Parallel-Text Comparison of Wordsworth's Five Editions of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

SPRINGFIELD FELLWALKING CLUB 6Th JULY 2019 – 7Th DEC 2019

SPRINGFIELD FELLWALKING CLUB 6th JULY 2019 – 7th DEC 2019 WALK NO WALK DATE VENUE 1242 06/07/19 GLENRIDDING 1243 20/07/19 MALHAM 1244 03/08/19 BASSENTHWAITE 1245 17/08/19 HEBDEN BRIDGE - HAWORTH 1246 31/08/19 N.D.G. HOTEL - GRASMERE 1247 14/09/19 LOGGERHEADS ( no pub stop ) 1248 28/09/19 BROUGHTON - IN - FURNESS 1249 12/10/19 GRASMERE 1250 26/10/19 HOLLINGWORTH LAKE 1251 09/11/19 TROUTBECK 1252 23/11/19 HAWKSHEAD 1253 07/12/19 CLAPHAM www.springfieldfellwalking.co.uk PICK UP POINTS A CHANGE OF CLOTHING MUST BE LEFT ON THE COACH. ONE MEAL AND DRINKS TO BE CARRIED. EMERGENCIES ; DIAL 999 ASK FOR MOUNTAIN RESCUE PICK UP POINT TIME BISPHAM RD. ROUNDABOUT 7-30 PLYMOUTH RD. ROUNDABOUT 7-36 NEWTON DRIVE ROUNDABOUT 7-40 PRESTON NEW RD. 7-49 ( Macdonalds ) PADDOCK DRIVE 7-50 KIRKHAM SQUARE 7-57 CARR HILL RD. 7-59 BELL & BOTTLE 8-02 CLIFTON VILLAGE ( 1st bus stop on entering village ) 8-05 LEA POST OFFICE/LEA CLUB 8-13 CLIFTON AVE. 8-15 LANE ENDS ( Bus shelter ) 8-19 BLACK BULL FULWOOD 8-23 ROUTE Start – Bispham Roundabout – A587 – Preston New Road – Kirkham – Clifton Village – Lea – Ashton – Black Bull Fulwood WALK NO WALK DATE VENUE 1242 06/07/19 GLENRIDDING MAP ; EXPLORER OL 5 ENGLISH LAKES N E AREA ‘A’ – COW BRIDGE – GALE CRAG – HARTSOP ABOVE HOW – HART CRAG – FAIRFIELD – COFFA PIKE – DEEPDALE HAUSE – ST SUNDAY CRAG – THORN HOW - LANTY’S TARN – GLENRIDDING LEADER 9.1/2 MLS ; 3600’ TL. ASC. ‘B’ – PATTERDALE – BOREDALE HAUSE – PLACE FELL – MORTAR CRAG – LOW MOSS – SCALEHOW WOOD – SILVER BAY – SIDE FARM – GRISEDALE BRIDGE – GLENRIDDING LEADER 8.1/2 MLS ; 2400’ TL. -

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - the Check List Thirty-Six Circular Walks Covering All the Peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - The Check List Thirty-six circular walks covering all the peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells. This list is provided for those of you wishing to complete the Wainwright's in 36 walks. Simply tick off each mountain as completed when the task of climbing it has been accomplished. Mountain Book Walk Completed Arnison Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birkhouse Moor The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birks The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Catstye Cam The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Clough Head The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Dollywaggon Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Dove Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Fairfield The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Glenridding Dodd The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Gowbarrow Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Dodd The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Great Mell Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Rigg The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Side The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Hartsop Above How The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit Helvellyn The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Heron Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Mountain Book Walk Completed High Hartsop Dodd The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit High Pike (Scandale) The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Little Hart Crag -

