Comet Spring / Summer 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Diary Millom

Activities and Social Groups in the Millom Area ‘Part of the Cumbria Health and Social Wellbeing System’ supported by Cumbria County Council This social diary provides information on opportunities in the local community and on a wide range of services. It is listed by activities. Arts and Crafts Clubs: Craft Group Thwaites Village Hall, fortnightly, Wednesdays 2.00-4.00pm, Soup & Pudding lunch available prior to group 12.00-1.30pm (no sessions during summer months restarts in September). Visit the Website: www.thwaitesvillagehall.co.uk Haverigg Sewing Group St. Luke’s Institute , St. Luke’s Road, Haverigg. Weekly Wednesdays 7:30-9:30pm (Term time only). Contact Pam 07790116082 Kirksanton Art Group Kirksanton Village Hall, Kirksanton, weekly Tuesdays 1.00-3.00pm and Thursdays 6.30-8.30pm. Contact Dot Williams: 01229 776683 Kirksanton Quilters Group Kirksanton Village Hall, Kirksanton. Fortnightly - Wednesdays 2.00 to 4.00 pm. No meetings in July & August. New visitors welcome. Contact: Mrs M Griffiths 01229 773983 Needles & Hooks Knitting and Crocheting group, come along and join in the fun or just call in for a natter and friendly advice. Millom Library, St George’s Road, Millom, weekly Mondays 2.00-4.00pm, refreshments provided 50p donation. Contact the Library: 01229 772445 Millom & District Flower Club A monthly programme of demonstrators showcasing their diverse floral artistry, plus None members always welcome. Pensioners Hall, Mainsgate Road, Millom. Meets monthly last Thursday of the month 7.00pm. Contact Mrs Cunningham: 01229 774283 or Mrs Maureen Gleaves 01229 778189 Dance Classes: Old Time / Sequence Dancing Masonic Hall, Cambridge Street, Millom, weekly Wednesdays 7.30- 9.00pm. -

23 Feb 2021 Visit England's Regional Coastlines in 2021 and Explore the Extraordinary Outdoors…

Visit England’s regional coastlines in 2021 and explore the extraordinary outdoors… L-R: Chale & Blackgang, Isle of Wight; Harwich Mayflower Trail, Essex; the view from Locanda on the Weir, Somerset; Eskdale Railway, Lake District 9 February 2021 For travel inspiration across England’s coastline, visit E nglandscoast.com/en, the browse-and-book tool that guides you along the coast and everything it has to offer, from walking routes and heritage sites to places to stay and family attractions. Plan a trip, build an itinerary and book directly with hundreds of restaurants, cafés, pubs, hotels, B&Bs and campsites. “The coastline of England can rival that of any on the planet for sheer diversity, cultural heritage and captivating beauty,” says Samantha Richardson, Director, National Coastal Tourism Academy, which delivers the England’s Coast project. “No matter where you live, this is the year to explore locally. Take in dramatic views across the cliff-tops, explore charming harbour towns and family-friendly resorts like Blackpool, Scarborough, Brighton, Margate or Bournemouth. “Or experience culture on England’s Creative Coast in the South East; wherever you visit, you’re guaranteed to discover something new. Walk a stretch of the England Coast Path, enjoy world-class seafood or gaze at the Dark Skies in our National Parks near to the coast; England’s Coast re-energises and inspires, just when we need it most.” Whether one of England’s wonderful regional coastlines is on your doorstep or you’re planning a trip later in 2021, here are some unmissable experiences to enjoy in each region this year along with ways to plan your trip with E nglandscoast.com/en. -

North West Inshore and Offshore Marine Plan Areas

Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2015 Marshall Paul Macrae 1.0 Paul Macrae Updated draft final report following stakeholder consultation, August 2018 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Paul Macrae Final report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

