56-58 Pine Street Building Designation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downtown Alliance Honors Seven Exceptional Leaders for Service to Lower Manhattan

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Nicole Kolinsky, (212) 835-2763, [email protected] Downtown Alliance Honors Seven Exceptional Leaders for Service to Lower Manhattan Exceptional Service Honorees, Left to Right: David Ng, Glen Guzi, Yume Kitasei, Seth Myers, Liz Berger, Sean Wilson, Thomas Moran, Dr. Robert Corrigan New York, N.Y. (November 29, 2012) - The Alliance for Downtown New York presented Exceptional Service Awards today to seven individuals who have helped make life better for residents, workers and visitors in Lower Manhattan. “These seven individuals have played a major role in helping in making Lower Manhattan a resilient, dynamic, 21st century neighborhood,” said Downtown Alliance President Elizabeth H. Berger at a breakfast at the Down Town Association. “In recent weeks, as Lower Manhattan faced significant challenges in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, these individuals once again displayed their tireless dedication to restoring Lower Manhattan to the world class neighborhood that it has become.” Thursday’s event was the 11th annual installment of the awards, given out by the Downtown Alliance, the city’s largest Business Improvement District. The event annually honors members of the public and private sectors who have worked to improve and advance Lower Manhattan. You can view photographs of the event at the Downtown Alliance’s Flickr page at http://www.flickr.com/photos/downtownny The honorees are: Sean Wilson, CB Richard Ellis. Wilson is a Senior Research Analyst responsible for leading rigorous and elaborate analyses to assess the Midtown South and Downtown office markets. He has routinely contributed timely information to the Downtown Alliance’s research and communications efforts, including industry- specific information about Lower Manhattan’s growing media industry. -

Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District Designation Report

Cover Photograph: Court Street looking south along Skyscraper Row towards Brooklyn City Hall, now Brooklyn Borough Hall (1845-48, Gamaliel King) and the Brooklyn Municipal Building (1923-26, McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin). Christopher D. Brazee, 2011 Borough Hall Skyscraper Historic District Designation Report Prepared by Christopher D. Brazee Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Jennifer L. Most Technical Assistance by Lauren Miller Commissioners Robert B. Tierney, Chair Pablo E. Vengoechea, Vice-Chair Frederick Bland Christopher Moore Diana Chapin Margery Perlmutter Michael Devonshire Elizabeth Ryan Joan Gerner Roberta Washington Michael Goldblum Kate Daly, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Sarah Carroll, Director of Preservation TABLE OF CONTENTS BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT MAP ................... FACING PAGE 1 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ................................................................................ 1 BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT BOUNDARIES ............................. 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BOROUGH HALL SKYSCRAPER HISTORIC DISTRICT ........................................................................................ 5 Early History and Development of Brooklyn‟s Civic Center ................................................... 5 Mid 19th Century Development -

Happy Birthday Hamilton! 2017 Presented by the Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society Monday, January 9Th – Jersey City and Lower Manhattan

Happy Birthday Hamilton! 2017 Presented by the Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society Monday, January 9th – Jersey City and Lower Manhattan New York and New Jersey, January 7-11, 2017 1 PM: “The Birth of Hamilton and Jersey City” Join Jersey City Mayor Fulop, Councilmember Boggiano, and author Thomas Fleming Alexander Hamilton was born on January 11, 1757 on the island of Nevis. at City Hall to learn about Alexander Hamilton's key role in founding Jersey City Happy Birthday Hamilton! is an annual program hosted during the anniversary of shortly before Hamilton passed away in 1804 Alexander Hamilton’s birthday. Through presentations, historic site visits, and other Location: City Hall, 280 Grove Street, Jersey City, NJ commemorative events, attendees can learn more about Hamilton’s fascinating life. 6:30 PM: Michael Newton: "Alexander Hamilton's Year of Birth: 1755 vs. 1757" We also partner with Hamilton’s birth island of Nevis in these festivities. In addition Author and National Hamilton Scholar Michael E. Newton explores the debate on to the Nevis Historical and Conservation Society’s annual Alexander Hamilton which year Hamilton was born, showing the existing evidence and which is stronger Birthday Tea Party on Nevis, this year the AHA Society will host a large delegation of Location: Fraunces Tavern Museum, 58 Pearl Street, NYC officials from Nevis attending the events in New York City and New Jersey, including Tickets: $10 (Museum members $5). Reservations required and seating is limited. the Premier of Nevis, the St. Kitts and Nevis Ambassador, and the NHCS President. Tuesday, January 10th – Lower Manhattan Program of Events Note: All events are open to the public and are free, unless ticket information is listed 12 PM: Stephen F. -

