Rethinking Abiogenesis: Part II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

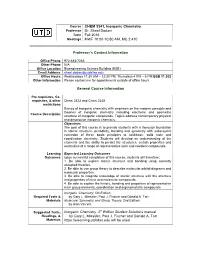

Course CHEM 3341, Inorganic Chemistry Professor Dr. Sheel Dodani Term Fall 2016 Meetings MWF 10:00-10:50 AM, MC 2.410

Course CHEM 3341, Inorganic Chemistry Professor Dr. Sheel Dodani Term Fall 2016 Meetings MWF 10:00-10:50 AM, MC 2.410 Professor’s Contact Information Office Phone 972-883-7283 Other Phone N/A Office Location Bioengineering Science Building (BSB) Email Address [email protected] Office Hours Wednesdays 11:30 AM – 12:30 PM, Thursdays 4 PM – 5 PM BSB 11.302 Other Information Please contact me for appointments outside of office hours General Course Information Pre-requisites, Co- requisites, & other Chem 2323 and Chem 2325 restrictions Survey of inorganic chemistry with emphasis on the modern concepts and theories of inorganic chemistry including electronic and geometric Course Description structure of inorganic compounds. Topics address contemporary physical and descriptive inorganic chemistry. Objectives The goal of this course is to provide students with a thorough foundation in atomic structure, periodicity, bonding and symmetry with subsequent extension of these basic principles to acid/base, solid state and coordination chemistry. Students will develop an understanding of the elements and the ability to predict the structures, certain properties and reactivities of a range of representative ionic and covalent compounds. Learning Expected Learning Outcomes Outcomes Upon successful completion of this course, students will therefore: 1. Be able to explain atomic structure and bonding using currently accepted theories. 2. Be able to use group theory to describe molecular orbital diagrams and molecular properties. 3. Be able to integrate knowledge of atomic structure with the structure and properties of ionic and molecular compounds. 4. Be able to explain the history, bonding and properties of representative main group elements, coordination and organometallic compounds Inorganic Chemistry, 5th Edition Required Texts & by Gary L. -

General Inorganic Chemistry

General Inorganic Chemistry Pre DP Chemistry Period 1 • Teacher: Annika Nyberg • [email protected] • Urgent messages via Wilma! Klicka här för att ändra format på underrubrik i bakgrunden • Course book: • CliffsNotes: Chemistry Quick Review http://www.chem1.com/acad/webtext/virtualtextbook.html Content • Introduction • The Structure of Matter (Chapter 1) • The Atom (Chapter 2 and 3) • Chemical bonding (Chapter 5) • The Mole (Chapter 2) • Solutions (Chapter 9) • Acids and bases (Chapter 10) • Quiz • Revision • EXAM 9.00-11.45 Assessment Exam: 80 % Quiz: 20% + practical work, activity and absences 1. Chemistry: a Science for the twenty-first century ● Chemistry has ancient roots, but is now a modern and active, evolving science. ● Chemistry is often called the central science, because a basic knowledge of chemistry is essential for students in biology, physics, geology and many other subjects. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tTlnrhiadnI ● Chemical research and development has provided us with new substances with specific properties. These substances have improved the quality of our lives. Health and medicine vaccines sanitation systems antibiotics anesthesia and all other drugs Energy new alternative energy sources (e.g. solar energy to electric energy, nuclear fission) electric cars with long lasting batteries Environment greenhouse gases acid rain and smog Materials and Technology ● polymers (rubber and nylon), ceramics (cookware), liquid crystals (electronic displays), adhesives (Post-It notes), coatings (latex-paint), silicon chips (computers) Food and Agriculture substances for biotechnology ● The purpose of this course is to make you understand how chemists see the world. ● In other words, if you see one thing (in the macroscopic world) you think another (visualize the particles and events in the microscopic world). -

Revised Glossary for AQA GCSE Biology Student Book

Biology Glossary amino acids small molecules from which proteins are A built abiotic factor physical or non-living conditions amylase a digestive enzyme (carbohydrase) that that affect the distribution of a population in an breaks down starch ecosystem, such as light, temperature, soil pH anaerobic respiration respiration without using absorption the process by which soluble products oxygen of digestion move into the blood from the small intestine antibacterial chemicals chemicals produced by plants as a defence mechanism; the amount abstinence method of contraception whereby the produced will increase if the plant is under attack couple refrains from intercourse, particularly when an egg might be in the oviduct antibiotic e.g. penicillin; medicines that work inside the body to kill bacterial pathogens accommodation ability of the eyes to change focus antibody protein normally present in the body acid rain rain water which is made more acidic by or produced in response to an antigen, which it pollutant gases neutralises, thus producing an immune response active site the place on an enzyme where the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) an increasing substrate molecule binds problem in the twenty-first century whereby active transport in active transport, cells use energy bacteria have evolved to develop resistance against to transport substances through cell membranes antibiotics due to their overuse against a concentration gradient antiretroviral drugs drugs used to treat HIV adaptation features that organisms have to help infections; they -

