Catalogue Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping an Arm's Length

MAPPING AN ARM’S LENGTH: Body, Space and the Performativity of Drawing Roohi Shafiq Ahmed A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales. 2013 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed …………………………………………….............. 28th March 2013 Date ……………………………………………................. ! DECLARATIONS Copyright Statement I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. -

Download Catalog

www.vaslart.org 20 Vasl Artists’ Collective16 VaslPakistan Ramla Fatima, 2016, To let, Taaza Tareen 8 Jamshed Memorial Hall, Karachi 20 Vasl16 www.vaslart.org [email protected] Vasl Working Group 2016 Adeela Suleman | Coordinator Naila Mahmood | Coordinator Hassan Mustafa | Manager Yasser Vayani | Assistant Manager Halima Sadia | Graphic Designer Hira Khan | Research Assistant Veera Rustomji | Assistant Coordinator Patras Willayat Javed | Support Staff Khurrum Shahzad | Support Staff Catalog Design Halima Sadia Copy Writing Veera Rustomji Photography Hassan Mustafa Mahwish Rizvi (Cord of Desires) Naila Mahmood Yasser Vayani Cover Image Hasan Raza (To let, Taaza Tareen 8) Supported by Triangle Network, UK www.trianglearts.org Getz Pharma, Pakistan www.getzpharma.com Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture. Pakistan www.indusvalley.edu.pk Karachi Theosophical Society All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©Vasl Artists’ Collective, 2017 Karachi, Pakistan Ehsan Memon, 2016 To let, Taaza Tareen 8, Peetal Gali, Karachi See View Single Artist Teaching Residency | Page 7 Suleman Aqeel Khilji, Lahore for Drawing Documents, IVS January 11 – February 29, 2016 To let Taaza Tareen 8 | Page 19 Ammara Jabbar, Karachi Ehsan Memon, Lahore Hasan Raza, Karachi Ramla Fatima, Rawalpindi in collaboration with Karachi Theosophical -

64 Pakistani Artists, 30 and Under

FRESH! 64 Pakistani Artists, 30 and Under Amin Gulgee Gallery Karachi March 2014 Curated by Raania Azam Khan Durrani Saba Iqbal Amin Gulgee Amin Gulgee Gallery Amin Gulgee launched the Amin Gulgee Gallery in the spring of 2002, was titled Uraan and in 2000 with an exhibition of his own sculpture, was co-curated by art historian and founding Open Studio III. The artist continues to display editor of NuktaArt Niilofur Farrukh and gallerist his work in the Gallery, but he also sees the Saira Irshad. A thoughtful, catalogued survey need to provide a space for large-scale and of current trends in Pakistani art, this was an thematic exhibitions of both Pakistani and exhibition of 100 paintings, sculptures and foreign artists. The Amin Gulgee Gallery is a ceramic pieces by 33 national artists. space open to new ideas and different points of view. Later that year, Amin Gulgee himself took up the curatorial baton with Dish Dhamaka, The Gallery’s second show took place in an exhibition of works by 22 Karachi-based January 2001. It represented the work created artists focusing on that ubiquitous symbol by 12 artists from Pakistan and 10 artists of globalization: the satellite dish. This show from abroad during a two-week workshop in highlighted the complexities, hopes, intrusions Baluchistan. The local artists came from all and sheer vexing power inherent in the over Pakistan; the foreign artists came from production and use of new technologies. countries as diverse as Nigeria, Holland, the US, China and Egypt. This was the inaugural In 2003, Amin Gulgee presented another major show of Vasl, an artist-led initiative that is part exhibition of his sculpture at the Gallery, titled of a network of workshops under the umbrella Charbagh: Open Studio IV. -

KARACHI BIENNALE CATALOGUE OCT 22 – NOV 5, 2017 KB17 Karachi Biennale Catalogue First Published in Pakistan in 2019 by KBT in Association with Markings Publishing

KB17 KARACHI BIENNALE CATALOGUE OCT 22 – NOV 5, 2017 KB17 Karachi Biennale Catalogue First published in Pakistan in 2019 by KBT in association with Markings Publishing KB17 Catalogue Committee Niilofur Farrukh, Chair John McCarry Amin Gulgee Aquila Ismail Catalogue Team Umme Hani Imani, Editor Rabia Saeed Akhtar, Assistant Editor Mahwish Rizvi, Design and Layouts Tuba Arshad, Cover Design Raisa Vayani, Coordination with Publishers Keith Pinto, Photo Editor Halima Sadia, KB17 Campaign Design and Guidelines (Eye-Element on Cover) Photography Credits Humayun Memon, Artists’ Works, Performances, and Venues Ali Khurshid, Artists’ Works and Performances Danish Khan, Artists’ Works and Events Jamal Ashiqain, Artists’ Works and Events Qamar Bana, Workshops and Venues Samra Zamir, Venues and Events ©All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval system - without written permission of Karachi Biennale Trust ISBN Printed by Le Topical [email protected] [email protected] www.markings.com.pk Claremont House FOREWORD Sitaron say agay jehan aur bhi hain Abhi Ishaq kay imtehan aur bhi hain Many new worlds lie beyond the stars And many more challenges for the passionate and the spirited Allama Iqbal Artists with insight and passion have always re- by the state, have begun to shrink and many imagined the world to inspire fresh beginnings with turning points in Pakistan’s art remain uncelebrated hope. Sadequain communicated through public as they are absent from the national cultural murals, Bashir Mirza furthered the discourse with discourse. -

