The Art of Co-Creating Arts-Based Possibility Spaces for Fostering STE(A)M Practices in Primary Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Against Transhumanism the Delusion of Technological Transcendence

Edition 1.0 Against Transhumanism The delusion of technological transcendence Richard A.L. Jones Preface About the author Richard Jones has written extensively on both the technical aspects of nanotechnology and its social and ethical implications; his book “Soft Machines: nanotechnology and life” is published by OUP. He has a first degree and PhD in physics from the University of Cam- bridge; after postdoctoral work at Cornell University he has held positions as Lecturer in Physics at Cambridge University and Profes- sor of Physics at Sheffield. His work as an experimental physicist concentrates on the properties of biological and synthetic macro- molecules at interfaces; he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 2006 and was awarded the Institute of Physics’s Tabor Medal for Nanoscience in 2009. His blog, on nanotechnology and science policy, can be found at Soft Machines. About this ebook This short work brings together some pieces that have previously appeared on my blog Soft Machines (chapters 2,4 and 5). Chapter 3 is adapted from an early draft of a piece that, in a much revised form, appeared in a special issue of the magazine IEEE Spectrum de- voted to the Singularity, under the title “Rupturing the Nanotech Rapture”. Version 1.0, 15 January 2016 The cover picture is The Ascension, by Benjamin West (1801). Source: Wikimedia Commons ii Transhumanism, technological change, and the Singularity 1 Rapid technological progress – progress that is obvious by setting off a runaway climate change event, that it will be no on the scale of an individual lifetime - is something we take longer compatible with civilization. -

The Upside of Disruption Megatrends Shaping 2016 and Beyond Contents

The upside of disruption Megatrends shaping 2016 and beyond Contents 4 Foreword 5 From disruption to megatrends 6 EY on disruption 8 Section 1: Understanding disruption 1. How did disruption become mainstream? 2. How is our understanding of disruption changing? 3. What are the root causes of disruption? 4. Why is responding to disruption so critical? 5. Why is it so difficult to respond to disruption? 6. How do businesses seize the upside of disruption? 7. How does disruption lead to megatrends? 18 Section 2: Megatrends 2016 1. Industry redefined 2. The future of smart 3. The future of work 4. Behavioral revolution 5. Empowered customer 6. Urban world 7. Health reimagined 8. Resourceful planet 52 How will you seize the upside of disruption? The upside of disruption Megatrends shaping 2016 and beyond 3 Foreword From disruption to megatrends Welcome to EY’s The Upside of Disruption. Disruption is As disruption becomes an everyday occurrence, we explore its everywhere and the future is uncertain — no one knows what the primary causes and the megatrends that are shaping our future world will look like even a decade from now. Our response is to help organizations find the opportunity in this challenge and ask: Disruption is fundamentally changing the way the world works. Today’s businesses, how do you seize the upside of disruption? government and individuals are responding to shifts that would have seemed unimaginable even a few years ago. Artificial intelligence and robotics are reinventing This report has been produced by EYQ, a new initiative from EY that will bring the workforce. -

Future Emerging Technology Trends

Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport DDPS armasuisse Science and Technology Emerging Technology Trends 2015 Thun 2015 Credits Editor Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport DDPS armasuisse Science and Technology Research Management and Operations Research www.armasuisse.ch/wt www.deftech.ch Author Dr. Quentin Ladetto Research Director - Technology Foresight [email protected] Release 1.3 Compiled on Tuesday 21st June, 2016 at 16:43 Front page: Emerging sun - view of the Earth from space Foreword As the rate of development in technology is accelerating and civil investments are pushing boundaries always closer to what was considered science-fiction until recently, the exploitation of dual-use technologies is growing in the defence & security ecosystem. If technology is not the only driver in the evolution of warfare, it is the enabler, not to say the trigger, of most of the changes that occurred at the turning point between generations. For a country like Switzerland, Technology Foresight is paramount to identify the opportuni- ties and threats a technology can represent for the different military capabilities building our national armed forces. Rather than picking winners, the Technology Foresight program must provide a comprehensive overview to ensure an early warning about novel relevant technological advances. Identifying potentialities provides the time to build the necessary competences, skills and expertise, in the various fields. In that sense, Technology Foresight must be an integrated element of the doctrine, planing and procurement processes of the armed forces. Only with this strategic futuristic vision, the Swiss armed forces are able to handle, economi- cally and operatively, the evolutions and challenges to come. -

