essay question, using standard English prose and grammatical construction. 4.0 Textbook 4.1 Required for Course Warms, R., Garber, J., & McGee, R. J. (Eds.).(2009). Sacred realms: Readings in the anthropology of religion (2nd ed.). -

16 Biblio 537 27/7/04, 11:48 AM 538 Durga’S Mosque

Bibliography 537 BIBLIOGRAPHY ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THIS BIBLIOGRAPHY LUB, MS Lor. Leiden Universiteit Bibliothek, Leiden Oriental MS BL/IO British Library/India Office library LUB/LOr Leiden Universiteit Bibliothek: Leiden Oriental manuscript KITLV Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde PNRI: KBG Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia (Indonesian National Library): Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap NBS Netherlands Bible Society, loan collection, Leiden RAS Royal Asiatic Society (London) SMP/KS Surakarta MS Project: Karaton Surakarta SMP/MN Surakarta MS Project: Mangkunagaran (Palace library) SMP/RPM Surakarta MS Project: Radyapustaka Museum, Surakarta MANUSCRIPTS Babad Mangkunagaran, LUB, MS LOr. 6781. “Bundel Slametan dan Labuhan serta Kebo Maésa Lawung”, Mangkunagaran Palace Archives. Ms. 102 Ra. Fatwa-fatwané para Pinituwa (“Councils to the Elders”). Radèn Tanoyo. 1971. Gambar2 kanthi keterangan plabuhan dalem dhumateng redi2 saha dhateng seganten kidul nuju tingalan dalem jumengan mawi 11 lembar (verjaardag van troonsbestigang) from Ir. Moens Platen Album, no. 9 Museum Pusat, Yogyakarta, ms. 934 Dj. Kraemer, H. Autograph note on prayers (donga) important slametan and the Maésa Lawung with donga’s (LUB, MS LOr. 10.846 §4). Mangkunagaran Archives M.N.VI: (box 31) In 1915 the population of Krendawahana: 127 bau of cultivated fields and only 26 bau of rice fields. Mangkunagaran Archives: (box 5.256) As a sort of terminas ad quem for deforestration by 1947 the village of Krendawahana had 139 ha. under cultivation (all classes combined) and was paying an annual tax to the Mangkunagaran of 300 guilders. Pangruwatan. Leiden Oriental Ms. 6525 (1). Pradata (Ngabèhi Arya), Klathèn 1890. Information on 67 palabuhan offerings, with Dutch notes by Rouffaer. -

ISCLR 2014 Conference Broch

1 © Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts, 2014 © International Society for Contemporary Legend Research, 2014 ISBN 978-80-7308-510-0 Perspectives on Contemporary Legend International Society for Contemporary Legend Research 32nd International Conference Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague Prague, Czech Republic Tuesday 3—Sunday 8 June, 2014 Conference Abstracts Petr Janeček – Elissa R. Henken – Elizabeth Tucker (Editors) Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague International Society for Contemporary Legend Research Prague 2014 FOREWORD Welcome to Perspectives on Contemporary Legend, the thirty-second meeting of the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research! The other members of ISCLR’s Executive Council and I are delighted that this meeting of legend scholars will take place in the beautiful city of Prague, the home of so much important history and culture. We thank our very kind hosts, Dr. Petr Janeček from the Institute of Ethnology and Dr. Mirjam Fried, Dean of the Faculty of Arts at Charles University. Their excel- lent planning and generosity will make this one of our best meetings ever. Besides presenting and discussing papers, we will enjoy an opening re- ception at the Café Louvre on Tuesday and a closing banquet at the Kolkov- na Savarin restaurant on Friday evening. Our excursion on Thursday will take us to the late medieval town of Český Krumlov, where we will visit a castle with an unusual Baroque theatre. On two other days there will be ghost tours of Prague, during which we will learn both old and contem- porary legends. In addition, we will visit Prague’s Ethnographic Museum. -

The World of Greek Religion and Mythology

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber/Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber/Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) ∙ James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) ∙ Janet Spittler (Charlottesville, VA) J. Ross Wagner (Durham, NC) 433 Jan N. Bremmer The World of Greek Religion and Mythology Collected Essays II Mohr Siebeck Jan N. Bremmer, born 1944; Emeritus Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Groningen. orcid.org/0000-0001-8400-7143 ISBN 978-3-16-154451-4 / eISBN 978-3-16-158949-2 DOI 10.1628/978-3-16-158949-2 ISSN 0512-1604 / eISSN 2568-7476 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio- graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitt- ed by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particular- ly to reproductions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset using Stempel Garamond typeface and printed on non-aging pa- per by Gulde Druck in Tübingen. It was bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. in memoriam Walter Burkert (1931–2015) Albert Henrichs (1942–2017) Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood (1945–2007) Preface It is a pleasure for me to offer here the second volume of my Collected Essays, containing a sizable part of my writings on Greek religion and mythology.1 Greek religion is not a subject that has always held my interest and attention. -