Forest Avenue and Stevens Avenue Portland, Maine Historic Context

Forest Avenue and Stevens Avenue Portland, Maine Historic Context Scott T. Hanson Sutherland Conservation & Consulting August 2015 General context Development of Colonial Falmouth European settlement of the area that became the city of Portland, Maine, began with English settlers establishing homes on the islands of Casco Bay and on the peninsula known as Casco Neck in the early seventeenth century. As in much of Maine, early settlers were attracted by abundant natural resources, specifically fish and trees. Also like other early settlement efforts, those at Casco Bay and Casco Neck were tenuous and fitful, as British and French conflicts in Europe extended across the Atlantic to New England and both the French and their Native American allies frequently sought to limit British territorial claims in the lands between Massachusetts and Canada. Permanent settlement did not come to the area until the early eighteenth century and complete security against attacks from French and Native forces did not come until the fall of Quebec to the British in 1759. Until this historic event opened the interior to settlement in a significant way, the town on Casco Neck, named Falmouth, was primarily focused on the sea with minimal contact with the interior. Falmouth developed as a compact village in the vicinity of present day India Street. As it expanded, it grew primar- ily to the west along what would become Fore, Middle, and Congress streets. A second village developed at Stroudwater, several miles up the Fore River. Roads to the interior were limited and used primarily to move logs to the coast for sawing or use as ship’s masts. -

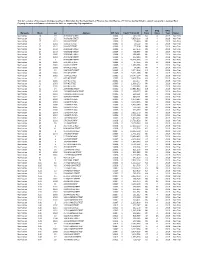

2019 Non Filers Manhattan

This list consists of income-producing properties in Manhattan that the Department of Finance has identified as of 7/1/20 as having failed to submit a properly completed Real Property Income and Expense statement for 2019 as required by City regulations. Tax Bldg. RPIE Borough Block Lot Address ZIP Code Final FY19/20 AV Class Class Year Status Manhattan 10 19 25 BRIDGE STREET 10004 $ 749,700 K2 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 11 15 70 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 4,859,100 O8 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 17 1213 50 WEST STREET 10006 $ 70,450 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 17 1214 50 WEST STREET 10006 $ 59,550 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 17 1215 50 WEST STREET 10006 $ 77,908 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 24 1168 40 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 627,373 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 24 1172 40 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 498,946 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 25 1002 25 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 386,480 RK 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 25 1003 25 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 532,444 RK 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 29 1 85 BROAD STREET 10004 $ 98,500,050 O4 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 29 1301 54 STONE STREET 10004 $ 47,366 R8 2C 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 33 1001 99 WALL STREET 10005 $ 1,059,455 RK 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 33 1003 99 WALL STREET 10005 $ 64,346 RK 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 37 13 129 FRONT STREET 10005 $ 3,574,800 H3 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 40 1001 73 PINE STREET 10005 $ 5,371,786 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 40 1002 72 WALL STREET 10005 $ 14,747,264 RB 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 41 15 60 PINE STREET 10005 $ 3,602,700 H5 4 2019 NonFiler Manhattan 41 1001 50 PINE STREET 10005 $ 233,177 -

