303 British 1 .303 British

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Bs150 3 Bs150 4 Bs150 5 Bs150 8 Bs150 10 Bs150 11

A CALL TO 1/32 English Civil War: Pikemen (20) ARMS 2 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 English Civil War: Royalist Musketeers (16) ARMS 3 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Zulu War: Zulus at Isandlwana (16) ARMS 4 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 English Civil War: Parliament Musketeers (16) ARMS 5 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 American Revolution: British Grenadiers (16) ARMS 8 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 American Revolution: American Maryland Infantry ARMS 10 (16) Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 American Civil War: Union Colored Infantry (16) ARMS 11 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: British Foot Guards (16) ARMS 12 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 English Civil War: Cannon (1) ARMS 13 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 English Civil War: Royalist Artillery (16) ARMS 14 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 American Civil War: Iron Brigade (16) ARMS 18 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: French Dragoons (8) ARMS 20 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: French Carabiniers (4 Mtd) ARMS 21 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: British Foot Artillery (16) ARMS 22 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: British 9-Pdr Cannon (1) ARMS 23 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Zulu War: Zulus at Ulundi (16) ARMS 24 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: Scots Greys (8) ARMS 25 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: Waterloo British Life Guards (8) ARMS 26 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: Waterloo Inniskilling Dragoons ARMS 27 (8) Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: Waterloo Belgium Infantry (16) ARMS 30 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Napoleonic Wars: Waterloo Dutch Infantry (16) ARMS 31 Bs150 A CALL TO 1/32 Revolutionary War: British Light Infantry (16) ARMS 32 Bs150 -

Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo Every boy that grew up in New Orleans (at least in my age group) that managed to get himself into the least bit of mischief knows that the local expression for a firecracker that doesn’t go off is a “shoo-shoo”. It means a dud, something that may have started off hot, but ended in a fizzle. It just didn’t live up to its expectations. It could also be used to describe other things that didn’t deliver the desired wallop, such as an over-promoted “hot date” or even a tropical storm that (fortunately) wasn’t as damaging as its forecast. Back in 1968, I thought for a moment that I was that “dud” date, but was informed by the young lady I was escorting that she had called me something entirely different. “Chou chou” (pronounced exactly like shoo-shoo) was a reduplicative French term of endearment, meaning “my little cabbage”. Being a “petite” healthy leafy vegetable was somehow a lot better than being a non-performing firecracker. At least I wasn’t the only one. In 2009 the Daily Mail reported on a “hugely embarrassing video” in which Carla Bruni called Nicolas Sarkozy my ‘chou chou’ and “caused a sensation across France”. Bruni and Sarkozy: no “shoo-shoo” here The glamourous former model turned pop singer planted a passionate kiss on the French President and then whispered “‘Bon courage, chou chou’, which means ‘Be brave, my little darling’.” The paper explained, “A ‘chou’ is a cabbage in French, though when used twice in a row becomes a term of affection between young lovers meaning ‘little darling’.” I even noticed in the recent French movie “Populaire” that the male lead called his rapid-typing secretary and love interest “chou”, which somehow became “pumpkin” in the subtitles. -

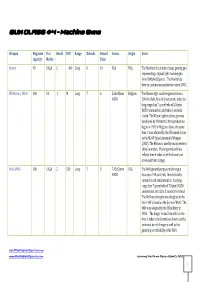

Machine Guns

GUN CLASS #4 – Machine Guns Weapon Magazine Fire Recoil ROF Range Reloads Reload Ammo Origin Notes capacity Modes Time Morita 99 FA,SA 2 400 Long 6 10 N/A N/A The Morita is the standard issue gaming gun representing a typical light machine gun from Battlefield Sports. The Morita has been in continuous manufacture since 2002. FN Minimi / M249 200 FA 2 M Long 7 6 5.56x45mm Belgium The Minimi light machine gun features a NATO 200 shot belt, fires fully automatic only, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 5.56mm NATO ammunition, and takes 6 seconds reload. The Minimi light machine gun was developed by FN Herstal. Mass production began in 1982 in Belgium. About the same time it was adopted by the US Armed forces as the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW). The Minimi is used by many western allied countries. The longer reload time reflects time it takes to let the barrel cool down and then change. M60 GPMG 100 FA,SA 2 550 Long 7 8 7.62x51mm USA The M60 general purpose machine gun NATO features a 100 shot belt, fires both fully automatic and semiautomatic, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 7.62mm NATO ammunition and takes 8 seconds to reload. The M60 machine gun was designed in the late 1940's based on the German MG42. The M60 was adopted by the US military in 1950. .The longer reload time reflects the time it takes to let barrel cool down and the awkward barrel change as well as the general poor reliability of the M60. -

