'Constitution': the Great Hall at Manchester University Gothic Architecture Is Synonymous with England's Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey Including Saint

Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church - UNESCO World Heritage Centre This is a cache of http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/426 as retrieved on Tuesday, April 09, 2019. UNESCO English Français Help preserve sites now! Login Join the 118,877 Members News & Events The List About World Heritage Activities Publications Partnerships Resources UNESCO » Culture » World Heritage Centre » The List » World Heritage List B z Search Advanced Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church Description Maps Documents Gallery Video Indicators Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church Westminster Palace, rebuilt from the year 1840 on the site of important medieval remains, is a fine example of neo-Gothic architecture. The site – which also comprises the small medieval Church of Saint Margaret, built in Perpendicular Gothic style, and Westminster Abbey, where all the sovereigns since the 11th century have been crowned – is of great historic and symbolic significance. Description is available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0 English French Arabic Chinese Russian Spanish Japanese Dutch Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) © Tim Schnarr http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/426[04/09/2019 11:20:09 AM] Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including Saint Margaret’s Church - UNESCO World Heritage Centre Outstanding Universal Value Brief synthesis The Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church lie next to the River Thames in the heart of London. With their intricate silhouettes, they have symbolised monarchy, religion and power since Edward the Confessor built his palace and church on Thorney Island in the 11th century AD. -

Westminster Abbey a Service for the New Parliament

St Margaret’s Church Westminster Abbey A Service for the New Parliament Wednesday 8th January 2020 9.30 am The whole of the church is served by a hearing loop. Users should turn the hearing aid to the setting marked T. Members of the congregation are kindly requested to refrain from using private cameras, video, or sound recording equipment. Please ensure that mobile telephones and other electronic devices are switched off. The service is conducted by The Very Reverend Dr David Hoyle, Dean of Westminster. The service is sung by the Choir of St Margaret’s Church, conducted by Greg Morris, Director of Music. The organ is played by Matthew Jorysz, Assistant Organist, Westminster Abbey. The organist plays: Meditation on Brother James’s Air Harold Darke (1888–1976) Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’ BWV 678 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) The Lord Speaker is received at the East Door. All stand as he is conducted to his seat, and then sit. The Speaker of the House of Commons is received at the East Door. All stand as he is conducted to his seat, and then sit. 2 O R D E R O F S E R V I C E All stand to sing THE HYMN E thou my vision, O Lord of my heart, B be all else but naught to me, save that thou art, be thou my best thought in the day and the night, both waking and sleeping, thy presence my light. Be thou my wisdom, be thou my true word, be thou ever with me, and I with thee, Lord; be thou my great Father, and I thy true son, be thou in me dwelling, and I with thee one. -

Introduction the Whitworth Has Been Making Art Useful Since 1889

Introduction The Whitworth has been making art useful since 1889. The gallery was originally founded with the wealth of Stockport-born engineer Sir Joseph Whitworth (1803-87). He transformed engineering through the introduction of a standardised system of measurement for machine parts. Whitworth left no formal instructions about how the bulk of his fortune (equivalent to more than £130 million today) should be used after his death. This decision was left to his widow Lady Mary Louisa and his good friends and fellow philanthropists Robert Darbishire and Richard Copley Christie. For the very first time examples of Joseph Whitworth’s world-changing mechanical innovations are on display amongst highlights from the gallery’s diverse collections of textiles, fine art and wallpaper. Whitworth’s commitment to standardisation is used throughout the exhibition as a counterpoint to significant moments of deviation within the gallery’s collection and history. This exhibition explores the establishment of the Whitworth. The founding intention to create a forward-thinking art and design collection is interrogated and its difficult histories exposed. Gender, labour, race and class inequalities are just some of the issues being confronted. This has informed our conversations about the history of the gallery and its collections and we continue to actively engage in this work. Art and Industry William Morris described the exhibits inside the Great Exhibition of 1851 as ‘wonderfully ugly’. For Morris and the art critic John Ruskin, this celebration of global arts highlighted how mass production had led to a separation between English workers and making. Both men were prominent in the Arts and Crafts movement, which aimed to promote hand-making over mass production and advocate the decorative arts. -

The Prerogative and Environmental Control of London Building in the Early Seventeenth Century: the Lost Opportunity

The Prerogative and Environmental Control of London Building in the Early Seventeenth Century: The Lost Opportunity Thomas G. Barnes* "What experience and history teach is this-that people and governments never have learned anything from history or or acted on principles deducted from it." Undaunted by Hegel's pessimism, Professor Barnes demonstrates that our current concern for the environment is not as new as we might suppose. The most considerable, continuous, and best docu- mented experiment in environmental control in the Common Law tradition was conducted before the middle of the seventeenth century. An almost accidental circumstance determined that this experiment would become a lost opportunity. Now if great Cities are naturally apt to remove their Seats, I ask which way? I say, in the case of London, it must be West- ward, because the Windes blowing near . [three-fourths] of the year from the West, the dwellings of the West end are so much the more free from the fumes, steams, and stinks of the whole Easterly Pyle; which where Seacoal is burnt is a great matter. Now if [it] follow from hence, that the Pallaces of the greatest men will remove Westward, it will also naturally fol- low, that the dwellings of others who depend upon them will creep after them. This we see in London, where the Noble- mens ancient houses are now become Halls for Companies, or turned into Tenements, and all the Pallaces are gotten West- ward; Insomuch, as I do not doubt but that five hundred years hence, the King's Pallace will be near Chelsey, and the old building of Whitehall converted to uses more answerable to their quality, . -