Resume/Timeline – Johannes Christopher Gerard – Info

Resume/Timeline – Johannes Christopher Gerard – [email protected] / www.johannesgerard.com Video / Performance / Installation / Photography / Printmaking – Interdisciplinary Projects 2020 Despite the pandemic and all regulations, some important interdisciplinary and collaboration projects could take place. Aktionsraum 2 (Action space 2) with video works and two performances” Isolate” and “Äblösen (peel off)” with Tanja Wilking at Kunstverein Ebersberg, Ebersberg, Germany KODEKÜ - Collision of the Arts Project, Bischofswerda. Germany Making art visible in rural regions. Creation of two site-specific installations, plus a live performance in collaboration with cellist Ulrich Thiem 2019 In Mexico for the collaboration project conecta-no conecta, The Lab program, Mexico City. In collaboration with performance artists Fred Castro (MX), Fey Montalvo( MX) and Hanna Doucet (FR).Honorable Mention for White Cup, 1st NATIONAL COLLOQIUM OF PERFORMANCE AND GENDER, The Faculty of Fine Arts of the Autonomous University of Querétaro, Mexico. Takes part at 20 Int. Performing Arts Festival in Hannover, Germany. In January creating Reflection an interdisciplinary performance with includes Land-Art installation and observer participation in conjunction with the, Montanha Pico Festial, PEDERARTE, Pico Island, Azores, PT . Performance and Workshop for children with autism and children from the SOS Kinderdorf partly having no parents or coming from families with issues in conjunction with the Aré Performaing Arts Festival, Yerevan, Armenia 2018 Stay in Yerevan, Armenia. Creating the project Eriwan im März (Yerevan in March). Interdisciplinary and collaboration project about the city of Yerevan. The life performance part was developed with 5 students from the Theater and Cinematographic Institute, Yerevan. At the same time experiment with a shorter version workshop/performance Unfolding-Unwrapped .as part of German language classes at Goethe Institute in Yerevan. -

UNDERGRADUATE PROSPECTUS 2022 Copyright © Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, 2021 All Rights Reserved

UNDERGRADUATE PROSPECTUS 2022 Copyright © Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, 2021 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used in any manner without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. UNDERGRADUATE PROSPECTUS 2022 CONTENTS ABOUT IVS ADMISSIONS The Symbol 05 Basic Eligibility Criteria for Applications 27 IVS History and Mission 06 Online IVS Admissions Portfolio 27 Core Values 07 Interview 27 Vision 07 Merit List 28 Message from the Chair, BoG 09 Interdepartmental Transfer Policy 29 Message from the Dean 10 Financial Assistance and Scholarships 29 and Executive Director Fee Payment Procedure 32 Charter and HEC Compliance 11 Fee Refund Policy 34 The IVS Journey 12 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2022 36 IVS Outreach 14 Administrative Ofces 18 ACADEMIC PROGRAMMES Statutory Bodies 19 Foundation Year 39 IVSAA 21 Department of Architecture 44 STUDENT LIFE AT IVS Department of Interior Design 58 Ofce of Student Affairs 22 Department of Communication Design 69 Department of Textile Design Ofce of Student Counselling 22 89 Fashion Design Study Trips 23 105 Department of Fine Art Student Week 24 117 Liberal Arts Programme Student Council 24 130 Graduate Programme 146 THE IVS FACULTY 150 The degree itself is very interdisciplinary. I've been lucky to have understood and applied elements of different disciplines into my academic pursuit as an Interior Architect. My advice to incoming students would be to not doubt themselves while trying to learn from their mistakes; analyzing them in the most positive way possible. My fondest memories were staying late at IVS with my friends working on group projects, joking around, bonding and making lifelong friends. -

