How Presentation of Electronic Resource Gateway Pages Impact Student Research Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New York Public Library Connections Connections 2015 2015

The New York Public Library Connections Connections 2015 Connections 2015 A guide for formerly incarcerated people in New York City The New York Public Library Public York New The Twentieth Edition Winter/Spring 2015 The New York Public Library Connections 2015 A guide for formerly incarcerated people in New York City Twentieth Edition edited by the Correctional Services Staff of The New York Public Library Connections 2015 Single copies of Connections are available free of charge to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people throughout New York State, as well as to staff members of agencies and others who provide services to them. Send all requests to: Correctional Library Services The New York Public Library 445 Fifth Avenue, 6th floor New York, NY 10016 Connections is also available online at: nypl.org/corrections CONNECTIONS 2015 CONNECTIONS 2 © The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, 2015 All rights reserved The name “The New York Public Library” and the representation of the lion appearing in this work are registered marks and the property of The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Twentieth edition published 2015 ISBN: 978-0-87104-795-3 Cover design by Eric Butler About This Directory The purpose of Connections is to offer people leaving jail and prison helpful resources available to them in New York City. Every agency listed in Connections has been personally contacted in order to provide you with current and relevant information. Where list- ings could not be verified by phone, the organization websites were accessed to cull basic program and contact information. -

Market Garden Is Open to the Public Tuesday Through Sunday from April Through October

JMG Horticulturist & Landscape Designer since 1999: Susan Sipos Weather permitting, Jefferson Market Garden is open to the public Tuesday through Sunday from April through October. Jefferson Market To learn more about Jefferson Market Garden, contact us at: Jefferson Market Garden 70A Greenwich Avenue PMB 372 New York, NY 10011-8358 Email: [email protected] Publication created by www.jeffersonmarketgarden.org Map: George Colbert Photographs: Laurie Moody, Bill Thomas, Linda Camardo Publication Design: Anne LaFond, Partnerships for Parks © 2014 facebook.com/jeffersonmarketgarden JefferSOn MArkeT GArden on Greenwich JOIn US! BeCOMe A frIend Of THe GArden! Avenue between Sixth Avenue and West 10th Street Jefferson Market Garden belongs to everyone. is a lush oasis in the heart of Greenwich Village, Whether you visit once a year, once a week or one of Manhattan’s great historic neighborhoods. every day, the Garden will be enriched by your The Garden and the neighboring public library are participation. Although New York City retains both named for an open farmers market located there in the early 19th century and leveled in 1873 ownership of the land through the NYC Department to make room for an ornate Victorian courthouse of Parks and Recreation, the Garden’s upkeep is the designed by Vaux and Withers. responsibility of a community group of volunteers. In 1931, a prison, The Women’s House of Detention, Gardens are fragile and require constant attention was built. In the 60’s when the City threatened to and renewal. Your contributions enable the Garden’s demolish the courthouse, the community organized plants, shrubs, and trees to be maintained in to save it for use as a public library and then splendid seasonal bloom. -

Hunter College Libraries Annual Report 2013-2014

CUNY - HUNTER COLLEGE Hunter College Libraries Annual Report 2013-2014 Dan Cherubin Associate Dean, Chief Librarian Table of Contents I. Summary of Accomplishments and Progress A. Faculty/Staff Activity and Success 1. FY 2013-2014 Library Faculty Awards and Recognition II. Library Usage and Facilities A. Facilities Updates B. Library Usage 1. Door Counts 2. Circulation of Materials 3. A/V Loans 4. Inter-library Loans (ILL) 5. eReserves and Copyright C. User Data 1. Reference a) Desk Reference Transactions b) Chat Reference Transactions c) Research Consultations – Students 2. Instruction a) Other Library-related instructional initiatives III. Collection Development and Electronic Resources A. Printed Material and Cataloging B. Website C. Electronic Resources – External IV. Administration and Budget A. Personnel and Staffing Requests B. Facilities Requests C. Budget requests 1. Library (01) 2. Library Acquisitions (03) V. Major Goals VI. Report Preparation and Dissemination I am pleased to submit the Annual Report for the Hunter College Libraries for FY 2013-2014. I. Summary of Accomplishments and Progress A. Faculty/Staff Activity and Success FY 2013-2014 marks another year of some sad farewells to long time Library team members. Harry Johnson, our Circulation Manager, retired after more than 25 years on the job. Associate Professor Patricia Woodard, who had served in many capabilities but most importantly as our liaison to Music, Romance Languages, German and the Department of Accessibility, retired in early April. And Assistant Professor Jonathan Cain left at the end of the year to take a position at the University of Oregon. They will all be sorely missed. We were, however, finally able to appoint two permanent positions that had been vacant for several years. -