Personalized Health Care: Opportunities, Pathways, Resources

Personalized Health Care: Opportunities, Pathways, Resources genomics • health information technology • evidence/clinical delivery September 2007 PERSONALIZED HEALTH CARE: OPPORTUNITIES, PATHWAYS, RESOURCES September 2007 United States Department of Health and Human Services CONTENTS Foreword by HHS Secretary Michael Leavitt...............................................................................................1 Opportunities: Envisioning a New Kind of Health Care .............................................................................3 Challenges: Prerequisites to Achieving Personalized Health Care ..........................................................7 Pathways: Building Blocks of Personalized Health Care...........................................................................9 Resources: HHS Programs Supporting Personalized Health Care .........................................................15 I. Expansion of the Science Base Human Genomics Research............................................................................................................15 Genome-Wide Association Studies .................................................................................................16 Genes, Environment and Health Initiative .......................................................................................18 Human Genome Epidemiology Network..........................................................................................19 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey..........................................................................20 -

Inorganic Chemistry for Dummies® Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc

Inorganic Chemistry Inorganic Chemistry by Michael L. Matson and Alvin W. Orbaek Inorganic Chemistry For Dummies® Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2013 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permis- sion of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley. com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. All other trade- marks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. -

Building the Cognitive Enterprise: Nine Action Areas

Research Insights Building the Cognitive Enterprise: Nine Action Areas Core Concepts Australia and New Zealand This Core Concepts Australia and New Zealand document is abridged from the in-depth version, “Building the Cognitive Enterprise: Nine Action Areas, Deep Dive” that also contains full-length case studies. Accelerating your digital transformation for the new normal We are at a tipping point in history where the impact of technology is so significant it can completely transform the way business is done. The convergence of technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), automation, Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain and 5G have the power to change business models, reinvent processes, and reimagine the way we all work. IBM calls this the emergence of the Cognitive EnterpriseTM. Add the extraordinary pressures in Australia Accelerating change and New Zealand organisations are facing with current global uncertainties, and we find While most organisations had already significant disruption in nearly every industry, embarked on digital transformations, the with some companies barely surviving and pandemic has made the need for change others thriving. much more urgent, with organisations turning to digital technologies to either help solve Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, pressing issues or scale up for growth. the rate of change has shifted into warp drive. Office towers emptied, with many people still Before the pandemic, the organisations working remotely. Supply chains were broken, seeking major transformations were typically and many businesses are still scrambling to either those struggling or high performers piece them back together. Industries changed ahead of the curve. Now, we are seeing the overnight, with some enjoying sudden booms business performance bell curve turned and others resigned to months or even years upside down, with even greater discrepancy of suppressed demand. -

Soft Machines: Copying Nature's Nanotechnology with Synthetic

From Fantastic Voyage to Soft Machines: two decades of nanotechnology visions (and some real achievements) Richard Jones University of Sheffield Three visions of nanotechnology… 1. Drexler’s mechanical vision 3. Quantum nanodevices 2. Biological/ soft machines … and two narratives about technological progress Accelerating change… …or innovation stagnation? Who invented nanotechnology? Richard Feynman (1918-1988) Theoretical Physicist, Nobel Laureate “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom” - 1959 Robert Heinlein? Norio Taniguchi? Coined the term “nanotechnology” in 1974 Don Eigler? 1994 – used the STM (invented by Binnig & Rohrer) to rearrange atoms “Engines of Creation” K. Eric Drexler 1986 The history of technology : increasing precision and miniaturisation Medieval macro- 19th century precision Modern micro-engineering engineering engineering MEMS device, Sandia Late medieval mine Babbage difference engine, pump, Agricola 1832 Where next? Nanotechnology as “the principles of mechanical engineering applied to chemistry” Ideas developed by K.Eric Drexler Computer graphics and simulation Technical objections to Drexler’s vision Drexler’s Nanosystems: More research required Josh Hall: “Noone has ever found a significant error in the technical argument. Drexler’s detractors in the political argument don’t even talk about it.” • Friction • Uncontrolled mechanosynthesis • Thermodynamic and kinetic stability of nanostructures • Tolerance • Implementation path • Low level mechanosynthesis steps “If x doesn’t work, we’ll just try y”, versus an ever- tightening design space. “Any material you like, as long as it’s diamond” • Nanosystems and subsequent MNT work concentrate on diamond – Strong and stiff (though not quite as stiff as graphite) – H-terminated C (111) is stable wrt surface reconstruction • Potential disadvantages – Not actually the thermodynamic ground state (depends on size and shape - clusters can reconstruct to diamond-filled fullerene onions) – Non-ideal electronic properties. -