Paganism.Pdf

Pagan Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 About the Author .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Beliefs, Teachings, Wisdom and Authority ....................................................................................................................... 2 Basic Beliefs ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Sources of Authority and (lack of) scriptures ........................................................................................................................ 4 Founders and Exemplars ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ways of Living ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Guidance for life .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Ritual practice ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

![Myth and Ritual 09Gc Rel 3022 18 T 7/R 7-8 [1:55-2:45 / 1:55-3:50] 28F0 Ant 3930 18 T 7/R 7-8 and 13/And 13 I](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8363/myth-and-ritual-09gc-rel-3022-18-t-7-r-7-8-1-55-2-45-1-55-3-50-28f0-ant-3930-18-t-7-r-7-8-and-13-and-13-i-2258363.webp)

Myth and Ritual 09Gc Rel 3022 18 T 7/R 7-8 [1:55-2:45 / 1:55-3:50] 28F0 Ant 3930 18 T 7/R 7-8 and 13/And 13 I

REL3022: MYTH AND RITUAL 09GC REL 3022 18 T 7/R 7-8 [1:55-2:45 / 1:55-3:50] 28F0 ANT 3930 18 T 7/R 7-8 AND 13/AND 13 I. Instructor Dr. Robin Wright, Department of Religion. Anderson Hall 107C. II. Course Website Students are held responsible for all materials and related information posted on the course website. III. Objectives of the course: This course examines the theories and methods in the anthropological and religious studies of myths, rituals, religious specialists, and religious movements. Examples will be primarily drawn from indigenous cultures of the Americas, but also from ancient Mediterranean cultures. Students can expect to learn how to interpret the symbolism and meanings of myths and rituals. We will discuss the place of myth and ritual in both traditional and non-traditional societies and the importance of both in mediating historical change. IV. Readings and Modules: There are two books to purchase from the bookstore: The Fire of the Jaguar, by Terence S. Turner (HAU Books, Chicago, 2017); and Ritual. Perspectives and Dimensions, by Catherine Bell (Kindle e-book, Oxford University Press, 1997). All other Readings are posted in the Modules section of the website. V. Lecture and Reading Schedule: Class Schedule: 08/23: Introduction to the Course 08/28: Roy Rappaport, “The Sacred in Human Evolution” 08/30: Catherine Bell, Ritual. Perspective and Dimensions, Ch. 1,”Questions of Origin and Essence”; Tylor, “Religion in Primitive Culture”; Ackerman, “Frazer on Myth and Ritual” 09/04: C. Bell, Ritual. Ch. 2 “Questions of Social Function and Structure”; Durkheim, “The Elementary Forms of Religious Life”; Rappaport, “Ritual, Sanctity and Cybernetics”; 09/06: Bell, Ritual, Chs. -

The Problem of Defining Myth

The Problem of Defining Myth By LAURI HONKO The semantic span of the concept of myth The first thing that one realises in trying to grasp the semantic implica- tions of myth is that myth can cover an extremely wide field. Without resorting to an enumeration of the different ways in which the term is used nowadays, it is clear that myth can encompass everything from a simple-minded, fictitious, even mendacious impression to an absolutely true and sacred account, the very reality of which far outweighs anything that ordinary everyday life can offer. The way in which the term myth is commonly used reveals, too, that the word is loaded with emotional over- tones. These overtones creep not only into common parlance but also, somewhat surprisingly, into scientific usage. That myth does, in fact, carry emotional overtones in this way is perhaps most easily seen if we think of terms such as prayer, liturgy, ritual drama, spell: they are all used for different religious genres but would seem to be more neutral than myth. It appears to be difficult for many scholars to discuss myth simply as a form of religious communication, as one genre among other genres.' All attempts to define myth should, of course, be based, on the one hand, on those traditions which are actually available and which are called myths and, on the other, on the kind of language which scholars have adopted when discussing myth. In both cases, that of the empirical material and that of the history of scholarship on myth, the picture that results is far from uniform. -

