Limitations of the Embolic Hypothesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documentationand Coding Tips: Peripheral Vascular Disease

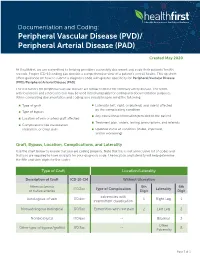

Documentation and Coding: Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD)/ Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) Created May 2020 At Healthfirst, we are committed to helping providers accurately document and code their patients’ health records. Proper ICD-10 coding can provide a comprehensive view of a patient’s overall health. This tip sheet offers guidance on how to submit a diagnosis code with greater specificity for Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD)/Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD). The risk factors for peripheral vascular disease are similar to those for coronary artery disease. The terms arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis may be used interchangeably for coding and documentation purposes. When completing documentation and coding, you should keep in mind the following: Type of graft Laterality (left, right, or bilateral) and side(s) affected by the complicating condition Type of bypass Any educational information provided to the patient Location of vein or artery graft affected Treatment plan, orders, testing, prescriptions, and referrals Complications like claudication, ulceration, or chest pain Updated status of condition (stable, improved, and/or worsening) Graft, Bypass, Location, Complications, and Laterality Use the chart below to ensure that you are coding properly. Note that this is not an inclusive list of codes and that you are required to have six digits for your diagnosis code. The location and laterality will help determine the fifth and sixth digits for the codes. Type of Graft Location/Laterality Description of Graft ICD-10-CM Without -

Venous Air Embolism, Result- Retrospective Study of Patients with Venous Or Arterial Ing in Prompt Hemodynamic Improvement

Ⅵ REVIEW ARTICLE David C. Warltier, M.D., Ph.D., Editor Anesthesiology 2007; 106:164–77 Copyright © 2006, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Diagnosis and Treatment of Vascular Air Embolism Marek A. Mirski, M.D., Ph.D.,* Abhijit Vijay Lele, M.D.,† Lunei Fitzsimmons, M.D.,† Thomas J. K. Toung, M.D.‡ exogenously delivered gas) from the operative field or This article has been selected for the Anesthesiology CME Program. After reading the article, go to http://www. other communication with the environment into the asahq.org/journal-cme to take the test and apply for Cate- venous or arterial vasculature, producing systemic ef- gory 1 credit. Complete instructions may be found in the fects. The true incidence of VAE may be never known, CME section at the back of this issue. much depending on the sensitivity of detection methods used during the procedure. In addition, many cases of Vascular air embolism is a potentially life-threatening event VAE are subclinical, resulting in no untoward outcome, that is now encountered routinely in the operating room and and thus go unreported. Historically, VAE is most often other patient care areas. The circumstances under which phy- associated with sitting position craniotomies (posterior sicians and nurses may encounter air embolism are no longer fossa). Although this surgical technique is a high-risk limited to neurosurgical procedures conducted in the “sitting procedure for air embolism, other recently described position” and occur in such diverse areas as the interventional radiology suite or laparoscopic surgical center. Advances in circumstances during both medical and surgical thera- monitoring devices coupled with an understanding of the peutics have further increased concern about this ad- pathophysiology of vascular air embolism will enable the phy- verse event. -

Spontaneous Hemothorax Caused by a Ruptured Intercostal Artery Aneurysm in Von Recklinghausen’S Neurofibromatosis

W.C. Chang, H.H. Hsu, H. Chang, et al BRIEF COMMUNICATION SPONTANEOUS HEMOTHORAX CAUSED BY A RUPTURED INTERCOSTAL ARTERY ANEURYSM IN VON RECKLINGHAUSEN’S NEUROFIBROMATOSIS Wei-Chou Chang,1 Hsian-He Hsu,1 Hung Chang,2 and Cheng-Yu Chen1 Abstract: Aneurysms arising from an intercostal artery are very rare vascular malformations in von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis, which often have a silent clinical presentation and are difficult to diagnose before rupture. We report a case of von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis with massive hemothroax caused by spontaneous rupture of an intercostal artery aneurysm in a 29-year-old man. The diagnosis was eventually confirmed by percutaneous angiography and treated with endovascular embolization. During a 10-month follow-up period, the patient had a satisfactory recovery. This case illustrates that angiography and possible endovascular embolization should be the first strategy in managing hemothorax in patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease. Key words: Aneurysm, ruptured; Embolization, therapeutic; Hemothorax; Neurofibromatosis 1; Thoracic arteries J Formos Med Assoc 2005;104:286-9 Von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis, also named neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), is a well-recognized Case Report entity that is characterized by numerous neuro- fibromas, spots of abnormal cutaneous pigmentation, A 29-year-old man presented at the emergency room and a variety of other dysplastic abnormalities of with sudden onset shortness of breath and severe the skin, nervous system, bones, endocrine organs and retrosternal pain radiating to his back. One week prior blood vessels.1,2 Vascular abnormalities in patients to admission, dull discomfort upon breathing was with NF-1 have been described for large, medium- noted, which was not affected by position or physical sized and small muscular arteries in the intracranial, activity. -