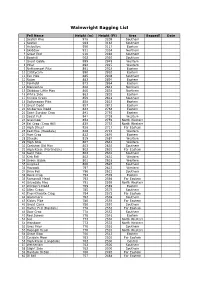

Wainwright Bagging List

Wainwright Bagging List Fell Name Height (m) Height (Ft) Area Bagged? Date 1 Scafell Pike 978 3209 Southern 2 Scafell 964 3163 Southern 3 Helvellyn 950 3117 Eastern 4 Skiddaw 931 3054 Northern 5 Great End 910 2986 Southern 6 Bowfell 902 2959 Southern 7 Great Gable 899 2949 Western 8 Pillar 892 2927 Western 9 Nethermost Pike 891 2923 Eastern 10 Catstycam 890 2920 Eastern 11 Esk Pike 885 2904 Southern 12 Raise 883 2897 Eastern 13 Fairfield 873 2864 Eastern 14 Blencathra 868 2848 Northern 15 Skiddaw Little Man 865 2838 Northern 16 White Side 863 2832 Eastern 17 Crinkle Crags 859 2818 Southern 18 Dollywagon Pike 858 2815 Eastern 19 Great Dodd 857 2812 Eastern 20 Stybarrow Dodd 843 2766 Eastern 21 Saint Sunday Crag 841 2759 Eastern 22 Scoat Fell 841 2759 Western 23 Grasmoor 852 2759 North Western 24 Eel Crag (Crag Hill) 839 2753 North Western 25 High Street 828 2717 Far Eastern 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 2710 Western 27 Hart Crag 822 2697 Eastern 28 Steeple 819 2687 Western 29 High Stile 807 2648 Western 30 Coniston Old Man 803 2635 Southern 31 High Raise (Martindale) 802 2631 Far Eastern 32 Swirl How 802 2631 Southern 33 Kirk Fell 802 2631 Western 34 Green Gable 801 2628 Western 35 Lingmell 800 2625 Southern 36 Haycock 797 2615 Western 37 Brim Fell 796 2612 Southern 38 Dove Crag 792 2598 Eastern 39 Rampsgill Head 792 2598 Far Eastern 40 Grisedale Pike 791 2595 North Western 41 Watson's Dodd 789 2589 Eastern 42 Allen Crags 785 2575 Southern 43 Thornthwaite Crag 784 2572 Far Eastern 44 Glaramara 783 2569 Southern 45 Kidsty Pike 780 2559 Far -

Grasmere to Langdale Circular Pub-Crawl – 9.23 Miles

Grasmere to Langdale circular pub-crawl – 9.23 miles Directions 1. Park up in the scenic Grasmere village, then follow the road leading west out of the village around the edge of the lake and take the first footpath on your right, which hugs a wood before crossing a stile. 2. Stay on the track as it climbs up and up towards Silver How and meets the line of a dry-stone wall to your left. At the junction of paths, don’t veer left but carry straight on and follow the contour around the fell before twisting off to the right. 3. Keep going along the edge of the fell as the views of Elterwater and Windermere open up to your left, until you are standing above the waterfall cascading down below. You should see a track snaking down the gully beside the beck. Walk on a bit to the point where it meets the path you’re on and then take it and head sharply down alongside the water towards Langdale. 4. Cross the little road you meet that leads through the village of Chapel Stile, and cut across the meadow ahead of you to reach the first pub - Wainwrights Inn.* 5. When you leave the pub walk past its beautiful beer garden and take a sharp right over a footbridge that crosses Great Langdale Beck. 6. Turn right and follow the path up as it first skirts and then rises to pass through an old (but still working) slate quarry. Stay on the track until you’ve left the quarry and meet a little house on your right. -

Dooker Beck Easedale Road, Grasmere, LA22 9QH

Dooker Beck Easedale Road, Grasmere, LA22 9QH Price £599,950 www.matthewsbenjamin.co.uk Dooker Beck Easedale Road, Grasmere The sale of Dooker Beck offers an unusual opportunity to acquire a substantial and well proportioned three/four bedroom detached timber framed property build under a pitched slate roof. Enviably positioned on an excellent plot which enjoys superb fell and country views especially from the large picture windows that also allow an enormous amount of light into the property. Whilst both the front and rear attractive yet manageable grounds enjoys fabulous fell views. There is a generous parking facility allowing six vehicles in addition to the detached garage. Additionally the property also enjoys the benefit of planning permission within the garden to construct a new double storey three bedroom/two bath room detached dwelling. Planning reference 7/2014/5747. Please note this will have a local occupancy restriction. Please contact the office for more details. Easedale Road leads away from the centre of Grasmere village into the peaceful valley of Easedale and from the property there are amazing views to both front and rear across fields and fells. This level position offers a comfortable walk into the centre of Grasmere and from the doorstep there are a wide range of fell and country walks to choose from. Private off road parking is a significant advantage to the property. www.matthewsbenjamin.co.uk From the centre of the village and Red Lion Square turn left after the Heaton Cooper Studio onto Easedale Road. Continue along the lane for approximately 1/4 mile and the property is on the right hand side five properties after High Fieldside. -

Langdale the Langdale Pikes and Bowfell

WALKING THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS LANGDALE THE LANGDALE PIKES AND BOWFELL by MARK RICHARDS CICERONE CONTENTS © Mark Richards 2019 Second edition 2019 Map key ..................................................5 ISBN: 978 1 78631 032 3 Volumes in the series .........................................6 Author preface ..............................................9 Originally published as Lakeland Fellranger, 2009 Starting points ..............................................10 ISBN: 978 1 85284 543 8 INTRODUCTION ..........................................13 Printed in China on behalf of Latitude Press Ltd Valley bases ...............................................13 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Fix the Fells ...............................................15 All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. Using this guide ............................................16 All artwork is by the author. Safety and access ...........................................18 Additional online resources ...................................19 Maps are reproduced with permission from HARVEY Maps, www.harveymaps.co.uk FELLS ...................................................20 1 Blea Rigg...............................................20 2 Bowfell ................................................30 3 Calf Crag...............................................42 Updates to this Guide 4 Cold Pike ..............................................48 While every effort is made by our authors to ensure the accuracy of guide- -

