AIA Allen Final Pages 9/18/02 1:36 PM Page Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________May 22, 2008 I, _________________________________________________________,Kristin Marie Barry hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Architecture in: College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning It is entitled: The New Archaeological Museum: Reuniting Place and Artifact This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Elizabeth Riorden _______________________________Rebecca Williamson _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The New Archaeological Museum: Reuniting Place and Artifact Kristin Barry Bachelor of Science in Architecture University of Cincinnati May 30, 2008 Submittal for Master of Architecture Degree College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning Prof. Elizabeth Riorden Abstract Although various resources have been provided at archaeological ruins for site interpretation, a recent change in education trends has led to a wider audience attending many international archaeological sites. An innovation in museum typology is needed to help tourists interpret the artifacts that been found at the site in a contextual manner. Through a study of literature by experts such as Victoria Newhouse, Stephen Wells, and other authors, and by analyzing successful interpretive center projects, I have developed a document outlining the reasons for on-site interpretive centers and their functions and used this material in a case study at the site of ancient Troy. My study produced a research document regarding museology and design strategy for the physical building, and will be applicable to any new construction on a sensitive site. I hope to establish a precedent that sites can use when adapting to this new type of visitors. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank a number of people for their support while I have been completing this program. -

Turkeyâ•Žs Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities

International Journal of Legal Information the Official Journal of the International Association of Law Libraries Volume 38 Article 12 Issue 2 Summer 2010 7-1-2010 Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities Kathleen Price Levin College of Law, University of Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli The International Journal of Legal Information is produced by The nI ternational Association of Law Libraries. Recommended Citation Price, Kathleen (2010) "Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities," International Journal of Legal Information: Vol. 38: Iss. 2, Article 12. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli/vol38/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Legal Information by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities KATHLEEN PRICE* “Every flower is beautiful in its own garden. Every antiquity is beautiful in its own country.” --Sign in Ephesus Museum lobby, quoted in Lonely Planet Turkey (11th ed.) at 60. “History is beautiful where it belongs.”—OzgenAcar[Acar Erghan] , imprinted on posters in Turkish libraries, classrooms, public buildings and shops and quoted in S. Waxman, Loot at 151; see also S. Waxman ,Chasing the Lydian Hoard, Smithsonian.com, November 14, 2008. The movement of cultural property1 from the vanquished to the victorious is as old as history. -

Minoan Religion

MINOAN RELIGION Ritual, Image, and Symbol NANNO MARINATOS MINOAN RELIGION STUDIES IN COMPARATIVE RELIGION Frederick M. Denny, Editor The Holy Book in Comparative Perspective Arjuna in the Mahabharata: Edited by Frederick M. Denny and Where Krishna Is, There Is Victory Rodney L. Taylor By Ruth Cecily Katz Dr. Strangegod: Ethics, Wealth, and Salvation: On the Symbolic Meaning of Nuclear Weapons A Study in Buddhist Social Ethics By Ira Chernus Edited by Russell F. Sizemore and Donald K. Swearer Native American Religious Action: A Performance Approach to Religion By Ritual Criticism: Sam Gill Case Studies in Its Practice, Essays on Its Theory By Ronald L. Grimes The Confucian Way of Contemplation: Okada Takehiko and the Tradition of The Dragons of Tiananmen: Quiet-Sitting Beijing as a Sacred City By By Rodney L. Taylor Jeffrey F. Meyer Human Rights and the Conflict of Cultures: The Other Sides of Paradise: Western and Islamic Perspectives Explorations into the Religious Meanings on Religious Liberty of Domestic Space in Islam By David Little, John Kelsay, By Juan Eduardo Campo and Abdulaziz A. Sachedina Sacred Masks: Deceptions and Revelations By Henry Pernet The Munshidin of Egypt: Their World and Their Song The Third Disestablishment: By Earle H. Waugh Regional Difference in Religion and Personal Autonomy 77u' Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: By Phillip E. Hammond Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image, and Symbol By By George D. Bond Nanno Marinatos A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam By Gordon Darnell Newby MINOAN RELIGION Ritual, Image, and Symbol NANNO MARINATOS University of South Carolina Press Copyright © 1993 University of South Carolina Published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marinatos, Nanno. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

