325-452 Tourism 2019 04ENG.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dark Tourism

Dark Tourism: Understanding the Concept and Recognizing the Values Ramesh Raj Kunwar, PhD APF Command and Staff College, Nepal Email: [email protected] Neeru Karki Department of Conflict, Peace and Development Studies, TU Email: [email protected] „Man stands in his own shadow and wonders why it‟s dark‟ (Zen Proverb; in Stone, Hartmann, Seaton, Sharpley & White, 2018, preface). Abstract Dark tourism is a youngest subset of tourism, introduced only in 1990s. It is a multifaceted and diverse phenomenon. Dark tourism studies carried out in the Western countries succinctly portrays dark tourism as a study of history and heritage, tourism and tragedies. Dark tourism has been identified as niche or special interest tourism. This paper highlights how dark tourism has been theoretically conceptualized in previous studies. As an umbrella concept dark tourism includes than tourism, blackspot tourism, morbid tourism, disaster tourism, conflict tourism, dissonant heritage tourism and others. This paper examines how dark tourism as a distinct form of tourism came into existence in the tourism academia and how it could be understood as a separate subset of tourism in better way. Basically, this study focuses on deathscapes, repressed sadism, commercialization of grief, commoditization of death, dartainment, blackpackers, darsumers and deathseekers capitalism. This study generates curiosity among the readers and researchers to understand and explore the concepts and values of dark tourism in a better way. Keywords: Dark tourism, authenticity, supply and demand, emotion and experience Introduction Tourism is a complex phenomenon involving a wide range of people, increasingly seeking for new and unique experiences in order to satisfy the most diverse motives, reason why the world tourism landscape has been changing in the last decades (Seabra, Abrantes, & Karstenholz, 2014; in Fonseca, Seabra, & Silva, 2016, p. -

“Sustainable Tourism- a Tool for Development”

WORLD TOURISM DAY- 2017 “Sustainable Tourism- a Tool for Development” #TravelEnjoyRespect DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION -TEZPUR UNIVERSITY- UTTARAN- 2017 SPECIAL EDITION FOREWORD Dr. Papori Baruah, Professor and Head Department of Business Administration, Tezpur University I am greatly pleased that the students have come out with yet another edition of ‘Uttaran’ coinciding with the ‘World Tourism Day’. I congratulate the students and the faculty for this effort. The theme Sustainable Tourism is indeed very apt in present day context. We have seen several destinations in the world creating havoc to the environment and the artefacts by unplanned management of tourism activities. This has happened to the snow-capped mountains of the Himalayas to seaside destinations of Thailand. Hence, we must relook at our tourism strategies to conserve the pristine beauty of nature and preserve the heritage for future. We need to shift our focus from gaining mere economic benefit through exploitation of resources to sustainability. I am sure that the articles published in ‘Uttaran’ will at least try to usher some change in the mind-set of the readers. Best wishes. (Papori Baruah) Page 2 UTTARAN- 2017 SPECIAL EDITION CONTENTS 1) From the Editor’s Desk 4 2) UNWTO Official Message 5-6 3) Sustainable Tourism 7-8 4) Why Tourism should be Sustainable? 10-13 5) Involvement of Local Community for promotion of Eco- tourism. 14-19 6) Tourism and Ecosystem 20-21 7) Being a Traveller 23-24 8) Beholding the Dzukou Lily 26-28 9) Mysteries of North East 29-32 10) Peculiar forms of Tourism 33-35 11) Bicycle Tourism – Old Wine in New Bottle 36-37 12) Bhomoraguri Stone Inscription 39-41 13) Raasta.. -