Protective Force Firearms Qualification Courses

PROTECTIVE FORCE FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Office of Health, Safety and Security AVAILABLE ONLINE AT: INITIATED BY: http://www.hss.energy.gov Office of Health, Safety and Security Protective Force Firearms Qualification Courses July 2011 i TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION A – APPROVED FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES .......................... I-1 CHAPTER I . INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... I-1 1. Scope .................................................................................................................. I-1 2. Content ............................................................................................................... I-1 CHAPTER II . DOE FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSE DEVELOPMENT PROCESS ................................................................................ II-1 1. Purpose ..............................................................................................................II-1 2. Scope .................................................................................................................II-1 3. Process ..............................................................................................................II-1 4. Roles .................................................................................................................II-2 CHAPTER III . GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR FIREARMS QUALIFICATION COURSES.............................................................................III-1 CHAPTER IV -

20 March 2012, Compiled By: Phil Cregeen Pattern: Minimi C 9 LMG

NZART ID: 18 Arm Type: Machine Gun, Date of Draft: (V1) 20 March 2012, Compiled by: Phil Cregeen Pattern: Minimi C 9 LMG Introduced in to NZ Service: 1988, Withdrawn: In Service Maker: Thales, Lithgow Australia, Calibre: 5.56 mm, Cartridge : 5.56x45mm NATO , Magazine: belt or 30 round magazine, Rate of fire: 700 to 1150 rounds per min Barrel length: 465 mm, OA Length: 1038 mm, Height: 270 mm, Width: 110 mm, Weight: 6.48 Kg, Type of Action: Gas-operated, rotating bolt, Sights: rear aperture 300 – 1000 m Minimi C9 Light Machine Gun The 5.56 mm C9 Minimi Light Machine Gun is a fully automatic, air-cooled, gas operated weapon. It fires ammunition from disintegrating link belts or can be fed by magazines. It incorporates an open breech firing system and interchangeable barrels. This gun is the most common within the NZ Army and has been used as the army's Light Support Weapon (LSW) since 1988. The C9 can be converted for parachuting by fitting a carbine (shorter) barrel and collapsible stock, which reduces the overall length of the Standard C9 by 318 mm. The Minimi (short for French: Mini Mitrailleuse; "mini machine gun") is a Belgian 5.56mm light machine gun developed by Fabrique Nationale (FN) in Herstalby Ernest Vervier. First introduced in 1974, it has entered service with the armed forces of over thirty countries. The weapon is currently manufactured at the FN facility in Herstal and their US subsidiary FN Manufacturing LLC, as well as being licence-built in Australia, Italy, Japan, Sweden and Greece. -

Mg 34 and Mg 42 Machine Guns

MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS MC NAB © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS McNAB Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DEVELOPMENT 8 The ‘universal’ machine gun USE 27 Flexible firepower IMPACT 62 ‘Hitler’s buzzsaw’ CONCLUSION 74 GLOSSARY 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Although in war all enemy weapons are potential sources of fear, some seem to have a deeper grip on the imagination than others. The AK-47, for example, is actually no more lethal than most other small arms in its class, but popular notoriety and Hollywood representations tend to credit it with superior power and lethality. Similarly, the bayonet actually killed relatively few men in World War I, but the sheer thought of an enraged foe bearing down on you with more than 30cm of sharpened steel was the stuff of nightmares to both sides. In some cases, however, fear has been perfectly justified. During both world wars, for example, artillery caused between 59 and 80 per cent of all casualties (depending on your source), and hence took a justifiable top slot in surveys of most feared tools of violence. The subjects of this book – the MG 34 and MG 42, plus derivatives – are interesting case studies within the scale of soldiers’ fears. Regarding the latter weapon, a US wartime information movie once declared that the gun’s ‘bark was worse than its bite’, no doubt a well-intentioned comment intended to reduce mounting concern among US troops about the firepower of this astonishing gun. -