The Baptist Missionary Society

THE BAPTIST MISSIONARY SOCIETY (Founded 1792) 134th ANNUAL REPORT For the year ending March 31st, 1926 LONDON: PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY AT THE CAREY PRESS 19, Furnival Street, E .C . 4. Telegraphic Address : “ Asiatic, Fleet, LondonT elephone: Holborn S882 (2 lines.) %*** CONTENTS. PAGE INTRODUCTORY NOTE .................................................................... 5 THE MISSIONARY ROLL CALL ... ... ... ... 6 MAPS ............................................................................................................ ... 9-12 PART II. THE SOCIETY : COMMITTEE AND OFFICERS, 1924-25, &c. 13 LIST OF MISSIONARIES .................................................................... 2G STATIONS AND STAFF ................................................................................. 46 STATISTICS AND TABLES .................................................................... 53 PART III. CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE SOCIETY .......................................... 87 ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTIONS AND DONATIONS ...................87-91 GIFT AND SELF-DENIAL W E E K ....................................................... 92 WOMEN’S FU N D .................................................... 97 MEDICAL FUND .............................................................................................. 98 BIBLE TRANSLATION AND LITERATURE FUND ................ 100 LONDON BAPTIST MISSIONARY UNION ............................. 101 ENGLISH COUNTY SUMMARIES ....................................................... 109 WALES : COUNTY SUMMARIES ...................................................... -

Download Our Exhibition Catalogue

CONTENTS Published to accompany the exhibition at Foreword 04 Two Temple Place, London Dodo, by Gillian Clarke 06 31st january – 27th april 2014 Exhibition curated by Nicholas Thomas Discoveries: Art, Science & Exploration, by Nicholas Thomas 08 and Martin Caiger-Smith, with Lydia Hamlett Published in 2014 by Two Temple Place Kettle’s Yard: 2 Temple Place, Art and Life 18 London wc2r 3bd Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: Copyright © Two Temple Place Encountering Objects, Encountering People 24 A catalogue record for this publication Museum of Classical Archaeology: is available from the British Library Physical Copies, Metaphysical Discoveries 30 isbn 978-0-9570628-3-2 Museum of Zoology: Designed and produced by NA Creative Discovering Diversity 36 www.na-creative.co.uk The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences: Cover Image: Detail of System According to the Holy Scriptures, Muggletonian print, Discovering the Earth 52 plate 7. Drawn by Isaac Frost. Printed in oil colours by George Baxter Engraved by Clubb & Son. Whipple Museum of the History of Science, The Fitzwilliam Museum: University of Cambridge. A Remarkable Repository 58 Inside Front/Back Cover: Detail of Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), Komei bijin mitate The Polar Museum: Choshingura junimai tsuzuki (The Choshingura drama Exploration into Science 64 parodied by famous beauties: A set of twelve prints). The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. Whipple Museum of the History of Science: Thinking about Discoveries 70 Object List 78 Two Temple Place 84 Acknowledgements 86 Cambridge Museums Map 87 FOREWORD Over eight centuries, the University of Cambridge has been a which were vital to the formation of modern understandings powerhouse of learning, invention, exploration and discovery of nature and natural history. -

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

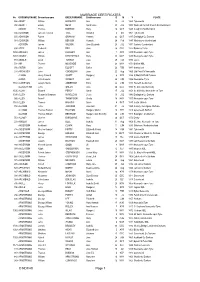

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Art and Life

Resource Notes – for teachers and group leaders Art and Life is an exhibition of paintings and pottery produced between 1920 and 1931 by artists Ben Nicholson, Winifred Nicholson, Christopher Wood, Alfred Wallis and William Staite Murray. All the artists knew each other personally, exhibited or worked together and shared similar values in terms of making art. Jim Ede, creator of Kettle's Yard, was a friend and a supporter of these artists, who played a central role in shaping his taste and approach to life. Their artwork makes up a key part of the Kettle’s Yard permanent collection. Art and Life shows British painting during a period of change, when representational painting was replaced by a more gestural, ‘felt’ abstraction. Painting was no longer about producing a technically accomplished representation of the real world, but about expressing 'lived' experience, through colour, form and movement. The process of making art came to be about the spiritual as well as the visual; about vitality, Winifred Nicholson, Autumn Flowers on a experience and intuition and re-connecting the Mantlepiece,1932. Oil on wood panel, 76 x person with life through art. 60cm. Private Collection © Trustees of Winifred Nicholson The Artists Winifred and Ben Nicholson grew up in an environment that gave them access to artists, artworks and intellectual society. Although working closely together, Winifred and Ben's paintings were quite different. Winifred's emphasis was strongly on colour and light whereas Ben focused more on line, muted colours and abstract, simple forms. Christopher Wood met the Nicholsons in 1926 and became a close friend, living with them for periods of time in Cumbria and St Ives, Cornwall. -

