Whether During the Height of Elizabeth I's Reign, Or in Our Own Time, The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Download Booklet

Royal Rhymes and Rounds ELIZABETH II Choral Dances from “Gloriana” Benjamin Britten u Time [1.51] i Concord [2.25] HENRY VIII o Time and Concord [1.46] 1 Pastime with good companie (The King’s Ballad) King Henry VIII [1.53] p Country Girls [1.17] 2 Ah, Robin, gentle Robin William Cornysh [2.26] a Rustics and Fishermen [1.00] 3 Blow thy horn, hunter William Cornysh [2.23] s Final Dance of Homage [2.20] 4 King Henry VIII [1.33] It is to me a right great joy d A Rough Guide to the Royal Succession Paul Drayton [12.48] 5 Anonymous [3.56] Hey, trolly lolly lo! (It’s just one damn King after another…) ELIZABETH I Total timings: [65.50] 6 Long live, fair Oriana Ellis Gibbons [2.39] 7 The Silver Swan (Round) Orlando Gibbons [2.00] THE KING’S SINGERS 8 The Silver Swan Orlando Gibbons [1.46] 9 Fair Oriana, beauty’s Queen John Hilton [2.21] www.signumrecords.com 0 Lightly she whipped o’er the dales John Mundy [3.11] q Flow, O my tears John Dowland [1.37] ROYAL RHYMES AND ROUNDS w Weep, O mine eyes John Bennet [2.44] medieval times to the prestigious position of e As Vesta was from Latmos hill descending Thomas Weelkes [3.19] There is little doubt that the development of ‘Master of the Queen’s Music’, currently held by Western classical music over the centuries owes Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (b.1934). In this VICTORIA a great deal to the patronage of kings and Diamond Jubilee year, as we mark the 60th r The Triumph of Victoria Sir Walter Parratt [2.33] queens. -

The Byrd Edition & English Madrigalists

T74 (2020) THE BYRD EDITION and THE ENGLISH MADRIGALISTS (including the INVITATION Series) William Byrd 1543 — 1623 STAINER & BELL ORDERING INFORMATION This catalogue contains titles in print at the date of its preparation and provides details of volumes in The Byrd Edition, The English Madrigalists and the Invitation Series. A brief description of contents is given and full lists of contents may be obtained by quoting the CON or ASK sheet number given. Many items by William Byrd and composers included in The English Madrigalists are available as separate items and full details can be found in our Choral Catalogue (T60) and our Early Music Catalogue (T71). Items not available either separately or in a small anthology may be obtained through our ‘Made-to-Order’ Service. Our Archive Department will be pleased to help with enquiries and requests. Alternatively, Adobe Acrobat PDF files of individual titles from The Byrd Edition and The English Madrigalists are now available through the secure Stainer & Bell online shop. Please see pages 5 and 13 for full details. Other catalogues containing our library series which will be of interest are: T69 Musica Britannica T75 Early English Church Music T108 Purcell Society Edition Prices, shown in £ sterling, are recommended retail prices exclusive of carriage and are applicable from 1st January 2020. Prices and carriage charges are subject to change without notice. In case of difficulty titles can be supplied directly by the publisher if prepaid by cheque, debit or credit card or by sending an official requisition. Card payments (Visa, Mastercard, Maestro or Visa Debit) are accepted for orders of £5.00 or over and can be made via our secure online ordering system on our website (www.stainer.co.uk) or by letter, telephone, email or fax. -

Fall 2010 Collegium Program Notes

Program Notes It is with great pleasure that we welcome you to tonight’s celebration of music’s patron saint, Cecilia, on November 22, her name day. As international as FIU’s middle name, this concert is a French and English tribute to a 5th-century Italian martyr. Our program praises noble women: Susanne, the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Machaut Messe and Charpentier Noëls, Queen Elizabeth in the English Madrigals, and Cecilia herself in Purcell’s Welcome To All The Pleasures. Throughout the concert, we will be displaying a slideshow that presents images related to Cecilia, her shrine in Rome, and the music we will be performing. Tonight we introduce the versatile and lovely chamber continuo organ commissioned for us with funds provided by Herbert and Nicole Wertheim. This evening also marks the first performance on viols from Collegium’s most recent donation, the McClure Collection of Student Viols. Renaissance music abounds in settings by different composers of popular tunes: “L’Homme Armé,” “Lachryme,” Douce Memoire,” and many others, including “Susanne un jour,” first known in the 4-part setting by Didier Lupi II of a text by Guilliaume Gueroult published in 1548. In tonight’s program we hear just a few of the more than 30 versions of this melody and text: a solo song in French; an ornamented lute dance; the dance arranged for 5 instruments plus lute; an instrumental version of a madrigal setting by Lasso—who also wrote an entire 6-part Mass based on the tune; and an English part-song by William Byrd for soprano voice and four viols. -

