Exemptions, Universities, and the Legacy of Slavery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society

JOURNAL OF tHE Presbyterian Historical Society. Vol. I., No. 4. Philadelphia, Pa. June A. D., 1902. THE EARLY EDITIONS OF WATTS'S HYMNS. By LOUIS F. BENSON, D. D. Not many books were reprinted more frequently during the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century than the Hymns and Spiritual Songs of Isaac Watts. Few books became more familiar, and certainly but few played a greater part in the history of our American Presbyterianism, both in its worship and in its strifes. But with all this familiarity and multiplica tion of editions, the early history, textual and bibliographical, of the hymns has remained practically unknown. This is ac counted for by the fact that by the time interest in such studies began to be awakened, the early editions of the book itself had disappeared from sight. As long ago as 1854, Peter Cunningham, when editing the Life of Watts in Johnson's Lives of the Poets, stated that "a first edition of his Hymns, 1707, is rarer than a first edition of the Pilgrim's Progress, of which it is said only one copy is known." The second edition is not less rare. The Rev. James Mearns, assistant editor of Julian's Dictionary of Hymnology, stated (The Guardian, London, January 29, 1902) that he had never seen or heard of a copy. Even now the British Museum possesses nothing earlier than the fifth edition of 1716. It has (265 ) THE LOG COLLEGE OF NESHAM1NY AND PRINCETON UNIVERSITY. By ELIJAH R. CRAVEN, D. D., LL, D. After long and careful examination of the subject, I am con vinced that while there is no apparent evidence of a legal con nection between the two institutions, the proof of their connec tion as schools of learning — the latter taking the place of the former — is complete. -

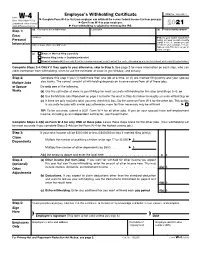

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

Preaching of the Great Awakening: the Sermons of Samuel Davies

Preaching of the Great Awakening: The Sermons of Samuel Davies by Gerald M. Bilkes I have been solicitously thinking in what way my life, redeemed from the grave, may be of most service to my dear people ... If I knew what subject has the most direct tendency to save your souls, that is the subject to which my heart would cling with peculiar endearment .... Samuel Davies.1 I. The "Great Awakening" 1. The Narrative It is customary to refer to that time period which spanned and surrounded the years 1740-1742 as the Great Awakening in North American history. The literature dedicated to the treatment of this era has developed the tradition of tracing the revival from the Middle Colonies centripetally out to the Northern Colonies and the Southern Colonies. The name of Theodorus Frelinghuysen usually inaugurates the narrative, as preliminary to the Log College, its Founder, William Tennent, and its chief Alumni, Gilbert Tennent, and his brothers John, and William Jr., Samuel and John Blair, Samuel Finley and others, so significantly portrayed in Archibald Alexander’s gripping Sketches.2 The "mind" of the revival, Jonathan Edwards, pastored at first in the Northampton region of New England, but was later drawn into the orbit of the Log College, filling the post of President for lamentably only three months. Besides the Log College, another centralizing force of this revival was the “Star from the East,” George Whitefield. His rhetorical abilities have been recognized as superior, his insight into Scripture as incisive, and his generosity of spirit boundless. The narrative of the “Great Awakening” reaches back to those passionate and fearless Puritans of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, who championed biblical and experiential religion as the singular remedy for a nation and a people clinging to forms and superstitions. -

James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Oliver Cowdery: the Irsf T Amendment and the 134Th Section of the Doctrine and Covenants Rodney K