238 Linear Feet Creator Annie Smith Peck

BROOKLYN COLLEGE LIBRARY ARCHIVES & SPECIAL COLLECTIONS 2900 BEDFORD AVENUE BROOKLYN NEW YORK 11210 718.951.5346 http://library.brooklyn.cuny.edu THE ANNIE SMITH PECK COLLECTION Accession #89-002 Dates Bulk dates: 1873-1935 Extent 16.5 cubic feet; 238 linear feet Creator Annie Smith Peck (1850-1935) Access / Use The Collection is open for research. Copyright is retained by Brooklyn College. Files can be accessed at the Brooklyn College Library Archives & Special Collection, 2900 Bedford Ave., Brooklyn, New York, Main floor (Room 130). 1 Languages English, German, Greek and Latin Finding aid Guide presently available in-house and on-line. Acquisition/Appraisal This collection was donated to Brooklyn College Archives by the late Prof. Shaista Rahman, Professor Emeritus of English, Brooklyn College. In 2016, additional correspondence was donated by Hannah Kimberley. Description Control: Guide adheres to that prescribed by Describing Archives: A Content Standard. Preferred Citation Item, folder title, box number, The Annie Smith Peck Collection, Brooklyn College Archives & Special Collections, Brooklyn College Library Subject Heading Peck, Annie S., 1850-1935. South America -- Economic conditions -- 1918-1961. South America -- Description and travel. Mountaineering. Peru -- Description and travel. Bolivia -- Description and travel. Huascaran Mountain (Peru). Related Materials New York Times newspaper 1908-1934 2 Biographical Note Annie Smith Peck (1850-1935), scholar and mountaineer, was born in Providence, R. I., October 19, 1850, the youngest of five children of George Batchelder Peck and Ann Power Smith Peck. Mr. Peck (father) was a graduate of Brown University and a member of the Providence City Council with a successful law practice. He also owned a wood and coal yard. -

Important Women in United States History (Through the 20Th Century) (A Very Abbreviated List)

Important Women in United States History (through the 20th century) (a very abbreviated list) 1500s & 1600s Brought settlers seeking religious freedom to Gravesend at New Lady Deborah Moody Religious freedom, leadership 1586-1659 Amsterdam (later New York). She was a respected and important community leader. Banished from Boston by Puritans in 1637, due to her views on grace. In Religious freedom of expression 1591-1643 Anne Marbury Hutchinson New York, natives killed her and all but one of her children. She saved the life of Capt. John Smith at the hands of her father, Chief Native and English amity 1595-1617 Pocahontas Powhatan. Later married the famous John Rolfe. Met royalty in England. Thought to be North America's first feminist, Brent became one of the Margaret Brent Human rights; women's suffrage 1600-1669 largest landowners in Maryland. Aided in settling land dispute; raised armed volunteer group. One of America's first poets; Bradstreet's poetry was noted for its Anne Bradstreet Poetry 1612-1672 important historic content until mid-1800s publication of Contemplations , a book of religious poems. Wife of prominent Salem, Massachusetts, citizen, Parsons was acquitted Mary Bliss Parsons Illeged witchcraft 1628-1712 of witchcraft charges in the most documented and unusual witch hunt trial in colonial history. After her capture during King Philip's War, Rowlandson wrote famous Mary Rowlandson Colonial literature 1637-1710 firsthand accounting of 17th-century Indian life and its Colonial/Indian conflicts. 1700s A Georgia woman of mixed race, she and her husband started a fur trade Trading, interpreting 1700-1765 Mary Musgrove with the Creeks. -