Wain No Name Wain Ht District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell Pike

Wain no Name Wain ht District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell Pike 3210 SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell Pike from Scafell 2 Scafell 3162 SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell 3 Helvellyn 3118 EAST HELVELLYN y map Helvellyn summit 4 Skiddaw 3053 NORTH SKIDDAW y map Skiddaw 5 Great End 2984 SOUTH SCAFELL y map Great End 6 Bowfell 2960 SOUTH BOWFELL y map Bowfell from Crinkle Crags 7 Great Gable 2949 WEST GABLE y map Great Gable from the Corridor Route 8 Pillar 2927 WEST PILLAR y map Pillar from Kirk Fell 9 Nethermost Pike 2920 EAST HELVELLYN y map Nethermost Pike summit 10 Catstycam 2917 EAST HELVELLYN y map Catstycam 11 Esk Pike 2903 SOUTH BOWFELL y map Esk Pike 12 Raise 2889 EAST HELVELLYN y map Raise from White Side 13 Fairfield 2863 EAST FAIRFIELD y map Fairfield from Gavel Pike 14 Blencathra 2847 NORTH BLENCATHRA y map Blencathra 15 Skiddaw Little Man 2837 NORTH SKIDDAW y map Skiddaw Little Man 16 White Side 2832 EAST HELVELLYN y map White Side summit 17 Crinkle Crags 2816 SOUTH CRINKLE CRAGS y map Crinkle Crags from Pike O' Blisco 18 Dollywaggon Pike 2810 EAST HELVELLYN y map Dollywaggon Pike 19 Great Dodd 2807 EAST DODDS y map Great Dodd 20 Grasmoor 2791 NORTH-WEST GRASMOOR y map Grasmoor 21 Stybarrow Dodd 2770 EAST DODDS y map Stybarrow Dodd across Sticks Pass 22 Scoat Fell 2760 WEST PILLAR y map Scoat Fell's summit 23 St Sunday Crag 2756 EAST FAIRFIELD y map St Sunday Crag from Birks 24 Crag Hill [Eel Crag] 2749 NORTH-WEST COLEDALE y map Crag Hill from Grasmoor 25 High Street 2718 FAR-EAST HIGH STREET y map High Street 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 2707 -

Glenthorne Guest House and Conference Centre Easedale Road, ,Grasmere

Glenthorne Guest House and Conference Centre Easedale Road, ,Grasmere. Ambleside. Cumbria. LA22 9QH Telephone / Fax: 015394 35389. Email: [email protected]. WEB: www.glenthorne.or g Hello from Glenthorne! The snow drops have been in flower for the last two weeks and Glenthorne has opened for the season! The day after Valentine's day, the garden birds were singing in the sunshine, we heard our first woodpeckers of the year hammering in the nearby woods and the tawny owls were calling to each other after dusk. We have seen red squirrels in the garden several times already and Alex (our gardener) has been frustrated by the roe deer nibbling the daffodils again. This year we are offering more special interest holidays, both at the weekends and during the week. The old favourites such as Patchwork Quilting, Boat, Boot and Goat and Circle Dancing are on the programme along with new additions such as Alison Lock's Transformative Life Writing course at the end of March, Linda Hoy's Labyrinth – Exploring the spiritual journey in words and fabric and Quakerly Yoga with Mary Cleary from North Carolina Meeting. Later in the year we look forward to Ben Pink Dandelion's Transforming Quakerism and Naming our Spiritual Gifts with Thomas Swain of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. We have kept our room prices the same as last year and we have some great special offers available at the moment. It is a great base to walk and explore from. Some of us have been out walking in the fells already: - Helm Crag, Tarn Crag, Silver How, Easedale Tarn and Wainwright's coast to coast walk are at our door. -