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Review Volume 2003 | Issue 3 Article 3 9-1-2003 James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Oliver Cowdery: The irsF t Amendment and the 134th Section of the Doctrine and Covenants Rodney K. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Christianity Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Rodney K. Smith, James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Oliver Cowdery: The First Amendment and the 134th Section of the Doctrine and Covenants, 2003 BYU L. Rev. 891 (2003). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2003/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SMI-FIN 9/29/2003 10:25 PM James Madison, John Witherspoon, and Oliver Cowdery: The First Amendment and the 134th Section of the Doctrine and Covenants ∗ Rodney K. Smith A number of years ago, as I completed an article regarding the history of the framing and ratification of the First Amendment’s religion provision, I noted similarities between the written thought of James Madison and that of the 134th section of the Doctrine & Covenants, which section was largely drafted by Oliver Cowdery.1 At ∗ Herff Chair of Excellence in Law, Cecil C. -

Patrick Henry

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY PATRICK HENRY: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HARMONIZED RELIGIOUS TENSIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY BY KATIE MARGUERITE KITCHENS LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 1, 2010 Patrick Henry: The Significance of Harmonized Religious Tensions By Katie Marguerite Kitchens, MA Liberty University, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Samuel Smith This study explores the complex religious influences shaping Patrick Henry’s belief system. It is common knowledge that he was an Anglican, yet friendly and cooperative with Virginia Presbyterians. However, historians have yet to go beyond those general categories to the specific strains of Presbyterianism and Anglicanism which Henry uniquely harmonized into a unified belief system. Henry displayed a moderate, Latitudinarian, type of Anglicanism. Unlike many other Founders, his experiences with a specific strain of Presbyterianism confirmed and cooperated with these Anglican commitments. His Presbyterian influences could also be described as moderate, and latitudinarian in a more general sense. These religious strains worked to build a distinct religious outlook characterized by a respect for legitimate authority, whether civil, social, or religious. This study goes further to show the relevance of this distinct religious outlook for understanding Henry’s political stances. Henry’s sometimes seemingly erratic political principles cannot be understood in isolation from the wider context of his religious background. Uniquely harmonized -

Chapter 2: What's Fair About Taxes?

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_35 rev0 page 35 2. What’s Fair about Taxes? economists and politicians of all persuasions agree on three points. One, the federal income tax is not sim- ple. Two, the federal income tax is too costly. Three, the federal income tax is not fair. However, economists and politicians do not agree on a fourth point: What does fair mean when it comes to taxes? This disagree- ment explains, in large measure, why it so difficult to find a replacement for the federal income tax that meets the other goals of simplicity and low cost. In recent years, the issue of fairness has come to overwhelm the other two standards used to evaluate tax systems: cost (efficiency) and simplicity. Recall the 1992 presidential campaign. Candidate Bill Clinton preached that those who “benefited unfairly” in the 1980s [the Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced the top tax rate on upper-income taxpayers from 50 percent to 28 percent] should pay their “fair share” in the 1990s. What did he mean by such terms as “benefited unfairly” and should pay their “fair share?” Were the 1985 tax rates fair before they were reduced in 1986? Were the Carter 1980 tax rates even fairer before they were reduced by President Reagan in 1981? Were the Eisenhower tax rates fairer still before President Kennedy initiated their reduction? Were the original rates in the first 1913 federal income tax unfair? Were the high rates that prevailed during World Wars I and II fair? Were Andrew Mellon’s tax Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_36 rev0 page 36 36 The Flat Tax rate cuts unfair? Are the higher tax rates President Clin- ton signed into law in 1993 the hallmark of a fair tax system, or do rates have to rise to the Carter or Eisen- hower levels to be fair? No aspect of federal income tax policy has been more controversial, or caused more misery, than alle- gations that some individuals and income groups don’t pay their fair share. -

Charles Coleman Sellers Collection Circa 1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3

Charles Coleman Sellers Collection Circa 1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3 American Philosophical Society 3/2002 105 South Fifth Street Philadelphia, PA, 19106 215-440-3400 [email protected] Charles Coleman Sellers Collection ca.1940-1978 Mss.Ms.Coll.3 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Background note ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope & content ..........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Indexing Terms ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................10 Series I. Charles Willson Peale Portraits & Miniatures........................................................................10 -

