The David Nicholls Memorial Lectures No.2 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2011 No.201, Free to Members, Quarterly

THE BRIXTON SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Spring issue, April 2011 No.201, free to members, quarterly. Registered with the London Forum of Amenity Societies, Registered Charity No.1058103, Website: www.brixtonsociety.org.uk Our next open meeting Thursday 9th June: Annual General Meeting 7 pm at the Vida Walsh Centre, Windmill re-opening 2b Saltoun Road, SW2 A year ago, our newsletter reported that the Time again to report on what we have been Heritage Lottery Fund had agreed to support doing over the past year, collect ideas for the the restoration of the mill. Since then it’s made year ahead, and elect committee members to the front cover of Local History magazine, as carry them out. Agenda details from the above. Now the Friends of Windmill Gardens Secretary, Alan Piper on (020) 7207 0347 or present a series of events, with guided tours by e-mail to [email protected] inside the mill offered on each date. Open Garden Squares May Day Launch Parade, 2nd May: A theatrical parade starts from Windrush Weekend - 11 & 12 June Square at 2 pm and proceeds to the mill This year we plan to host two events on for its official re-opening. Ends 4-30 pm. Windrush Square: On Saturday our theme is Growing in Brixton with stalls Open Day, Sunday 12 June: selling plants and promoting green ideas. Windmill open 2 pm to 4 pm. On Sunday we switch to Art in Brixton, showing the work of local artists and Windmill Festival, Sunday 10 July: encouraging you to have a go yourself. -

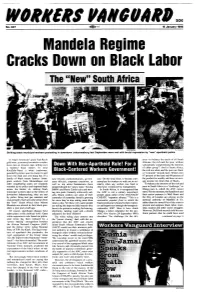

Workers Vanguard Interview Party of EW

50¢ ~)(.62J No. 637 ~~' 19 January 1996 Mandela Regime Cracks Down on Black Labor Striking black municipal workers protesting In downtown Johannesburg last September were met with brutal repression by "new" apartheid police. In Anglo American's giant Vaal Reefs anee-to halanee the needs of all South gold mine, a runaway locomotive crashes Af~icans, the rich and the poor, without down into an eievator cage, killing over suhstantially compromising the interests a hundred black miners. In rural of either group"! And in South Africa, K waZulu-Natal, a white landowner, the rich are white and the poor are black guarded by police, uses his tractor to pull or "coloured" (mixed-race). Whites own down the mud and cow-dung hut of a 87 percent of the land and 90 percent of family of black tenant farmers. Immi now become parliamentarians, govern tory. On the shop floor, it became com the productive wealth, and have an aver grant workers from Mozambique and ment officials, corporate executives, as monplace for workers to walk out in sol age income ten times that of hlacks. other neighboring states are routinely well as top union bureaucrats-have idarity when any worker was fired or To balance the interests of the rich and rounded up by police and deported back jumped aboard the "gravy train," buying otherwise victimized by management. poor in South Africa is a "challenge," as across the border. As striking black BMWs and Pierre Cardin suits and mov In South Africa, it is recognized that' Manga puts it, which the ANC cannot municipal workers take to the streets of ing into posh, formerly white-only sub the ANC is not a unitary movement; meet. -