Sister, Awake! Author(S): Thomas Bateson Source: the Musical Times, Vol

Extra Supplement: Sister, Awake! Author(s): Thomas Bateson Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 47, No. 755 (Jan. 1, 1906), pp. 1-8 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/904216 Accessed: 18-01-2016 13:26 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 144.122.201.150 on Mon, 18 Jan 2016 13:26:43 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TheMusical Times, EXTRASUPPLEMENT. January1,196. No. 42. SISTER, AWAKE !-ThomasBateson. Price3d. THE ORIANA COLLECTION OF EARLY MADRIGALS BRITISH AND FOREIGN. ** The firsttwenty-five numbers of the collectionwill consistof a re-edition(by Mr. Lionel Benson) of The Triumphsof Oriana, firstpublished in London by Thomas Morley,x6oi. Nos. 26-29were apparently composedfor the same series,but werenot includedin the firstedition. YOU DAZZLE BUT THE SIGHT ... MICHAELESTE z. HENCE, STARS, (5 voices) 3d. 2. ... DANIEL WITH ANGEL'SFACE AND BRIGHTNESS... ( ,, ) NORCOME3d. 3. LIGHTLY SHE TRIPPED O'ER THE DALES ( ,, )... JOHNMUNDY 4d. 4. -

Download Booklet

082Booklet 28/9/06 22:06 Page 1 ALSO on signumclassics Gesualdo: 1605 Treason and Dischord Sacred Bridges Tenebrae Responsories for Maundy Thursday The King’s Singers, Concordia SIGCD061 The King’s Singers, Sarband SIGCD065 The King’s Singers SIGCD048 The 15th century Prince Carlo Gesualdo – nobleman, Commemorating the 400th anniversary of the The radiant voices of the King’s Singers and the composer and notorious murderer – wrote some Gunpowder Plot, the King’s Singers and Concordia exotic sounds of Sarband unite in a celebration of the of the most expressive and sensual music of the illuminate Mass sung in secret and worshippers rich connections between the Orient and Occident, Neapolitan school. This programme represents risking their lives for their faith. The music is a musical exploration of the sacred bridges part of the liturgy for the Matins Offices on the structured around Byrd’s near perfect Four Part between Christianity, Islam and Judaism as seen final three days of Holy Week, the Triduum Sacrum. Mass, and contains motets by Catholic composers through settings of the timeless Psalms of David. balanced with Protestant anthems celebrating “The teamwork of the ensemble is stunningly the downfall of the Plot, together with a commission “immaculate blend, perfect tuning and crystal good, the tuning impeccable, and the dynamic from Francis Pott. diction ... Superb performances across the range enormous.” John Milsom - Early Music cultural divide show that great art transcends “…this is a serious project, which, like the political differences. May thine enemy buy it also” plotters themselves, has been skilfully executed. The Times (UK) Strongly recommended.” International Record Review www.signumrecords.com www.kingssingers.com Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 082Booklet 28/9/06 22:06 Page 3 the triumphs of oriana the triumphs of oriana The Triumphs of Oriana is an Elizabethan curiosity, the swan contributor. -