Part II (A) Non-Russian Motorcycles with Machine Guns and MG Mounts

PartPart IIII (A)(A) NonNon--RussianRussian MotorcyclesMotorcycles withwith MachineMachine GunsGuns andand MGMG MountsMounts ErnieErnie FrankeFranke Rev.Rev. 1:1: 05/201105/2011 [email protected]@tampabay.rr.com NonNon--RussianRussian MotorcyclesMotorcycles byby CountryCountry • Universal Role of Adding Machine Guns to Motorcycles • American –Indian –Harley-Davidson –Kawasaki • British –Clyno –Royal Enfield –Norton • Danish –Harley-Davidson –Nimbus • Dutch –Swiss Motosacoche –FN Products (Belgium) –Norton –Harley-Davidson • German –BMW –Zundapp • Italy –Moto Guzzi • Chinese –Chang Jiang • Russian –Ural Man has been trying to add a machine gun to a sidecar for many years in many countries. American: Browning 1895 on a Harley-Davidson Sidecar (browningmgs.com) World War-One (WW-I) machine gun mounted on Indian motorcycle with sidecar. American:American: MotorcycleMotorcycle MachineMachine GunGun (1917)(1917) (www.usmilitariaforum.com) World War-One (WW-I) machine gun mounted on a Indian motorcycle with sidecar. American:American: BenetBenet--MercieMercie mountedmounted onon IndianIndian (forums.gunboards.com) It is hard to see how any accuracy could be achieved while on the move, so the motorcycle had to be stopped before firing. American:American: MilitaryMilitary IndianIndian SidecarsSidecars (browningmgs.com) One Indian has the machine gun, the other has the ammo. American: First Armored Motor Battery of NY and Fort Gordon, GA (www.motorcycle-memories.com and wikimedia.org) (1917) The gun carriage was attached as a trailer to a twin-cylinder motorcycle. American:American: BSABSA (info.detnews.com) World War-Two (WW-II) 50 cal machine gun mounted on a BSA motorcycle with sidecar. American:American: HarleyHarley--DavidsonDavidson WLAWLA ModelModel Ninja Warriors! American:American: "Motorcycle"Motorcycle ReconnaissanceReconnaissance TroopsTroops““ byby RolandRoland DaviesDavies Determined-looking motorcycle reconnaissance troops head towards the viewer, with the first rider's Thompson sub machine-gun in action. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

E - Gazette Mk II

E - Gazette Mk II New Zealand Antique & Historical Arms Association Inc. # 19 July 2012 EDITORIAL May proved to be a great month for my collecting interests, I scored a Ross M 10 from my mate Pat, a Brown Bess from Ted Rogers auction, a great book on British Service Revolvers from Carvell’s auction, spent a fantastic day at the Lithgow SAF Museum, and another at the Australian War Memorial Museum in Canberra and finally the National Maritime Museum in Sydney. Now I just have to pay off the Visa card! In June the Small Arms Factory at Lithgow celebrated its Centenary, it officially opened on 8 June 1912 and went on to manufacture over 640,000 SMLE rifles as well as Vickers and Bren guns, followed by SLRs and Steyrs, many of which have served our own Armed Forces. To the workers past and present at the factory and the volunteers at the museum we send our best wishes. Once again my thanks to our readers who have sent comment or material for publication. If you have comments to make or news or articles to contribute, send them to [email protected] All views (and errors) expressed here are those of the Editor and not necessarily those of the NZAHAA Inc. Phil Cregeen, Editor [email protected] STOLEN GUNS On 20 th June I circulated two lists of stolen firearms and items of militaria to you. In one case the owner was asleep in bed when the burglary took place without him hearing anything to arouse his suspicion, in the other case the theft took place when the guns were in transit. -