Pioneers & Champions

WINDRUSH PIONEERS & CHAMPIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS WINDRUSH PIONEERS Windrush Foundation is very grateful for the contributions Preface 4 David Dabydeen, Professor 82 to this publication of the following individuals: Aldwyn Roberts (Lord Kitchener) 8 David Lammy MP 84 Alford Gardner 10 David Pitt, Lord 86 Dr Angelina Osborne Allan Charles Wilmot 12 Diana Abbott MP 88 Constance Winifred Mark 14 Doreen Lawrence OBE, Baroness 90 Angela Cobbinah Cecil Holness 16 Edna Chavannes 92 Cyril Ewart Lionel Grant 18 Floella Benjamin OBE, Baroness 94 Arthur Torrington Edwin Ho 20 Geoff Palmer OBE, Professor Sir 96 Mervyn Weir Emanuel Alexis Elden 22 Heidi Safia Mirza, Professor 98 Euton Christian 24 Herman Ouseley, Lord 100 Marge Lowhar Gladstone Gardner 26 James Berry OBE 102 Harold Phillips (Lord Woodbine) 28 Jessica Huntley & Eric Huntley 104 Roxanne Gleave Harold Sinson 30 Jocelyn Barrow DBE, Dame 106 David Gleave Harold Wilmot 32 John Agard 108 John Dinsdale Hazel 34 John LaRose 110 Michael Williams John Richards 36 Len Garrison 112 Laurent Lloyd Phillpotts 38 Lenny Henry CBE, Sir 114 Bill Hern Mona Baptiste 40 Linton Kwesi Johnson 116 42 Cindy Soso Nadia Evadne Cattouse Mike Phillips OBE 118 Norma Best 44 Neville Lawrence OBE 120 Dione McDonald Oswald Denniston 46 Patricia Scotland QC, Baroness 122 Rudolph Alphonso Collins 48 Paul Gilroy, Professor 124 Verona Feurtado Samuel Beaver King MBE 50 Ron Ramdin, Dr 126 Thomas Montique Douce 52 Rosalind Howells OBE, Baroness 128 Vincent Albert Reid 54 Rudolph Walker OBE 130 Wilmoth George Brown 56 -

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Annual Report 1998

Ministry of Foreign Affairs "Service within and beyond our borders" I Annual Report 1998 .. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Mission Statement .................... .. ............. ... .. ..... ....................... .............. .............. 3 Executive Summary ... ........... .. .... ..... ............. ............................... ........... ............... 4 Department of Americas and Asia ....................... ...... ....... .................................... 7 Economic Affairs Department .......... ...................................... .. ......... .. .. .. ........... 14 Multilateral and Global Affairs Department .............. .. .. ......... ..... .............. ... .......... 32 Minister's Secretariat ......... .............................................. .. ....... ... ................. .. .... 51 Public Affairs and Information Unit ................. ....... ... ....... ... ....... .. ................... ...... 58 Administration and Finance Department .................. ...... ............ ................. .... .. .. 60 Protocol and Consular Affairs Department ......... ............ .............. ......... .. ............ 63 Guyana Embassy- Beijing ... ............... ..................................... ; .... .... .................. 67 Guyana Embassy - Brasilia ...... ........................................................................... 7 4 Guyana Embassy- Brussels ......................................... .. '. ........... ... .. ... .......... ....... 90 Guyana Embassy - Caracas ........................................... -

O "A Well-Oiled Nazi Machine": an Analysis of the Growth of the Extreme Right in Britain

A o "A well-oiled Nazi machine": an analysis of the growth of the extreme right in Britain. Birmingham, AF and R Publications, c. 1974, 32 RSWG o [Coard, Bernard], Education and the West Indian Child - a criticism of the ESN School System. Paper, undated, 32 JKhnr.cg o Adams, Caroline, "They Sell Cheaper and They Live Very Odd". London, Community and Race Relations Unit of the British Council of Churches, 1976, 32 HKhkb o Adams, FJ, Problems of the education of Immigrants from the standpoint of the Local Education Authority. Background paper for the IRR/RAI/BSA Third Annual Race relations Conference "Incipient Ghettoes and the Concentration of Minorities", London, c. 1970, 32 JK hok.cg o AFFOR, Talking Blues: the Black community speaks about its relationship with the police. Birmingham, AFFOR, 1978 o Afro-West Indian Union, Don't Blame the Blacks. Basford, Nottingham, undated, 32 HKhdk o Alavi, Hamsa et al., Immigration. London, NCLC Publishing Society, Plebs Vol. 57 no. 12, 1965, 32 HABQYI o Ali, Arif (ed.), Third World Impact (formally Westindians in Britain), London, Hansib Publications, 1982, 32.HKhdk.qr o All Lambeth Anti-Racist Movement, A Cause for Alarm: a study of policing in Lambeth. London, Blackrose Press, c1980, 32.JST o Allegations of police harassment of and brutality towards certain West Indians and the alleged sanctioning of one such instance of brutality by a senior police officer of the Leicester police. Mimeographed document, c. 1970, 32 JR.HT o Allen, Sheila and Joanna Bornat, Unions and Immigrant Workers: how they see each other. -