Reflections from a Symbolic Analysis of Numic Origin Myths

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Myth as Ritual: Reflections from a Symbolic Analysis of Numic Origin Myths Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6tq7r6d8 Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 23(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Author Myers, L. Daniel Publication Date 2001-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 39-50 (2001) Myth as Ritual: Reflections from a Symbolic Analysis of Numic Origin Myths^ L. DANIEL MYERS Epochs Past, 339 Fairhaven Road, Tracys Landing, Maryland 20779 Among the Numic-speaking people of the Great Basin region, sacred stories or myths are told within a strict ritual setting. Within this myth-telling context, three ritual events (i.e., male puberty, female puberty, and the marriage ceremony) are examined through a symbolic analysis of 25 variants of two series of Numic origin myth. This allows for an interpretation of myth and ritual as cultural modes of symbolic expression that form levels of native realities. The various ritual processes encoded in the origin myths are identified and interpreted in an over-all context of myth as ritual. A ccording to theoretical perspectives or scholarly purposes, ritual genres occur in a variety of ./Iforms and contexts (van Gennep 1960; Turner 1967, 1969, 1974; Rappaport 1971a, 1971b, 1979). Some, for instance, demand their expression be witnessed at the group or inter-group level in both the ethnologic (e.g., rituals of intensification, calendrical rites, etc.) and strict ethnographic context (e.g., rituals of affliction, initiation rites, etc.). -

Série Antropologia 252 Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Myth

SÉRIE ANTROPOLOGIA 252 ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACHES TO THE STUDY OF MYTH Aleksandar Boskovik Brasília 1999 2 * Anthropological approaches to the study of myth Aleksandar Boskovik Departamento de Antropologia Universidade de Brasília Introduction In this paper I intend to demonstrate the influence of William Robertson Smith’s concept of myth and ritual to the anthropological study of myth. Smith was the first anthropologist to demonstrate clearly the relationship of myth and ritual — and in doing so he influenced generations of anthropologists. However, his influence was not always obvious or direct. For example, his concept of the primacy of ritual over myth was developed from the concept of religion as a social fact, which influenced Durkheim. It was through Durkheim that this concept made its way to subsequent scholarship. I will show the extent of some of Smith’s ideas that were present in the works of some of the most prominent anthropologists (and, through their work, made their way into the philosophical theories of Cassirer and Langer). Paradoxically, myth figured much more prominently in the work of Edward Tylor (1877), but lost prominence in the subsequent anthropological literature. I believe that Smith was indirectly responsible for this decline in prominence. William Robertson Smith is primarily associated with the ‘Myth and Ritual school,’1 and in this area his influence is still predominant in anthropology. In a * Acknowledgment This is an abbreviated version of my M.A. thesis (“William Robertson Smith and the Anthropological Study of Myth”), defended at the Department of Anthropology, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA (USA) in 1993. It was presented at the William Robertson Smith Congress at King’s College, Aberdeen, on April 8, 1994. -

Texas A&M ANTH 4310 Myth & Ritual Spring 2018

Texas A&M ANTH 4310 University Myth & Ritual Central Texas Spring 2018 Class Location: FH Class Hours: T 6-9 Instructor: Char Peery, PhD Phone: 254.519.5705 (prefer Canvas message) Email: [email protected] Office hours: T 5:30-6pm, after class, & by appointment 1.0 Course Description This course primarily examines the religious history, beliefs, and practices of small-scale societies based on ethnographic literature. The course is part of the academic literature called the Anthropology of Religion. Topics include myth and ritual, religious origins, trance and other altered states, healing and bewitching, and religious practitioners. This course satisfies a course requirement for a minor in Anthropology. It is cross-listed with RELS 4310, and only one may be taken for credit. 2.0 Accessing Canvas This is a lecture course with online components in Canvas. The student accesses Canvas on the TAMUCT website (“Search myCT”). 3.0 Course Objectives 1. Students will be able to analyze and interpret beliefs, practices, and social structures in religious traditions from an anthropological perspective. 2. Students will be able to discuss key concepts in the academic and research field of anthropology. 3. Students will appreciate various forms of religious expression as adaptations to environmental and social conditions. 4. Students will be able to describe methodological features of anthropology as they relate to understanding religious phenomena. 4.0 Textbook 4.1 Required for Course Warms, R., Garber, J., & McGee, R. J. (Eds.)(2009). Sacred realms: Readings in the anthropology of religion (2nd ed.). Oxford. 4.2 Recommended but not Required American Psychological Association.