Canadian Military Journal

CANADIAN MILITARY JOURNAL Vol. 18, No. 3, Summer 2018 Vol. 18, No. 3, Summer 2018 CONTENTS 3 EDITOR’S CORNER THE WORLD IN WHICH WE LIVE 5 ‘Wolves of the Russian Spring’: An Examination of the Night Wolves as a Proxy for the Russian Government by Matthew A. Lauder MILITARY PROFESSIONAL THOUGHT Cover 17 Missed Steps on a Road Well-Travelled: Strong, Secure, Engaged The Black Devils Clearing and Deterrence No-Man’s Land (Anzio, 1944) by Andrew J. Duncan © Painting by Silvia Pecota, 26 Left Out of Battle: Professional Discourse in the Canadian Armed Forces www.silviapecota.com by Howard G. Coombs 37 In Defence of Victory: A Reply to Brigadier-General Carignan’s “Victory as a Strategic Objective” by John Keess MILITARY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 47 The Implications of Additive Manufacturing on Canadian Armed Forces Operational Functions by Christopher Bayley and Michael Kopac 55 Prepare for the Flood before the Rain: The Rise and Implications of Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems (LAWS) by Caleb Walker ‘Wolves of the Russian Spring’: An Examination VIEWS AND OPINIONS of the Night Wolves as 62 Historical Insights to Strategic Challenges a Proxy for the Russian by Dave Johnston Government 67 Child Soldiers by Christopher J. Young COMMENTARY 70 The Fighter Replacement Conundrum by Martin Shadwick 78 BOOK REVIEWS Missed Steps on a Road Well-Travelled: Strong, Secure, Engaged and Deterrence Canadian Military Journal/Revue militaire canadienne is the official professional journal of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence. It is published quarterly under authority of the Minister of National Defence. -

World Warworld

You can visit the galleries in this trail BATTLE in any order SOCIETY nam.ac.uk UPPER LEVEL BATTLE SOCIETY ARMY LOWER LEVEL ARMY FIRST FLOOR Temporary Exhibition Space Toilets UPPER LEVEL Café Toilets SOLDIER LOWER LEVEL SOLDIER Play Base Shop Welcome Desk GROUND FLOOR Main Entrance FIRST Toilets Group Entrance WORLD WAR UPPER LEVEL Atrium Foyle Centre Group Entrance Discover life in INSIGHT LOWER LEVEL the Great War INSIGHT Discover More and design a new Templer Study KEY Centre & Archive war memorial... STAGE 3-5 Toilets LOWER GROUND FLOOR SCHOOLS TRAIL FIRST WORLD WAR IN SOLDIER GALLERY Becoming soldiers Did you know that millions of people served during the To understand the contribution people made during the First World First World War? The conflict dramatically changed War, you will need to investigate their reactions to war and the warfare and British society. range of experiences they had. You are an architect in charge of designing a new memorial to commemorate those who served during the First World War. You will need to do background research into who was involved, what their experiences How did soldiers prepare for war? were like, and the technology they used by looking for Follow the gallery round and look left for the Short Magazine evidence in the National Army Museum. Your future Lee-Enfield rifle. How many weeks of basic training did soldiers receive with this weapon? design should accurately reflect the men and women who served Britain. ....................................................................................................................... This trail takes you to four different galleries in the Museum and What did soldiers eat? you can visit them in any order. -

Before the Storm – Scenario Pack 1

Introduction Hello to all you gamers out there! Warlord Games’ 75th Anniversary D-Day Campaign is going to be a truly magnificent undertaking. We’re hoping to capture the essence of Eisenhower’s great crusade to recapture Occupied Europe with lots of fantastic articles and scenarios to help get you involved and excited about playing games! These packs of scenarios have been designed to give you a flavour of the wider conflict - ranging from small groups of commandos sneaking up deserted beaches, to huge set- piece battles between the armies of the Axis and the Allies. We’re going to cover the whole Bolt Action games family - Bolt Action, Blood Red Skies and Cruel Seas, along with rules to help link your games together and weave a narrative worthy of the silver screen. (Ed: Keep an eye out for a few surprise appearances from some of our other titles as well.) Before the Storm covers some of the key events leading up to D-Day, including a Christmas Eve raid on the Dutch coast, French partisans blowing up railway lines to slow the German advance and a daring reconnaissance mission performed by RAF Mosquitos. Make sure you follow us on all our social media channels and let us know what you think of the campaign and the material we’re putting out to support us. It’s so important that we get feedback from you so we can continue to produce some of the best wargames on the market. John Stallard, May 2019 2 Contents CHRISTMAS HARDTACK 4 VIOLINS OF AUTUMN 6 FIREFIGHT! 8 POSTAGE ABLE 10 Snap-Happy 12 Plywood Sleigh 14 3 CHRISTMAS HARDTACK Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house, not a creature was stirring.