The Other Windrush

The Other Windrush ‘This illuminating, vivid volume is a fitting tribute to the experiences of migration, struggle and celebration that shaped those communities born out of the system of Caribbean indenture.’ —Hanif Kureishi, author of The Buddha of Suburbia ‘Through moving and insightful stories and testimonies, the legacies of indenture are powerfully inscribed.’ —Hannah Lowe, author of Long Time No See ‘This kaleidoscopic survey illuminates corners of modern Britain that have been overlooked. Filed with vivid stories about the Chinese and Indian contribution to Caribbean culture, it is also a vibrant history of immigration to the UK: a colourful work in every sense.’ —Sibghat Kadri QC ‘I cried when I read this beautifully furious book on the life, loves and heroic struggles of my brave ancestors, the unfree indentured Indian and Chinese men and women who have been consciously and cruelly written out of British and Caribbean history.’ —Heidi Safia Mirza, Professor of Race, Faith and Culture at Goldsmiths, University of London The Other Windrush Legacies of Indenture in Britain’s Caribbean Empire Edited by Maria del Pilar Kaladeen and David Dabydeen First published 2021 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Maria del Pilar Kaladeen and David Dabydeen 2021 The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The editors are grateful to the Ameena Gafoor Institute for the Study of Indentureship and Its Legacies for supporting the publication of this book. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 4355 6 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 4354 9 Paperback ISBN 978 0 7453 4358 7 PDF ISBN 978 0 7453 4356 3 EPUB ISBN 978 0 7453 4357 0 Kindle Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Contents List of figures vii Introduction: ‘My Father’s Journey Made Me Who I Am’ 1 Maria del Pilar Kaladeen and David Dabydeen 1. -

A Question of Leadership

a question of leadership. LordPhotos: René Carayol Herman Lord Herman Ouseley RENÉ CARAYOL, u|Chief’s leadership guru, goes head-to-head with an African leader every month. Ouseley Lord ouseley was born in guyana in 1945 and came to england when he was 11. He became chief exec- utive of the london borough of lambeth and the former inner london education authority (the first black person to hold such an office). In 1993, he became the executive chairman of the commission for racial equality, a position he held until 2000. In 2001, he was raised to the peerage of baron ouseley of peckham rye in southwark. Herman ouseley is also the chair of chandran foundation, kick-it-out plc (let’s kick racism out of football campaign), policy research institute on ageing & just how much he was to shape my determination to change ethnicity (university of central england). the world around us. Not everything he said or did was per- fect. I soon learned to be discerning about what to take on Which contemporary leaders do you admire? board. I now have the privilege of mentoring many people, Tony Ottey, a Jamaican national, an inspirational leader and I love doing it as I learn much from my mentees, maybe amongst young people. He inspired them to become educated. more than they ever learn from me. He said provocative things where most others hesitated. To mixed audiences of different races he would challenge all, “we What do you believe is the most important driver for are definitely in the same boat, but on different decks”. -