Welcome to the Laing Art Gallery and Articulation

WELCOME TO THE LAING ART GALLERY AND ARTICULATION The Laing Art Gallery sits in the heart of Newcastle City Centre and opened its doors in 1904 thanks to the local merchant Alexander Laing who gifted the gallery to the people of Newcastle. Unusually, when the Laing Art Gallery first opened, it didn’t have a collection! Laing was confident that local people would support the Gallery and donate art. In the early days the Gallery benefitted from a number of important gifts and bequests from prominent industrialists, public figures, art collectors, and artists. National galleries and museums continued to lend works, and, three years after opening its doors, the Laing began to acquire art. In 1907, the Gallery’s first give paintings were purchased. Over the last 100 years, the Laing’s curators have continued to build the collection, and it is now a Designated Collection, recognised as nationally important by Arts Council England. The Laing Art Gallery’s exceptional collection focuses on but is not limited to British oil paintings, watercolours, ceramics, and silver and glassware, as well as modern and contemporary pieces of art. We also run temporary exhibition programmes which change every three months. WELCOME TO THE LAING ART GALLERY! Here is your chosen artwork: 1933 (design) by Ben Nicholson Key Information: By Ben Nicholson Produced in 1933 Medium: Oil and pencil on panel Dimensions: (unknown) Location: Laing Art Gallery Currently on display in Gallery D PAINTING SUMMARY 1933 (design) is part of a series of works produced by Nicholson in the year of its title. The principle motif of these paintings is the female profile. -

International Rate Centers for Virtual Numbers

8x8 International Virtual Numbers Country City Country Code City Code Country City Country Code City Code Argentina Bahia Blanca 54 291 Australia Brisbane North East 61 736 Argentina Buenos Aires 54 11 Australia Brisbane North/North West 61 735 Argentina Cordoba 54 351 Australia Brisbane South East 61 730 Argentina Glew 54 2224 Australia Brisbane West/South West 61 737 Argentina Jose C Paz 54 2320 Australia Canberra 61 261 Argentina La Plata 54 221 Australia Clayton 61 385 Argentina Mar Del Plata 54 223 Australia Cleveland 61 730 Argentina Mendoza 54 261 Australia Craigieburn 61 383 Argentina Moreno 54 237 Australia Croydon 61 382 Argentina Neuquen 54 299 Australia Dandenong 61 387 Argentina Parana 54 343 Australia Dural 61 284 Argentina Pilar 54 2322 Australia Eltham 61 384 Argentina Rosario 54 341 Australia Engadine 61 285 Argentina San Juan 54 264 Australia Fremantle 61 862 Argentina San Luis 54 2652 Australia Herne Hill 61 861 Argentina Santa Fe 54 342 Australia Ipswich 61 730 Argentina Tucuman 54 381 Australia Kalamunda 61 861 Australia Adelaide City Center 61 871 Australia Kalkallo 61 381 Australia Adelaide East 61 871 Australia Liverpool 61 281 Australia Adelaide North East 61 871 Australia Mclaren Vale 61 872 Australia Adelaide North West 61 871 Australia Melbourne City And South 61 386 Australia Adelaide South 61 871 Australia Melbourne East 61 388 Australia Adelaide West 61 871 Australia Melbourne North East 61 384 Australia Armadale 61 861 Australia Melbourne South East 61 385 Australia Avalon Beach 61 284 Australia Melbourne -

Application Num 4/14/2131/0F1 Applicant Mr Hasan Denli, 46-47 Market Place, WHITEHAVEN, Cumbria CA28 7JB, Location 46-47 MARKE