The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Transcript

The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Transcript Date: Thursday, 11 February 2010 - 12:00AM Location: Museum of London The Politics of Architecture in Tudor and Stuart London Professor Simon Thurley Visiting Gresham Professor of the Built Environment 11/12/2010 Tonight, and again on the 11 March, I will be looking at the interrelation of architecture and power. The power of kings and the power of government and how that power has affected London. On the 11th I will be looking at Victorian and Edwardian London but tonight I'm going to concentrate on the sixteenth and seventeenth century and show how Tudor and Stuart Monarchs used, with varying degrees of success, the great buildings of the City of London to bolster their power. The story of royal buildings in the City starts with the Saxons. Before 1052 English Kings had had a palace in London at Aldermanbury, but principally to avoid the instability, turbulence and violence of the populace Edward the Confessor, the penultimate English King, had moved his royal palace one and a half miles west to an Island called Thorney. On Thorney Island the Confessor built the great royal abbey and palace of Westminster. And it was here, that William the Conqueror chose to be crowned on Christmas day 1066, safely away from the still hostile inhabitants of the city. London was too big, powerful and independent to be much influenced by the Norman Conquest. Business continued unabated under a deal done between the city rulers and their new king. However William left a major legacy by establishing the metropolitan geography of the English monarchy - the subject of my talk this evening. -

Persons Index

Architectural History Vol. 1-46 INDEX OF PERSONS Note: A list of architects and others known to have used Coade stone is included in 28 91-2n.2. Membership of this list is indicated below by [c] following the name and profession. A list of architects working in Leeds between 1800 & 1850 is included in 38 188; these architects are marked by [L]. A table of architects attending meetings in 1834 to establish the Institute of British Architects appears on 39 79: these architects are marked by [I]. A list of honorary & corresponding members of the IBA is given on 39 100-01; these members are marked by [H]. A list of published country-house inventories between 1488 & 1644 is given in 41 24-8; owners, testators &c are marked below with [inv] and are listed separately in the Index of Topics. A Aalto, Alvar (architect), 39 189, 192; Turku, Turun Sanomat, 39 126 Abadie, Paul (architect & vandal), 46 195, 224n.64; Angoulême, cath. (rest.), 46 223nn.61-2, Hôtel de Ville, 46 223n.61-2, St Pierre (rest.), 46 224n.63; Cahors cath (rest.), 46 224n.63; Périgueux, St Front (rest.), 46 192, 198, 224n.64 Abbey, Edwin (painter), 34 208 Abbott, John I (stuccoist), 41 49 Abbott, John II (stuccoist): ‘The Sources of John Abbott’s Pattern Book’ (Bath), 41 49-66* Abdallah, Emir of Transjordan, 43 289 Abell, Thornton (architect), 33 173 Abercorn, 8th Earl of (of Duddingston), 29 181; Lady (of Cavendish Sq, London), 37 72 Abercrombie, Sir Patrick (town planner & teacher), 24 104-5, 30 156, 34 209, 46 284, 286-8; professor of town planning, Univ. -

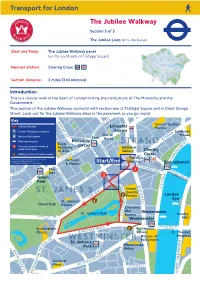

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

A History of the University of Manchester Since 1951

Pullan2004jkt 10/2/03 2:43 PM Page 1 University ofManchester A history ofthe HIS IS THE SECOND VOLUME of a history of the University of Manchester since 1951. It spans seventeen critical years in T which public funding was contracting, student grants were diminishing, instructions from the government and the University Grants Commission were multiplying, and universities feared for their reputation in the public eye. It provides a frank account of the University’s struggle against these difficulties and its efforts to prove the value of university education to society and the economy. This volume describes and analyses not only academic developments and changes in the structure and finances of the University, but the opinions and social and political lives of the staff and their students as well. It also examines the controversies of the 1970s and 1980s over such issues as feminism, free speech, ethical investment, academic freedom and the quest for efficient management. The author draws on official records, staff and student newspapers, and personal interviews with people who experienced the University in very 1973–90 different ways. With its wide range of academic interests and large student population, the University of Manchester was the biggest unitary university in the country, and its history illustrates the problems faced by almost all British universities. The book will appeal to past and present staff of the University and its alumni, and to anyone interested in the debates surrounding higher with MicheleAbendstern Brian Pullan education in the late twentieth century. A history of the University of Manchester 1951–73 by Brian Pullan with Michele Abendstern is also available from Manchester University Press. -