January 18, 2019 Madison SB LLC C/O Minerva Management LLC Attn

Public Service Commission John B. Rhodes Chair and Chief Executive Officer Gregg C. Sayre Diane X. Burman James S. Alesi Commissioners Thomas Congdon Deputy Chair and Executive Deputy Three Empire State Plaza, Albany, NY 12223-1350 www.dps.ny.gov John J. Sipos Acting General Counsel Kathleen H. Burgess Secretary January 18, 2019 Madison SB LLC c/o Minerva Management LLC Attn: Roopa Bhusri 80 Harrow Lane Manhasset, NY 11030 Re: Matter 18-02433 – Petition of Verizon New York Inc. for Limited Orders Of Entry for 14 Multiple-Dwelling Unit Buildings in the City of New York. Dear Sir or Madam, On October 18, 2018 Verizon New York, Inc, (Verizon) filed a petition with the Public Service Commission requesting an order approving the right of limited entry to assess the building to establish an adequate installation plan (Public Service Law §228) for 77 Avenue D, Manhattan, New York. The petition states that the record owner of the building is Madison SB LLC and includes proof of service of a copy of the petition upon the landlord. It is necessary that the company gain access to the building in order to complete its installation review. It will use the information gained from this entry to develop an installation plan that it will present to the landlord in order to gain access to install its facilities. This plan, when adequately completed, will include reasonable conditions to protect the safety, functioning, appearance, aesthetics and integrity of the building. In the event that the landlord denies entry for installation after receiving the installation plan, Verizon would need to file a subsequent petition for Order of Entry to obtain access to the building; and the Commission would review the plan as part of its investigation of the petition, including consideration of your response. -

Reciprocal Clubs Around the Country and the World

Madison Club Reciprocity Madison Club members are entitled to reciprocal privileges with over 200 other private clubs when traveling domestically or abroad. Many clubs offer concierge service for local theatre events and also come equipped with meeting rooms, overnight accommodations and/or athletic facilities. The following is a complete listing of our reciprocal clubs around the country and the world. Please contact the reciprocal club directly for reservations and then call the Madison Club to request a card of introduction to be sent in preparation of your visit. SYMBOL KEY: (A) = OVERNIGHT ACCOMMODATIONS (F) = FITNESS FACILITY (G) = GOLF - CLUBS WITHIN THE UNITED STATES - Alabama University Club of Phoenix Los Angeles Athletic Club (A)(F) 39 East Monte Vista Road 431 West 7th Street The Club Phoenix, AZ 85004-1434 Los Angeles, CA 90014 1 Robert S. Smith Drive **must pay upon departure** Ph: 213-625-2211 Birmingham, AL 35209 Ph: 602-254-5408 Room Reservations: 800-421-8777 Ph: 205-323-5821 Fax: 602-254-6184 Fax: 213-689-1194 Fax: 205-326-8990 [email protected] [email protected] www.theclubinc.org www.universityclubphoenix.com www.laac.com Alaska Marines' Memorial Association (A)(F) California 609 Sutter Street Petroleum Club of Anchorage San Francisco, CA 94102 3301 C Street, Suite #120 Berkeley City Club (A)(F) Ph: 415-673-6672 Anchorage, AK 99503 2315 Durant Avenue Fitness Center: 415-441-3649 Ph: 907-563-5090 Berkeley, CA 94704 Fax: 415-441-3649 Fax: 907-563-3623 Ph: 510-848-7800 www.marineclub.com [email protected] Fax: 510-848-5900 www.petroclub.net [email protected] Petroleum Club of Bakersfield www.berkeleycityclub.com 5060 California Ave. -

Reciprocal Clubs Procedures for Using Reciprocal Clubs

Reciprocal Clubs Procedures for Using Reciprocal Clubs One of the privileges of the Columbia Club membership is our reciprocal arrangements with more than 200 private clubs throughout the U.S. and abroad. When visiting a reciprocal club, members must obtain a Letter of Introduction. These letters are issued to members in good standing only and may be obtained from the Membership Office, Monday through Friday from 9:00am to 5:00pm. The letter, which is issued in the member’s name for use by the member, is valid for the duration of your visit and is sent ahead of the member to the host club. A copy of the letter will be sent to the member for their records as well. Columbia Club members must conform to the rules, regulations and policies of the host club. It is advisable for members to call the reciprocal club prior to their visit for reservations, rules and any operational changes. Charges made by Columbia Club members at reciprocal clubs are to be settled upon departure. Additional information on your reciprocal clubs can be found on your website, www.columbia-club.org. To obtain a Letter of Introduction, call 317-761-7517, or email your membership coordinator at [email protected]. When contacting your membership coordinator, please have your name, member number and dates you will be visiting the club prepared. Contact individual clubs for hours of operation. For your convenience, your Indiana Reciprocal Clubs are listed below: The Anderson Country Club Maple Creek Golf & Country Club The Country Club of Terre Haute Pine Valley Country Club The Harrison Lake Country Club Pottawattomie Country Club Hickory Stick Golf Club The Sagamore Club Hillcrest Country Club Ulen Country Club For more information on these clubs, please refer to the Indiana club listings in the brochure. -

AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY BUILDING, 150 Nassau Street (Aka 144-152 Nassau Street and 2-6 Spruce Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 15, 1999, Designation List 306 LP-2038 AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY BUILDING, 150 Nassau Street (aka 144-152 Nassau Street and 2-6 Spruce Street), Manhattan. Built 1894-95; Robert Henderson Robertson, architect; William W. Crehore, engineering consultant; John Downey, Atlas Iron Construction Co., and Louis Weber Building Co., builders. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 100, Lot 3.1 On March 16, 1999, the Landmarks Presetvation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the American Tract Society Building (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. A representative of the building's owner stated that they were not opposed to designation. Three people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the New York Landmarks Consetvancy and the Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission received several letters in support of designation. Summary The American Tract Society Building, at the __. .. - ··· r -r1 southeast comer of Nassau and Spruce Streets, was . \ " Ll-1 constructed in 1894-95 to the design of architect R. H. _ _-r4 I 1! .li,IT! J . Robertson, who was known for his churches and institutional and office buildings in New York. It is one of the earliest, as well as one of the earliest extant, steel skeletal-frame skyscrapers in New York, partially of curtain-wall construction. This was also one of the city's tallest and largest skyscrapers upon its completion. Twenty full stories high (plus cellar, basement, and th.ree-story tower) and clad in rusticated gray Westerly granite, gray Haverstraw Roman brick, and buff-colored terra cotta, the building was constructed with a U-shaped plan, having an exterior light court. -

Hotel Inventory Q3 2020

Lower Manhattan Hotel Inventory October 2020 Source: Downtown Alliance Year Hotel Class/ Meeting Name Location Rooms Owner/ Developer Open Status Space (SF) Existing Hotels (South of Chambers Street): 1 Millennium Hilton New York Downtown 55 Church Street 569 1992 Upper Upscale ( 3,550) 2 New York Marriott Downtown 85 West Street 515 1994 Host Hotels & Resorts Upper Upscale ( 20,220) 3 Radisson Wall Street 52 William Street 289 1995 McSam Hotel Group Upper Upscale ( 5,451) 4 Wall Street Inn 9 South William Street 46 1999 Independent ( 580) 5 The Wagner Hotel at the Battery 2 West Street 298 2002 Highgate Luxury ( 12,956) 6 Conrad New York Downtown 102 North End Avenue 463 2004 Goldman Sachs Luxury ( 17,571) 7 Eurostars Wall Street Hotel 129 Front Street 54 2006 Independent ( - ) 8 Hampton Inn Manhattan-Seaport-Financial District 320 Pearl Street 65 2006 Metro One Hotel LLC Upper Midscale ( - ) 9 Gild Hall – a Thompson Hotel 15 Gold Street 130 2007 LaSalle Hotel Properties Luxury ( 4,675) 10 Holiday Inn New York City – Wall Street 51 Nassau Street 113 2008 Metro One Hotel LLC Upper Midscale ( - ) 11 AKA Tribeca 85 West Broadway 100 2009 Tribeca Associates Luxury ( 3,000) 12 Club Quarters, World Trade Center 140 Washington Street 252 2009 Masterworks Dev Upper Upscale ( 5,451) 13 Andaz Wall Street 75 Wall Street 253 2010 The Hakimian Organization Luxury ( 10,500) 14 Holiday Inn Express New York City – Wall Street 126 Water Street 112 2010 Hersha Hospitality Upper Midscale ( - ) 15 World Center Hotel 144 Washington Street 169 2010 Masterworks -