Interim Policy for Prosecutors In

P.O. Box 17 Sender: P.O. Box 17, CH-8127 Forch 8127 Forch, Switzerland The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Committee Secretary, Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee PO Box 6100, Parliament House Canberra, ACT 2600 Australia Forch, 20 August 2014 Medical Services (Dying with Dignity) Exposure Draft Bill 2014 A Bill for an Act relating to the provision of medical services to assist terminally ill people to die with dignity, and for related purposes Submission by DIGNITAS - To live with dignity - To die with dignity, Forch, Switzerland as requested, submitted in electronic format, by email to [email protected] as an attached pdf Contents of this submission page 1) Introduction ……..………………………………………………………….. 1 2) The freedom to decide on time and manner of one’s own end from a European Human Rights perspective ……………………………… 4 3) The protection of life and the general problem of suicide …………………..8 4) Suicide prevention – experience of DIGNITAS …..……………….………... 10 5) General remarks on the proposed Medical Services (Dying with Dignity) Act 2014 …………………………………………………….14 6) Comments on specific aspects of the proposed Medical Services (Dying with Dignity) Act 2014 …………………………….……………... 18 7) Conclusion ………………………………………………………………… 27 Medical Services (Dying with Dignity) Exposure Draft Bill 2014 20 August 2014 Submission by DIGNITAS - To live with dignity - To die with dignity page 2 of 28 1) Introduction “The best thing which eternal law ever ordained was that it allowed us one en- trance into life, but many exits. Must I await the cruelty either of disease or of man, when I can depart through the midst of torture, and shake off my troubles? . -

Ethnic Variations in Suicide Method and Location: an Analysis of Decedent Data

Death Studies ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/udst20 Ethnic variations in suicide method and location: An analysis of decedent data Brandon Hoeflein , Lorna Chiu , Gabriel Corpus , Mego Lien , Michelle A. Jorden & Joyce Chu To cite this article: Brandon Hoeflein , Lorna Chiu , Gabriel Corpus , Mego Lien , Michelle A. Jorden & Joyce Chu (2020): Ethnic variations in suicide method and location: An analysis of decedent data, Death Studies, DOI: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1805820 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1805820 Published online: 13 Aug 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 73 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=udst20 DEATH STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1805820 REPORT Ethnic variations in suicide method and location: An analysis of decedent data Brandon Hoefleina , Lorna Chiua, Gabriel Corpusa, Mego Lienb, Michelle A. Jordenc, and Joyce Chua aPalo Alto University, Palo Alto, California, USA; bCounty of Santa Clara Behavioral Health Services Department, Suicide Prevention Program, San Jose, California, USA; cSanta Clara County Medical Examiner – Coroner, Santa Clara, California, USA ABSTRACT This study analyzed ethnic variations in suicide method and suicide location for 1,145 sui- cide deaths in a diverse California county. Hanging was the most common method of sui- cide death. Latino/a/x and Asian and Pacific Islander (API) decedents were more likely to suicide-by-hanging; White and African American decedents were more likely to suicide-by- firearms. API and African American decedents were less likely than White decedents to die- by-suicide at home. -

The Great Depression in Monmouth County: an Exhibition at the Monmouth County Library Headquarters 125 Symmes Drive Manalapan, New Jersey October 2009

The Great Depression in Monmouth County: An Exhibition at the Monmouth County Library Headquarters 125 Symmes Drive Manalapan, New Jersey October 2009 Organized by The Monmouth County Archives Gary D. Saretzky, Curator Eugene Osovitz, Preparer “Illdestined Morro Castle off Beach at Asbury Park,” Sept. 9, 1934 Monmouth County Archives, Acc. #2007-12 Gift of Fred Sisser Produced by the Monmouth County Archives 125 Symmes Drive Manalapan, NJ 07726 http://visitmonmouth.com/archives Acknowledgments The special month-long exhibit in the lobby of the Monmouth County Library, “The Great Depression in Monmouth County,” was curated by Gary D. Saretzky with exhibit preparation by Eugene Osovitz. Joya Anderson of the Archives staff produced digital prints of many of the exhibit items. The curved wall portion of the exhibit was mounted by the Monmouth County Art Department under the direction of Roberta Ohliger. Editorial assistance for the exhibition catalog was provided by Patrick Caiazzo. This exhibit was drawn from the collections of the Monmouth County Archives, several other repositories, and a private collector. The cooperation of the following individuals and organizations who lent or provided materials for the exhibition is gratefully acknowledged: Bette Epstein and Joanne Nestor, New Jersey State Archives; Ron Becker, Michael Joseph, and Caryn Radick, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University; George Hawley, Newark Public Library; Laura Poll, Monmouth County Historical Association; Art Anderson; and Wendy Nardi. Images of Jersey Homesteads in this exhibit were obtained from the American Memory website of the Library of Congress, a national treasure, and articles from the Red Bank Register were printed from the very useful online version on the website of the Middletown Township Public Library. -