Chemistry ‐ Student Learning Outcomes CHEM 100 Introduction to Chemistry 1.Analyze Chemical Reactions and Chemical Problems Through Stoichiometry

Chemistry ‐ Student Learning Outcomes CHEM 100 Introduction To Chemistry 1.analyze chemical reactions and chemical problems through stoichiometry. (ILO2) 2. predict properties of matter using atomic theory. (ILO2) 3. use the periodic table properly to determine trends in elements (atomic size, number of valence electrons, metallic character, electronegativity, etc.). (ILO2, ILO4) 4. perform chemical experiments in a safe, accurate, and scientific manner, using proper glasswares, graphs, and spreadsheets. (ILO2, ILO4) CHEM 160 Introduction to General, 1. calculate drug dosage using English and Metric unit interconversions and dimensional Organic & Biological analysis. (ILO4) Chemistry 2. identify different classes of organic compounds. (ILO2) 3. identify different functional groups in organic compounds. (ILO2) 4. write a research paper on biochemical disorders. (ILO4) 5. discuss the geographical/ethnic distribution of biochemical disorders. (ILO5) CHEM 200 General Inorganic Chemistry I 1. perform dimensional analysis calculations as they relate to problems involving percent composition and density. (ISLO2) 2. write chemical formulas, and name inorganic compounds. (ISLO2) 3. relate chemical equations and stoichiometry as they apply to the mole concept. (ISLO2) 4. identify the basic types of chemical reactions including precipitation, neutralization, and oxidation‐reduction. (ISLO4) 5. knowledge of atomic structure and quantum mechanics and apply these concepts to the study of periodic properties of the elements. (ISLO4) CHEM 202 General Inorganic Chemistry 1. examine and develop concepts of covalent bonding, orbital hybridization and II molecular orbital theory. (ISLO4) 2. identify and perform organic addition and elimination reactions. (ISLO2) 3. compare and analyze Thermodynamics properties and differentiate between spontaneity and maximum useful work heat and Free energy. (ISLO2) 4. -

CHEM 110 Week 1 Inorganic Chemistry I Atoms, Elements, and Compounds

CHEM 110 Week 1 Inorganic Chemistry I Atoms, Elements, and Compounds Week 1 Reading Assignment Your week 1 reading assignment has been selected from chapters 3 and 5 in your textbook. As part of your reading assignment, you are expected to work the sample problems and the selected “questions and problems” at the end of your book sections. The answers to the odd numbered “questions and problems” can be found at the end of your book chapters. You should use this key to check yourself. If you are having problems arriving at the correct answer as listed in the back of your book chapter, please email me. Read section 3.1 and answer the odd numbered “questions and problems” on page 85. Read section 3.2 and answer the odd numbered “questions and problems” on page 91. Read section 3.3 and answer “questions and problems” 3.15 and 3.17 on page 94. You do not have to know the experimental details used to determine the structure of an atom. Read section 3.4 and answer the odd numbered “questions and problems” on page 97. Read about isotopes and atomic mass in section 3.5 and answer “questions and problems” 3.29 and 3.31 on page 100. Skip the part on calculating atomic mass using isotopes. Read section 3.6. Read section 3.7. Read about “Group Number and Valence Electrons” and “Electron-Dot Symbols” in section 3.8. Answer “questions and problems” 3.57 and 3.59 on page 118. Read section 5.1 and answer the odd numbered “questions and problems” on page 163 and 164. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