Scholars Debate Homer's Troy

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 11, Number 3-4, Summer-Fall 2002 Appendix: Scholars Debate Homer’s Troy Hypothesis and the Science of History he main auditorium of the University of Tübingen, eries at the site of Troy (near today’s Hisarlik, Turkey) for TGermany was packed to the rafters for two days on more than a decade. In 2001 they coordinated an exhibi- February 15-16 of this year, with dozens fighting for tion, “Troy: Dream and Reality,” which has been wildly standing room. Newspaper and journal articles had popular, drawing hundreds of thousands to museums in drawn the attention of all scholarly Europe to a highly several German cities for six months. They gradually unusual, extended debate. Although Germany was hold- unearthed a grander, richer, and militarily tougher ing national elections, the opposed speakers were not ancient city than had been found there before, one that politicians; they were leading archeologists. The magnet comports with Homer’s Troy of the many gates and broad of controversy, which attracted more than 900 listeners, streets; moreover, not a small Greek town, but a great was the ancient city of Troy, and Homer, the deathless maritime city allied with the Hittite Empire. Where the bard who sang of the Trojan War, and thus sparked the famous Heinrich Schliemann, in the Nineteenth century, birth of Classical Greece out of the dark age which had showed that Homer truly pinpointed the location of Troy, followed that war. and of some of the long-vanished cities whose ships had One would never have expected such a turnout to hear sailed to attack it, Korfmann’s team has added evidence a scholarly debate over an issue of scientific principle. -

Where Is the Gap? of the EM III-MM IA Period in East Crete*

Matej Pavlacky Where is the gap? Of the EM III-MM IA period in East Crete* Abstract It has long been argued whether the EM III-MM IA period exists in East Crete and how it should be defined. There have been attempts to resolve the issue using ceramic material and/or stratigraphy; however, this issue has never been fully resolved. The EM III-MM IA period is now viewed as a time of major growth that gradually increases in complexity through MM I (Schoep 2006; Schoep et al. 2012) and is often explained through ideological and peaceful influence of elites on communities. There is also evidence for major urban and rural growth (Whitelaw 2012). Despite the data from regional surveys confirming the increased number of sites in East Crete, the gradual growth of sites can only be seen up until EM IIB. The increase of sites in EM III is rather rapid and cannot be explained only by natural generation growth. This paper examines and – where possible – provides answers to the two main questions, i.e. how to look at the EM III-MM IA period from the perspective of ceramics and stratigraphy at Priniatikos Pyrgos, and what is the background of the decline of Priniatikos Pyrgos after EM III-MM IA. Keywords: late Prepalatial period, Early Minoan period, Middle Minoan period, settlement, pottery, elites, chronology Introduction It has been long argued whether the truly fascinating EM III - MM IA period exists in East Crete or not, how it should be defined, if it should be counted as one or whether it can be divided into two separate parts (EM III and MM IA), or if there simply is just “an” EM III or MM IA phase respectively. -

Minoans in New York

AJA ONLINE PUBLICATIONS: MUSEUM REVIEW MINOANS IN NEW YORK BY roBERT B. KOEHL FROM THE LAND OF THE LABYRINTH: MINOAN CRETE, cently opened study collection of Greek and 3000–1100 B.C., ONASSIS CULTURAL CENTER, Roman art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art NEW YORK, 13 MARCH–13 SEPTEMBER, 2008, includes representative Minoan artifacts with curated by Maria Andreadaki-Vlazaki, provenances, which supplement the museum’s Vili Apostolakou, and Nota Dimopoulou- regular display of artifacts with and without Rethemiotaki. provenances.3 A small exhibition of Minoan and Mycenaean objects from various American and FROM THE LAND OF THE LABYRINTH: MINOAN CRETE, European collections was mounted in 1967 at 3000–1100 B.C., edited by Maria Andreadaki- Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, Vlazaki, Giorgos Rethemiotakis, and Nota in memory of Harriet Boyd Hawes, a pioneer of Dimopoulou-Rethemiotaki. Pp. 295, b&w figs. Minoan archaeology.4 A Minoan exhibition in 29, color figs. 257, maps 2. Alexander S. Karlsruhe, Germany, in 2001 was mired in con- Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (USA) troversy for displaying undocumented Minoan and Hellenic Ministry of Culture, Archaeo- artifacts from a private collection alongside ma- logical Museums of Crete, Greece, 2008. $20. terial from archaeological museums on Crete ISBN 978-0-9776598-2-1 (paper). and other European public institutions. None of these moral dilemmas or questions Since opening its doors in New York City of authenticity need trouble the visitor to the in October 2000, the Onassis Cultural Center exhibition reviewed here. Culled exclusively has been host to a stream of splendid exhibi- from the archaeological museums of Crete—in tions largely devoted to introducing the North Haghios Nikolaos, Herakleion, Hierapetra, American public to the rich cultural heritage Khania, Rethymnon, and Siteia—most of the of Greece, both ancient and modern. -

