'Telling the Truth About People's China'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adapting to Institutional Change in New Zealand Politics

21. Taming Leadership? Adapting to Institutional Change in New Zealand Politics Raymond Miller Introduction Studies of political leadership typically place great stress on the importance of individual character. The personal qualities looked for in a New Zealand or Australian leader include strong and decisive action, empathy and an ability to both reflect the country's egalitarian traditions and contribute to a growing sense of nationhood. The impetus to transform leaders from extraordinary people into ordinary citizens has its roots in the populist belief that leaders should be accessible and reflect the values and lifestyle of the average voter. This fascination with individual character helps account for the sizeable biographical literature on past and present leaders, especially prime ministers. Typically, such studies pay close attention to the impact of upbringing, personality and performance on leadership success or failure. Despite similarities between New Zealand and Australia in the personal qualities required of a successful leader, leadership in the two countries is a product of very different constitutional and institutional traditions. While the overall trend has been in the direction of a strengthening of prime ministerial leadership, Australia's federal structure of government allows for a diffusion of leadership across multiple sources of influence and power, including a network of state legislatures and executives. New Zealand, in contrast, lacks a written constitution, an upper house, or the devolution of power to state or local government. As a result, successive New Zealand prime ministers and their cabinets have been able to exercise singular power. This chapter will consider the impact of recent institutional change on the nature of political leadership in New Zealand, focusing on the extent to which leadership practices have been modified or tamed by three developments: the transition from a two-party to a multi-party parliament, the advent of coalition government, and the emergence of a multi-party cartel. -

Bromley Cemetery Guide

Bromley Cemetery Tour Compiled by Richard L. N. Greenaway June 2007 Block 1A Row C No. 33 Hurd Born at Hinton, England, Frank James Hurd emigrated with his parents. He worked as a contractor and, in 1896, in Wellington, married Lizzie Coker. The bride, 70, claimed to be 51 while the groom, 40, gave his age as 47. Lizzie had emigrated on the Regina in 1859 with her cousin, James Gapes (later Mayor of Christchurch) and his family and had already been twice-wed. Indeed, the property she had inherited from her first husband, George Allen, had enabled her second spouse, John Etherden Coker, to build the Manchester Street hotel which bears his name. Lizzie and Frank were able to make trips to England and to Canada where there dwelt Lizzie’s brother, once a member of the Horse Guards. Lizzie died in 1910 and, two years later, Hurd married again. He and his wife lived at 630 Barbadoes Street. Hurd was a big man who, in old age he had a white moustache, cap and walking stick. He died, at 85, on 1 April 1942. Provisions of Lizzie’s will meant that a sum of money now came to the descendants of James Gapes. They were now so numerous that the women of the tribe could spend their inheritance on a new hat and have nothing left over. Block 2 Row B No. 406 Brodrick Thomas Noel Brodrick – known as Noel - was born in London on 25 December 1855. In 1860 the Brodricks emigrated on the Nimrod. As assistant to Canterbury’s chief surveyor, J. -

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

READING REVOLUTION Thomas Fisher University Rare of Book Toronto Library, Art and Literacy During China’S Cultural Revolution

READING REVOLUTION READING REVOLUTION Art and Literacy during China’s Cultural Revolution HannoSilk 112pg spine= .32 Art and LiteracyCultural Revolution during China’s UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY, 2016 $20.00 Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto Reading Revolution: Art and Literacy during China’s Cultural Revolution Exhibition and catalogue by Jennifer Purtle and Elizabeth Ridolfo with the contribution of Stephen Qiao Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto 21 June – 30 September 2016 Catalogue and exhibition by Jennifer Purtle, Elizabeth Ridolfo, and Stephen Qiao General editors P.J. Carefoote and Philip Oldfield Exhibition installed by Linda Joy Digital photography by Paul Armstrong Catalogue printed by Coach House Press Permission for the use of Toronto Star copyright photographs by Mark Gayn and Suzanne Gayn, held in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, courtesy Torstar Syndication Services. library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Purtle, Jennifer, 1966-, author, organizer Reading revolution : art and literacy during China’s Cultural Revolution / exhibition and catalogue by Jennifer Purtle, Stephen Qiao, and Elizabeth Ridolfo. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-7727-6119-4 (paperback) 1. Mao, Zedong, 1893-1976—Bibliography—Exhibitions. 2. Literacy— China—History—20th century—Exhibitions. 3. Chinese—Books and reading— History—20th century—Exhibitions. 4. Books and reading—China—History— 20th century—Exhibitions. 5. Propaganda, Communist—China—History— 20th century—Exhibitions. 6. Propaganda, Chinese—History—20th century— Exhibitions. 7. Political posters, Chinese—History—20th century—Exhibitions. 8. Art, Chinese—20th century—Exhibitions. 9. China—History—Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976—Art and the revolution—Exhibitions. 10. China— History—Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976—Propaganda—Exhibitions. -