Medical Tourism Bibliography

Selected Bibliography for Medical Tourism (The Most Comprehensive Bibliography on the subject on the web) (Last update 22 Mar 2010, n=212 references and counting!) Please note the attempt to post references that have free and easy access from Internet sources. Numerous studies are found in print material. Please email us at recgeog (at) gmail.com with web accessible documents and studies! Abhiyan, J. (2006). Globalisation and Health. Towards the National health Assembly II. Retrieved 22 Mar 09 from http://www.esocialsciences.com/data/articles/Document12512007440.470791.pdf Altman, S., D. Shactman, and E. Eliat. (2006). Could US Hospitals Go the Way of US Airlines? Health Affairs. 25(1):11-21. Retrieved 23 Mar 09 from http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/25/1/11. American Medical Association. (2008). New AMA Guidelines on Medical Tourism. Retrieved 11 May 2009 from http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2008/07/07/prse0707.htm Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield in Wisconsin. (2008). Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield Introduces International Medical Tourism Pilot Program. Medical Devices & Surgical Technology Week,466. Retrieved January 13, 2009, from ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Source database. (Document ID: 1597943281). Association Resource Centre, Inc. (2006). Spa, Health & Wellness Sector: foreign competitor profiles. Retrieved 2 Jan 2009 from http://www.corporate.canada.travel/docs/research_and_statistics/ product_knowledge/Spa_Health_Wellness_Sector_Foreign_Competitor_Profile_eng.pdf Alsever, J. (2006). Basking on the Beach, or maybe on the Operating Table. October 15, 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2007 from NYTimes.com Associated Press. (2007). Issues Poll. Retrieved 8 April 2008 from http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-12-28-issuespoll_N.htm ABC News/Washington Post Poll. -

Preventing Suicide in Public Places: a Practice Resource

Preventing suicides in public places A practice resource Preventing suicides in public places About Public Health England Public Health England exists to protect and improve the nation's health and wellbeing, and reduce health inequalities. It does this through world-class science, knowledge and intelligence, advocacy, partnerships and the delivery of specialist public health services. PHE is an operationally autonomous executive agency of the Department of Health. Public Health England Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG Tel: 020 7654 8000 www.gov.uk/phe Twitter: @PHE_uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/PublicHealthEngland Prepared by: Dr Christabel Owens, Rebecca Hardwick, Nigel Charles and Dr Graham Watkinson at the University of Exeter Medical School Supported by: Helen Garnham, public health manager – mental health © Crown copyright 2015 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit OGL or email [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to [email protected] Published November 2015 PHE publications gateway number: 2015497 2 Preventing suicides in public places Contents About Public Health England 2 Contents 3 Foreword 4 Executive summary 5 Introduction 7 Methodology 8 Part 1. Suicides in public places 10 Part 2. A step-by-step guide to identifying locations and taking action 14 Part 3. Interventions to prevent suicides in public places. Practical examples and evidence of effectiveness 24 Appendix 1. -