Libraries March 24, 2011

New York City Council Christine C. Quinn, Speaker Finance Division Preston Niblack, Director Jeffrey Rodus, First Deputy Director Hearing on the Mayor’s Fiscal Year 2012 Preliminary Budget & the Fiscal Year 2011 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report Libraries March 24, 2011 Committee on Cultural Affairs, Libraries and International Intergroup Relations Hon. James Van Bramer, Chair Joint with Select Committee on Libraries Hon. Vincent Gentile, Chair Latonia McKinney,Deputy Director, Finance Division Shadawn Smith, Principal Legislative Financial Analyst Finance Division Briefing Paper Libraries Summary and Impact Library services are provided through three independent systems: the Brooklyn Public Library (BPL), the New York Public Library (NYPL) and the Queens Borough Public Library (QBPL). These systems operate 209 local library branches throughout the City and four research library centers in Manhattan. The libraries offer free and open access to books, periodicals, electronic resources and non-print materials. Reference and career services, Internet access, and educational, cultural and recreational programming for adults, young adults and children are also provided. The libraries’ collections include 377 electronic databases and more than 65 million books, periodicals and other circulating and reference items. The City provides for both direct operating support and energy costs in all facilities, which it does in part through prepayments in the current fiscal year. Financial Summary for the Libraries Dollars in Thousands (Adjusted for prepayments.) 2009 2010 2011 2011 2012 Difference Actual Actual Adopted Feb Plan Feb Plan 2012–2011* Research Libraries $31,946 $37,436 $23,000 $21,758 $17,452 ($5,548) NYPL 134,127 118,489 115,344 109,041 85,182 ($30,162) BPL 100,472 88,957 85,969 79,577 63,328 ($22,642) QBPL 99,763 87,156 84,197 81,268 61,342 ($22,856) TOTAL $366,308 $332,038 $308,510 $291,644 $227,303 ($81,207) * Difference refers to the variance between the Fiscal 2011 Adopted Budget and the Fiscal 2012 February Budget. -

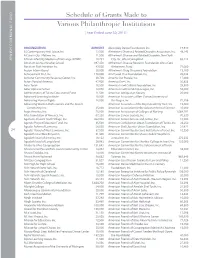

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Extension Attached

F.; ATTACHED .r EXTENSION OMB No 1545-0047 Form 9 9 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung 2005 benefit trust or private foundation) Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year, or tax year beginning , and ending C Name of organization D Employer identification number B Check if applicable Please Address change use IRS The New York Communi ty Trust 13-3062214 label or Name change print or Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/sui te E Telephone number type Initial return 909 Third Avenue 22nd Fl 212-686-0010 Specific City or town State or country ZIP + 4 F Accounting method : Cash []Accrual Final return Instruc- lions Amended return New York NY 10022-4752 (specify) ► Application pending • Section 501 (c)(3) organizations and 4947 (a)(1) nonexempt charitable H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? q Yes No G Website : ► www.nycommunitytrust. org H(b) If 'Yes,' enter number of affiliates ► 2_ H(c) Are all affiliates included? Yes No J Organization type (check only one) ► E501 (c) ( 3 ) 4 (insert no) ^4947(a)(1) or 0527 (if 'No,* attach a list See instructions ) K Check here the organization's gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 The H(d) Is this a separate return filed by an o an zatiion organization need not file a return with the IRS, but if the organization chooses to file a return, be covered by a group ruling? Yes a No sure to file a complete return Some states require a complete return . -

THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE of ARCHITECTS and the AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Library Administration and Management Association Reci

THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS and THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Library Administration and Management Association Recipients, Library Buildings Award Program 1963~1993 THE AMERICA."'! INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS and THE AMERICAN UBRARY ASSOCIATION Library Adminis!Tation and Management Association Recipients, Library Buildings Award Program 1963 FIRST HONOR AWARD Ben.'lington College Library Bennington, Vermont Pietro Belluschi & Carl Koch & Associates, Architects Skokie Public Library Skokie, lllinois Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Architects Undergraduate Library University of South Carolina Columbia, South Carolina Lyles, Bissett, Carlisle & Wolff, Architects Walnut Hill Branch Dallas Public Library Dallas, Texas J. Hershel Fisher & Donald E. Jarvis, Architects AWARD OF MERIT Burling Library Grinnell College Grinnell,. lotva Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Architects Douglass College Library Rutgers State University New Brunswick, New Jersey \Varner, Burns1 Toan, Lunde, Architects Flossmoor Public Library Flossmoor, Illinois McPherson-Swing & Associates, Architects Foothill College Library Los Altos Hills, California Ernest J. Kump & Masten & Hurd, Architects Louisiana State Library Baton Rouge, Louisiana William L. Pereira & Associates, Architects 1 Lourdes Library Gwynedd Mercy Junior College Gwynedd Valley, Pennsylvania Nolen-Swinburne & Associates, Architects New Orleans Public Library Main Library New Orleans, Louisiana Curtis & Davis, Goldstein, Parham & Labouisse, Favrot, Reed, Mat.'les & Bergman Associates, Architects Schulz -

Guide to the Libr Aries 2013-14 Welcome

Guide to the Libr aries 2013-14 Welcome Columbia University Libraries/Information Services is a system of 22 libraries, including affiliates, offering extensive print and electronic resources, discipline-based digital centers, and a team of expert staff providing innovative services to support instruction and scholarship. Over 12 million volumes are available at the Libraries and online, as well as extensive electronic resources, manuscripts, rare books, microforms, maps, and more. The website of the Libraries, library.columbia.edu, connects you to our search and discovery system, services and resources, digital collections, research assistance, and more. Welcome to the Libraries! James G. Neal Vice President for Information Services & University Librarian Library Information Office (LIO) Located at the entrance of Butler Library, the Library Information Office answers general questions about all of the Libraries’ services and resources. Visit LIO to pay fines and clear blocks on your library account or inquire about visitor passes and printing dollars for visitors and alumni. Office of Disability Services (ODS) Columbia University is committed to ensuring that the services and programs offered by the Libraries are accessible to all patrons. The University will work with patrons on an individual basis to assess their accommodation needs. For more information, please visit the ODS online at library.columbia.edu/services/lio/ disability.html. Alumni Services With an alumni card, all Columbia University graduates can access the Columbia University Libraries. Borrowing privileges are available for a fee. You can obtain an alumni card at the Library Information Office. Off-campus access to select, online databases are available as a courtesy to all alumni. -

College and Research Libraries

New Members ERMANENT membership records have been kept only since 1946—so in this listing members Pjoining during the period Jan. i-Apr. 1, 1948, are called "new" if they did not belong in either 1946 or 1947. Because of various factors there may be an unusual degree of error in this first listing. We would appreciate your help in making our records accurate. So would you please notify N. Orwin Rush, Executive Secretary, 50 E. Huron St., Chicago 11, of any corrections which should be made. New institutional members will appear in a later listing. Ackley, Mrs. Corinne B., University of Washington Bell, Bernice K., Wesley Junior College Adams, Dorothy Jeanette, Riverside, Calif., Central Bellingham, Harold, University of Denver Junior High Bennett, Melvin, Kent Library (Cape Girardeau, Mo.l Adams, Florence Elizabeth, Yale University Bentz, Dale M., East Carolina Teachers College (Green- Aguayo, Jorge, Universidad de la Habana ville, N.C.) Alexander, Leona May, Oakland, Calif., Public Library Berg, Virginia A., University of Illinois Alexander, Virginia, University of South Carolina Bevis, Leura Dorothy, University of Washington Alford, Attie A., Florida State University Bielby, Ruth M., Syracuse University Alford, Ruth Virginia, University of Delaware Billington, Donna Jean, Harris College of Nursing Amesse, Helen M., University of Denver Bishop, Amie-Louise, University of Colorado Anders, Richard Lear, Champaign, Illinois Bishop, Mrs. Ethel Langdon, Nebraska Wesleyan Uni- Anderson, Geraldine D., Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal versity Co. -

THE CITY of NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4Th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533- 5300 - [email protected]