The Madrigal

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1-1930 The madrigal. Frank B. Martin University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Frank B., "The madrigal." (1930). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 910. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/910 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'I UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE THE MADRIGAL. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty Of the Graduate School Of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts Department of English By FRANK B. lVlARTIN 1930 CONTENTS Chapter-. Pages. I The Foreign Madrigal 1 - 9. Ii II The English Madrigal 10 - 21. "i'" III The Etymology and structure 22 - 27. IV The Lyrics 28 - 41. V Composers 42 - 59. VI Recent Tendencies 60 - 64. Conclusions 65 - 67. .. Example of a-Madrigal 68 - 76. ~ Bibliography 77 - 79. .~ • • • THE FORKEGN MADR IGAL • • , CHAPTER I · . THE FOREIGN MADRIGAL The madrigal is the oldest of concerted • secular forms. It had its origin in northern Ita17, perhaps as early as the twelfth century. The early ..."i;'" compositions had none of the elaborate devices which characterize the madrigals of the sixteenth century. -

Thomas Morley and the Business of Music in Elizabethan England

THOMAS MORLEY AND THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC IN ELIZABETHAN ENGLAND by TERESA ANN MURRAY A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Thomas Morley’s family background in Norwich and his later life in London placed him amongst the educated, urban, middle classes. Rising literacy and improving standards of living in English cities helped to develop a society in which amateur music-making became a significant leisure activity, providing a market of consumers for printed recreational music. His visit to the Low Countries in 1591 allowed him to see at first hand a thriving music printing business. Two years later he set out to achieve an income from his own music, initially by publishing collections of light, English-texted, madrigalian vocal works. He broadened his activities by obtaining a monopoly for printed music in 1598 and then by entering into a partnership with William Barley to print music. -

Morley, Thomas

Thomas Morley (b. 1557 or 1558, Norwich, England; d. 1602, London) Thomas Morley was a composer, theorist, editor, and organist and is considered by many to have been the Foremost composer oF the English Madrigal School. A pupil oF William Byrd, Morley dedicated his theoretical work A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicalle Musicke (1597)—the most celebrated English treatise oF the Renaissance—to his master. Morley was appointed Master oF Choristers at Norwich Cathedral in 1583. He received a Bachelor oF Music degree From OxFord University in 1588, became organist oF St. Paul’s Cathedral the Following year, and was appointed Gentleman oF the Chapel Royal in 1592. In 1598, Queen Elizabeth granted him exclusive license to print and sell music in England. Morley’s principal contribution to music history was in the Form oF the madrigal, publishing 11 collections oF madrigals during his liFetime. His work displays a wide range oF emotional color, Form, and technique. Many oF his madrigals are light, Fast, and highly singable. His Canzonets for Five and Six Voices, however, reveal sad as well as cheerFul moods, representing his mature style. A Few oF his most popular madrigals are “Aprill Is in My Mistris Face,” “My Bonny Lasse Shee Smyleth,” “Now Is the Month oF Maying,” and “Sing We and Chant it.” In 1601, Morley edited the Triumphs of Oriana, a collection oF 25 madrigals by 23 composers compiled to honor Queen Elizabeth I—sometimes reFerred to in poetry as “Orianna.” In addition to his madrigals, Morley wrote ballets; music For the liturgy oF the Church oF England, including service and psalm settings and motets; keyboard music, some oF which has been preserved in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book; music For lute; and music For consorts oF instruments Favored in England at the time. -

4816616-434E69-Sigcd307booklet

Royal Rhymes and Rounds ELIZABETH II Choral Dances from “Gloriana” Benjamin Britten u Time [1.51] i Concord [2.25] HENRY VIII o Time and Concord [1.46] 1 Pastime with good companie (The King’s Ballad) King Henry VIII [1.53] p Country Girls [1.17] 2 Ah, Robin, gentle Robin William Cornysh [2.26] a Rustics and Fishermen [1.00] 3 Blow thy horn, hunter William Cornysh [2.23] s Final Dance of Homage [2.20] 4 King Henry VIII [1.33] It is to me a right great joy d A Rough Guide to the Royal Succession Paul Drayton [12.48] 5 Anonymous [3.56] Hey, trolly lolly lo! (It’s just one damn King after another…) ELIZABETH I Total timings: [65.50] 6 Long live, fair Oriana Ellis Gibbons [2.39] 7 The Silver Swan (Round) Orlando Gibbons [2.00] THE KING’S SINGERS 8 The Silver Swan Orlando Gibbons [1.46] 9 Fair Oriana, beauty’s Queen John Hilton [2.21] www.signumrecords.com 0 Lightly she whipped o’er the dales John Mundy [3.11] q Flow, O my tears John Dowland [1.37] ROYAL RHYMES AND ROUNDS w Weep, O mine eyes John Bennet [2.44] medieval times to the prestigious position of e As Vesta was from Latmos hill descending Thomas Weelkes [3.19] There is little doubt that the development of ‘Master of the Queen’s Music’, currently held by Western classical music over the centuries owes Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (b.1934). In this VICTORIA a great deal to the patronage of kings and Diamond Jubilee year, as we mark the 60th r The Triumph of Victoria Sir Walter Parratt [2.33] queens. -