St Thomas Becket and London, but Some Background Information May Be Helpful

25 February 2020 Thomas Becket and London Professor Caroline barron Introduction This lecture is about St Thomas Becket and London, but some background information may be helpful. Thomas Becket was born in London in 1120, the son of Gilbert and Mathilda Becket whose families had come from Rouen in the wake of the Norman Conquest. Gilbert Becket was a rich and successful Londoner who seems to have made his money by owning and dealing in property. He lived in the small central parish of St Mary Colechurch on the north side of Cheapside. As yet there were no elected mayors of London (this privilege came by a royal charter in May 1215), but the city was allowed to elect its own sheriffs and Gilbert seems to have held this office in the 1130s. The Becket family fortunes were seriously affected by a fire (there were many such fires in early medieval London) which destroyed much of Gilbert’s property. In about 1140 young Thomas entered the employment of the sheriff, Osbert Huitdeniers (Eightpence) and became, in effect, a civil servant. He must have had a good education, possibly in one of the schools which we know existed in London at this time. From acting as a clerk to the sheriff, Thomas moved in 1143 to join the prestigious household of Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury (1138-1161). Although in minor clerical orders, Thomas enjoyed the ‘extravagant and ostentatious’ lifestyle of a successful young courtier and he attracted the attention of the king, Henry II who appointed him as his chancellor in 1155. -

Figure 1. Sharpshooter Weapons in the American Civil War (Photo Ex

ASAC_Vol107_02-Carlson_130003.qxd 8/23/13 7:58 PM Page 2 Figure 1. Sharpshooter Weapons in the American Civil War (photo ex. author's collection). 107/2 Reprinted from the American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin 107:2-28 Additional articles available at http://americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/resources/articles/ ASAC_Vol107_02-Carlson_130003.qxd 8/23/13 7:58 PM Page 3 Sharpshooter Weapons in the American Civil War By Bob Carlson There is a proud tradition of sharpshooting in the mili- tary history of our nation (Figure 1). From the defeat of General Edward Braddock and the use of flank companies of riflemen in the French and Indian War, to the use of long rifles against Ferguson and the death of General Simon Fraser in the Revolutionary War at Saratoga, to the War of 1812 when British General Robert Ross was shot on the way to take Baltimore in 1814 and when long rifles were instru- mental at New Orleans in January 1815, up to the modern wars with the use of such arms as the Accuracy International AX338 sniper rifle, sharpshooters have been crucial in the outcome of battles and campaigns. I wish to dedicate this discussion to a true American patriot, Chris Kyle, a much decorated Navy Seal sniper whom we lost in February of this year, having earned two silver and four bronze stars in four tours of service to his country. He stated that he killed the enemy to save the lives of his comrades and his only regret was those that he could not save. He also aided his fellow attackers at bay; harassing target officers and artillerymen disabled veterans for whom he worked tirelessly with his from a long-range; instilling psychological fear and feelings Heroes Project after returning home. -

Industrial Biography

Industrial Biography Samuel Smiles Industrial Biography Table of Contents Industrial Biography.................................................................................................................................................1 Samuel Smiles................................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. IRON AND CIVILIZATION..................................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. EARLY ENGLISH IRON MANUFACTURE....................................................................16 CHAPTER III. IRON−SMELTING BY PIT−COAL−−DUD DUDLEY...................................................24 CHAPTER IV. ANDREW YARRANTON.................................................................................................33 CHAPTER V. COALBROOKDALE IRON WORKS−−THE DARBYS AND REYNOLDSES..............42 CHAPTER VI. INVENTION OF CAST STEEL−−BENJAMIN HUNTSMAN........................................53 CHAPTER VII. THE INVENTIONS OF HENRY CORT.........................................................................60 CHAPTER VIII. THE SCOTCH IRON MANUFACTURE − Dr. ROEBUCK DAVID MUSHET..........69 CHAPTER IX. INVENTION OF THE HOT BLAST−−JAMES BEAUMONT NEILSON......................76 CHAPTER X. MECHANICAL INVENTIONS AND INVENTORS........................................................82 -

A History of the University of Manchester Since 1951

Pullan2004jkt 10/2/03 2:43 PM Page 1 University ofManchester A history ofthe HIS IS THE SECOND VOLUME of a history of the University of Manchester since 1951. It spans seventeen critical years in T which public funding was contracting, student grants were diminishing, instructions from the government and the University Grants Commission were multiplying, and universities feared for their reputation in the public eye. It provides a frank account of the University’s struggle against these difficulties and its efforts to prove the value of university education to society and the economy. This volume describes and analyses not only academic developments and changes in the structure and finances of the University, but the opinions and social and political lives of the staff and their students as well. It also examines the controversies of the 1970s and 1980s over such issues as feminism, free speech, ethical investment, academic freedom and the quest for efficient management. The author draws on official records, staff and student newspapers, and personal interviews with people who experienced the University in very 1973–90 different ways. With its wide range of academic interests and large student population, the University of Manchester was the biggest unitary university in the country, and its history illustrates the problems faced by almost all British universities. The book will appeal to past and present staff of the University and its alumni, and to anyone interested in the debates surrounding higher with MicheleAbendstern Brian Pullan education in the late twentieth century. A history of the University of Manchester 1951–73 by Brian Pullan with Michele Abendstern is also available from Manchester University Press.