American School of Classical Studies at Athens Newsletter Index 1977-2012 the Index Is Geared Toward Subjects, Sites, and Major

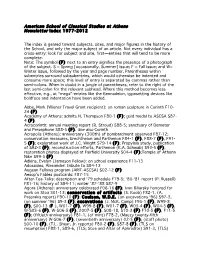

American School of Classical Studies at Athens Newsletter Index 1977-2012 The index is geared toward subjects, sites, and major figures in the history of the School, and only the major subject of an article. Not every individual has a cross-entry: look for subject and site, first—entries that will tend to be more complete. Note: The symbol (F) next to an entry signifies the presence of a photograph of the subject. S = Spring [occasionally, Summer] Issue; F = Fall Issue; and W= Winter Issue, followed by the year and page number. Parentheses within subentries surround subsubentries, which would otherwise be indented and consume more space; this level of entry is separated by commas rather than semi-colons. When in doubt in a jungle of parentheses, refer to the right of the last semi-colon for the relevant subhead. Where this method becomes less effective, e.g., at “mega”-entries like the Gennadeion, typesetting devices like boldface and indentation have been added. Abbe, Mark (Wiener Travel Grant recipient): on roman sculpture in Corinth F10- 24 (F) Academy of Athens: admits H. Thompson F80-1 (F); gold medal to ASCSA S87- 4 (F) Acrocorinth: annual meeting report (R. Stroud) S88-5; sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone S88-5 (F). See also Corinth Acropolis (Athens): anniversary (300th) of bombardment observed F87-12; conservation measures, Erechtheion and Parthenon F84-1 (F), F88-7 (F), F91- 5 (F); exploration work of J.C. Wright S79-14 (F); Propylaia study, publication of S92-3 (F); reconstruction efforts, Parthenon (K.A. Schwab) S93-5 (F); restoration photos displayed at Fairfield University S04-4 (F);Temple of Athena Nike S99-5 (F) Adkins, Evelyn (Jameson Fellow): on school experience F11-13 Adossides, Alexander: tribute to S84-13 Aegean Fellows program (ARIT-ASCSA) S02-12 (F) Aesop’s Fables postcards: F87-15 After-Tea-Talks: description and ‘79 schedule F79-5; ‘80-‘81 report (P. -

2020 Harriet Boyd Hawes Fellowship Application Guidelines

INSTAP STUDY CENTER FOR EAST CRETE Pacheia Ammos, Crete 72200 Greece 30-28420-93027, www.instapstudycenter.net 2020 HARRIET BOYD HAWES FELLOWSHIP APPLICATION GUIDELINES The INSTAP Study Center for East Crete is pleased to announce the availability of a fellowship to be awarded on a competitive basis to an eligible candidate for work to be done at the Study Center in Pacheia Ammos, Crete in 2020. This fellowship is aimed at the investigation of the role of women or gender studies in Bronze Age Crete. It is intended to highlight spheres and aspects of ancient life that have not yet received sufficient attention in Aegean Bronze Age studies. The fellowships are intended for scholars in the field of the Aegean Bronze Age/Early Iron Age who are working to complete their PhD dissertations or have completed their PhD Dissertations. The fellowship will be awarded in the amount of $3,000. Applications must be received by e-mail no later than February 1, 2020. Please send your applications and required information as attachments to [email protected]. The recipient of the award will be announced on March 1, 2020. In addition to the completed application form, proposals should include a curriculum vitae of the applicant, a page summarizing the title and intent of your intended project, an outline of the project, relevant bibliography, copies of appropriate permits, and two letters of support for the project by two colleagues. The fellowship is open to those holding or in. the. Process of completing a PhD in Archaeology, Anthropology, Art History, Ancient History, or Classics.