Hypertension: Putting the Pressure on the Silent Killer

HYPERTENSION: PUTTING THE PRESSURE ON THE SILENT KILLER MAY 2016 TABLEHypertension: putting OF the CONTENTS pressure on the silent killer Table of contents UNDERSTANDING HYPERTENSION AND THE LINK TO CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE 2 Understanding hypertension and the link to cardiovascular disease THEThe social SOCIAL and economic AND impact ECONOMIC of hypertension IMPACT OF HYPERTENSION 3 Diagnosing and treating hypertension – what is out there? DIAGNOSINGChallenges to tackling hypertension AND TREATING HYPERTENSION – WHAT IS OUT THERE? 6 Opportunities and focus areas for policymakers CHALLENGES TO TACKLING HYPERTENSION 9 OPPORTUNITIES AND FOCUS AREAS FOR POLICYMAKERS 15 HYPERTENSION: PUTTING THE PRESSURE ON THE SILENT KILLER UNDERSTANDING HYPERTENSION AND THE LINK TO CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE Cardiovascular disease (CVD), or heart disease, is the number one cause of death in the world. 80% of deaths due to CVD occur in countries and poor communities where health systems are weak, and CVD accounts for nearly half of the estimated US$500 billion annual lost economic output associated with noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) in low-income and middle-income countries. In 2012, CVD killed 17.5 million people – the equivalent of every 3 in 10 deaths.1 Of these 17 million deaths a year, over half – 9.4 million - are caused by complications in hypertension, also commonly referred to as raised or high blood pressure2. Hypertension is a risk factor for coronary heart disease and the single most important risk factor for stroke - it is responsible for at least 45% of deaths due to heart disease, and at least 51% of deaths due to stroke. High blood pressure is defined as a systolic blood pressure at or above 140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure at or above 90 mmHg. -

Pulmonary Embolism a Pulmonary Embolism Occurs When a Blood Clot Moves Through the Bloodstream and Becomes Lodged in a Blood Vessel in the Lungs

Pulmonary Embolism A pulmonary embolism occurs when a blood clot moves through the bloodstream and becomes lodged in a blood vessel in the lungs. This can make it hard for blood to pass through the lungs to get oxygen. Diagnosing a pulmonary embolism can be difficult because half of patients with a clot in the lungs have no symptoms. Others may experience shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness, and possibly swelling in the legs. If you have a pulmonary embolism, you need medical treatment right away to prevent a blood clot from blocking blood flow to the lungs and heart. Your doctor can confirm the presence of a pulmonary embolism with CT angiography, or a ventilation perfusion (V/Q) lung scan. Treatment typically includes medications to thin the blood or placement of a filter to prevent the movement of additional blood clots to the lungs. Rarely, drugs are used to dissolve the clot or a catheter-based procedure is done to remove or treat the clot directly. What is a pulmonary embolism? Blood can change from a free flowing fluid to a semi-solid gel (called a blood clot or thrombus) in a process known as coagulation. Coagulation is a normal process and necessary to stop bleeding and retain blood within the body's vessels if they are cut or injured. However, in some situations blood can abnormally clot (called a thrombosis) within the vessels of the body. In a condition called deep vein thrombosis, clots form in the deep veins of the body, usually in the legs. A blood clot that breaks free and travels through a blood vessel is called an embolism. -

Hypertension and Coronary Heart Disease

Journal of Human Hypertension (2002) 16 (Suppl 1), S61–S63 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9240/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/jhh Hypertension and coronary heart disease E Escobar University of Chile, Santiago, Chile The association of hypertension and coronary heart atherosclerosis, damage of arterial territories other than disease is a frequent one. There are several patho- the coronary one, and of the extension and severity of physiologic mechanisms which link both diseases. coronary artery involvement. It is important to empha- Hypertension induces endothelial dysfunction, exacer- sise that complications and mortality of patients suffer- bates the atherosclerotic process and it contributes to ing a myocardial infarction are greater in hypertensive make the atherosclerotic plaque more unstable. Left patients. Treatment should be aimed to achieve optimal ventricular hypertrophy, which is the usual complication values of blood pressure, and all the strategies to treat of hypertension, promotes a decrease of ‘coronary coronary heart disease should be considered on an indi- reserve’ and increases myocardial oxygen demand, vidual basis. both mechanisms contributing to myocardial ischaemia. Journal of Human Hypertension (2002) 16 (Suppl 1), S61– From a clinical point of view hypertensive patients S63. DOI: 10.1038/sj/jhh/1001345 should have a complete evaluation of risk factors for Keywords: hypertension; hypertrophy; coronary heart disease There is a strong and frequent association between arterial hypertension.8 Hypertension is frequently arterial hypertension and coronary heart disease associated to metabolic disorders, such as insulin (CHD). In the PROCAM study, in men between 40 resistance with hyperinsulinaemia and dyslipidae- and 66 years of age, the prevalence of hypertension mia, which are additional risk factors of atheroscler- in patients who had a myocardial infarction was osis.9 14/1000 men in a follow-up of 4 years. -