25Th Anniversary of Molecules—Recent Advances in Inorganic Chemistry

molecules Editorial 25th Anniversary of Molecules—Recent Advances in Inorganic Chemistry Burgert Blom 1,* , Erika Ferrari 2 , Vassilis Tangoulis 3 ,Cédric R. Mayer 4, Axel Klein 5 and Constantinos C. Stoumpos 6 1 Maastricht Science Programme, Assistant Professor of Inorganic Chemistry and Catalysis, Maastricht University, Kapoenstraat 2, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands 2 Department of Chemical and Geological Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Via Campi 103, 41125 Modena, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Chemistry, University of Patras, 26504 Patras, Greece; [email protected] 4 Laboratoire LuMin, FRE CNRS 2036, CNRS, Université Paris-Sud, ENS Paris-Saclay, Centrale Supelec, Université Paris-Saclay, F-91405 Orsay CEDEX, France; [email protected] 5 Department für Chemie, Institut für Anorganische Chemie, Universität zu Köln, Greinstraße 6, 50939 Köln, Germany; [email protected] 6 Department of Chemistry, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Celebrating the “25th Anniversary of Molecules” with a Special Issue dedicated to “Recent Advances in Inorganic Chemistry” strengthens the renewed role that inorganic chemistry, one of the oldest chemistry divisions, has lately earned thanks to cutting-edge perspectives and interdisciplinary applications, eventually receiving the veneration and respect which its age might require [1,2]. The last 25 years have seen staggering advances in both solid-state, molecular, catalytic Citation: Blom, B.; Ferrari, E.; Tangoulis, V.; Mayer, C.R.; Klein, A.; and bio-inorganic chemistry. Some notable highlights in molecular inorganic chemistry Stoumpos, C.C. 25th Anniversary of over the last 2.5 decades certainly must include the propensity of heavy p-block elements Molecules—Recent Advances in (those in period 3 or higher) to undergo multiple bonding with other heavy p-block Inorganic Chemistry. -

Introduction to Marine Biology

Short Communication Volume 10:S1, 2021 Molecular Biology ISSN: 2168-9547 Open Access Introduction to Marine Biology Subhashree Sahoo* Trident College, Bhubaneswar, Odisha 751024, India Abstract Introduction to marine biology is a 3-praise lesson credited finished the Florida Solutions Communal University. It includes a smallest of 45 interaction times that comprise together addresses and applied actions. This lesson canister usually is alienated in four units. Marine biology is a newer science than earthly ecology as initial experts were incomplete in their education of water creatures through absence of skill toward detect and example them. The Greek theorist Aristotle was unique of the 1st to project an organization system for alive organisms, which he named “the ladder of life” and in which he designated 500 classes, numerous of which were maritime. He also deliberates fish gills and cuttlefish. The Roman biologist Pliny the Leader available a 37-volume effort named Natural History, which limited numerous maritime classes. Slight effort on usual past remained showed throughout the central days, and it wasn’t pending the nighttime 18th period and initial 19th period that attention in the maritime setting was rehabilitated, powered through examinations now complete conceivable through healthier vessels and better steering methods. Keywords: Molecular, Biology, Marine. Introduction has an optimum variety of apiece ecological issue that touches it. Outdoor of this best, regions of pressure exist, anywhere the creature may nosedive toward replicate. Most maritime creatures are ectotherms, powerless toward Fish source the highest measurement of the universe protein expended switch their interior text infection, so fast or loosing warmth after their outside through persons. -

Nutritional Disorders and Food Development: Problems and Potential Solutions Ion C

al Dis ion ord rit e t rs u N & f T o h l e a Baianu, J Nutr Disorders Ther 2012, 2:3 r n a r p u y DOI: 10.4172/2161-0509.1000e103 o Journal of Nutritional Disorders & Therapy J ISSN: 2161-0509 Editorial Open Access Nutritional Disorders and Food Development: Problems and Potential Solutions Ion C. Baianu* AFC-NMR & NIR Microspectroscopy Facility, College of ACES, FSHN & NPRE Departments, University of Illinois at Urbana, Urbana, IL 61801, USA Nutrition-related disorders are increasingly wide-spread in the preparations that can be however obtained as inexpensive ingredients United States of America and the European Union. There are major in large quantities in the US markets. However, there are yet no foods concerns about the recent rise in obesity-related diseases, such as type based on the konjac flour ingredient in the US supermarkets that II diabetes, as well as heart diseases, especially coronary artery disease could help a large and increasing population of diabetic patients and (CAD) and atherosclerosis. The latter is the number one cause of deaths overweight Americans. The remaining question is: how long will take in the Western World. to bring such konjac-based, healthy foods into the US food supply? Potential solutions to such major nutrition-related, major problems This is only one example of how novel approaches that employ of modern society require a rational approach to finding adequate food physical chemistry results and complex systems analysis may solutions that are both effective and practical to achieve a long term rapidly benefit the US food consumer in the near future. -

Lerner's Concept of Developmental Homeostasis and the Problem of Heterozygosity Level in Natural Populations