Of Death Tourism

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 33 Number 2 Winter 2011 Article 3 1-1-2011 A Call for International Regulation of the Thriving "Industry" of Death Tourism Alexander R. Safyan Loyola Law School, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alexander R. Safyan, A Call for International Regulation of the Thriving "Industry" of Death Tourism, 33 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 287 (2011). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol33/iss2/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CALL FOR INTERNATIONAL REGULATION OF THE THRIVING “INDUSTRY” OF DEATH TOURISM Alexander R. Safyan* I. INTRODUCTION On July 7, 2009, distinguished English conductor Sir Edward Downes traveled with his wife, Lady Joan, to Zurich, Switzerland.1 Three days later, the couple visited the assisted suicide clinic Dignitas, where workers provided them with a clear, liquid drink that would enable them to end their lives together.2 Sir Edward and Lady Joan drank the “cocktail of barbiturates,” lay next to each other holding hands, and died within minutes.3 Lady Joan was seventy-four years old, and in the final stages of terminal cancer; Sir Edward was eighty-five years old, and nearly blind and deaf.4 However, unlike his wife, Sir Edward was not terminally ill.5 This story sparked new controversy surrounding the practices of assisted suicide clinics such as Dignitas, which offer patients the ability to peacefully and painlessly end their lives. -

The De-Medicalisation of Assisted Death

THE DE-MEDICALISATION OF ASSISTED DYING: IS A LESS MEDICALISED MODEL THE WAY FORWARD? SUZANNE OST I. INTRODUCTION In this paper, I contend that there are current, notable examples of the de-medicalisation of assisted death. Although assisted dying has been most commonly presented within a medicalised framework - a framework revolving around medical concepts and terminology, illnesses and medical professionals - the notion of de-medicalisation is employed to suggest that there are emerging models of assisted dying in which some medical aspects assumed to be an integral part of the phenomenon are both challenged and diminished. Within the social and legal debate surrounding assisted death, the focus in recent times appears to have moved away from a medic’s involvement in a clinically assisted death to “suicide tourism” and particularly, the matter of relatives “assisting” by making travel arrangements and accompanying their loved ones to a country in which according to local law, they can receive assistance to die. Debbie Purdy’s ultimately successful legal action, swiftly followed by the publication of the DPP’s’ interim and final policies for cases of assisted suicide and the related public consultation,1 have ensured that the matter of relatives facilitating assisted Law School, Lancaster University. I am grateful to John Coggon for his valuable comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Thanks are also due to Marleen Eijkholt, who kindly provided a translation of the Dutch case discussed in section III. A), and to Hazel Biggs and the two reviewers for the Medical Law Review. Responsibility for any errors remains with the author. -

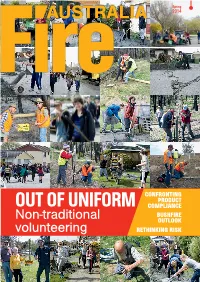

Out of Uniform Compliance Bushfire Non-Traditional Outlook Volunteering Rethinking Risk Advanced Automatic Fire Detection Systems

Spring 2014 confronting product out of uniform compLiance bushfire Non-traditional outLook volunteering rethinking risk Advanced Automatic Fire Detection Systems Leading Australian fire professionals choose PERTRONIC fire systems A network of Pertronic F120A fire alarm panels protects the occupants of Brisbane’s 81-storey Infinity Tower PERTRONIC INDUSTRIES PTY LTD Melbourne Sydney Brisbane Adelaide Perth PH 03 9562 7577 PH 02 9638 7655 PH 07 3255 2222 PH 08 8340 9533 PH 08 6555 3008 Fax 03 9562 8044 Fax 02 9638 7688 Fax 07 3054 1458 Fax 08 8340 9544 Fax 08 9248 3783 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2 | Fire AustrAliA spring 2014 www.pertronic.com.au 18 14 26 Spring 2014 Joint editors In thIs Issue Joseph Keller (FpA Australia) 14 Rethinking risk—empowering tel +61 3 8892 3131 communities adveRtIseR emAil [email protected] lIstIng 18 Product compliance—the 2 Pertronic nathan maddock (Bushfire and natural confronting reality 4 WBS Technology Hazards CrC) 22 Preventing fire and protecting 7 Archer Testing tel +61 3 9412 9605 9 CSR Bradford emAil [email protected] assets with oxygen-reduction systems 10 Lorient mandy Cant (AFAC) 1 3 Volvo tel +61 3 9419 2388 26 Higher than normal risk this fire 1 7 Australian Fire emAil [email protected] season Enterprises 2 1 Fire Australia 2015 28 Learning from adversity at key 25 FireSense Fire protection Association Australia industry conference (FpA Australia) ABn 30 005 366 576 -