LENS): Theory, Background, and Introduction

The Low Energy Neurofeedback System (LENS): Theory, Background, and Introduction Len Ochs, PhD SUMMARY. This article presents the concepts, operations, and history of the Low Energy Neurofeedback System (LENS) approach as they are now known and as it has evolved over the past 16 years. The conceptual bases and practical operating principles as described are quite differ- ent from those in traditional neurofeedback. The LENS, as a behavioral neurofeedback applica- tion, often provides the same qualitative outcome as that in traditional neurofeedback, with reduced treatment time. doi:10.1300/J184v10n02_02 [Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Web- site: <http://www.HaworthPress.com> © 2006 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.] KEYWORDS. Neurofeedback, EEG biofeedback, biofeedback, neurotherapy, LENS, low energy neurofeedback system, EEG, brain stimulation INTRODUCTION Evolution of LENS and Relevant Concepts The Low Energy Neurofeedback System The major implication of this paper is that (LENS) is an EEG biofeedback system used in both the physically and psychologically trau- clinical applications and research in the treat- matized brain has demonstrated vastly greater ment of central nervous system functioning. It capacity for recovery than has previously been is unique in the field of neurofeedback in that appreciated. Secondarily, the LENS appears to instead of only displaying information on a help the traumatized person achieve clearly in- computer screen to assist the patient in condi- creased performance in relatively short periods tioninghealthierbrainwavepatterns,theLENS of time, with a quite non-invasive, low technol- uses weak electromagnetic signals as a carrier ogy procedure. -

Internet of Nano-Things, Things and Everything: Future Growth Trends

future internet Review Internet of Nano-Things, Things and Everything: Future Growth Trends Mahdi H. Miraz 1 ID , Maaruf Ali 2, Peter S. Excell 3,* and Richard Picking 3 1 Centre for Financial Regulation and Economic Development (CFRED), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Sha Tin, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] 2 International Association of Educators and Researchers (IAER), Kemp House, 160 City Road, London EC1V 2NX, UK; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Art, Science and Technology, Wrexham Glyndwrˆ University, Wrexham LL11 2AW, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-797-480-6644 Received: 22 June 2018; Accepted: 25 July 2018; Published: 28 July 2018 Abstract: The current statuses and future promises of the Internet of Things (IoT), Internet of Everything (IoE) and Internet of Nano-Things (IoNT) are extensively reviewed and a summarized survey is presented. The analysis clearly distinguishes between IoT and IoE, which are wrongly considered to be the same by many commentators. After evaluating the current trends of advancement in the fields of IoT, IoE and IoNT, this paper identifies the 21 most significant current and future challenges as well as scenarios for the possible future expansion of their applications. Despite possible negative aspects of these developments, there are grounds for general optimism about the coming technologies. Certainly, many tedious tasks can be taken over by IoT devices. However, the dangers of criminal and other nefarious activities, plus those of hardware and software errors, pose major challenges that are a priority for further research. Major specific priority issues for research are identified. -

Ray Kurzweil Reader Pdf 6-20-03

Acknowledgements The essays in this collection were published on KurzweilAI.net during 2001-2003, and have benefited from the devoted efforts of the KurzweilAI.net editorial team. Our team includes Amara D. Angelica, editor; Nanda Barker-Hook, editorial projects manager; Sarah Black, associate editor; Emily Brown, editorial assistant; and Celia Black-Brooks, graphics design manager and vice president of business development. Also providing technical and administrative support to KurzweilAI.net are Ken Linde, systems manager; Matt Bridges, lead software developer; Aaron Kleiner, chief operating and financial officer; Zoux, sound engineer and music consultant; Toshi Hoo, video engineering and videography consultant; Denise Scutellaro, accounting manager; Joan Walsh, accounting supervisor; Maria Ellis, accounting assistant; and Don Gonson, strategic advisor. —Ray Kurzweil, Editor-in-Chief TABLE OF CONTENTS LIVING FOREVER 1 Is immortality coming in your lifetime? Medical Advances, genetic engineering, cell and tissue engineering, rational drug design and other advances offer tantalizing promises. This section will look at the possibilities. Human Body Version 2.0 3 In the coming decades, a radical upgrading of our body's physical and mental systems, already underway, will use nanobots to augment and ultimately replace our organs. We already know how to prevent most degenerative disease through nutrition and supplementation; this will be a bridge to the emerging biotechnology revolution, which in turn will be a bridge to the nanotechnology revolution. By 2030, reverse-engineering of the human brain will have been completed and nonbiological intelligence will merge with our biological brains. Human Cloning is the Least Interesting Application of Cloning Technology 14 Cloning is an extremely important technology—not for cloning humans but for life extension: therapeutic cloning of one's own organs, creating new tissues to replace defective tissues or organs, or replacing one's organs and tissues with their "young" telomere-extended replacements without surgery. -