Application Num 4/14/2131/0F1 Applicant Mr Hasan Denli, 46-47 Market Place, WHITEHAVEN, Cumbria CA28 7JB, Location 46-47 MARKET PLACE, WHITEHAVEN Proposal ALTERATIONS TO SHOP FRONT WINDOWS (RETROSPECTIVE); NEW DOOR TO REAR AND REPLACEMENT OF REAR WINDOWS Decision Refuse Decision Date 28 April 2015 Parish Whitehaven Application Num 4/14/2183/0O1 Applicant Lakeland Associates (Cleator) Ltd, Flosh Farm House, CLEATOR, Cumbria CA23 3DT, FAO Mr Richard Mullholland, Location LAND AT FLOSH FARM HOUSE, CLEATOR Proposal OUTLINE APPLICATION FOR HOUSING DEVELOPMENT Decision Approve Subject to S106 Decision Date 28 April 2015 Parish Cleator Moor Application Num 4/14/2232/0F1 Applicant Mr G Matthews, Sparrow Howe, Arlecdon Road, Arlecdon, FRIZINGTON, Cumbria CA26 3UW, Location SPARROW HOWE, ARLECDON ROAD, ARLECDON, FRIZINGTON Proposal WOODEN DECKING IN GARDEN TO REAR OF PROPERTY (RETROSPECTIVE) Decision Approve Decision Date 28 April 2015 Parish Arlecdon and Frizington Application Num 4/14/2337/0F1 Applicant Mr Hasan Denli, Charcoal Grill, 46-47 Market Place, WHITEHAVEN, Cumbria CA28 7JB, Location 46-47 MARKET PLACE, WHITEHAVEN Proposal CHANGE OF USE FROM A3 TO A5 (RETROSPECTIVE) Decision Approve Decision Date 28 April 2015 Parish Whitehaven Application Num 4/14/2520/0F1 Applicant E Granford, Netherholme, Saltcoates, HOLMROOK, Cumbria CA19 1YY, Location LEEWARD, DRIGG, HOLMROOK Proposal SINGLE STOREY EXTENSION AND LOFT CONVERSION WITH DORMERS (RESUBMISSION) Decision Approve (commence within 3 years) Decision Date 30 April 2015 Parish Drigg and Carleton -

Joys of the East TEFAF Online Running from November 1-4 with Preview Days on October 30 and 31

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp ISSUE 2463 | antiquestradegazette.com | 17 October 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 koopman rare art antiques trade KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Main picture: Jagat Singh II (1734-51) enjoying TEFAF moves a dance performance (detail) painted in Udaipur, c.1740. From Francesca Galloway. to summer Below: a 19th century Qajar gold and silver slot for 2021 inlaid steel vase. From Oliver Forge and Brendan Lynch. The TEFAF Maastricht fair has been delayed to May 31-June 6, 2021. It is usually held in March but because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic the scheduled dates have been moved, with the preview now to be held on May 29-30. The decision to delay was taken by the executive committee of The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF). Chairman Hidde van Seggelen said: “It is our hope that by pushing the dates of TEFAF Maastricht to later in the spring, we make physical attendance possible, safe, and comfortable for our exhibitors and guests.” Meanwhile, TEFAF has launched a digital marketplace for dealers with the first Joys of the East TEFAF Online running from November 1-4 with preview days on October 30 and 31. Two-part Asian Art in London begins with Indian and Islamic art auctions and dealer exhibitions Aston’s premises go This year’s ‘Islamic Week’, running from 29-November 7. -

The Temenos Academy

THE TEMENOS ACADEMY “T. S. Eliot and Kathleen Raine: Two Contemplative Poets” Author: Grevel Lindop Source: Temenos Academy Review 20 (2017) pp. 118-131 Published by The Temenos Academy Copyright © Grevel Lindop, 2017 The Temenos Academy is a Registered Charity in the United Kingdom www.temenosacademy.org T. S. Eliot and Kathleen Raine: Two Contemplative Poets* Grevel Lindop oets who are true mystics are very rare. Nonetheless there have P been, even in recent times, poets who approached contemplative experience despite living in a secular age and culture, where spiritual quests have seemed very much a minority interest. Neither T. S. Eliot nor Kathleen Raine was a mystic in the full sense. Eliot himself said, towards the end of his life in 1963, ‘I don’t think I am a mystic at all, though I have always been much interested in mysticism.’ And he added, ‘A great many people of sensibility have had some more or less mystical experiences. That doesn’t make them mystics. To be a mystic is a full-time job—so is poetry.’1 This may give us a key-signature, as it were, for approaching these two poets who were not mystics but who, in Eliot’s words, were ‘much interested in mysticism’ and had ‘some more or less mystical experiences’. To write about such experiences in poetry means, in some degree, attempting a communication of some aspect of them to the reader. And since mystical experience is notoriously incommunicable, this implies a particularly interesting challenge, or perhaps a paradox. T. S. Eliot was born in 1888 in St Louis, Missouri, and came to England, which became his permanent home, in 1915.