Self-Employment Guide a Resource for SNAP and Cash Programs

Economic Assistance and Employment Supports Division Self-Employment Guide A resource for SNAP and Cash Programs Self-Employment Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ 2 SE 01.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 3 SE 02.0 Definition of a self-employed person ................................................................. 3 SE 03.0 Self-employment ownership types ..................................................................... 3 SE 03.1 Sole Proprietorship ........................................................................................ 3 SE 03.2 Partnership ..................................................................................................... 4 SE 03.3 S Corporations ............................................................................................... 5 SE 03.4 Limited Liability Company (LLC) .................................................................... 6 SE 04.0 Method of Calculation ........................................................................................ 7 SE 05.0 Verifications ....................................................................................................... 7 SE 06.0 Self-employment certification steps ................................................................. 10 SE 07.0 Self-employment Net Income Calculation – 50% Method ............................... -

Chapter 1: Meet the Federal Income

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch1 Mp_1 rev0 page 1 1. Meet the Federal Income Tax The tax code has become near incomprehensible except to specialists. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Chairman, Senate Finance Committee, August 11, 1994 I would repeal the entire Internal Revenue Code and start over. Shirley Peterson, Former Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, August 3, 1994 Tax laws are so complex that mechanical rules have caused some lawyers to lose sight of the fact that their stock-in-trade as lawyers should be sound judgment, not an ability to recall an obscure paragraph and manipulate its language to derive unintended tax benefits. Margaret Milner Richardson, Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, August 10, 1994 It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow. Alexander Hamilton or James Madison, The Federalist, no. 62 the federal income tax is a complete mess. It’s not efficient. It’s not fair. It’s not simple. It’s not compre- hensible. It fosters tax avoidance and cheating. It costs billions of dollars to administer. It costs taxpayers bil- lions of dollars in time spent filling out tax forms and Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch1 Mp_2 rev0 page 2 2 The Flat Tax other forms of compliance. -

Haverford College Bulletin, New Series, 7-8, 1908-1910

STACK. CLASS S ^T^J BOOK 1^ THE LIBRARY OF HAVERFORD COLLEGE (HAVERFORD, pa.) BOUGHT WITH THE LIBRARY FUND BOUND ^ MO. 3 19) V ACCESSION NO. (d-3^50 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/haverfordcollege78have HAVERFORD COLLEGE BULLETIN Vol. VIII Tenth Month, 1909 No. 1 IReports of tbe Boaro of flDanaaers Iprestoent of tbe College ano treasurer of tbe Corporation 1908*1009 Issued Quarterly by Haverford College, Haverford, Pa. Entered December 10, 1902, at Haverford, Pa., as Second Class Matter under the Act of Congress of July 16, 1894 THE CORPORATION OF Haverford College REPORTS OF BOARD OF MANAGERS PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE TREASURER OF THE CORPORATION PRESENTED AT THE ANNUAL MEETING TENTH MONTH 12th, 1909 THE JOHN C. WINSTON COMPANY PHILADELPHIA CORPORATION. President. T. Wistar Brown 235 Chestnut St., Philadelphia Secretary. J. Stogdell Stokes ion Diamond St., Philadelphia Treasurer. Asa S. Wing 409 Chestnut St., Philadelphia BOARD OF MANAGERS. Term Expires 1910. Richard Wood 400 Chestnut St., Phila. John B. Garrett Rosemont, Pa. Howard Comfort 529 Arch St., Phila. Francis Stokes Locust Ave., Germantown, Phila. George Vaux, Jr 404 Girard Building, Phila. Stephen W. Collins 69 Wall St., New York, N. Y. Frederic H. Strawbridge 801 Market St., Phila. J. Henry Scattergood 648 Bourse Building, Phila. Term Expires 1911. Benjamin H. Shoemaker 205 N. Fourth St., Phila. Walter Wood 400 Chestnut St., Phila. William H. Haines 1136 Ridge Ave., Phila. Francis A. White 1221 N. Calvert St., Baltimore, Md. Jonathan Evans "Awbury," Germantown, Phila. -