288352408.Pdf

THOMAS EAST MUSIC PRINTER , 1588-1608 by Alan B. Mitchell A Master's Dissertation, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Science degree of the Loughborough University of Technology. September 1984 Supervisor: John Feather Department of Library and Information Studies lQu;h~:,-:;:t ~)'1~h UAlw.,.,rt, of T ',< ,;";"~CI~'Y Ubr~ry r:::-:-:-, .'''-' .-'-,',-- ' '-::~_NPY r '6 If... j{'hn r~:C OO'5"'3t5irOI CON TEN T S Acknowledgements iii List of Facsimiles iv Facsimiles v 1 Thomas East, Stationer 1 2 Part Books 18 3 Psalm Books 26 4 Tablature Books 32 5 Archival Material 40 a) Calendar of East's activities as a printer 41 b) Documents concerning the music patents 45 c) Freeman and Apprentices of East 56 d) Music books entered to East in the Stationers' Register 58 e) Books assigned to other printers following East's death 64 6 Bibliographical Catalogue 67 a) Chronological Listing 68 b) Alphabetical Listing 71 c) Statistics on Music Printing 90 Notes Bibliography 1 03 ---------------- -- -- iii Acknowledgements The inspiration for this historical study came originally from Professor lan Bent and Dr John Morehen who between them first aroused my interest in the development of printing. Thanks are due to them and to my present supervisor Hr John Feather for the infectious enthusiasm they impart to the study of bibliography. To be able to fulfil a piece of original research based on primary source materials I have become deeply indebted to the staff of the libraries in which I have worked, in particular the British Library, the Bodleian Library, the John Rylands University Library of Manchester and the Manchester Public Library. -

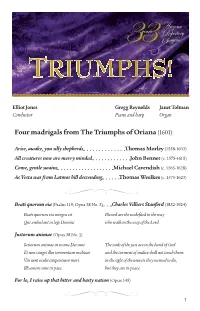

ARS-Triumphs-Program-Notes

TRIUMPHS! Elliot Jones Gregg Reynolds Janet Tolman Conductor Piano and harp Organ Four madrigals from The Triumphs of Oriana (1601): Arise, awake, you silly shepherds Thomas Morley (1558-1603) All creatures now are merry minded John Bennet (c. 1575-1615) Come, gentle swains Michael Cavendish (c. 1565-1628) As Vesta was from Latmos hill descending Thomas Weelkes (c. 1575-1623) Beati quorum via (Psalm 119; Opus 38 No. 3) Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) Beati quorum via integra est Blessed are the undefiled in the way Qui ambulant in lege Domini who walk in the way of the Lord. Justorum animae (Opus 38 No. 1) Justorum animae in manu Dei sunt The souls of the just are in the hand of God Et non tanget illos tormentum malitiae and the torment of malice shall not touch them: Visi sunt oculis insipentium mori in the sight of the unwise they seemed to die, Illi autem sunt in pace. but they are in peace. For lo, I raise up that bitter and hasty nation (Opus 145) 1 Quam pulchra es John Dunstable (c. 1390-1453) Quam pulchra es et quam decora How beautiful you are, and how graceful, Carissima in deliciis. dearest one, my delight. Statura tua assimilata est palme Your stature is like a palm tree Et ubera tua botris. and your breasts like clusters of grapes. Caput tuum ut Carmelus Your head is like Carmel Collum tuum sicut turris eburnea. and your neck like an ivory tower. Veni, dilecte mi, Come, my beloved, Egrediamur in agrum let us go into the fields Et videamus si flores fructus parturierunt and see if the grapes have borne fruit, Si floruerunt mala Punica.