Tourism Introduction • 1

TOURISM INTRODUCTION • 1. TOURIST – Is a temporary visitor staying for a period of at least 24 hours in the country visited and the purpose of whose journey can be classified under one of the following heads: • a) Leisure (recreation, holiday, health, study, religion and sport) b) Business, family, mission, meeting. – As per the WTO’s definition following persons are to be regarded as tourists: – i) Persons travelling for pleasure, for domestic reasons, for health etc. – ii) Persons travelling for meetings or in representative capacity of any kind (scientific, administrative, religious etc.) – iii) Persons travelling for business purposes. – iv) Persons arriving in the course of sea cruises, even when they stay for less than 24 hours (in respect of this category of persons the condition of usual place of residence is waived off. 2 • 2. EXCURSIONIST—is a temporary visitor staying for a period of less than 24hours in the country visited. (Including travellers on the cruises). • 3. TRAVELER or TRAVELLER - commonly refers to one who travels, especially to distant lands. 3 Visitor • As per WTO is that it does not talk about the Visits made within the country. • For these purposes a distinction is drawn between a Domestic and an International Visitor. • Domestic Visitor-A person who travels within the country he is residing in, outside the place of his usual environment for a period not exceeding 12 months. • International Visitor –A person who travels to a country other than the one in which he has his usual residence for a period not exceeding -

One Way Ticket-Route to Death: How Right Is to Promote As a Commercial Initiative?

DOI: 10.20491/isarder.2017.322 One Way Ticket-Route To Death: How Right Is To Promote As A Commercial Initiative? Arzu Kılıçlar Fulden Nuray Küçükergin1 Seval Kurt Gazi University, Faculty of Gazi University, Faculty of Gazi University, Faculty of Tourism, Department of Travel Tourism, Department of Travel Tourism, Department of Tourism Management and Tour Guiding, Management and Tour Guiding, Management, 06830 Golbasi, 06830 Golbasi, Ankara, Turkey 06830 Golbasi, Ankara, Turkey Ankara, Turkey orcid.org/0000-0002-3223-582X orcid.org/0000-0002-0943-0467 orcid.org/0000-0002-9012-5522 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Beyza Adıgüzel Bahadır İnanç Özkan Halil Can Aktuna Gazi University, Faculty of Gazi University Gazi University, Faculty of Tourism, Department of Tourism Social Sciences Institute Tourism, Department of Travel Management, 06830 Golbasi, 06500 Besevler - Ankara, Turkey Management and Tour Guiding, Ankara, Turkey orcid.org/0000-0002-7665-6765 06830 Golbasi, Ankara, Turkey orcid.org/0000-0002-2932-1671 [email protected] orcid.org/0000-0002-5930-2834 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract In this study, it has been argued the efforts of combining the concept of euthanasia and assisted suicide in the last few years with the concept of tourism. This study aims to investigate the concepts of euthanasia/assisted suicide with their medical, legal and religious dimensions and how right it is to promote the practicing centers as commercial tourism initiatives. Initially, tourism and tourist concepts have been explained then medical and juristically embodiments and applications have been detailed. It is pointed that, in many countries euthanasia and assisted suicide is forbidden while Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, United States of America, Canada and Colombia are the countries accepting euthanasia/assisted suicide.