Wainwright Poster

CP5 arrive Hillingdon Athletic Club CP5 leave 49 Whin Rigg 50 Illgill Head 51 Slight Side 52 Scafell 53 Lingmell Fell Runner Steve Birkinshaw attempts to 54 Scafell Pike 55 Great End break the 27 year old record of completing a 56 Esk Pike circuit of all the 214 Lakeland Wainwright 57 Rossett Pike 58 Bowfell summits in under seven days 59 Crinkle Crags 60 Pike o’Blisco 61 Cold Pike 62 Hard Knott CP6 arrive CP6 leave 63 Harter Fell 64 Green Crag Wainwright CP7 arrive CP7 leave 65 Dow Crag 66 Coniston Old Man record attempt 67 Brim Fell 68 Grey Friar 69 Great Carrs 70 Swirl How 320 miles, 36,000 metres of ascent – the 71 Wetherlam equivalent of two marathons a day and up CP8 arrive CP8 leave and down Everest four times 72 Holme Fell 73 Black Fell 74 Lingmoor Fell Alastair Lee ’s film of the attempt will be CP9 arrive shown at the Hillingdon AC clubhouse on CP9 leave 75 Loft Crag Friday 15 April 2016 at 8 pm 76 Pike o’Stickle 77 Harrison Stickle 78 Pavey Ark A brief contextual introduction will be given by 79 Thunacar Knott 80 Sergeant Man Howard Pattinson, Bob Graham 24 Hour Club 81 High Raise member number 55 82 Sergeant’s Crag 83 Eagle Crag 84 Ullscarf 85 Steel Fell 86 Calf Crag 87 Gibson Knot 88 Helm Crag 89 Tarn Crag 90 Blea Rigg 91 Silver How 92 Loughrigg Fell CP10 arrive CP10 leave 93 Nab Scar 94 Heron Pike 95 Stone Arthur 96 Great Rigg 97 Seat Sandal 98 Fairfield 99 Hart Crag 100 Hartsop above How 101 Dove Crag 102 High Pike 103 Low Pike 104 Little Hart Crag 105 High Harsop Dodd 106 Middle Dodd Admission on the door £5 107 Red Screes All proceeds to the MS Society CP11 arrive CP11 leave. -

Hts Walking the Wainwrights 64 Walks to Climb the 214 Wainwrights of Lakeland

Walking the Wainwrights Walking Walking the Wainwrights Walking the Wainwrights 64 WALKS TO CLIMB THE 214 WAINWRIGHTS OF LAKELAND 64 WALKS TO CLIMB THE 214 WAINWRIGHTS OF LAKELAND In this book you’ll find 64 routes that, if you complete them all, by default you will also have completed the Wainwrights. A few of the summits are featured in more than one walk. That’s ok. You can do them more than once! Why do we need a guide book on the fells of the Lake District if Wainwright wrote seven of them? Well, I should say right here that this book is not intended to replace Wainwright’s UneyGraham Pictorial Guides. They are superb books. But, they were written in the 1950s and 60s, and yes, some things in the hills have changed in the intervening years. Another reason is that many walkers struggle to devise full-day walks using the Wainwright guide books. Yes, he has detailed pretty much every conceivable way of getting to each individual summit, but this leaves the reader having to then come up with their own plan to make a longer day of it by continuing over one or more other fells. Wainwright didn’t describe day walks in these seven guidebooks. He described individual ways up and down each one. So, please buy the Wainwright guidebooks if you haven’t got them on your bookshelves already. Just 9 781906 095789 use them alongside this book. Cover – On Rannerdale Knotts with the bulk of Robinson behind (Walk 54). Back cover – The Buttermere Fells and Grasmoor seen from Haycock (Walk 63). -

Route Directions Great Langdale

ESSENTIAL INFO HIGH FELL Grade: Easy walk on good paths Distance: 6 miles Allow: 3.5 hours plus any stops Start/Finish: Elterwater National Trust Car Park, OS Grid Ref: GR 328 047 Maps: Explorer OL6 & OL7 Parking: Elterwater National Trust Car Park THE CUMBRIA Public transport: Langdale Rambler, Bus Service 516, Ambleside-Dungeon Ghyll LANDSCAPE STORY Facilities: WCs, shops, pubs in Elterwater and Chapel Stile. Several pubs also en-route Equipment: Sturdy footwear, waterproofs and light refreshments THE GREAT LANGDALE THE GREAT LANGDALE LANDSCAPE AUDIO TRAIL LANDSCAPE AUDIO TRAIL This audio trail is part of Cumbria Contact: Cumbria’s fells have been shaped by wildlife-rich hay meadows of days Wildlife Trust’s oral history project: Cumbria Wildlife Trust, Plumgarths man for thousands of years, but the gone by. Listen to the memories and High Fell – The Cumbria Landscape Crook Road, Kendal, Cumbria LA8 8LX period after World War II was a time of stories of the people who remember Story. Visit the High Fell website to find radical change, which influenced the the landscape, its wildlife, and the Tel: 01539 816 300 out about the project. Email: [email protected] landscape we see today. transformations that have taken place www.cumbriawildlifetrust.org.uk/ Registered charity no.218711 since the 1940s. highfellstory This audio trail will guide you through the history of the Great Langdale Download the audio trail MP3 files or landscape. You’ll learn about the transcript from the High Fell website: revolution in farming, explore traditional www.cumbriawildlifetrust.org.uk/ woodland practices, and discover the highfellstory/walk 4 Designed by www.fluiddesignstudio.com 1 ROUTE DIRECTIONS GREAT LANGDALE Listen to the audio tracks as you follow the map along the walk route.