Struggle, #120, March 2006

STRUGGLE A MARXIST APPROACH TO AOTEAROA/NEW ZEALAND No: 120 : $1.50 : March 2006 Super-size My Pay Mobilise to End Youth Rates and Demand $12 Minimum Now In the face of widespread demands for an they rose by 28.8% in Australia, 39.5% end to age poverty, the Clark regime’s cob- in Canada, 46.9% in UK and 68.2% bled coalition has said it wants to raise the Finland. minimum wage to $12.00 per hour by the end of 2008 if ‘economic conditions per- • During the same two decades corporate mit’. But 2008 is too late for low paid and profits went from 34% of GDP to 46%. minimum wage workers - there is already a Wages as a share of GDP fell from 57% low wage crisis despite recent growth in the 42%. economy and record corporate profits. • Australian average wages are 30% high- The Unite union reports that tens of thou- er than NZ now when they were the sands of workers live on the current mini- same as NZ twenty years ago mum wage of $9.50 an hour for those 18 and older and $7.60 an hour for 16 and 17 Poverty-wages are increasing the gap year olds. There is no minimum wage for between rich and poor and increasing other those 15 and under. social inequalities. The majority of low paid and minimum wage workers are women, Compare that to Australia where the mini- Maori, pacific nation peoples, disabled, mum wage is $NZ13.85, nearly 50% higher youth, students and new migrants. -

Women of the Polynesian Panthers by Ruth Busch

Auckland Women's Centre AUTUMN ISSUE QUARTERLY 2016 IN THIS 01 Women of the 02 New Young Women’s 03 Stellar Feminist 04 SKIP Community ISSUE: Polynesian Panthers Coordinator, line-up at the Garden Opening Māngere East Writers Festival AND MORE Women of the Polynesian Panthers By Ruth Busch A wonderful evening (also empowering, stimulating and reflective to list just a few more superlatives to describe this event) took place at the Auckland Women’s Centre on the 23rd of March. As a follow-up to the previous Sunday’s fundraiser documentary about the Black Panther Party in the US, the Centre organised a panel discussion focussing on Women in the Polynesian Panthers and their Legacy. It was facilitated by Papatuanuku Nahi who welcomed the jam packed, mostly women, audience with a karanga that set the mood for the evening. The speakers’ panel was made up of Panther members, Miriama Rauhihi Ness and Dr Melani Anae, or (like our facilitator, Papatuanuku Nahi and her sister, Kaile Nahi- Taihia) women who traced their current activism directly to being raised by Panther parents. Sina Brown-Davis, Te Wharepora Hou member, and our speaker prior to the documentary screening, was also a panel member. Pictured: Sina Brown-Davis The speakers discussed racism and other More than that, that activism was the answer. Pacific abuses that had led them to form/join the Island and Maori communities could not wait for the government to come up with answers to homelessness, Panthers in the 1970s, their numerous poverty, police harassment and enforced incarceration. successes and the issues remaining to be The Dawn Raids in 1976 underscored both the systemic addressed still/now. -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949. -

Important Factors Affecting Customers in Buying Japanese Vehicles in New Zealand: a Case Study

Important factors affecting customers in buying Japanese vehicles in New Zealand: A case study Henry Wai Leong Ho, Ferris State University, Big Rapids, MI, USA Julia Sze Wing Yu, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia Abstract Just like many developed countries, car ownership in New Zealand (NZ) is an important determinant of household travel behavior. New Zealanders like buying used cars (mainly direct import from Japan) due to their affordability and reputation of good condition of the Japanese car. It has been mentioned for many years that Chinese ethnic group is not only one of the largest immigrants in NZ but also one of the most attractive customer groups in NZ market. This research aims to identify what are the NZ Chinese customers’ preferences and perceptions in purchasing Japanese used vehicles and how the used car dealers in NZ can successfully attract and convince their Chinese customers to purchase from them. Based on the survey results, Chinese customers agreed that price, fuel efficiency as well as style and appearance are all the important factors when they decide which Japanese vehicles to buy. Other than that, used car dealers with good reputation as well as friends and family recommendations are also some of the important factors for Chinese customers in helping them to select the right seller to purchase their Japanese used vehicles. Keywords: Chinese migrants in New Zealand; Japanese used car; used car dealer in New Zealand; customer perception; automobile industry Bibliography 1st and corresponding author: Henry W. L. Ho, MBus (Marketing), DBA Dr. Henry Ho is an Associate Professor of Marketing at Ferris State University in Michigan, USA. -

