The Prism of COGSA, 30 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Washington State Census Board and Its Demographic Legacy

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN POPULATION STUDIES David A. Swanson The Washington State Census Board and Its Demographic Legacy 123 SpringerBriefs in Population Studies More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10047 David A. Swanson The Washington State Census Board and Its Demographic Legacy 123 David A. Swanson Department of Sociology University of California Riverside USA ISSN 2211-3215 ISSN 2211-3223 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Population Studies ISBN 978-3-319-25947-5 ISBN 978-3-319-25948-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-25948-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015954599 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

The Great Depression in Monmouth County: an Exhibition at the Monmouth County Library Headquarters 125 Symmes Drive Manalapan, New Jersey October 2009

The Great Depression in Monmouth County: An Exhibition at the Monmouth County Library Headquarters 125 Symmes Drive Manalapan, New Jersey October 2009 Organized by The Monmouth County Archives Gary D. Saretzky, Curator Eugene Osovitz, Preparer “Illdestined Morro Castle off Beach at Asbury Park,” Sept. 9, 1934 Monmouth County Archives, Acc. #2007-12 Gift of Fred Sisser Produced by the Monmouth County Archives 125 Symmes Drive Manalapan, NJ 07726 http://visitmonmouth.com/archives Acknowledgments The special month-long exhibit in the lobby of the Monmouth County Library, “The Great Depression in Monmouth County,” was curated by Gary D. Saretzky with exhibit preparation by Eugene Osovitz. Joya Anderson of the Archives staff produced digital prints of many of the exhibit items. The curved wall portion of the exhibit was mounted by the Monmouth County Art Department under the direction of Roberta Ohliger. Editorial assistance for the exhibition catalog was provided by Patrick Caiazzo. This exhibit was drawn from the collections of the Monmouth County Archives, several other repositories, and a private collector. The cooperation of the following individuals and organizations who lent or provided materials for the exhibition is gratefully acknowledged: Bette Epstein and Joanne Nestor, New Jersey State Archives; Ron Becker, Michael Joseph, and Caryn Radick, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University; George Hawley, Newark Public Library; Laura Poll, Monmouth County Historical Association; Art Anderson; and Wendy Nardi. Images of Jersey Homesteads in this exhibit were obtained from the American Memory website of the Library of Congress, a national treasure, and articles from the Red Bank Register were printed from the very useful online version on the website of the Middletown Township Public Library. -

Out of Uniform Compliance Bushfire Non-Traditional Outlook Volunteering Rethinking Risk Advanced Automatic Fire Detection Systems

Spring 2014 confronting product out of uniform compLiance bushfire Non-traditional outLook volunteering rethinking risk Advanced Automatic Fire Detection Systems Leading Australian fire professionals choose PERTRONIC fire systems A network of Pertronic F120A fire alarm panels protects the occupants of Brisbane’s 81-storey Infinity Tower PERTRONIC INDUSTRIES PTY LTD Melbourne Sydney Brisbane Adelaide Perth PH 03 9562 7577 PH 02 9638 7655 PH 07 3255 2222 PH 08 8340 9533 PH 08 6555 3008 Fax 03 9562 8044 Fax 02 9638 7688 Fax 07 3054 1458 Fax 08 8340 9544 Fax 08 9248 3783 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2 | Fire AustrAliA spring 2014 www.pertronic.com.au 18 14 26 Spring 2014 Joint editors In thIs Issue Joseph Keller (FpA Australia) 14 Rethinking risk—empowering tel +61 3 8892 3131 communities adveRtIseR emAil [email protected] lIstIng 18 Product compliance—the 2 Pertronic nathan maddock (Bushfire and natural confronting reality 4 WBS Technology Hazards CrC) 22 Preventing fire and protecting 7 Archer Testing tel +61 3 9412 9605 9 CSR Bradford emAil [email protected] assets with oxygen-reduction systems 10 Lorient mandy Cant (AFAC) 1 3 Volvo tel +61 3 9419 2388 26 Higher than normal risk this fire 1 7 Australian Fire emAil [email protected] season Enterprises 2 1 Fire Australia 2015 28 Learning from adversity at key 25 FireSense Fire protection Association Australia industry conference (FpA Australia) ABn 30 005 366 576 -