Common Errors in Reasoning About the Future: Three Informal Fallacies

TFS-18563; No of Pages 9 Technological Forecasting & Social Change xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Technological Forecasting & Social Change From my perspective Common errors in reasoning about the future: Three informal fallacies Adam Dorr UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, Department of Urban Planning, 337 Charles E. Young Drive East, Los Angeles, CA 90095, United States article info abstract Article history: The continued exponential growth of the price-performance of computing is likely to effectuate technologies that Received 23 June 2015 radically transform both the global economy and the human condition over the course of this century. Conven- Received in revised form 11 April 2016 tional visions of the next 50 years fail to realistically account for the full implications of accelerating technological Accepted 14 June 2016 change driven by the exponential growth of computing, and as a result are deeply flawed. These flawed visions Available online xxxx are, in part, a consequence of three interrelated errors in reasoning: 1) the linear projection fallacy, 2) the ceteris paribus fallacy arrival fallacy Keywords: , and 3) the . Each of these informal fallacies is likely a manifestation of shortcomings Technological progress in our intuitions about complex dynamic systems. Recognizing these errors and identifying when and where they Accelerating change affect our own reasoning is an important first step toward thinking more realistically about the future. Computing © 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Fallacy Errors in reasoning 1. Introduction thoughtful consideration of the accelerating growth of computing shows that even the more radical of these technologies are likely to ar- Most professional, academic, and scientific disciplines hold unrealis- rive within just a few decades. -

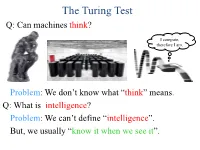

The Turing Test Q: Can Machines Think?

The Turing Test Q: Can machines think? I compute, therefore I am. Problem: We don’t know what ―think‖ means. Q: What is intelligence? Problem: We can’t define ―intelligence‖. But, we usually ―know it when we see it‖. The Turing Test Q: Which of the following can think? The Turing Test Q: Can you distinguish a machine from a person? ≡ Can a machine impersonate a person? The Turing Test • The first deep investigation into whether machines can ―behave intelligently‖ • Helped usher in field of AI • Decoupled ―intelligence‖ from ―human‖ • Based ―intelligence‖ on I/O, not entity’s ―look and feel‖ • Proposed a practical, formal test for intelligence • Definitions & test are operational & easily implementable • Turing test variants: ―immortality‖, ―fly-on-wall‖, ―meta‖, ―reverse‖, ―subject matter expert‖, ―compression‖, ―minimum intelligent signal‖ Turing Test Milestones Turk (von Kempelen), 1770: • Played a strong game of chess • Toured the world for 84 years • Generated much interest in automata • Was a hoax (hidden human operator) Turing Test Milestones Eliza (Weizenbaum), 1966: • First ―chatterbot‖ • Named after ―Eliza Doolittle‖ of Shaw’s Pygmalion • Simulated Rogerian psychotherapist • Often convinced people it is human • Influence computer games (e.g., Dungeon, Adventure) • Inspired Arthur C. Clarke’s HAL 9000 • Chatterbots appear today in chatrooms and dating services • Chatterbot competitions (Turing Test format): – Loebner Prize – Chatterbox Challenge, 2010 Turing Test Milestones Elbot, 2008: • Won 2008 Loebner Prize • Fooled 3 of 12 judges (Turing: >30%) • Typical excerpt: Judge: What's your favourite novel? Elbot: I often read telephone books, or dadaist poetry: Brä brä brä Judge: Typical computer! Elbot: You tend towards generalizations.