Copyright by Mohan Ambikaipaker 2011

Copyright by Mohan Ambikaipaker 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Mohan Ambikaipaker certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: GROUNDINGS IN ANTI-RACISM: RACIST VIOLENCE AND THE ‘WAR-ON-TERROR’ IN EAST LONDON Committee: João H. Costa Vargas, Supervisor Sharmila Rudrappa Edmund T. Gordon Douglass E. Foley Benjamin Carrington GROUNDINGS IN ANTI-RACISM: RACIST VIOLENCE AND THE ‘WAR-ON-TERROR’ IN EAST LONDON by Mohan Ambikaipaker, BA; MA Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication Ambikaipaker Arunasalam, 1937-2008 In remembrance of your love and your legacy of courageous struggle and for Mallika Isabel Mohan, born February 7, 2009 our future Acknowledgements I would like to express a deep appreciation to the many institutions, people and overlapping communities that have made this work possible. This project could not have been undertaken without the Wenner-Gren Foundation award of a dissertation fieldwork grant and a University Continuing Fellowship that supported writing. The John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies has supported my work through the award of multiple research grants and fellowships both prior to and after fieldwork, and most importantly it has provided the rare space where race, racism and the African diaspora could be rigorously thought about and debated intellectually at the University of Texas, Austin. The Center for Asian American Studies has funded my last years in graduate school and enabled me to develop my own courses on Black and Asian social movements and to create self-defined people of color intellectual spaces. -

Windrush Pioneers & Champions Booklet

WINDRUSH PIONEERS & CHAMPIONS 70 WINDRUSH PIONEERS & CHAMPIONS © Windrush Foundation 2018 WINDRUSH The rights of Windrush Foundation are identified to be the Authors and have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. FOUNDATION All Rights Reserved Windrush Foundation is a registered charity that designs and delivers heritage No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by photocopying or by any electronic or projects, programmes and initiatives which highlight the African and other means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without the permission in Caribbean contributions to World War II, to the arts, public services, commerce writing of the copyright owner / publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding and other areas of socio-economic and cultural life in Britain and the or cover other than that in which it is published. Commonwealth. The London-based organisation was established in 1996 ISBN 978-0-9562506-3-6 to promote good race and community relations, build cohesion, eliminate discrimination and encourage equality of opportunity for all – placing particular emphasis on addressing issues of ‘race’/’ethnicity’, equalities and cultural Disclaimer: diversity. The organisation has a successful track-record for delivering The publishers have made every effort to include a credit alongside each image. If a rightful both local community-based projects and high-profile national learning owner identifies any of the images herein, please notify Windrush Foundation immediately. and participation activities for diverse audiences – including lectures/talks, multi-media presentations, group discussions, poetry, music, and other Book & cover design by Mervyn Weir performing arts events featuring inter-cultural and Diasporic aspects of First Published in December 2018 by WINDRUSH FOUNDATION African, Caribbean and black British histories and heritage for children and young people, families and life-long learners. -

Coronavirus and Race Attacks: Racial Violence and Racial Terror in Britain

Coronavirus and Race Attacks: Racial Violence and Racial Terror in Britain “In our own time, the steady erosion of the inherited privileges of race has destabalised western identities and institutions – and it has unveiled racism as an enduringly potent political force, empowering volatile demagogues in the heart of the modern west...Today, as white supremecists feverishly build transnational alliances, it becomes imperative to ask, as Dubois did in 1910: 'What is whiteness that one should so desire it?”.i This paper explores the enduring phenomenon of racial violence against Blackii people in the White western world in general and in the United Kingdom in particular. This engages the historical antecedents of violence against Black people and the convergence of social phenomena such as race, class and gender in the everyday lived experiences of ordinary, everyday Black people. Our exploration begins its focus on the current racial violence, engendered by the coronavirus pandemic, which has dramatically increased in Britain and the White western world. We place this phenomenon within the broader context of racial terrorism and racist harassment and attacks against Black people, which have been historically endemic to British society, and the wider western world in general. In our review, we see that current manifestation of racial violence is in fact a continuation of over 500 years of racial oppression and violence which has been central to concepts of White identity. We see that the coronavirus inspired violence is but the tip of the iceberg of a deep enduring legacy of violence against Black people and crucially, a crisis and fracture in foundation of the mirage of a multinational non-racial society. -