Ohio Income Tax Update: Changes in How Unemployment Benefits Are Taxed for Tax Year 2020

Ohio Income Tax Update: Changes in how Unemployment Benefits are taxed for Tax Year 2020 On March 31, 2021, Governor DeWine signed into law Sub. S.B. 18, which incorporates recent federal tax changes into Ohio law effective immediately. Specifically, federal tax changes related to unemployment benefits in the federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 will impact some individuals who have already filed or will soon be filing their 2020 Ohio IT 1040 and SD 100 returns (due by May 17, 2021). Ohio taxes unemployment benefits to the extent they are included in federal adjusted gross income (AGI). Due to the ARPA, the IRS is allowing certain taxpayers to deduct up to $10,200 in unemployment benefits. Certain married taxpayers who both received unemployment benefits can each deduct up to $10,200. This deduction is factored into the calculation of a taxpayer’s federal AGI, which is the starting point for Ohio’s income tax computation. Some taxpayers will file their 2020 federal and Ohio income tax returns after the enactment of the unemployment benefits deduction, and thus will receive the benefit of the deduction on their original returns. However, many taxpayers filed their federal and Ohio income tax returns and reported their unemployment benefits prior to the enactment of this deduction. As such, the Department offers the following guidance related to the unemployment benefits deduction for tax year 2020: • Taxpayers who do not qualify for the federal unemployment benefits deduction. o Ohio does not have its own deduction for unemployment benefits. Thus, if taxpayers do not qualify for the federal deduction, then all unemployment benefits included in federal AGI are taxable to Ohio. -

Two Hundred and Twenty -- Five Years 1712 - 1937

Two Hundred and Twenty -- five Years 1712 - 1937 First Presbyterian Church Trenton, ]\Tew Jersey EDWARD ALLE:-; MORRIS, ~vlinister OCTOBER TEXTH TO SEVEXTEEXTH XINETEEN HUXDRED THIRTY-SEVEX OUR PROGRA~I AXD PURPOSE CHRIST whom we preach, warning e,·ery man, and teaching c,·cry man in all wisrlom; that we may present every man perfect in Christ J csus. C o/nssians 1: 2S. TWO HillH)RED AND TWENTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY of the FORMATION OF THE FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF TRENTON, NEW JERSEY OCTOBER 10-17, 1937 THE ANNIVERSARY COMMITTEE General Committee Rev. Edward Alle'!l Morris, Member Ex Officio Mrs. C. Edward Murray, General Chairman Mrs. William E. Green, Vice-Chairman Mr. W. Scott Taylor, Jr., Secretary Mr. Frederick T. Bechtel, Treasurer Mr. Caleb S. Green Mrs. Robert T. Bowman Mrs. Paul L. Cort Mrs. Huston Dixon Mrs. Francis D. Potter Mrs. Horace B. Tobin Mr. Louis S. Rice Mr. Welling G. Titus Mr. Edward S. Wood* Invitation Committee Distinguished Guests :Mrs. Charles Howell Cook Mrs. William E. Green Mrs. William S. Rogers Mrs. D. Wiley Baker Program Committee Mrs. George W. Arnett Rev. Edward Allen Morris Mrs. Bruce Bedford :lfrs. C. Edward Murray Mrs. George E. Reed Mr. Caleb S. Green Museum Committee Publicity Committee Mrs. Joseph L. Bodine Mr. Welling G. Titus Mrs. Francis D. Potter Rev. Kenneth W. Moore :\!rs. William S. Rogers Mr. W. Scott Taylor, Jr. Mrs. Huston Dixon :\Yr. Richard B. Eldridge Mrs. Josiah Harmar Mr. Karl G. Hastedt Social Committee Finance Committee Mrs. Robert T. Bowman Mr. Frederick T. Bechtel :\'!rs. Paul L.