Pulmonary Embolism in the First Trimester of Pregnancy

Obstetrics & Gynecology International Journal Case Report Open Access Pulmonary embolism in the first trimester of pregnancy Summary Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2020 Pulmonary embolism in the first trimester of pregnancy without a known medical history Orfanoudaki Irene M is a very rare complication, which if it is misdiagnosed and left untreated leads to sudden Obstetric Gynecology, University of Crete, Greece pregnancy-related death. The sings and symptoms in this trimester are no specific. The causes for pulmonary embolism are multifactorial but in the first trimester of pregnancy, Correspondence: Orfanoudaki Irene M, Obstetric the most important causes are hereditary factors. Many times the pregnant woman ignores Gynecology, University of Crete, Greece, 22 Archiepiskopou her familiar hereditary history and her hemostatic system is progressively activated for the Makariou Str, 71202, Heraklion, Crete, Greece, Tel +30 hemostatic challenge of pregnancy and delivery. The hemostatic changes produce enhance 6945268822, +302810268822, Email coagulation and formation of micro-thrombi or thrombi and prompt diagnosis is crucial to prevent and treat pulmonary embolism saving the lives of a pregnant woman and her fetus. Received: January 19, 2020 | Published: January 28, 2020 Keywords: pregnancy, pulmonary embolism, mortality, diagnosis, risk factors, arterial blood gases, electrocardiogram, ventilation perfusion scan, computed tomography pulmonary angiogram, magnetic resonanance, compression ultrasonography, echocardiogram, D-dimers, troponin, brain -

Hypertension, Cholesterol, and Aspirin with Cost Info

Diabetes & Your Health High Blood Pressure & Diabetes Aspirin & Did you know as many as two out of three adults with Heart Health diabetes have high blood pressure? High blood pressure Studies have shown is a serious problem. It can raise your chances of stroke, that taking a low- heart attack, eye problems, and kidney disease. dose aspirin every Many people do not know they have high blood pressure day can lower the because they do not have any symptoms. That is why it risk for heart attack is often called “the silent killer.” and stroke. The only way to know if you have high blood pressure is Aspirin can help to have it checked. If you have diabetes, you should those who are at high have your blood pressure checked every time you see risk of heart attack, the doctor. People with diabetes should try to keep their such as people who blood pressure lower than 130 over 80. have diabetes or high blood pressure. Cholesterol & Diabetes Aspirin can also help Keeping your cholesterol and other blood fats, called lipids, under control can people with diabetes help you prevent diabetes problems. Cholesterol and blood lipids that are too who have already high can lead to heart attack and stroke. Many people with diabetes have had a heart attack or problems with their cholesterol and other lipid levels. a stroke, or who have heart disease. You will not know that your cholesterol and blood lipids are at dangerous levels unless you have a blood test to have them checked. Everyone with diabetes Taking an aspirin a should have cholesterol and other lipid levels checked at least once per year. -

Major Clinical Considerations for Secondary Hypertension And

& Experim l e ca n i t in a l l C Journal of Clinical and Experimental C f a o r d l i a o Thevenard et al., J Clin Exp Cardiolog 2018, 9:11 n l o r g u y o Cardiology DOI: 10.4172/2155-9880.1000616 J ISSN: 2155-9880 Review Article Open Access Major Clinical Considerations for Secondary Hypertension and Treatment Challenges: Systematic Review Gabriela Thevenard1, Nathalia Bordin Dal-Prá1 and Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho2* 1Santa Casa de Misericordia Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil 2Department of scientific production, Street Ipiranga, São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil *Corresponding author: Idiberto José Zotarelli Filho, Department of scientific production, Street Ipiranga, São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil, Tel: +5517981666537; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: October 30, 2018; Accepted date: November 23, 2018; Published date: November 30, 2018 Copyright: ©2018 Thevenard G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Introduction: In this context, secondary arterial hypertension (SH) is defined as an increase in systemic arterial pressure (SAP) due to an identifiable cause. Only 5 to 10% of patients suffering from hypertension have a secondary form, while the vast majorities have essential hypertension. Objective: This study aimed to describe, through a systematic review, the main considerations on secondary hypertension, presenting its clinical data and main causes, as well as presenting the types of treatments according to the literary results. -