Drawing Form

Drawing Form to avail themselves of certain pointers or clues when looking at not only utilise an enormous variety of media in the execution of these works; but the formidable impression exists that literal their work and ideas, but similarly the subject matter they embrace understanding of the text will avail the reader little or nothing. has no borders, or frontiers. Their drawing becomes a liberated and The text exists almost as an additional cryptic layer of meaning liberating act, ideally suited to exploring any number of dimensions or understanding. These are, after all studies that, despite the of the human condition, and any number of aspects of the built or graphic nature and element of social and political reportage natural world around them and us. And yet, despite the complexity that we might perceive in the images, have meanings that are of these artists’ work, there is at its core something that is almost ultimately enigmatic or obscured. primeval in its expression. It is almost as if all art must start – in There is a profound sense of exploration - that is, the action of the artist’s mind – as some sort of drawing. The urgency of drawing travelling in or through the familiar, the unfamiliar, the different, – the ways in which it yields instant results – is something that and the unusual, in order to learn about it - that resonates has ensured the continued primacy of the act within the realm throughout this exhibition. In that regard, these artists are of art practice. Likewise, drawing remains a somewhat steadfast possessed of both purpose and ability. -

Yawar Abbas Zaidif.H.E.A H.No: 899 Street :22, Baharia Town Phase Lv, Rawalpindi

Yawar Abbas ZaidiF.H.E.A H.No: 899 Street :22, Baharia Town Phase lV, Rawalpindi. M: 0333-3327234, e-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY OF QUALIFICATIONS Creative Design Educator highly trained in a varied array of artistic mediums. Passion for Teaching and talent for infusing art appreciation, and promoting imagination and open- mindedness. Proven ability to generate a highly creative learning environment. Extend personal- ized guidance and provide positive encouragement to ensure that each learner thrives. Collabora- tive Educator, with strong communication and interpersonal skills, an ability to interact with cross-cultural teams, with the high degree of professionalism, discretion and problem resolution capabilities. Quick learner, Self-motivated, Result oriented person, with aim to make a Dierence in the Society through Teaching. EDUCATION KINGSTON UNIVERSITY, UK (www.kingston.ac.uk) 2010 Kingston University, UK, established in 1899, oering course through its seven faculties including Art, Design & Architecture, and ranked 30th in UK Universities. MA – Design with Learning & Teaching in Higher Education Concentration: .Curriculum Development and Evaluation of Practice in Higher Education .Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education .Developing Teaching Practice and Supporting Students in Higher Education .Design Pedagogy and Practice esis: Nature of Expressive Typography- A Pedagogical Resource for Design Educators and Students UNIVERSITY OF BOLTON, UK (www.bolton.ac.uk) 2001 e University of Bolton is ranked top in the north-west -

Part II: Unveiling the Unspoken

LZK-8 SOUTH ASIA Leena Z. Khan is an Institute Fellow studying the intersection of culture, cus- ICWA toms, law and women’s lives in Pakistan. Part II LETTERS Unveiling the Unspoken By Leena Z. Khan Since 1925 the Institute of Current World Affairs (the Crane- MARCH, 2002 Rogers Foundation) has provided North Nazimabad, Defence, Bath Island — Karachi, Pakistan long-term fellowships to enable outstanding young professionals After beginning my study on women artists in Karachi I soon realized that to live outside the United States one newsletter would not give the subject matter justice. It was a difficult choice selecting which women artists to write about. I came across a number of talented and write about international women artists in the city, many who are still struggling to make a name for them- areas and issues. An exempt selves and legitimize their career-choice to their families and peers. For this news- operating foundation endowed by letter I chose to write on two notable and seasoned Karachi-based artists belong- the late Charles R. Crane, the ing to the first generation of the country’s art institutions — Meher Afroz and Institute is also supported by Riffat Alvi. The work of both women is remarkable because they have an informed contributions from like-minded and strong vision of what the society in which they live in could be. Although individuals and foundations. visually their paintings are very different, these two women share much in com- mon; Both have earned approbation in art circles throughout Pakistan and abroad; their respective paintings can be interpreted as a commentary on the social and TRUSTEES cultural landscape of the country; both have strong convictions and can criticize Joseph Battat the society in which they live as well as embrace it; both artists are deeply spiri- Mary Lynne Bird tual and have an introspective relationship toward their faith; both women are in Steven Butler their late 50s and opted not to marry. -