Butler Hansen a Trailblazing Washington Politician John C

Julia Butler Hansen A trailblazing Washington politician John C. Hughes Julia Butler Hansen A trailblazing Washington politician John C. Hughes First Edition Second Printing Copyright © 2020 Legacy Washington Office of the Secretary of State All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-889320-45-8 Ebook ISBN 978-1-889320-44-1 Front cover photo: John C. Hughes Back cover photo: Hansen Family Collection Book Design by Amber Raney Cover Design by Amber Raney and Laura Mott Printed in the United States of America by Gorham Printing, Centralia, Washington Also by John C. Hughes: On the Harbor: From Black Friday to Nirvana, with Ryan Teague Beckwith Booth Who? A Biography of Booth Gardner Nancy Evans, First-Rate First Lady Lillian Walker, Washington State Civil Rights Pioneer The Inimitable Adele Ferguson Slade Gorton, a Half Century in Politics John Spellman: Politics Never Broke His Heart Pressing On: Two Family-Owned Newspapers in the 21st Century Washington Remembers World War II, with Trova Heffernan Korea 65, the Forgotten War Remembered, with Trova Heffernan and Lori Larson 1968: The Year that Rocked Washington, with Bob Young and Lori Larson Ahead of the Curve: Washington Women Lead the Way, 1910-2020, with Bob Young Legacy Washington is dedicated to preserving the history of Washington and its continuing story. www.sos.wa.gov/legacy For Bob Bailey, Alan Thompson and Peter Jackson Julia poses at the historic site sign outside the Wahkiakum County Courthouse in 1960. Alan Thompson photo Contents Preface: “Like money in the bank” 6 Introduction: “Julia Who?” 10 Chapter 1: “Just Plain Me” 17 Chapter 2: “Quite a bit of gumption” 25 Chapter 3: Grief compounded 31 Chapter 4: “Oh! Dear Diary” 35 Chapter 5: Paddling into politics 44 Chapter 6: Smart enough, too 49 Chapter 7: Hopelessly disgusted 58 Chapter 8: To the last ditch 65 Chapter 9: The fighter remains 73 Chapter 10: Lean times 78 Chapter 11: “Mrs. -

A Forest Kingdom Unlike Any Other

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 1979 A Forest Kingdom Unlike Any Other Kurt F. Ruppel Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons Recommended Citation Ruppel, Kurt F., "A Forest Kingdom Unlike Any Other" (1979). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 222. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FOREST KINGDOMUNLIKE ANY OTHER by Kurt F. Ruppel A senior thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOROF SCIENCE Wildlife Sci~nce (Honors) Approved by: UTAHSTATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1979 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people were instrumental in the formation and completion of this study. I would specifically like to thank Dr. Bernard Shanks and Dr. Douglas D. Alder for their guidance, counsel, and patience during the course of this research. My gratitude also to the USU librarians who guided me through the maze of government publications on this subject. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii LIST OF MAPS iii CHRONOLOGY . iv I. INTRODUCTION 1 Uniqueness Survival II. COMING OF THE WHITE MAN 5 Exploration Early Federal Control: Confusion Monument Status: More Confusion III. ESTABLISHMENT OF A NATIONAL PARK. 12 Impetus for a Park Wallgren's Bills Issues and Adversaries Compromise and Resolution IV. -

The Green-Wood Historic Fund Its Verdict in January 2010

WINTER 2010 ›› “Angels of Music” ›› Recent RestoRAtions ›› the ARtists PRoject ›› confedeRAte RAM AlbeMARle ›› ThE Green-Wood HisToric FuNd its verdict in January 2010. I urge you to visit our website (http://www.green-wood.com/angelofmusic) where you can see additional beautiful photographs of their miniature sculptures shown on the next page. Preserving history for future generations does not come without a price tag. We estimate that the total cost for The Gottschalk Project will exceed $150,000. While I am very pleased with the artistic aspects of this effort, we have a long way to go meet our fund-raising goals. By making a tax-deductible donation, you will contribute not only to this wonderful project, but to all our efforts to keep Green- Wood thriving as an important center of art and history. Here are some quick updates on a few other exciting WINTER ’10: Green-Wood projects: The Historic Fund’s art collection continues to grow in WElcomE scope and importance. We now own more than 100 original notes fRoM the geM pieces of art work by artists interred here. Among our new- est acquisitions are works by residents Thomas Hicks and As winter sets in, Green-Wood is alive with activity. From Thomas Doughty, as well as a second work by Samuel S. our historic preservation work to our ongoing trolley Carr, a painting of Green-Wood resident Louise Griswold. tours, and from our successful partnerships with local public schools to the continued expansion of our archive Our educational programs are thriving as well. I am collection, the year 2009 has been one to be proud of. -