Association Between Multi-Site Atherosclerotic Plaques and Systemic Arteriosclerosis

Association between multi-site atherosclerotic plaques and systemic arteriosclerosis: results from the BEST study (Beijing Vascular Disease Patients Evaluation Study) huan liu Peking University Shougang Hospital https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6223-7677 Jinbo Liu Peking University Shougang Hospital Wei Huang Peking University Shougang Hospital Hongwei Zhao Peking University Shougang Hospital Na zhao Peking University Shougang Hospital Hongyu wang ( [email protected] ) Research Keywords: arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis, atherosclerotic plaque, carotid femoral artery pulse wave velocity CF-PWV Posted Date: June 8th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-31641/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on August 1st, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12947-020-00212-3. Page 1/18 Abstract Background Arteriosclerosis can be reected in various aspect of the artery, including atherosclerotic plaque formation or stiffening on the arterial wall. Both arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis are important and closely associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD). The aim of the study was to evaluate the association between systemic arteriosclerosis and multi-site atherosclerotic plaques. Methods The study was designed as an observational cross-sectional study. A total of 1178 participants (mean age 67.4 years; 52.2% male) enrolled into the observational study from 2010 to 2017. Systemic arteriosclerosis was assessed by carotid femoral artery pulse wave velocity (CF-PWV) and multi-site atherosclerotic plaques (MAP, >=2 of the below sites) were reected in the carotid or subclavian artery, abdominal aorta and lower extremities arteries using ultrasound equipment. -

Pulmonary Embolism

Pulmonary Embolism Pulmonary Embolism (PE) is the blockage of one or more arteries in the lungs, ultimately eliminating the oxygen supply causing heart failure. This can take place when a blood clot from another area of the body, most often from the legs, breaks free, enters the blood stream and gets trapped in the lung's arteries. Once a clot is lodged in the artery of the lung, the tissue is then starved of fuel and may die (pulmonary infarct) or the blockage of blood flow may result in increased strain on the right side of the heart. It is estimated that approximately 600,000 patients suffer from pulmonary embolism each year in the US. Of these 600,000, 1/3 will die as a result. Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) is the most common precursor of pulmonary embolism. With early treatment of DVT, patients can reduce their chances of developing a life threatening pulmonary embolism to less than one percent. Early treatment with blood thinners is important to prevent a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, but does not treat the existing clot in the leg. Get more information on Deep Vein Thrombosis. Symptoms of PE Symptoms of pulmonary embolism can include shortness of breath; rapid pulse; sweating; sharp chest pain; bloody sputum (coughing up blood); and fainting. These symptoms are frequently nonspecific to pulmonary embolism and can mimic other cardiopulmonary events. Since pulmonary embolism can be life-threatening, if any of these symptoms are present please see your physician immediately. Treatments for PE Anticoagulation The first line of defense when treating pulmonary embolism is by using an anticoagulant. -

Pulmonary Hypertension ______

Pulmonary Hypertension _________________________________________ What is it? High blood pressure in the arteries that supply the lungs is called pulmonary hypertension (PH) or pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). The blood pressure measured by a cuff on your arm isn’t directly related to the pressure in your lungs. The blood vessels that supply the lungs constrict and their walls thicken, so they can’t carry as much blood. As in a kinked garden hose, pressure builds up and backs up. The heart works harder, trying to force the blood through. If the pressure is high enough, eventually the heart can’t keep up, and less blood can circulate through the lungs to pick up oxygen. Patients then become tired, dizzy and short of breath. If a pre-existing disease triggered the PH, doctors call it secondary pulmonary hypertension. That’s because it’s secondary to another problem, such as a left heart or lung disorder. However, congenital heart disease can cause PH that’s similar to PH when the cause isn’t known, i.e., idiopathic or unexplained pulmonary arterial hypertension. In this case, the PAH is considered pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease, such as associated with a VSD or ASD (either repaired or unrepaired). The problem is due to scarring in the small arteries in the lung. It’s important to repair congenital heart problems (when possible) before permanent pulmonary hypertensive changes develop. Intracardiac left-to-right shunts (such as a ventricular or atrial septal defect, a hole in the wall between the two ventricles or atria) can cause too much blood flow through the lungs.