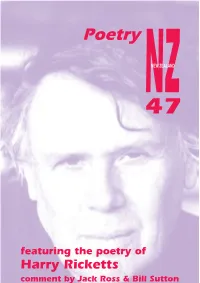

PNZ 47 Digital Version

Poetry NZNEW ZEALAND 47 featuring the poetry of 1 Harry Ricketts comment by Jack Ross & Bill Sutton Poetry NZ Number 47, 2013 Two issues per year Editor: Alistair Paterson ONZM Submissions: Submit at any time with a stamped, self-addressed envelope (and an email address if available) to: Poetry NZ, 34B Methuen Road, Avondale, Auckland 0600, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo El Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Please note that overseas submissions cannot be returned, and should include an email address for reply. Postal subscriptions: Poetry NZ, 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand or 1040 E. Paseo el Mirador, Palm Springs, CA 92262-4837, USA Postal subscription Rates: US Subscribers (by air) One year (2 issues) $30.00 $US24.00 Two years (4 issues) $55.00 $US45.00 Libraries: 1 year $32.00 $US25.00 Libraries: 2 years $60.00 $US46.00 Other countries One year (2 issues) $NZ36.00 Two years (4 issues) $NZ67.00 Online subscriptions: To take out a subscription go to www.poetrynz.net and click on ‘subscribe’. The online rates are listed on this site. When your subscription application is received it will be confi rmed by email, and your fi rst copy of the magazine will then be promptly posted out to you. 2 Poetry NZ 47 Alistair Paterson Editor Puriri Press & Brick Row Auckland, New Zealand Palm Springs, California, USA September 2013 3 ISSN 0114-5770 Copyright © 2013 Poetry NZ 37 Margot Street, Epsom, Auckland 1051, New Zealand All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the publisher. -

Shilliam, Robbie. "The Rise and Fall of Political Blackness." the Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "The Rise and Fall of Political Blackness." The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 51–70. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-003>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 05:59 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The Rise and Fall of Political Blackness Introduction Blackness was a mode of being that Black Power activists in the USA sought to recover and sanctify in order to confront a viscerally and institutionally racist settler state. In this chapter we examine the political identifications with Blackness that emerged in another racist settler state – New Zealand. In pursuit of restitution for colonial injus- tices, the identification with Blackness provided for a deeper binding between the children of Tāne/Māui and Legba. Along with Māori we must now add to this journey their tuākana (elder siblings), the Pasifika peoples – especially those from islands that the New Zealand state enjoyed some prior imperial relationship with – who had also arrived in urban areas in increasing numbers during the 1960s. In this chapter, we shall first witness how young Pasifika activists learnt similar lessons to their Māori cousins in Ngā Tamatoa regarding Black Power, yet cultivated, through the activities of the Polynesian Panthers, a closer political identification with Blackness. We shall then turn to the high point of confrontation during this period, the anti-Apartheid resistance to the tour by the South African Springboks rugby team in 1981. -

New Zealanders on the Net Discourses of National Identities In

New Zealanders on the Net Discourses of National Identities in Cyberspace Philippa Karen Smith A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2012 Institute of Culture, Discourse & Communication School of Language and Culture ii Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... v List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ vi Attestation of Authorship ......................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... ix Chapter One : Identifying the problem: a ‘new’ identity for New Zealanders? ................... 1 1.1 Setting the context ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 New Zealand in a globalised world .................................................................................................... -

"Thought Reform" in China| Political Education for Political Change

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1979 "Thought reform" in China| Political education for political change Mary Herak The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Herak, Mary, ""Thought reform" in China| Political education for political change" (1979). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1449. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1449 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUB SISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE: 19 7 9 "THOUGHT REFORM" IN CHINA: POLITICAL EDUCATION FOR POLITICAL CHANGE By Mary HeraJc B.A. University of Montana, 1972 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OP MONTANA 1979 Approved by: Graduat e **#cho o1 /- 7^ Date UMI Number: EP34293 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.