THE CITY OF NEW YORK MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD 3 59 East 4th Street - New York, NY 10003 Phone (212) 533- 5300 www.cb3manhattan.org - [email protected] Jamie Rogers, Board Chair Susan Stetzer, District Manager September 2016 Full Board Minutes Meeting of Community Board 3 held on Tuesday, September 27, 2016 at 6:30pm at PS 20, 166 Essex Street. Public Session: Robyn Shapiro/ Justin Rivera: Speaking on behalf of the Lowline. They are updating community on the Lowline's status and to inform the public about the Lowline Lab located on Essex Street. She also informed the community of High School Internship program where High Schoolers have opportunity to work with the Lowline. Cathy O' Sullivan: Updating community about a start up Alzheimer's and Dementia program in the neighborhood, services are free. Michael Lolan/Wendy Cheung: Speaking on behalf of Coalition to Protect Chinatown. Speaking in support of CB3 fully supporting the Chinatown Working Group's rezoning plan. Alex Kelly: speaking on behalf of the New York Public Library, she is inviting the community to sign up for one of the local public libraries oral history project to help record neighborhood history. Ian Nolan: Speaking on behalf of the Public Art Festival Art in Odd Places. Seeking volunteer and contributions to an audio tour of 14th street. Vaylateena Jones: Informing community of students in particular schools who are scoring low on reading test. Advocating for comprehensive literacy approach for 2nd graders. Also advocating for COMPASS After-School program. Harry Bubbios: Speaking on behalf of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. -

The Achelis and Bodman Foundation 2017 Grants Arts and Culture

The Achelis and Bodman Foundation 2017 Grants Arts and Culture American Ballet Theatre $25,000 New York, New York For general operating support American Museum of Natural History $50,000 New York, New York To support a new walk-up overhead scanner for the Research Library ($25,000) and to create archival records of temporary exhibits ($25,000) Americas Society $15,000 New York, New York For an exhibition, The Metropolis in Latin America (1830-1930) Bronx River Alliance $25,000 Bronx, New York For general operating support Brooklyn Academy of Music $50,000 Brooklyn, New York To support BAM Theater Brooklyn Botanic Garden $50,000 Brooklyn, New York For general operating support Center for Jewish History $25,000 New York, New York To support an exhibition, 500 Years of Treasures from Oxford Clarion Music Society $50,000 New York, New York To support the 2017-18 season Drama League $15,000 New York, New York To support the Directors Project Page 1 Glimmerglass Festival $50,000 Cooperstown, New York To support the 2017 season Solomon Guggenheim Museum $25,000 New York, New York For general operating support Cora Hartshorn Arboretum and Bird Sanctuary $15,000 Short Hills, New Jersey To support forest restoration Hispanic Society Museum & Library $50,000 New York, New York For general operating support Library of America $50,000 New York, New York To support the publication of The Diaries of John Quincy Adams: 1779-1848 Little Orchestra Society $20,000 New York, New York For general operating support Metropolitan Museum of Art $50,000 New York, -

HAMILTON GRANGE BRANCH of the NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY, 503-505 ~Jest I 45Th Street, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission ~ft a rch 31, 1970, Number 2 LP-0599 HAMILTON GRANGE BRANCH OF THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY, 503-505 ~Jest I 45th Street, Borough of Manhattan. Begun 1905, completed 1906; architects McKim, Mead & White. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 2077, Lot 26. On December 27, 1966, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a publ lc hearing on the proposed designation as a La~dmark of the Hamilton Grange Branch of the New York Publ lc Library and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site. (Item No. 89). The hearing was continued until January 31, 1967 (Item No. 35). At that time, a letter was submitted from the attorneys for the New York Public Library, and two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Hami !ton Grange Branch Library, bui It by McKim, Mead & ~/hite in 1905-6 in the style of the !tal ian Renaissance, has the true character of a Florentine palazzo. This three-story stone bui !ding shows the sensitivity to proportion, re~ation of elements and scale, which is found in the best examples of the style. Order and unity pervade a composition which in its major architectural elements is quite dynamic. Characteristic of the style, the openings are the major elements. The openings are graded from the large, round arched door and windows of the first floor; to the rectangular, pedimented windows of the second story, to the smal fer, evenly spaced windows of the third story. There are narrow windows between the larger ones, which also are aligned one above the other, but they are graduated the opposite way: from smallest at the first story to widest at the third.