THURSDAY, APRIL 19 the Gender Fairness Committee, Supreme Court, New York County Appellate Division, First Department

THURSDAY, APRIL 19 The Gender Fairness Committee, Supreme Court, New York County Women’s History Month Celebration featuring a lecture by Susan Herman, Deputy Commissioner, Collaborative Policing, NYPD 1 p.m.-2 p.m. At 60 Centre Street, Room 300 Contact: Greg Testa 646-386-3617 Appellate Division, First Department (CLE) A Practical Guide to Understanding and Interrupting Implicit Bias Mirna Martinez Santiago 2 CLE credits 6 p.m.–8 p.m. New York County Supreme Court, 111 Centre Street Jury Room, 11th Floor. Contact: Amy Ostrau at 212-340-0558 or [email protected]. The Society of Professional Investigators Meeting: “Recent Developments in Fraud Hotlines: The Sexual Harassment Crisis” with Speaker Professor Chelsea Binns 6 p.m. Forlini’s 93 Baxter Street Contact C. E. Gordon at [email protected] or 516-433-5065 New York City Bar How to Be an Effective Ally: Practical Tips for Advocating Across Difference 6:30 p.m. – 8:30 p.m. 42 West 44th Street Register: www.nycbar.org Mindfulness & Well-Being in Law Committee Open House 7 p.m. - 8:30 p.m. 42 West 44th Street Register: www.nycbar.org New York City Bar (CLE) What a Relief! Practicing Before the NYC Board of Standards & Appeals 6 p.m.–9 p.m. 3 CLE Credits 42 West 44th Street Contact: Rosan Dacres 212-382-6630 [email protected] Practising Law Institute Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Update 9 a.m.–5 p.m. 1177 Avenue of the Americas www.pli.edu/TCJA18 Appellate Advocacy 1 p.m.–5 p.m. -

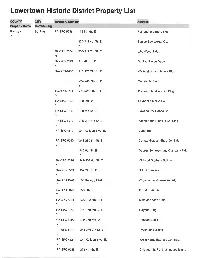

Lowertown Historic District Property List

Lowertown Historic District Property List COUNTY CITY Inventory Number Address Property Name Contributing Ramsey St. Paul RA-SPC-5246 176 5th St. E. Railroad and Bank Bldg. y 205-213 4th St. E. Samco Sportswear Co. y RA-SPC-5364 208-212 7th St. E. J.H. Weed Bldg. N RA-SPC-5225 214 4th St. E. St. Paul Union Depot y RA-SPC-7466 216-220 7th St. E. Walterstroff and Montz Bldg. y 224-240 7th St. E. Constants Block y RA-SPC-5271 227-231 6th St. E. Konantz Saddlery Co. Bldg. y RA-SPC-5248 230 5th St. E. Fairbanks-M orse Co. y RA-SPC-5249 230 5th St. E. Power's Dry Goods Co. y RA-SPC-5272 235-237 6th St. E. Koehler and Hinricks Co. Bldg. y RA-SPC-4519 241 Kellogg Blvd. E. Depot Bar N RA-SPC-5250 242-280 5th St. E. Conrad Gotzian Shoe Co. Bldg. y 245 6th St. E. George Sommers and Company Bldg. y RA-SPC-5226 249-253 4th St. E. Michaud Brothers Building y RA-SPC-5369 252 7th St. E. B & M Furniture y RA-SPC-4520 255 Kellogg Blvd. E. Weyerhauser-Denkman Bldg. y RA-SPC-5370 256 7th St. E. B & M Furniture y RA-SPC-5251 258-260 5th St. E. Mike and Vic's Cafe y RA-SPC-5252 261-279 5th St. E. Rayette Bldg. y RA-SPC-5227 262-270 4th St. E. Hackett Block y RA-SPC-5371 264-266 7th St. E. O'Connor Bu ilding y RA-SPC-4521 271 Kellogg Blvd.