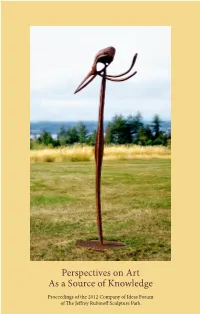

Perspectives on Art As a Source of Knowledge (2012 Forum

Perspectives on Art As a Source of Knowledge Proceedings of the 2012 Company of Ideas Forum of The Jeffrey Rubinoff Sculpture Park Published in Canada. All rights reserved. Contents To obtain reproduction permission please contact the publisher: Preface 4 Copyright © 2013 The Jeffrey Rubinoff Sculpture Park 2750 Shingle Spit Road, Hornby Island, British Columbia, Canada. 2012 Forum Topic: Art as a Source of Knowledge 11 www.rubinoffsculpturepark.org [email protected] 2012 Forum Participants 14 +1 250 335 2124 Dr. James Fox Other publications can be found at Introduction to the 2012 Forum 17 www.rubinoffsculpturepark.org/publications.php Dialogue on the Forum Introduction 30 Authors Dr. James Fox, Shahana Rajani, Jenni Pace Presnell, Shahana Rajani David Lawless, Jeremy Kessler and Jeffrey Rubinoff The Significance of the Relationship of Jeffrey Rubinoff’s Sculpture to its Environment 39 Editor Karun M Koernig Dialogue on Rajani presentation 44 Catalogue-in-Publication Data Jenni Pace Presnell Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication In Advance of Resignation Stated as Defiance 51 Company of Ideas Forum of the Jeffrey Rubinoff Sculpture Park (5th : 2012) Dialogue on Pace Presnell presentation 71 Perspectives on art as a source of knowledge : proceedings of the 2012 Company of Ideas Forum of the Jeffrey Rubinoff Sculpture Park / [editor, David Lawless Karun M. Koernig ; authors, James Fox ... et al.]. On the Evolutionary Origin of Artistic Development in the Chauvet Cave Paintings 84 Includes bibliographical references. Dialogue on Lawless presentation 96 ISBN 978-0-9917154-0-4 Jeremy Kessler The Search for a Nuclear Conscience 104 1. Art and society--Congresses. -

Vasl Online Newsletter #20 Feb-May 2011

Opportunities News Artists Galleries & Exhibitions Art Resources & Links Issue No. 20, February - May‘11 Newsletter Online www.vaslart.org Editorial Greetings colleagues and friends! With new collaborators joining Vasl, and the group extending its activities across Pakistan, the pace and scope of our activi- ties quickens and extends. As ‘The Rising Tide’ exhibition at The Mohatta Palace Museum approaches its closing weeks, the title of this exhibition takes on changing resonances. Across the Arab world, history-challenging events have been taking place, with many of our colleagues in the arts among those joining protests against repressive regimes in North Africa and the Middle East. Among them are Cairo-based Lara Baladi and Mohamed Abdelkarim, who both took part in the 2010 Vasl International Residency. Regretfully, Egyp- tian contemporary artist and teacher Ahmed Basiouny was among those tragi- cally killed during the protests in Cairo – protests that have bought monumen- tal changes to politics in Egypt and across the world. Adeel uz Zafar The manner in which protest movements have skipped from one terrain to from illustration work, (1998-2009) another across the Middle East, is testament to the power of strong networks led by personal meetings, cross-media communications and fraternal collabo- rations. In February, Vasl has hosted a ‘Knowledge and Skills Exchange’ resi- Artist In Focus Adeel Uz Zafar dency from Iranian artist Tooraj Khamenehzadeh. Tooraj is a coordinator of the This issue of the Vasl newsletter is the first to include a GS: Could you talk more about how working as an illustra- Rybon Art Centre in Tehran, (also part of the Triangle Network). -

Quddus Mirza 2018 ARTNOW PAKISTAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

THE ART NEWSPAPER MARCH 2018 www.artnowpakistan.com SECOND EDITION PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY UZAIR AZIZ | https://www.uzairazizphotography. The Lahore Biennale’s opening weekend program commences March 16 to 19 2018, and includes performances, guided tours of art works and venues, as well as collateral gallery programming within the city. Exhibitions and events for LB01 will be held at seven major venues that engage with the city’s Mughal, Colonial and Modern layers. The inaugural biennale recognizes the city in relation to its region, as reflected in the presentation of artists selected, and in the Biennale’s core and collateral programming. LB01 understands inclusivity, collaboration, and public-engagement as being central to its vision. LB01 has invited artists, groups, and institutions to work on various scales and at multifaceted sites. Editorial Note Editorial Note Fawzia Naqvi Quddus Mirza 2018 ARTNOW PAKISTAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLICATION DESIGN COURTESY JOVITA ALVARES Editor in Chief Editor It gives me immense pleasure to welcome you to the 2nd edition ‘In the beginning was the Word’, and one feels in the end it of the ArtNow Art Paper, which brings selected articles from will also be the Word; although in between it has assumed the online magazine into print. The current milieu of re- various forms: from handwritten manuscripts to Guttenberg gional and global art is abuzz with activity, with art fairs and prints, and to Kindle. From ink on paper to digital letters on biennales initiating and returning one after the other. The Lahore Biennale adds to this luminous screen. From a bound volume to an online publication.