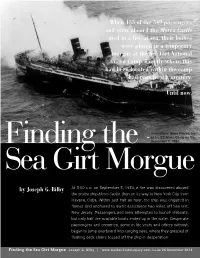

When 135 of the 549 Passengers and Crew Aboard the Morro Castle Died

When 135 of the 549 passengers and crew aboard the Morro Castle died in a fire at sea, their bodies were placed in a temporary morgue at the Sea Girt National Guard Camp. Exactly where this had been located within the camp had remained a mystery. Until now. International News Photos, Inc. of the SS Morro Castle on fire, September 8, 1934. by Joseph G. Bilby At 3:00 A.M. on September 8, 1934, a fire was discovered aboard the cruise ship Morro Castle, then on its way to New York City from Havana, Cuba. Within just half an hour, the ship was engulfed in flames and anchored to await assistance two miles off Sea Girt, New Jersey. Passengers and crew attempted to launch lifeboats, but only half the available boats ended up in the water. Desperate passengers and crewmen, some in life vests and others without, began to jump overboard into surging seas, where they grasped at floating deck chairs tossed off the ship in desperation. Finding the Sea Girt Morgue Joseph G. Bilby | www.GardenStateLegacy.com Issue 26 December 2014 New Jersey Governor A. Harry Moore was winding up the summer in the “governor’s cottage” at Sea Girt National Guard camp when he received news of the unfolding disaster. Also at the camp for its annual training was the African-American 1st Separate Battalion, New Jersey State Militia, which the Governor dispatched to the beach to help in rescue operations. Moore himself courageously flew off the camp parade ground in the observer seat of a National Guard airplane to mark survivors floating around the burning ship for rescue boats, which were on their way from Manasquan inlet. -

GOODSPEED MUSICALS STUDENT GUIDE to the THEATRE MICHAEL GENNARO Executive Director

GOODSPEED MUSICALS STUDENT GUIDE TO THE THEATRE MICHAEL GENNARO Executive Director MICHAEL P. PRICE Founding Director presents Music and Lyrics by COLE PORTER Original Book by GUY BOLTON & P.G. WODEHOUSE and HOWARD LINDSAY & RUSSEL CROUSE New Book by TIMOTHY CROUSE and JOHN WEIDMAN Scenic Design by Costume Design by Lighting Design by WILSON CHIN ILONA SOMOGYI BRIAN TOVAR Sound Design by Wig & Hair Design by Animals Trained by JAY HILTON MARK ADAM RAMPMEYER WILLIAM BERLONI Assistant Music Director Orchestrations by Production Manager WILLIAM J. THOMAS DAN DELANGE R. GLEN GRUSMARK Production Stage Manager Casting by Associate Producer BRADLEY G. SPACHMAN STUART HOWARD & PAUL HARDT BOB ALWINE Line Producer DONNA LYNN COOPER HILTON Music Direction by MICHAEL O'FLAHERTY Choreographed by KELLI BARCLAY Directed by DANIEL GOLDSTEIN APRIL 8 - JUNE 16, 2016 THE GOODSPEED TABLE OF CONTENTS Character Synopsis................................................................................................................................................................................4 Show Synopsis........................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writers: Cole Porter.............................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Writers.....................................................................................................................................................................................8 -

From Steamboat Inspection Service to US Coast Guard

From Steamboat Inspection Service to U.S. Coast Guard: Marine Safety in the United States from 1838‐1946 By PACS Barbara Voulgaris The American push westwards in the late 18th and early 19th centuries required increasing amounts of goods and services that only a new transport infrastructure could provide. As state and local governments and private companies funded road improvements and new road construction, this period came to be known as the ‘Transportation Revolution.’ Artist’s rendition of Robert Fulton’s steamboat Clermont. Commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Robert_Fulton. The transport of people and goods by animal power, however, proved slow and expensive. In 1797, Robert Fulton sent to President George Washington a copy of his “Treatise on Canal Navigation,” in which he suggested canal navigation between Philadelphia and Lake Erie. Fulton’s 1807 launching of the North River steamboat, more commonly known as Clermont, would have a dramatic affect on nearly every aspect of life in the new nation. It took Clermont 62 hours to steam from New York City to Albany, New York on its maiden voyage, in the process becoming the first commercially‐successful steamship built in the U.S. A local publication described the intense local reaction to the journey: The surprise and dismay excited among the crews of [other river] vessels by the appearance of the steamer was extreme. These simple people, the majority of whom had heard nothing of Fulton’s experiments, beheld what they supposed to be a huge monster, vomiting fire and smoke from its throat, lashing the water with its fins, and shaking the river with its roar, approaching rapidly in the very face of both wind and tide. -