Heredity 55 (1985) 341—353 The Genetical Society of Great Britain Received 20 March 1985 Lerner's concept of developmental homeostasis and the problem of heterozygosity level in natural populations G. Livshits and E. Kobyliansky Department of Anatomy and Anthropology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel. In recent years adherents of the neutral mutation hypothesis have conducted a variety of statistical tests concerning the applicability of their theory to data of biochemical genetic polymorphism in natural populations. From the other side, the involvement of natural selection as a main evolutionary force responsible for the observed levels of polymorphism and heterozygosity have also been proposed in numerous field studies and theoretical considerations. However, none of these hypotheses completely and satisfactorily explains the collected data. We believe that one of the main causes of the discrepancy in theories is that the variability at each locus is considered independently in both of the above- mentioned approaches. Yet, it was suggested long ago, and now there is an increasing amount of evidence indicating cooperation between different loci which can influence the variability at each of them. Thus we think that the use of models considering the genome as a suit of independent genes is a priori expected to decrease the efficacy of the approximation. In the present review we attempt to draw attention to findings of interdependence of the variability of different characters and its possible limiting action on the growth of genetic diversity in natural populations. We do not try to give a universal explanation for the processes acting in populations and determining levels of heterozygosity. -

Faculty of Home Economics

Faculty of Home Economics 【Department of Food Science and Nutrition Food Science Program】 *Subject* *CREDITS* First Year Seminar 2 Japanese Skills I(Composition/Essay Writing) 1 Japanese Skills II(Reading Comprehension/Text Analysis) 1 Japanese Skills III(Presentation/Debate) 1 English I 2 English II 2 Business English I 2 Business English II 2 Oral Communication 2 TOEIC/TOEFL Seminar 2 Basic French (Introduction) 2 Basic French (Speaking and Writing) 2 Practical French 2 Basic Chinese (Introduction) 2 Basic Chinese (Speaking and Writing) 2 Practical Chinese 2 Basic German (Introduction) 2 Basic German (Speaking and Writing) 2 Practical German 2 Basic Spanish (Introduction) 2 Practical Spanish 2 Basic Italian (Introduction) 2 Practical Italian 2 Basic Russian (Introduction) 2 Practical Russian 2 Basic Korean (Introduction) 2 Practical Korean 2 Basic Arabic I 1 Basic Arabic II 1 Basic Information Processing 2 Use of Application Software 2 Database Skills 2 Computer Networking Skills 2 Basic Statistics 2 Practical Statistical Analysis 2 Health&Physical Education Practice A 1 Health&Physical Education Practice B 1 Cross-disciplinary Course 2 Ideas in Comparative Cultural Studies 2 The Media and Culture 2 The World of Literature 2 The World of the Arts 2 Design Today 2 The Culture of Housing,Food and Clothing 2 The Environment and Amenities 2 Health Science 2 Nursing Care and Daily Life 2 Issues in Politics and Society 2 Issues in Economics and Industry 2 Issues in International Relations 2 Issues in Environmental Studiesand Science 2 The -

Spontaneous Generation & Origin of Life Concepts from Antiquity to The

SIMB News News magazine of the Society for Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology April/May/June 2019 V.69 N.2 • www.simbhq.org Spontaneous Generation & Origin of Life Concepts from Antiquity to the Present :ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌŝĂůDŝĐƌŽďŝŽůŽŐLJΘŝŽƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ Impact Factor 3.103 The Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology is an international journal which publishes papers in metabolic engineering & synthetic biology; biocatalysis; fermentation & cell culture; natural products discovery & biosynthesis; bioenergy/biofuels/biochemicals; environmental microbiology; biotechnology methods; applied genomics & systems biotechnology; and food biotechnology & probiotics Editor-in-Chief Ramon Gonzalez, University of South Florida, Tampa FL, USA Editors Special Issue ^LJŶƚŚĞƚŝĐŝŽůŽŐLJ; July 2018 S. Bagley, Michigan Tech, Houghton, MI, USA R. H. Baltz, CognoGen Biotech. Consult., Sarasota, FL, USA Impact Factor 3.500 T. W. Jeffries, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA 3.000 T. D. Leathers, USDA ARS, Peoria, IL, USA 2.500 M. J. López López, University of Almeria, Almeria, Spain C. D. Maranas, Pennsylvania State Univ., Univ. Park, PA, USA 2.000 2.505 2.439 2.745 2.810 3.103 S. Park, UNIST, Ulsan, Korea 1.500 J. L. Revuelta, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain 1.000 B. Shen, Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL, USA 500 D. K. Solaiman, USDA ARS, Wyndmoor, PA, USA Y. Tang, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA E. J. Vandamme, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium H. Zhao, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, USA 10 Most Cited Articles Published in 2016 (Data from Web of Science: October 15, 2018) Senior Author(s) Title Citations L. Katz, R. Baltz Natural product discovery: past, present, and future 103 Genetic manipulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis for improved production in Streptomyces and R.