Hansib Catalogue

HANSIB PUBLICATIONS MULTICULTURAL PUBLISHING SINCE 1970 www.hansibpublications.com CATALOGUE • WINTER 2014-2015 UK/EU Distributor & Overseas distributors, agents, stockists, wholesalers and bookshops UNITED KINGDOM & EUROPE GUYANA SAINT LUCIA Austin’s Book Services AF Valmont Turnaround Publisher Services Ltd 190 Church Street, Georgetown 1-7 Laborie Street, P.O. Box 172, Castries Unit 3, Olympia Trading Estate Tel: 592 226 7350 Tel: 758 452 3817. Fax: 758 452 4225 Coburg Road, London N22 6TZ Fax: 592 227 7396 Email: [email protected] Tel: 0208 829 3000. Fax: 0208 881 5088 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Sunshine Bookshop Michael Forde Bookshop BOX GM 565, Gablewoods Mall, Castries 41 Robb Street, Lacytown, Georgetown Tel: 758 452 3222. Fax: 758 453 1879 ANGUILLA Tel: 592 225 5326 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Coral Reef Bookstore TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Little Harbour New Era Business Enterprise Books & Office Supplies P.O. Box 966 Cheddi Jagan International Airport THL Building, Milford Road, Scarborough The Valley A1-2640 Tel: 592 261 4354 Tel: 868 635 2665 Tel: 264-462 6657 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] JAMAICA Charran Bookstore ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA Trinity Mall, Trinity Headstart Bookshop Tel: 868 640 3155 Best of Books 75 East Street, Kingston Email: [email protected] Lower St Mary’s Street, P.O. Box 433 Tel: 876 948 2617 / 967 3086 St John’s Gurley & Associates (The Book Specialist) Tel: 268 562 3198. Fax: 268 462 2199 Island Books & Beyond Ltd 35 Richmond Street, Port of Spain Email: [email protected] 1901 Morgan Road, Ironshore, Montego Bay Tel: 868 623 3461. -

Black Letter Law 2012.Indb

BLACK LETTER LAW | 2012 SHOWCASING ACHIEVEMENT IN LAW DEBO NWAUZU I N ASSOCIATION WITH SEVENTH EDITION £25.00 2 This book is dedicated to all our children, our tomorrow Debo Nwauzu 3 CREDITS COVER From left to right: Top row: David Lammy MP, Ali Naseem Bajwa QC, Amol Prabhu, Annette Byron, Tim Proctor, Aziz Rahman and Michael Webster. Second row: Alicia Foo, Boma Ozobia, Chirag Karia QC, Constance Briscoe, Daniel Alexander QC, David Carter and Alain Choo Choy QC. Third Row: Sir Desmond de Silva QC, Doreen Forrester-Brown, Elizabeth Uwaifo, Fiona Bolton, George Lubega, Grace Ononiwu OBE and Yetunde Dania. Fourth Row: Harold Brako and Abid Mahmood. Fifth Row: Helen Grant MP and Jane Cheong Tung Sing. Sixth Row: Makbool Javaid, John Adebiyi, Judy Khan QC, Keith Vaz MP, Kultar Khangura, Leslie Thomas and Jawaharlal Nehru. Seventh Row: Martin Forde QC, Bayo Odubeko, Moni Mannings, Nwabueze Nwokolo, Oba Nsugbe QC, Professor Andrew Choo and Professor Nelson Enonchong. Eighth Row: Satinder Hunjan QC, Saimo Chahal, Samallie Kiyingi, Sanjeev Dhuna, Sarah Wiggins, Sarah Lee and Pushpinder Saini QC. Ninth Row: Shaheed Fatima, Shaun Wallace, Sophie Chandauka, Sunil Gadhia, Sunil Sheth, Sunny Mann and Anesta Weekes QC. Bottom Row: Habib Motani and Anna Gardner. First published in Great Britain in 2012 by: Totally Management Ltd, 288 Bishopsgate, London, EC2M 4QP Email [email protected] www.onlinebld.com ©Debo Nwauzu Author and Publisher: Debo Nwauzu Sub-Editor and Researcher: Shelagh Meredith Designed by: Design Tribe Printed and bounded in the UK by: Printondemand-worldwide © Copyright No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying in the UK by the Copyright Licensing Agency.