Extensions of Remarks Section

June 20, 1996 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E1115 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS IN HONOR OF MRS. SALLIE rights cases, as well as pro bono services for ZACKY COLD STORAGE GROWTH LANGSETH FOR HER INDUCTION the NAACP. Hilbert is a noted trial lawyer and WARMS FRESNO ECONOMY INTO THE NATIONAL TEACHERS has had a distinguished career as a deputy HALL OF FAME, DEER PARK, TX prosecutor, corporation counsel, and interim HON. GEORGE P. RADANOVICH judge and mediator. OF CALIFORNIA HON. KEN BENTSEN In 1987, Hilbert founded the Indiana Coali- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF TEXAS tion for Black Judicial Officials, and he serves Wednesday, June 19, 1996 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES as the group's general chairman today. The Mr. RADANOVICH. Mr. Speaker, a major Wednesday, June 19, 1996 organization's purpose is to increase the num- ber of black judicial officials in the State of In- California poultry producer, Zacky Farms, is Mr. BENTSEN. Mr. Speaker, I rise to honor diana. The Indiana Coalition for Black Judicial embarking on an expansion plan in coopera- Mrs. Sallie Langseth of Pasadena, TX, who Officials organizes statewide public awareness tion with the city of Fresno, and I am pleased will be inducted into the National Teachers campaigns which have resulted in an in- to bring it to the attention of my colleagues. Hall of Fame in Emporia, KS, on June 22, creased number of black referees and judges Zacky Farms is an engine of economic en- 1996. She is one of five educators in the pro tem, the election of a black judge to the terprise in my 19th Congressional District. -

Fire Prevention History 2014

MOBILE FIRE-RESCUE DEPARTMENT Fire Code Administration Bureau of Fire Prevention Key events in history that significantly shaped today’s International Fire and Life Safety Codes The following information was captured from several websites including the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) January 1. First practical fire engine is tested, Cincinnati (OH), 1853 2. Meat processing plant fire kills 16, Terre Haute (IN), 1963 3. Marlborough Hotel fire kills 19, Minneapolis (MN), 1940 4. SS Atlantique passenger liner fire kills 18, English Channel, 1933 5. Texaco gas plant fire, loss worth $51 million, Erath (LA), 1985 6. Thomas Hotel fire kills 20 San Francisco (CA), 1961 7. Mercy Hospital fire kills 41, Davenport (IA), 1950 8. M/V Erling Jarl passenger ship fire kills 14, Bodo, Norway, 1958 9. Laurier Palace movie theater fire kills 78, Montreal (QB), 1927 10. Pathfinder Hotel fire kills 20, Fremont (NE), 1976 11. Fire damages 463 houses, Savannah (GA), 1820 12. Rhodes Opera House fire kills 170, Boyertown (PA), 1908 13. Coal mine fire kills 91, Wilburton (OK), 1926 14. USS Enterprise carrier fire kills 24, Pearl Harbor (HI), 1969 15. NFPA launches Fire Journal this month, 1965 16. McCormack Place hall fire, loss worth $289 million, Chicago (IL), 1967 17. SS Salem Maritime tanker fire kills 2, Lake Charles (LA), 1956 18. Sacred Heart College fire kills 46, St. Hyacinthe (PQ), 1938 19. Dance hall fire kills 31, Taipei, Taiwan, 1966 20. Phillips refinery fire, loss worth $78 million, Borger (TX), 1980 21. Nursing home fire kills 5, Maryville (TN), 2004 22. Gargantu bar fire kills 13, Montreal (QB), 1975 23. -

Every Man for Himself! Gender, Norms and Survival in Maritime Disasters

IFN Working Paper No. 913, 2012 Every Man for Himself! Gender, Norms and Survival in Maritime Disasters Mikael Elinder and Oscar Erixson Research Institute of Industrial Economics P.O. Box 55665 SE-102 15 Stockholm, Sweden [email protected] www.ifn.se Every man for himself! Gender, Norms and Survival in Maritime Disasters* Mikael Elinder, Oscar Erixson April 2, 2012 Abstract Since the sinking of the Titanic, there has been a widespread belief that the social norm of ‘women and children first’ gives women a survival advantage over men in maritime disasters, and that captains and crew give priority to passengers. We analyze a database of 18 maritime disasters spanning three centuries, covering the fate of over 15,000 individuals of more than 30 nationalities. Our results provide a new picture of maritime disasters. Women have a distinct survival disadvantage compared to men. Captains and crew survive at a significantly higher rate than passengers. We also find that the captain has the power to enforce normative behavior, that the gender gap in survival rates has declined, that women have a larger disadvantage in British shipwrecks, and that there seems to be no association between duration of a disaster and the impact of social norms. Taken together, our findings show that behavior in life-and-death situation is best captured by the expression ‘Every man for himself’. Key words: Social norms, Disaster, Women and children first, Mortality, High stakes JEL Codes: C70, D63, D81, J16 Mikael Elinder: Uppsala Center for Fiscal Studies, Department of Economics, Uppsala University and the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN), Stockholm Oscar Erixson: Uppsala Center for Fiscal Studies, Department of Economics, Uppsala University Corresponding author: Mikael Elinder, Department of Economics, Uppsala University, P.O.